Marguerite Humeau’s exhibition at White Cube Bermondsey is structured as a journey, incorporating sound, moving image and sculpture and enlisting the collaboration of artificial intelligence as well as hives of skilled craftspeople in order to explore ideas of interdependence and collective intelligence. Leading us from the present and local to a distant, speculative future, Humeau entwines plural narratives around these themes – from a human society in collapse, to a simulation of the secret life inside an insect community, and a projected future gathering of a newly-formed collective in the process of synchronising.

The artist was inspired by eusocial insects such as ants, termites and bees, whose complex cooperative societies enable them to build huge structures and to cultivate other organisms in symbiotic relationships. Reflecting on the ants shepherding their aphids and the termites tending their fungus gardens, Humeau found an equivalent in the place yeast has assumed in human societies, as the essential ingredient of bread and beer around which our human collective has gathered. Contemplating the probability of our imminent, self- inflicted extinction as a species, Humeau sees insect societies as both the inheritors of our ravaged environment, and a prompt to consider how interdependence and cooperation might offer a means to avert our fate. ‘There are forms of life that will survive us’ she says; ‘how can we take them as our guides or companions to understand how to navigate our own futures?’.

Opening the exhibition in the 9x9x9 gallery, a collection of ceramic panels takes flight across the wall, offering fragmentary views of a crumbling city without human inhabitants. In 1965 the Polish artist Adam Kossowski was invited to realise a large mosaic for the Peckham Civic Centre, not far from White Cube’s Bermondsey gallery in London, called ‘The History of the Old Kent Road’. The former civic centre and its Grade-II listed mural are now scheduled for demolition: a human community dismantled, the collective under threat. Enlisting the help of an AI programme, Humeau sought a ‘collaboration’ with Kossowski, who had died in the year of her birth, in order to update his mural. The programme, GPT3, is trained on the online accumulation of our collective knowledge to simulate human speech and respond to questions in a learned persona. Using the prompts from this mediumistic interface with Kossowski’s resurrected intelligence, Humeau sketched a post-apocalyptic city. A small detail in the original mural shows a Camberwell Beauty butterfly, a rare and solitary migratory visitor to South London. In the vision of the future offered by the new mural they have multiplied into a swarm, apparently flourishing in a world hostile to human life. Not unlike the work of termites building the massive earthwork of their mound, the ceramic was created painstakingly by hand from Humeau’s line drawing, the toil of dozens of workers building to a large scale through tiny accretions.

From this overture set in the very near past and future, and in the intensely local South London environment with its mills and breweries, the opera that Humeau is orchestrating moves to less familiar places. A newly- constructed corridor in the gallery leads into darkness, towards a film showing termites engaged in some complex choreography, the black and white image sitting strangely between spirit photography, early cinema and scientific illustration. Its title, ‘Collective Effervescence’ refers to a concept described by social scientist Emile Durkheim in his 1912 volume Elementary Forms of Religious Life. According to Durkheim, ‘collective effervescence’ occurs when a society comes together with a common thought, to participate in a communal action. This moment of excitement serves to cohere the group, and thus the beliefs and rituals of religion have a social origin and purpose. Humeau again turned to an AI to generate images which speculate on early dancing rituals arising in termite society around their symbiotic fungi gardens.

Emerging at an unfamiliar point into the largest gallery, we arrive at a dim space resonant with sound: this could be the heart of the hive or a forest glade, in which a group of totems – perhaps queens or goddesses – is gathered. These primitive figures are alien and unexpected, yet suggest textures and forms familiar from nature: the gills of a mushroom, honeycomb and branching coral.

They are assembled from component parts of adobe, bronze, natural beeswax, handblown glass, and wood eaten by fungi and worms, and we sense that they may have just come together, and perhaps could recombine in other ways. Natural states of flux and change are implied not only by forms which ripple and flow, but in the suggestion of growth by replication and division, and by the impression that one part might be generating and nourishing another, as fungus flourishes from rotting wood. A sensuous materiality creates connective threads through the show, as the yellow glazed bricks of the mural are here picked up in the warm yellow beeswax and amber glass. The tactile, inviting surfaces are rich with incident created by woodgrain and pigments that seep and bloom like mildew. The exhibition is in one sense a celebration of human craft and industry, of a mastery of diverse materials by an industrious collective. It reveals at the same time how close sculptural process sits to the language of nature, whether building in layers of wax that accumulate like rings of tree growth, or casting from a mould as when splitting the husks of a chestnut to reveal the smooth, perfectly-fitting conker.

