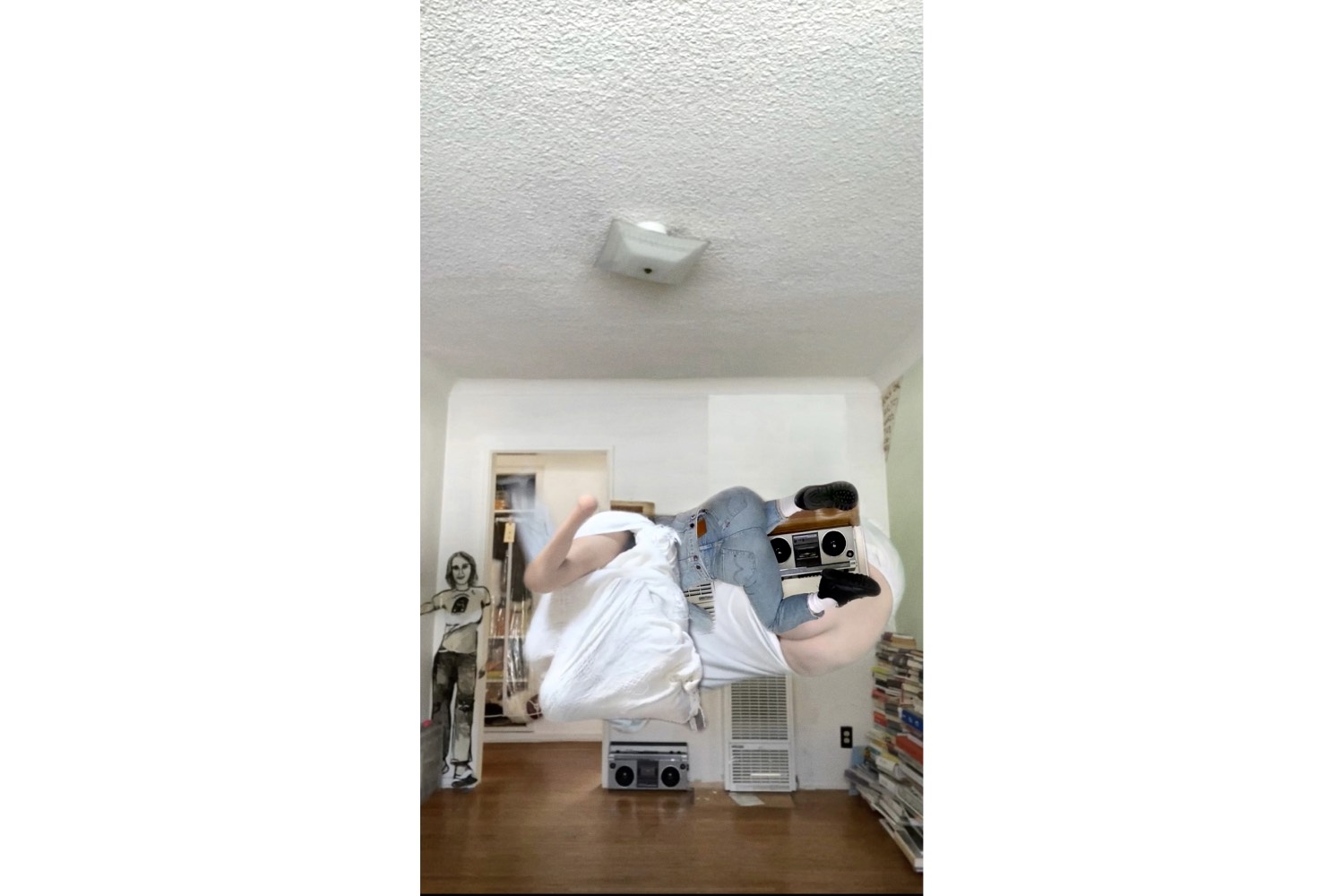

Miranda July’s creativity explodes in all directions: she’s perhaps best known as a filmmaker and a writer, but she has been making conceptual art and performance work for decades. “For me, it was less about becoming something than finding a way to sculpt a life that allows for all of the things that feed me in different ways,” she tells me over Zoom from her home studio in Los Angeles. It’s a space that’s already familiar to me — as well as to her 250,000 other Instagram followers — as the backdrop to her freestyle dance videos and now also as the setting for her latest project, F.A.M.I.L.Y (Falling Apart Meanwhile I Love You) (2024), for which she digitally “transported” seven strangers into the space to create a series of surreal performances that explore intimacy and the boundaries of self. Typifying July’s daring and democratic approach to making art, the project was initiated by an open call on Instagram and is included in “New Society,” her first major retrospective, now on view at Osservatorio Fondazione Prada in Milan. The show brings together all the facets of her practice, from her earliest performances in punk clubs to her collaborative projects and feature films.

