To question what language is — or what can be done with language, or to language — is a non sequitur for the purposes of discussing the work of American artist, critic, curator, and editor Aria Dean. It is futile to dwell on apparent negations or tautologies, or to directly question the unrhetorical artist, who freely admits to seeking something “impossible” in material and text.

While for the most part, the circulation of Dean — the literal movement of her work, Dean seen online, and Dean herself — is contained somewhat within Northern America and Europe, “Wolves” is a compendious show of sculpture, moving image, sound, and, in essence, writing. The exhibition opened at Progetto in Lecce, a small, Baroque town in the center of the peninsular heel of Italy during the last days of the heatwave Cerberus, which had choked out the Mediterranean for weeks. On the invitation of Boston-native artist Jamie Sneider — an artist herself who opened Progetto as a platform and temporary residence for artists invited to enter into a dialogue with the distinct landscape and architecture of Puglia — Dean spent a month living and producing in the exhibition space, which occupies a series of four connecting rooms wrapped around the small, sunlight-funneling central courtyard of a fifteenth-century palazzo. “Wolves” unfolds here, following a distinctly interrupted four-part pattern — a likely nod to the artist’s preceding interest in the stage as a presentational medium and making variations on the play as a vehicle for language. The three phrases of “Wolves” — the eponymous film, a series of iron sculptures, and the installation Mare (all 2023) — proceed, discretely and sardonically, to toe around liberal humanism, the politics of speech and sight, and a critique of the human effort to exert control over animals.

Dean’s exploration of the malleability and materiality of subjecthood continues most recently with a series of 3D-printed silicone sculptures designed through a comprehensive process that uses Unreal Engine tools to distort, compress, and manipulate forms fed into it. Deriving its essence from minimalist pioneer Robert Morris’s Box with the Sound of Its Own Making (1961), a nine-by-nine-inch wooden cube which emits the hammering and sawing sounds produced during its own creation, FIGURE A, Friesen Mare (2023) depicts the form of an oversized toy horse, albeit one recently passed through a trash compactor. Dean claims that “minimalism evades the representational sphere almost entirely”; thus, the figure or object of the preternaturally destroyed horse becomes an associative figure, a proxy. Mare (2023) — produced using the characteristically soft local Leccese limestone and carved by a local fabricator (who warned that his chisel might leave faint groove lines in the surface of the stone, much to Dean’s approval) — introduces this new, off-site body of work on familiar terms. Atop a reclaimed wooden pallet and sheets of Styrofoam, a heavy medallion of pietra leccese lies, its surface etched to show the smushed hooves, muzzle, body, legs, and mane of yet another ill-fated pony. “She told the program to liquefy the scan of the toy, then throw it against a wall,” Sneider explained to me. Dean’s decision to evade anachronism, modulating the appearance of previous sculptures in this series, yields a work well suited to its position; placed just off center from the motif at the center of the mosaic covering the floor, the sculpture is surreptitiously lit with dappled light that falls through a crack in the shutters. When I attended the opening of this exhibition in mid-July, the work, still soaked with water from carving, possessed, quite literally, a heavier materiality. The darker tone of the stone allowed shadows to appear more saturated on the roiling but unbroken surface of the flattened animal. However, when I returned to Lecce at the end of the month, and the stone had dried out, short slivers of fossils and other imperfections could easily be seen poking out of the dehydrated skin of the rock, which now seemed to glow in the sun. Mare demonstrates an homage. Dean asks: What if you liquified a horse, threw it against a wall, then had it made in Puglia?

The abstractive text accompanying this exhibition begins: “She lay on the floor and-not-quite [sic] cried thinking about how all productive processes are conscripted toward the production of the image of production.” It is unimaginable that the conditions of production wouldn’t be in the foreground of Dean’s mind. In the following, anxiety-ridden paragraph, the uncredited writer expresses hesitance “ to imbue these mute objects with something […] a patina of significance.” A list of things that “were real” includes “Love. Money. Iron. Stone. Her. The floor. Him. The animals. The sun, probably. This place, certainly.” Among other things not real: “Art, maybe. Pain, maybe. This place, certainly.” But the narrator assures us: “The only stable presences on the farm were the animals. If not the animals, the relation between them.” The stabilization of the prose marks the transition between Acts 1 and 2. In the smaller intermediary room, a five-part group of iron bells are hung around head height, flanking the doorways and the right side of the un-shuttered courtyard-facing window. Titled after a series of chewed-up words (poulet opal; pooled; LUPO; loop loop loop; and Lei lopes opaque, all 2023), the bells are conveniently without ringers, rendering their purpose as a herding apparatus void. Without bells, a shepherd wouldn’t know where his flock is when it escapes his line of sight. The undulating clanging helps keeps predators away, too, and is also said to keep the animals calm. Nonetheless, a rigorous, a priori carceral logic informs these objects and the artworks modelled thereafter; the notion that a motion-sounding collar charm is provided for safety’s sake rather than in the interests of ensuring continued ownership, particularly as they are installed here like trophies, is morally muddy.