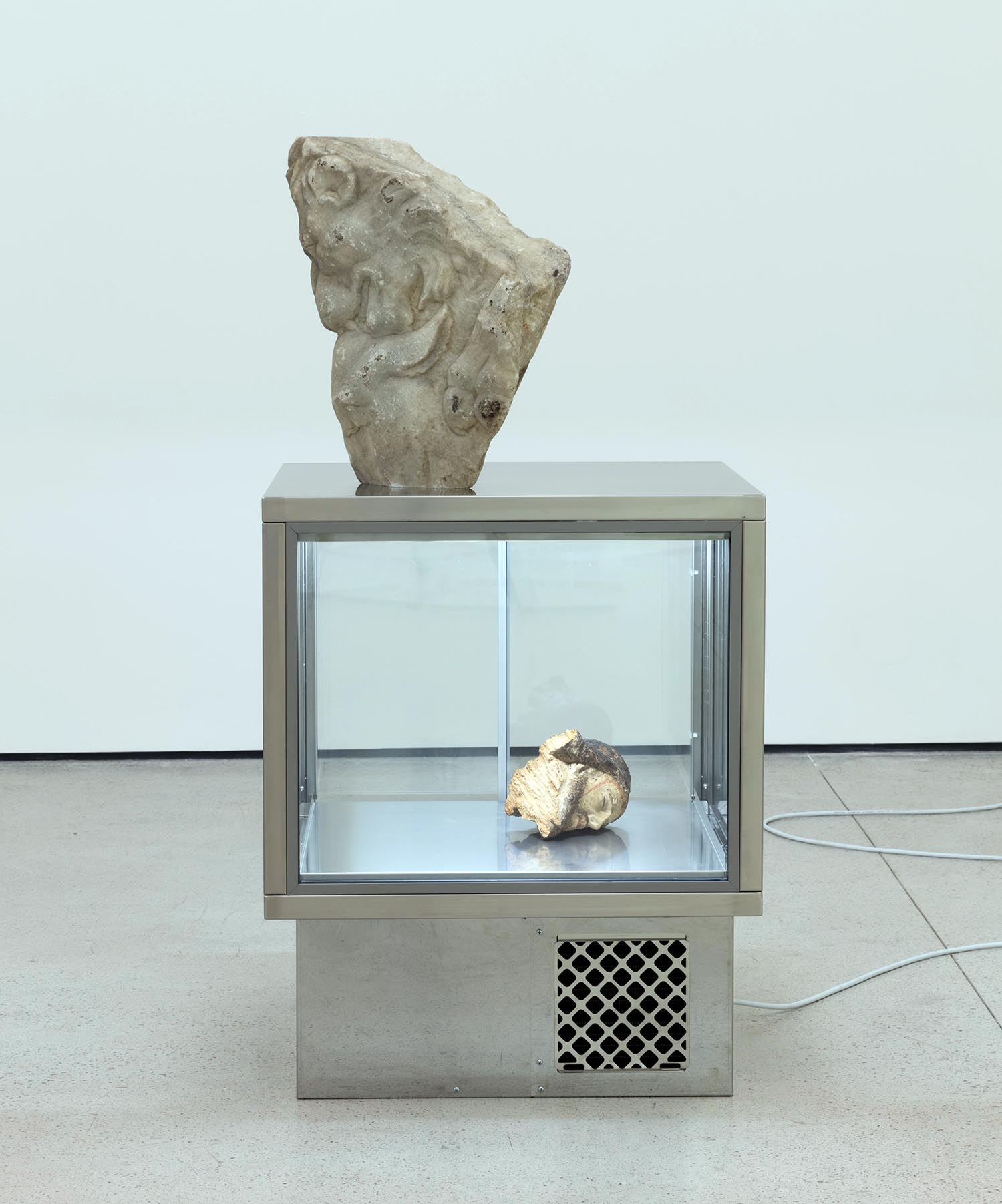

A number of the ‘Guardians’, as they are titled, offer up or encircle blown glass vessels inside which, almost like holy relics, are tiny quantities of beer, honey, 4500-year- old yeast, new yeast, wasp venom, and termitomyces (the termites’ fungus). If this is a ritual gathering, we might anticipate a mixing of these potent substances to create some elixir for the collective. The Guardians also have voices: the sounds they make, breathy, resonant or percussive, are all recorded from a single saxophone manipulated by experimental musician Bendik Giske.