Millie Walton: Tell me about F.A.M.I.L.Y. What was the starting point for the work?

Miranda July: I had a few different ideas that fell under the title F.A.M.I.L.Y, and only the final version was realized. I worked hard trying to figure out the right way to make something porous – something where other people could fit into me, essentially. I think the feeling was: what we expect or hope from social media and from family is to be so lovingly looked at that we would be okay. I wanted to create a visual of what would it look like to have that kind of sex. Is it more like taking something into your body, as if back into your womb? Is it mirroring? In every video I have made so far — using clunky TikTok tools and then very high-end sound — there is this sort of surreal orgy with me and a stranger or several strangers in my studio. I would say to these strangers, “You can isolate parts of your body with a sheet. You don’t always have to be a human form. I don’t want you to have to be representative of your gender, race, or age.” And with that came a language of abstraction.

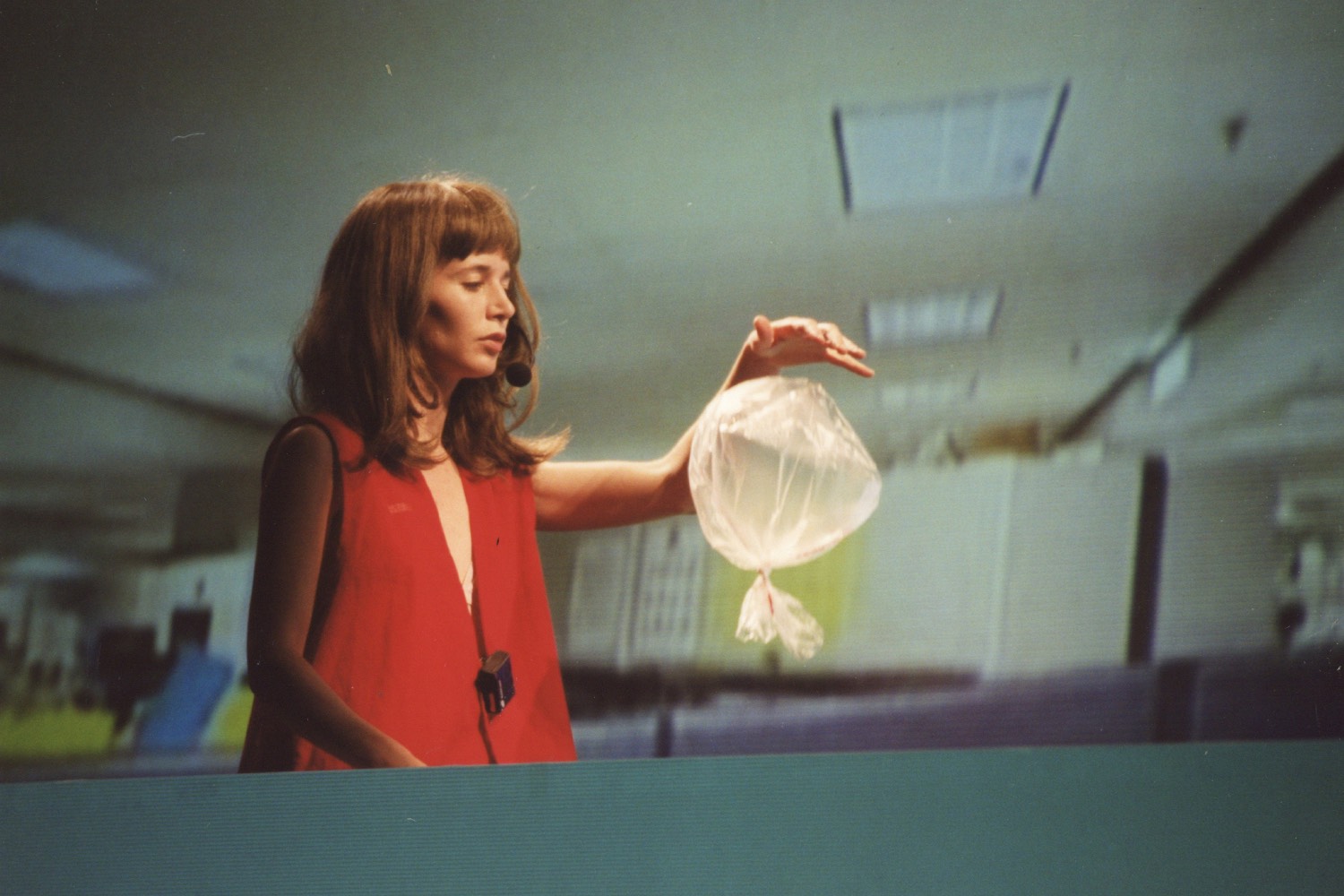

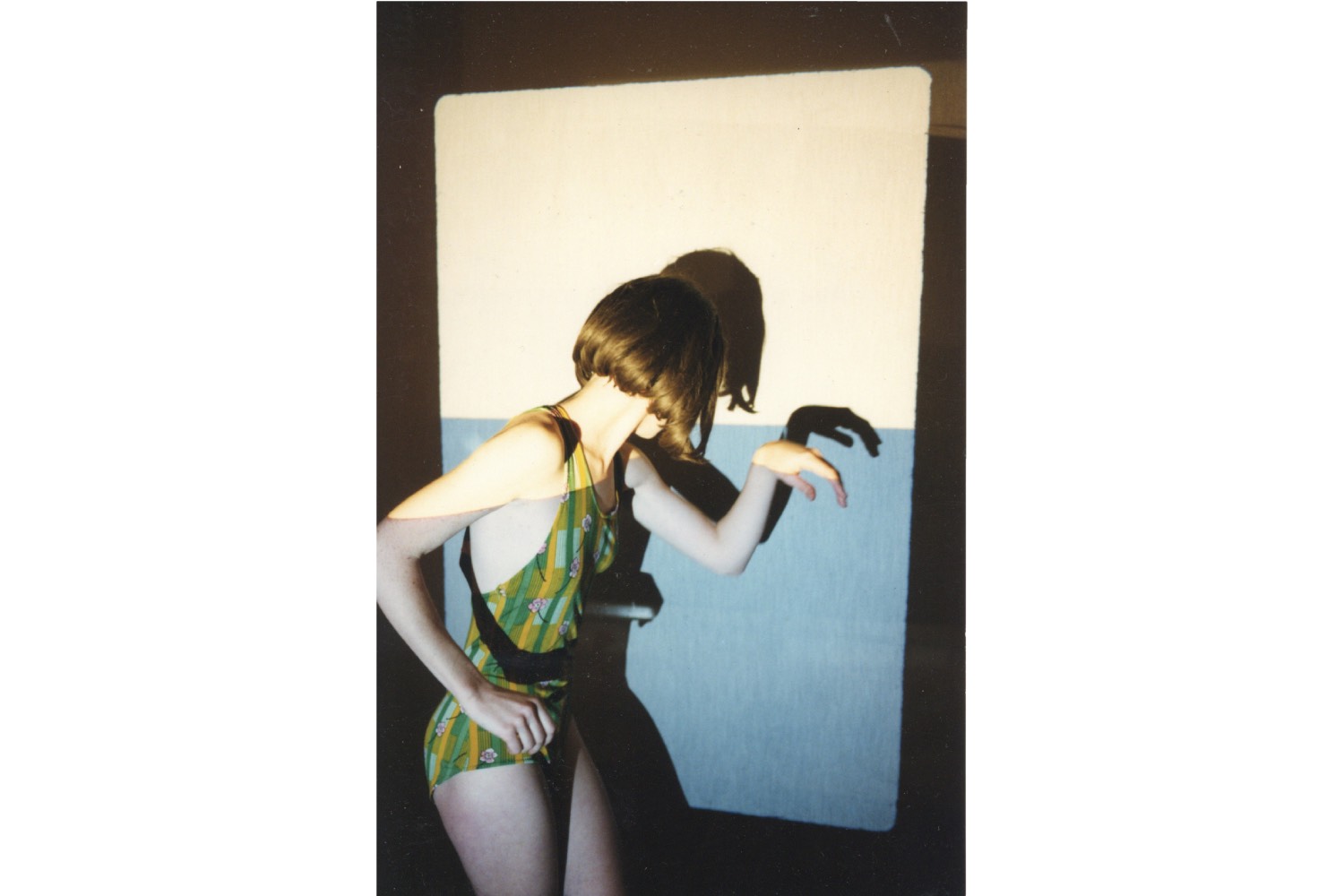

MW: Many of your older works also involved audience participation. I’m thinking about Things We Don’t Understand and Definitely Are Not Going to Talk About (2006), The Crowd (2004), or New Society (2015). What do you think draws you to those kinds of interactions? Is it the unpredictability? The risk?

MJ: It’s mysterious to me because on the one hand, like any writer-director, I am super into control. I have an internal world that I could hang out in forever. And yet, life doesn’t make sense to me unless there’s a sense of freedom that is real. Freedom includes things that are genuinely not in control or not completely in control. I’m always looking for that edge where the whole piece won’t capsize. It could, but I’m counting on a sort of