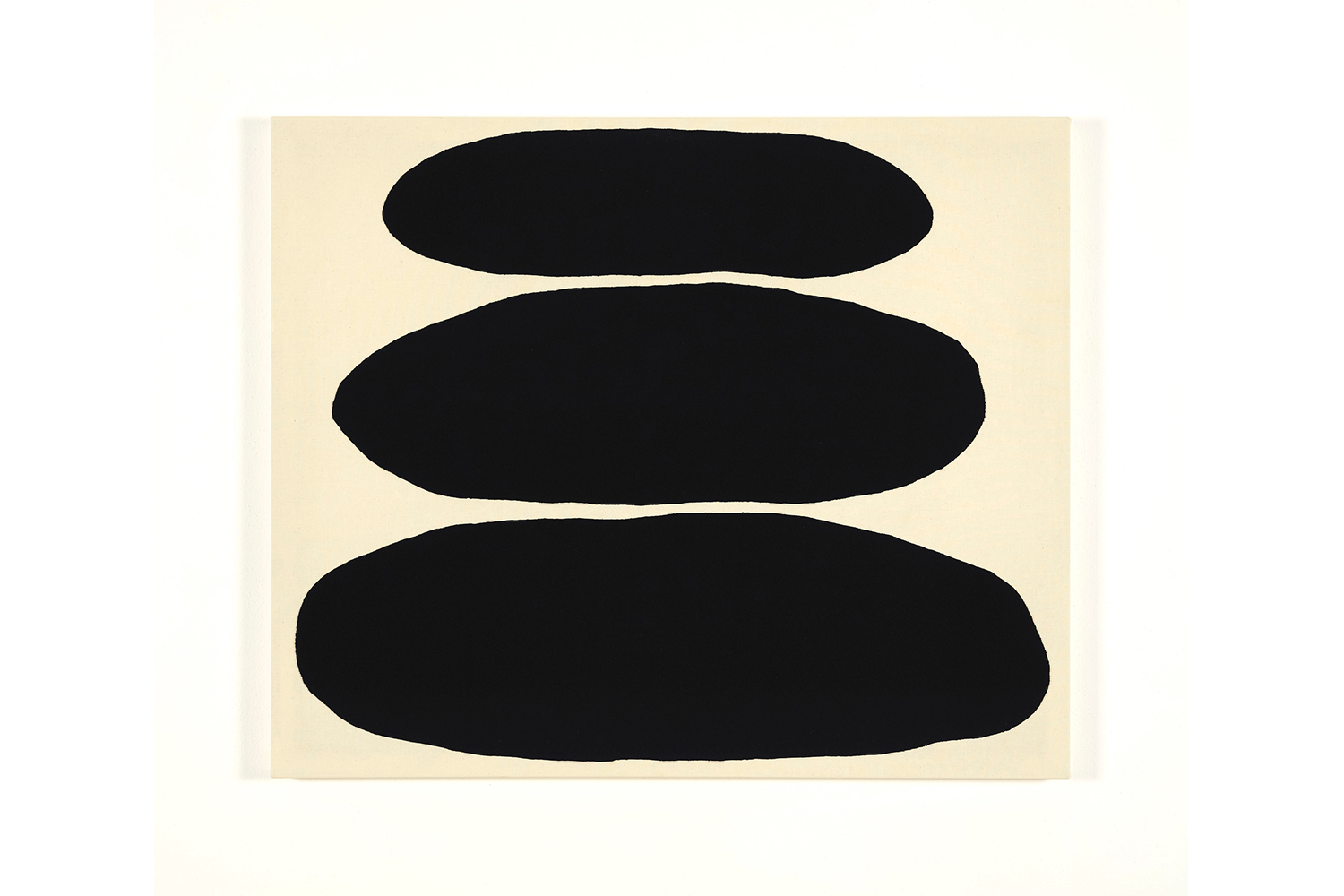

If Agnes Martin’s drawings and paintings are essays on “inwardness and silence,” as they have previously been described, then Adelaide Cioni’s are songs. She calls the fabric pieces in the opening gallery — which spill out and upward, and hum through Mimosa House’s large window on to the street — “Songs,” and each song has a dedication: for the sea, for fire, for Sol LeWitt. These sheets of muslin, usually stitched together with a central seam, unevenly cut down the edges and stapled to a wooden bar across the top edge, hang roughly and simply, softly dancing, their frayed ends swaying. The relationship with Martin goes beyond Cioni’s use of pattern, line, and color. Like Martin’s works, these songs become hymns, prayers: meditations on drawing and nature, on the human itch to instill order on the chaos and chance of the natural world.