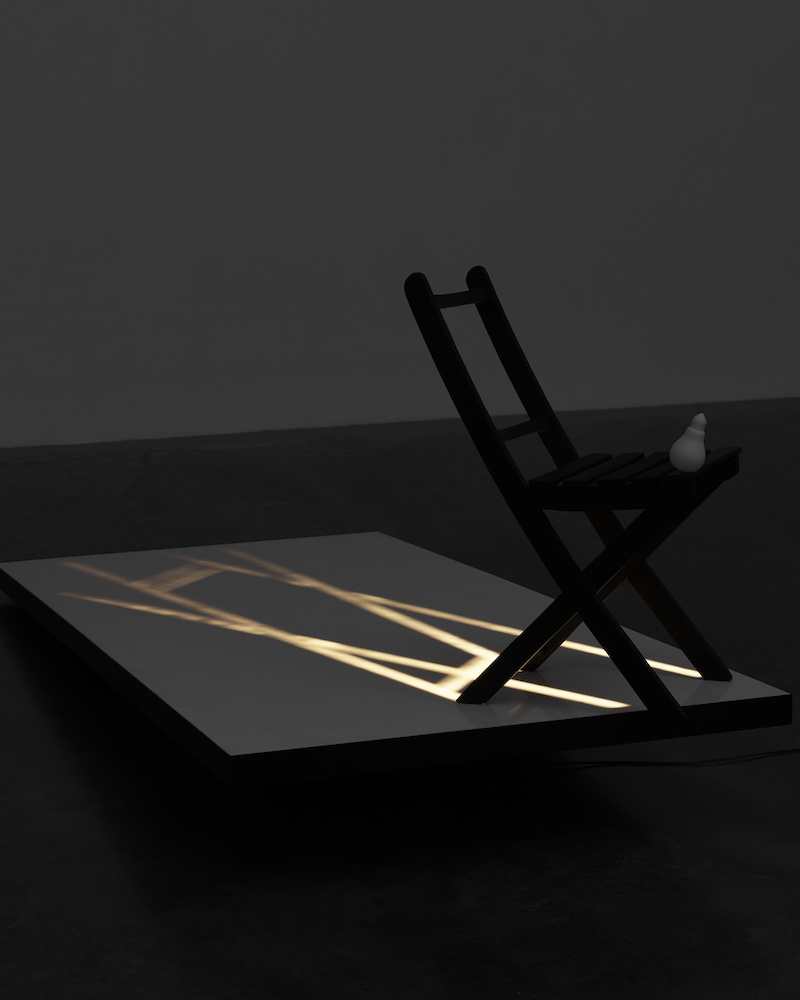

Like an orchestra tuning up, the individual sounds are anticipatory and unresolved, each on a separate repeated loop of different lengths, creating an ever-changing layering of sound that seems to be reaching for synchronisation, progressing towards harmony. The final element of the exhibition is a series of curved, rocking sculptures made from specially selected wood that is spalted, meaning patterned with the traces of fungal infection, or burled, a wood grain formed in response to a trauma; both distinctive traces which are evidence of the power of regeneration. These function as an interface that allows the visitor to participate in this collective happening, invited to recline and join in a state of disequilibrium and striving for balance.

“Meys” is a root word in Proto-Indo-European, the reconstructed common language of a hypothetical prehistoric population of Eurasia, meaning to change, to ferment, to mix or bring together. Together with its homophone, ‘maze’, the word describes the intention and structure of the exhibition, while creating a linguistic connection between the activities of Humeau’s eusocial subjects and early human societies. Increasingly, the discoveries of science impel us to comprehend the interconnectedness of life not only on a mystical but on a physical level, as understanding of our own microbiome, and of the mycorrhizal networks connecting all living plants and fungi, requires us to redefine notions of consciousness and intelligence and explodes the idea of the individual. Material substance offers a connection to understanding, and so to Humeau the biological is spiritual, in that it pertains to understanding the essence of life. Harnessing collective creative energy into the creation of this multi-sensory environment and its strange-yet-familiar proto-goddesses, the artist sets out to construct new mythologies: stories, archetypes and models that might help make sense of our world and offer patterns for living. Her preoccupation is no less that the meaning of life: how it emerges, how it evolves, if it has purpose.