collective agreement. After my first feature film came out, I realized that I had kind of destroyed one aspect of the performance work, which is the surprise element. But instead of bemoaning the fact that people were coming to see the girl from the movie, with Things We Don’t Understand (2006) — my first performance after the feature — I thought, “Well, if they’re coming with that kind of funny energy that you have when you’re seeing someone in the flesh who you saw on the big screen, maybe that will allow me as a performer to ask for some things that really make it clear that we’re in the present moment and that this moment will never happen again.” That’s what the audience participation is about in a way: to show that this specific group of people is making this performance, which won’t happen again. That’s what sets it apart from my film work. A film audience really does just sit there.

MW: And what about the gallery audience? How does that fit into your practice?

MJ: To be honest, because of the ephemeral nature of so much of my work that falls in the art category, I haven’t had much experience of that white-walls space and the art audience moving through it. The times that I have, at the Whitney Biennial and the Venice Biennale, I got a very different kind of response. For someone who is used to applause, it was like falling into nothingness. But with those shows, which were all group shows, there was no contextualization for me or who I was, whereas the retrospective at Osservatorio is all context. It has a curator, Mia Locks, who thought very hard about how to contextualize the works, so I have to set it apart from past experiences. I had no expectations that this would be quite so wonderful. I only got to visit the gallery two times before I left Milan, but seeing people really stand or sit in front of the videos and seeing them laughing or just taking it all in is incredibly satisfying.