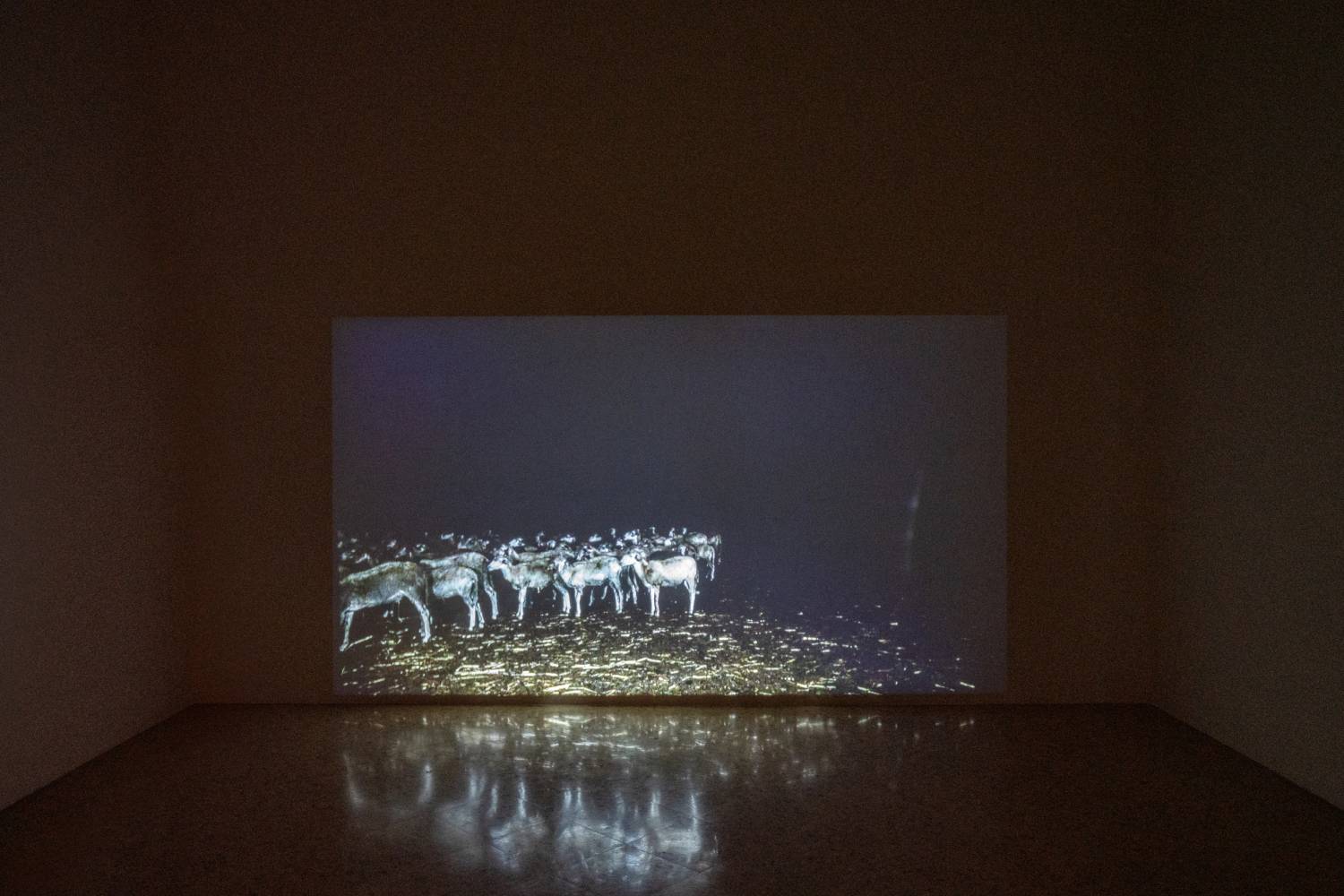

While regarding the group of heavy iron bells, produced at a foundry in Squinzano, north of Lecce, one might pick out the rhythmic ringing of bells, pealing amid some twanging strings and a low synth hum. A dog barks, then stops. The soundtrack to Wolves, the new film from which this presentation takes its name, was composed in collaboration with musician Laszlo Horvath, who accompanied Dean during this trip and production phase. Faintly echoing in the high-ceilinged rooms, the layered track carries far beyond the fourth room where the speakers are relegated. The shutters are drawn in the uncharacteristically empty (or characteristically, depending on whether one dares to qualify such a blatant act of refusal in plain terms) third room, which one must pass through to come closer to the source of the sound. The doorway that usually connects rooms three and four, where Wolves is installed, is politely blockaded with a black iron gate, Il recinto (2023), which restricts visual access to the screen. The simple vertical bar design of the gate, also produced at Squinzano, is complicated by the inclusion of four S-shaped swirls spread over parallel bars, creating a motif not dissimilar to the American dollar sign. A view of the work is double obstructed by the imposition of a projector mounted on a stand and festooned with cables. Directly facing the screen, the projector appears to be placed in the position of the camera used to shoot the work on site at a sheep farm and cheesemaker, also in the local area. The looping, twenty-five-minute film comprises darkness and sound followed by a single impromptu take. (The artist can be heard faintly whispering behind the camera, “That’s good!”) Lit with one spot, a herd of sheep nestle among each other on the left-hand side of the frame. They flinch when the sturdy Labrador manning their flock belts commands; when the dog moves to bark at the camera, one paw raised, they shuffle behind him; even when he sits, he barks.

Allegedly, the population of wolves in Puglia doubled during the pandemic, Sneider told me. The inferences contained in this anecdotal notion — also that the sheep are milked when they’re fed, or they’re fed when they’re milked, a tautology containing separately complicated implications — provides an unspoken depth to Dean’s work, which in this iteration, questions how agency is involved in human-animal relationships, and transfers between implied subject positions.