“HOWL,” the current exhibition of prophetic multimedia works by Doug Atkins, accelerates through Galerie Eva Presenhuber’s Maag Areal campus with a rapid succession of recurrent and shifting motifs (specifically environmental photography, geometric abstraction, and forms of address) that culminate in a confrontation of moving image and sound. The abject temporality of the various works functions contra the expectations of an oversaturated media culture. Moreover, this effect challenges viewers to accept a humanist approach toward a moral and philosophical critique of environmental politics: Aitken’s secularism inadvertently perversifies the antithetical position of simultaneously opposing and condoning oil extraction that “we” currently find ourselves in.

Introducing the exhibition is REEARTH (Underwater topography of the Earth) (2023), a large, wall-mounted sculpture depicting the planet’s land and water via a protracted version of the ubiquitous Mercator projection. Made with cast eco-resin and recycled plastic collected on Californian beaches, natural dyes color the incompletely explored sea floor, which is rugged and scarred. Whereas the surfaces of the continents are stark white and bleak, rippling tectonic fault lines, trenches, and chains of undersea mountains create concentrations in the orange-colored material. Following this are a number of acrylic and aluminum light boxes, each featuring a single word in block capitals: DRAMA 2 (2021); CONTACT (2023); HOWL (2023); and UNREAL (2023). Contrary to the map that appears against a white wall, these works are mounted against wallpapers containing imagery that causes a preternatural tension: inside the letters of HOWL, for example, mirrored and cropped images of orange rock formations, indicative of the dry, arid plains of Eureka, California, are enveloped by a verdant thicket of palm fronds.

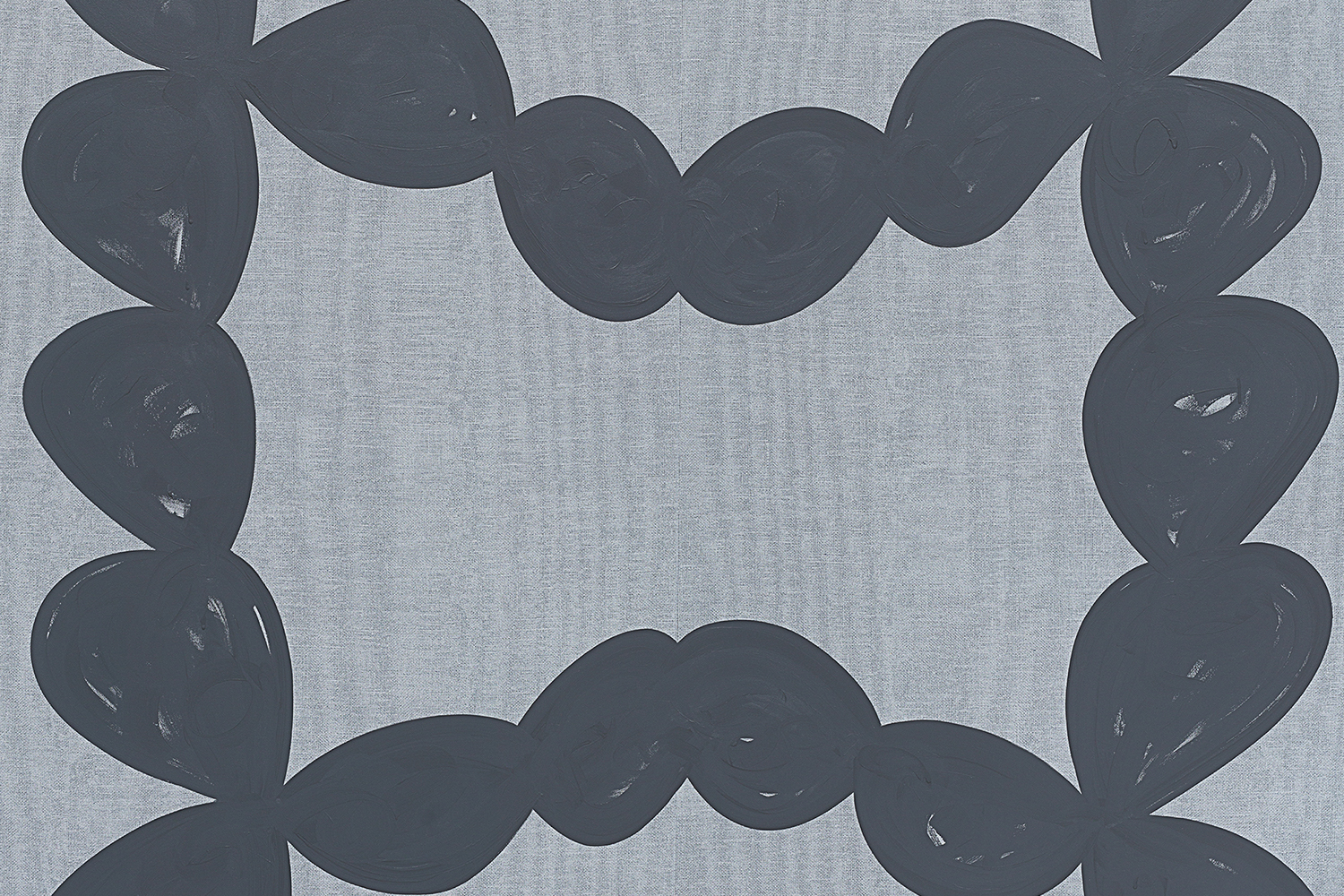

Thus far, the instructive and didactic capacity of the work is politely delivered through Aitken’s image-associational subversions, which encourage reflections on the contradictions of the planet. The idea that the progression toward environmental catastrophe is implicitly man-made is not driven home until one enters the second room of the exhibition space. Here, a bright, neutral-toned palette is emphasized through the juxtaposition of further wallpapering, which here shows a receding landscape of rocky and arid scrubland that peels away on one side to reveal patches of trompe l’oeil brickwork. Across three distinct sculptural groups, Aitken explores methods of geometric abstraction as well as the use of reflective surfaces to disorienting ends. The lightboxes Endless Oceans (2) and Endless Oceans (3) (both 2023) appear as triple overlapping bullseyes. The concentric rings making up each circle are divided into segments and filled with images such as bird’s-eye perspectives above container ships and unattributed, dry landscapes, among other unidentifiable views, suggesting the disintegration of natural order amid the promotion of capitalism. This form is appropriated for 3 Circles (2023), which uses polished stainless steel as its surface material, creating an elegant disruption to viewing, an effect which is dialled higher in the Terra (2023) series — three roundels, concave platters of wood mounted also with polished stainless steel surfaces that fling reflections of their surroundings around with impunity.

The kaleidoscopic tendencies of the preceding works cannot fully prepare the viewer for the experience of the eponymous multimedia installation at the core of this presentation, centered around a film that errs on the side of a condensed, documentary short, rather than an abstract “artist film.” This is not in spite of the totalizing surround sound (the work is accompanied by a looping, rhythmic techno soundtrack that becomes like an inevitability) and multichannel installation, which in fact helps collapse proximities between the staunch figures of narrator and narratee. The story is set in an undisclosed town in rural California, an area with which Aitken is intimately bonded, where fatigueless oil derricks swig from under the ground, and the town around it shutters gradually. Residents — via first-person voice-over or long, side-shot interviews — lament the situation, though not without nostalgia. “It’s an oil town … it’s a working town.” The offhanded phrase suggests a tautology of late capitalism: the bringer of wealth squanders its surroundings like a dying sun.