MW: What you’re saying makes me think about the role or idea of an amateur, which is present in quite a few of your works. As a self-taught artist, have you been made to feel like an amateur in certain spaces?

MJ: I am so lucky because of my creative freedom. I wake up every day loving what I get to do, and often working in multiple mediums throughout the day. I made that happen. There was no life that I could copy that was just like what I wanted, so that’s what I worked for. But there is a kind of outsider feeling to it because each world thinks you’re more the other thing: “Oh, she’s not really a filmmaker, she’s an artist, or she’s a writer.” And the funny thing is that “artist” is the thing that people in the other worlds often default to. It’s something so vague that other industries figure that it must be the answer. That said, the invitations that I have had in the art world have been wonderful. I was just thinking about the project I did for Artangel in London in 2017 — the charity shop. That was one of the best experiences of my life. It’s very rare that any of this work is reviewed, but this project was. At the end of one of these reviews, the writer asked the question: But is it art? I remember thinking that that wasn’t the first store that has existed as a conceptual art piece; I was following a tradition, but because of who I am, because of my other work and probably to some degree because I’m a woman, that question still exists in relation to a lot of what I do. Luckily, whether the work is seen that way is not my only measurement of its success. There were people who went to that project every day – I think perhaps that’s also something that works against me: this very democratic relationship to the audience, going out of my way to make it more available rather than less.

MW: Has having your work curated by someone else made you think differently about it?