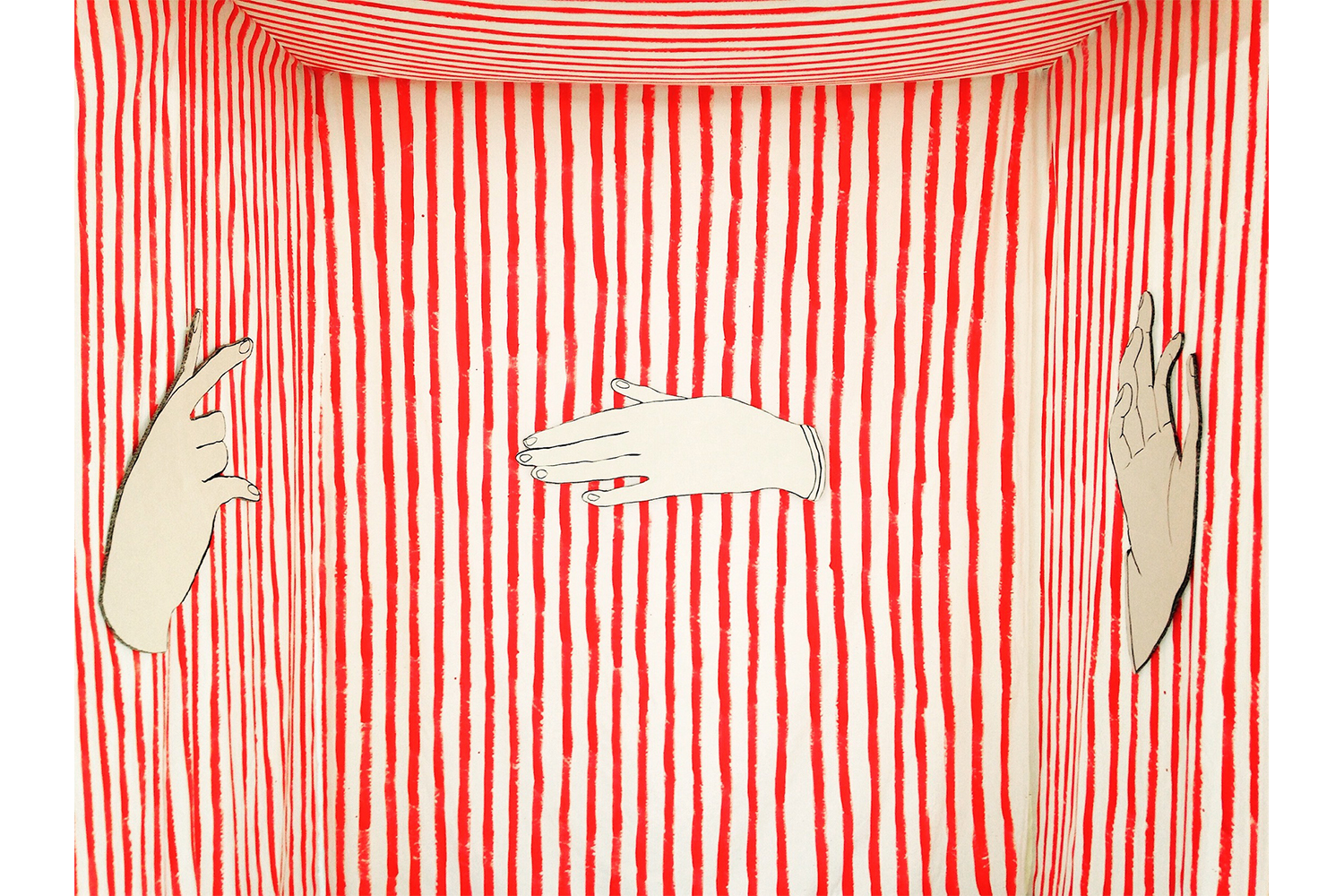

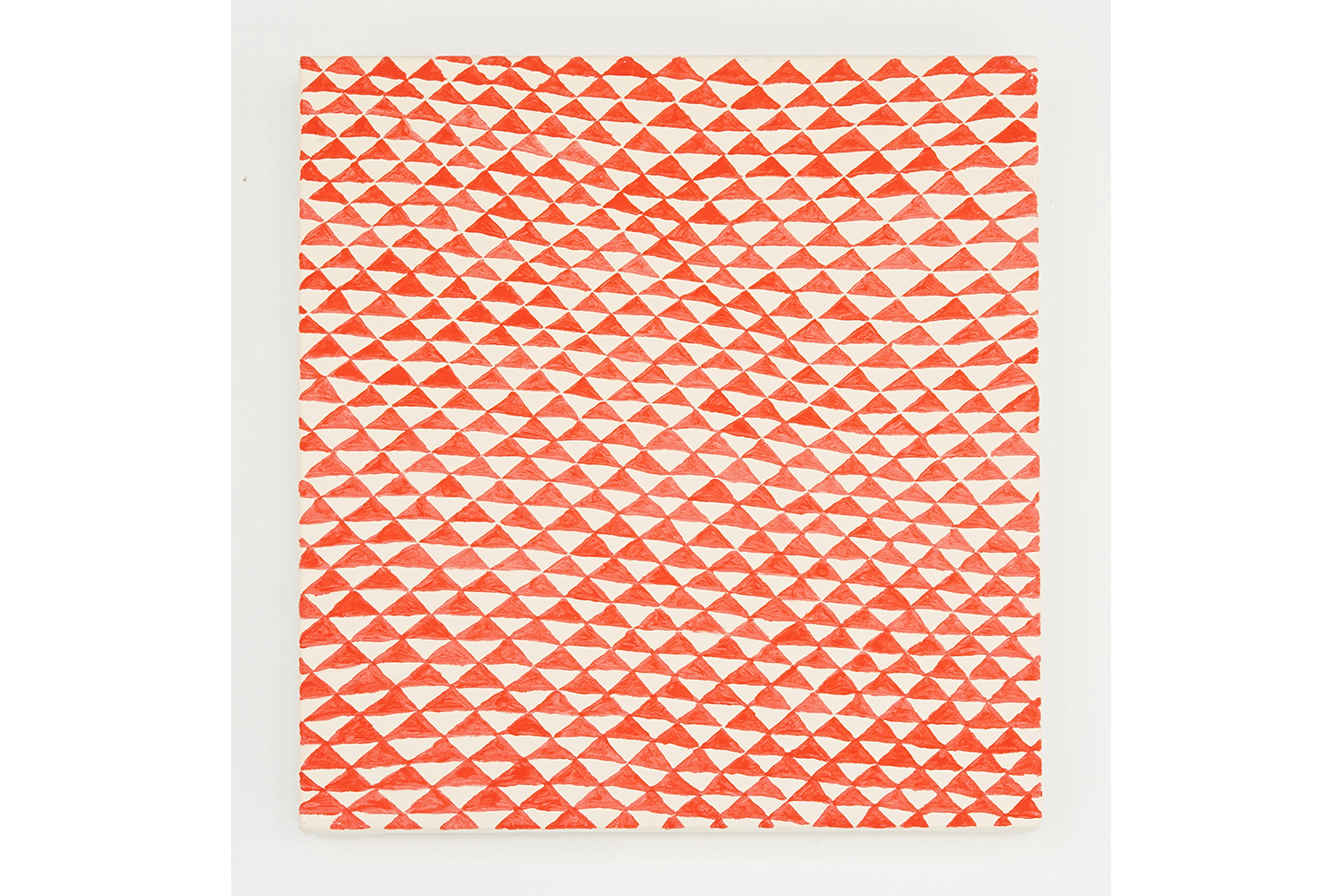

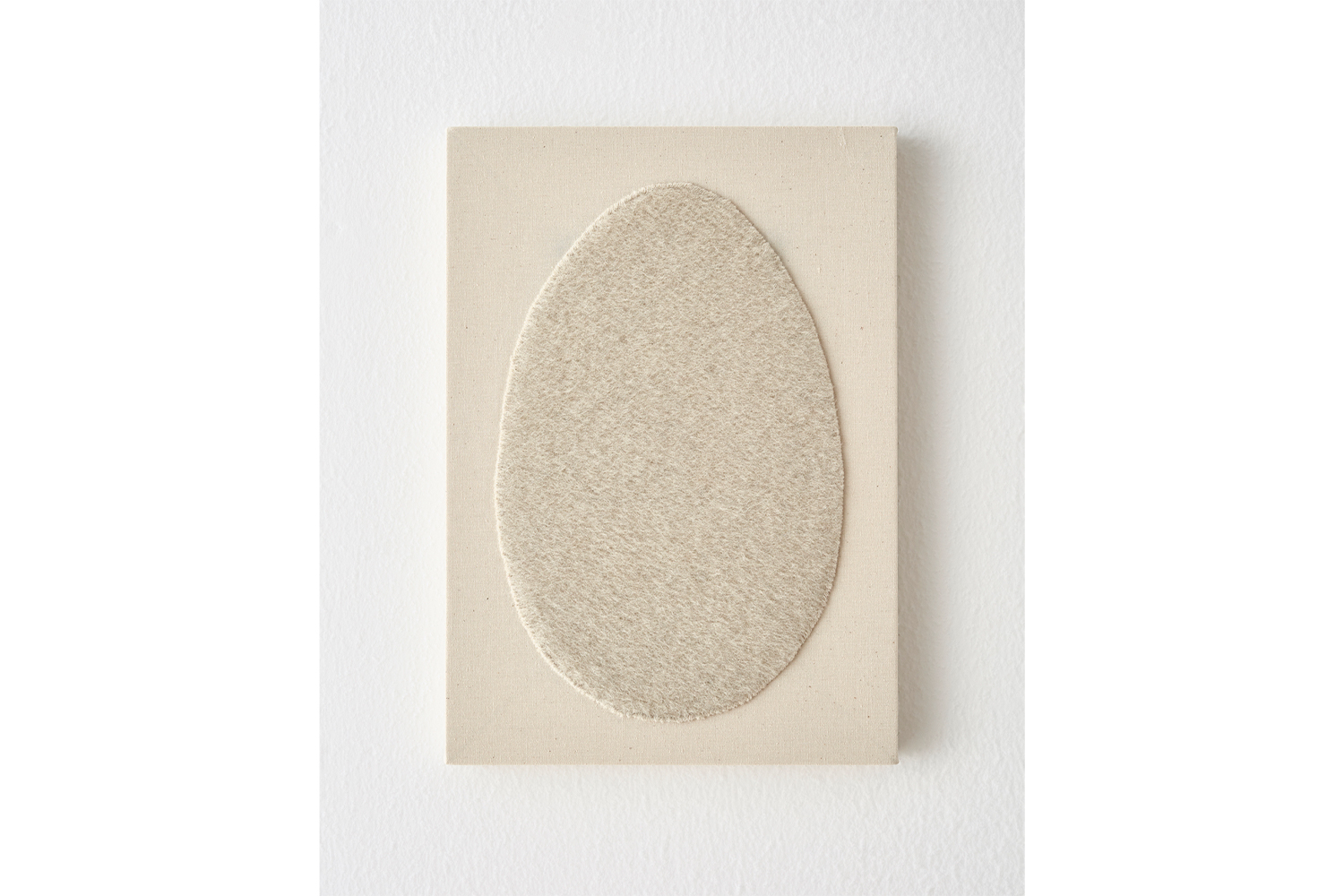

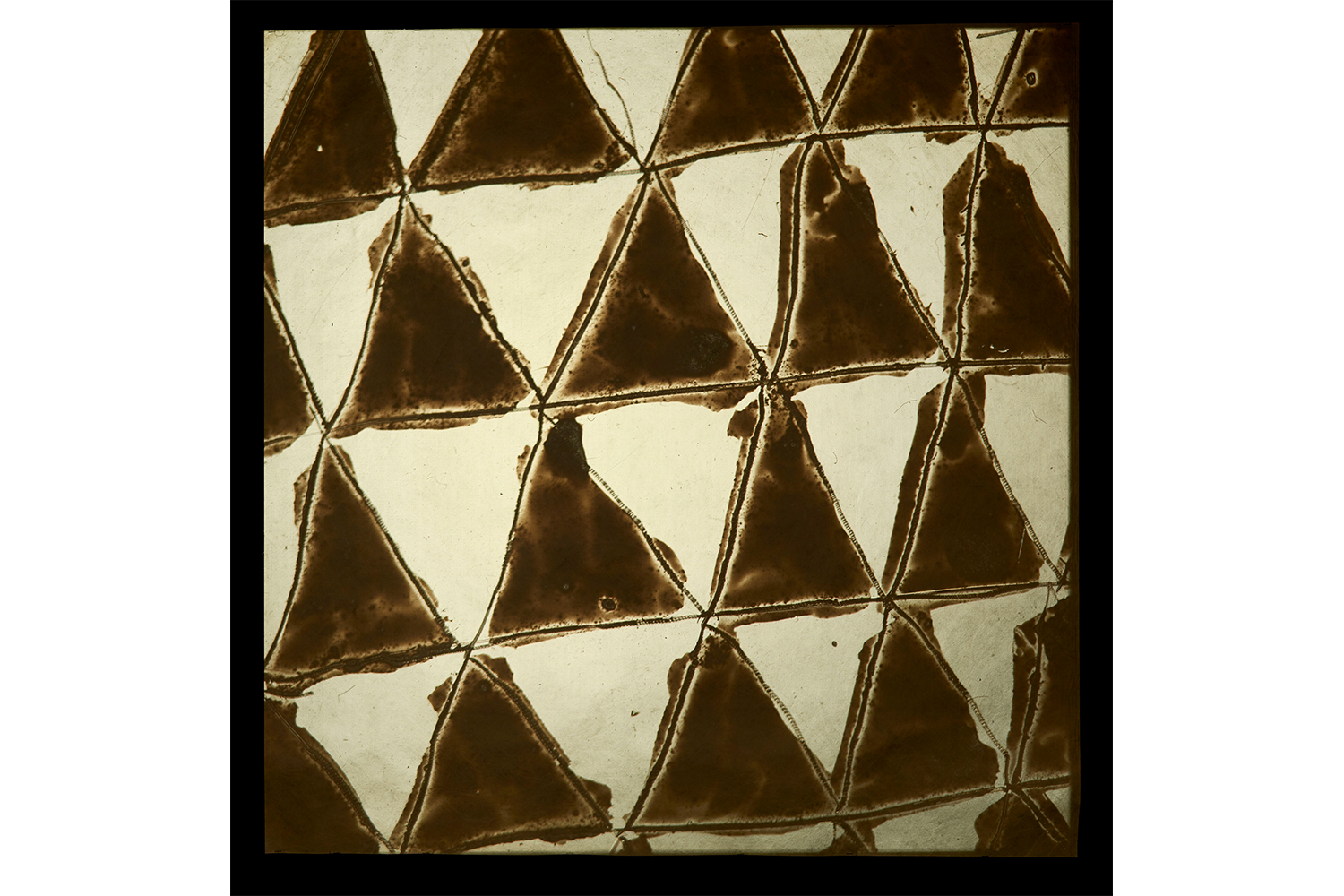

The title of this exhibition, Ab ovo, translates to “from the egg,” and the show is an approach toward primacy of form. Before the image, there was the line; before the line, the story, the idea, the impulse. Cioni looks to prehistory for patterns that repeat within nature and across geographically disparate cultures: the wave, the circle, the square, the cross. A thistle here echoes ancient Egyptian drawings of artichokes — the complexity of Fibonacci’s scaly rosette tamed into a matter of straight lines and curved triangles. All matter can be communicated this way, and yet it is always just that: communication. A former literary translator of Lydia Davis and David Foster Wallace, Cioni now uses drawing similarly to translate, to speak through, always conscious that in this passing through, the text inevitably picks up pieces of oneself that cling like lint to the translation. Of nature, she says, “Every artist looks at it and knows they are going to fail.” Yet the attempt is as infinite as the pattern. And, like nature, which remains stubbornly accidental and incidental, Cioni does not seek perfection. A simple pattern of triangles is interrupted by a red dot, a blot of dropped paint that breaks the viewer out of meditation and recalls the artist’s hand. In what may at first appear as purely mathematical, ordered intellect, the body is always present.