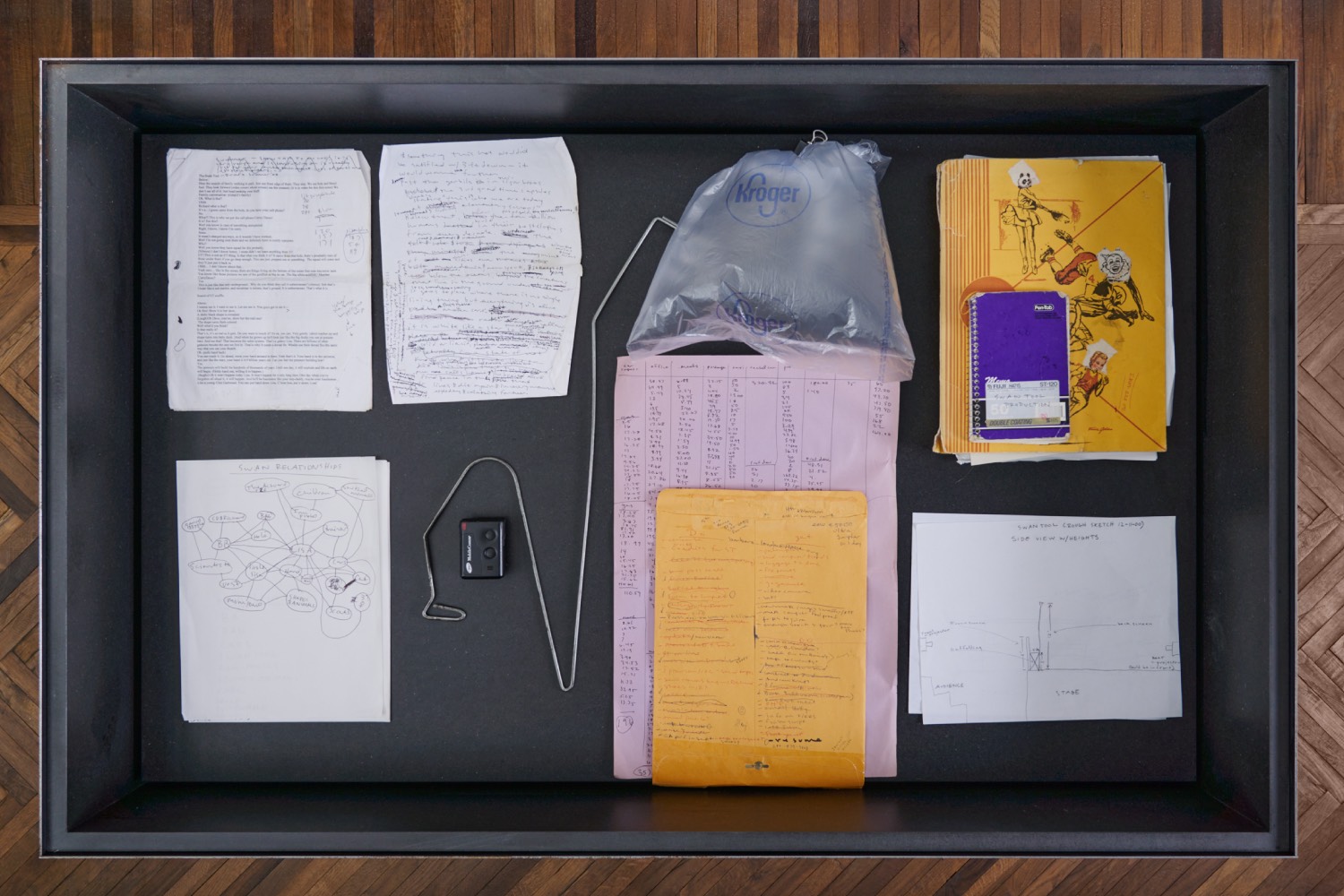

MJ: Yes, in ways that I’m still processing and will be for a while. There are all of these archival materials — ephemera, costumes, and props — which were all from performances that are a big part of the show. I started keeping this archive in my early twenties. I once saw an exhibition, I think it was of David Wojnarowicz, and I remember realizing: what is saved is remembered, and what is remembered becomes history, and history shapes our understanding of reality. The archives of almost any marginalized person in history would be interesting and would change our sense of reality. At this point, I was a young punk performer who nobody was asking to save the archives of, but I decided to do it anyway. It was like a radical act, a punk act. I would just save everything and that was the end game, so much so that this show was already well underway, everything had already been mapped out when it suddenly occurred to me to ask Mia whether she’d like to look in this room full of boxes. I asked her whether she thought any of it should be included and she just went very quiet and said, “Yes, absolutely.” That’s just one instance of having an internal process become clear because there’s someone from the outside looking in.