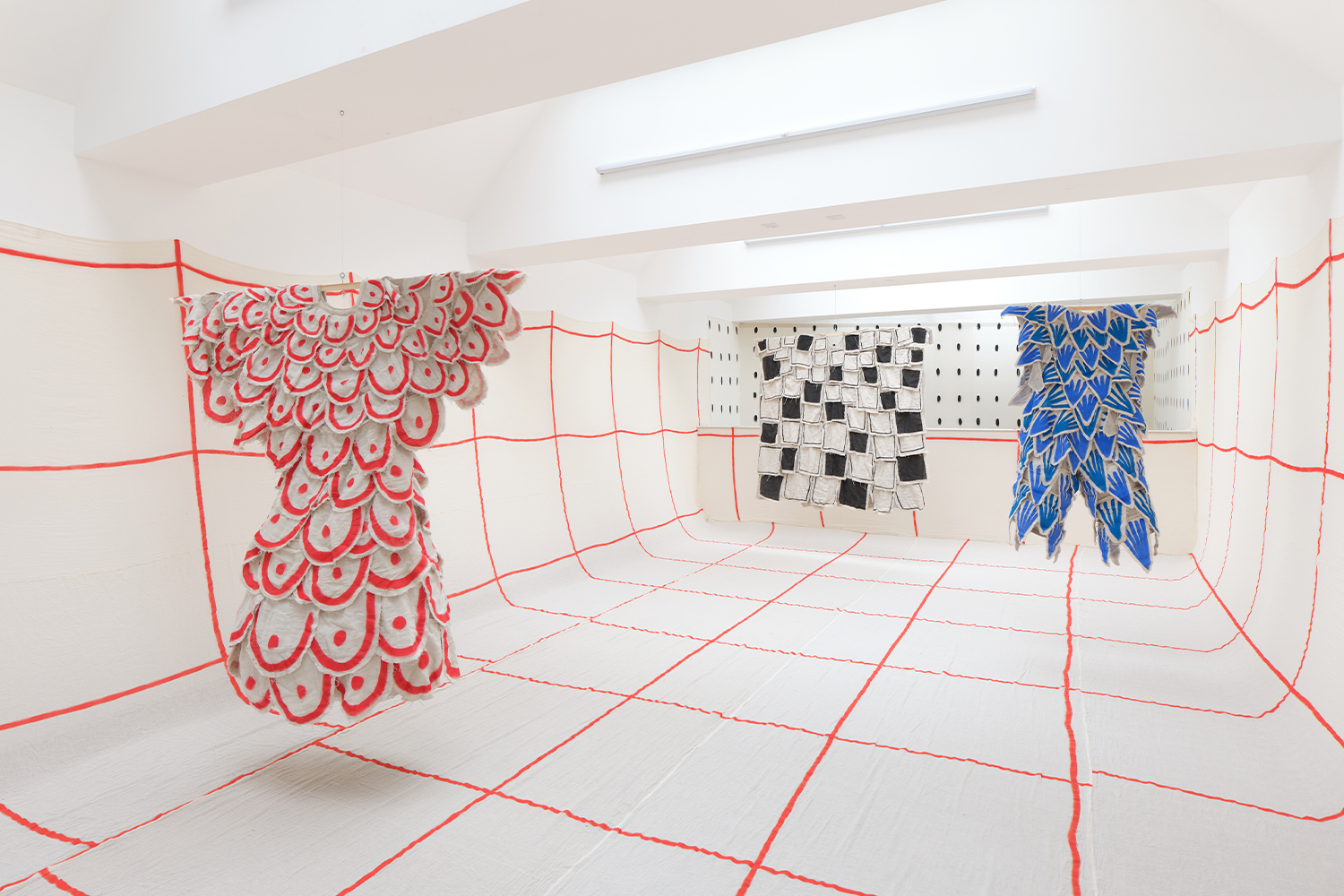

It is impossible to walk through the show without being conscious of one’s own body, navigating the intestinal labyrinth of suspended fabrics that funnel one through into an eruption of pattern. Whole rooms are overlaid with repeated marks and lines, implicating us, and at times dancers who improvise responses to the square, the circle, and the triangle, in this kind of weave. Despite the ubiquity of these shapes, Cioni commits to the everyday unseen — what Deborah Levy calls minor characters — a supporting cast of quotidian objects that settle like grains in one’s memory. Moving through the show, forms echo the artist’s undulating lines: palms in her Super 8 film Kew. A Conversation in Green (2019) dance and drip and interweave like fabric, and a robin alights on a branch, recalling a dancer’s costume of triangular shapes like birds’ feet. The sea is a recurring presence, hand-stitched as blue woolen waves onto flannel, vibrating across one’s vision as some patterned canvases seem to glitch of their own accord. In the performance, one of the dancers’ costumes — burlap circles overlapped again and again into a kind of tunic — ripples like fish scales as the movement builds. Something inward and as utterly inexpressible as energy is pulsing outwards, a rhythmic vibrating that could be scored as pattern but yet would always miss. The truth is in the splatter, the song, the fray: the space between and amidst the lines, that which can never be translated.