Talk about overproduction. With “What Do People Do All Day” and “Boulevard of Crime” Simon Dybbroe Møller doubles down and presents two seemingly unrelated shows at Francesca Minini, each with its own title and press release. In a further move (á la Michael Asher) the artist has intervened in the layout of the gallery, swapping the office and gallery spaces to display What Do People Do All Day (2020–22). Neatly arranged upon the staff’s worktables, their desktops, tablets, and laptops are synched to play all four episodes of Dybbroe Møller’s ongoing series of short films: a televisual update of Richard Scarry’s 1968 children’s book of the same name, in which the inhabitants of the so-called Busytown ply their daily trades in familial, well-established roles that ensure the smooth running of a microcosm of society. Rather than anthropomorphized animals going about their business, though, Dybbroe Møller has cast good-looking models, wind-blown and soaked in water, who strip off their uniforms and fuck. Work, as it is represented by the artist, is less traditional and more twenty-first-century oriented — abstract, fluid, and libidinal. After telling me he’s currently reading What Do People Do All Day to his kids, a friend at the opening remarked that we’re all sex workers now. Given that screen space is where many employees operate, the daily routine of the gallery is also implicated. Whenever a visitor enters the gallery, the films must be played, interrupting whatever labor is being done. True to form, when I call to ask for images of the show, the person I speak to says they’ll send them once visitors have left.

Alongside this, Dybbroe Møller has also mounted “Boulevard of Crime” — a parallel if somewhat niche exhibition that uses Louis Daguerre’s pioneering photograph of the Boulevard du Temple in Paris to speculate on a facet of industrialized society, namely commerce, as captured by the medium in its early formation. Daguerre’s image — what he coined a daguerreotype — is historically debated to be the first photograph to contain an image of human beings, in this case tiny, blurred figures of a shoeshiner and a customer that survived the five-minute exposure. The artist, however, is more intrigued by the fact that the scene in which these persons are engaged is transactional. One is working for the other, or, perhaps more specifically, in the employment of a service industry. Just as some of the (new) work force that appear in What Do People Do All Day are now synonymous with the gig economy, the labor market in Daguerre’s depiction is one that is in provision of others.

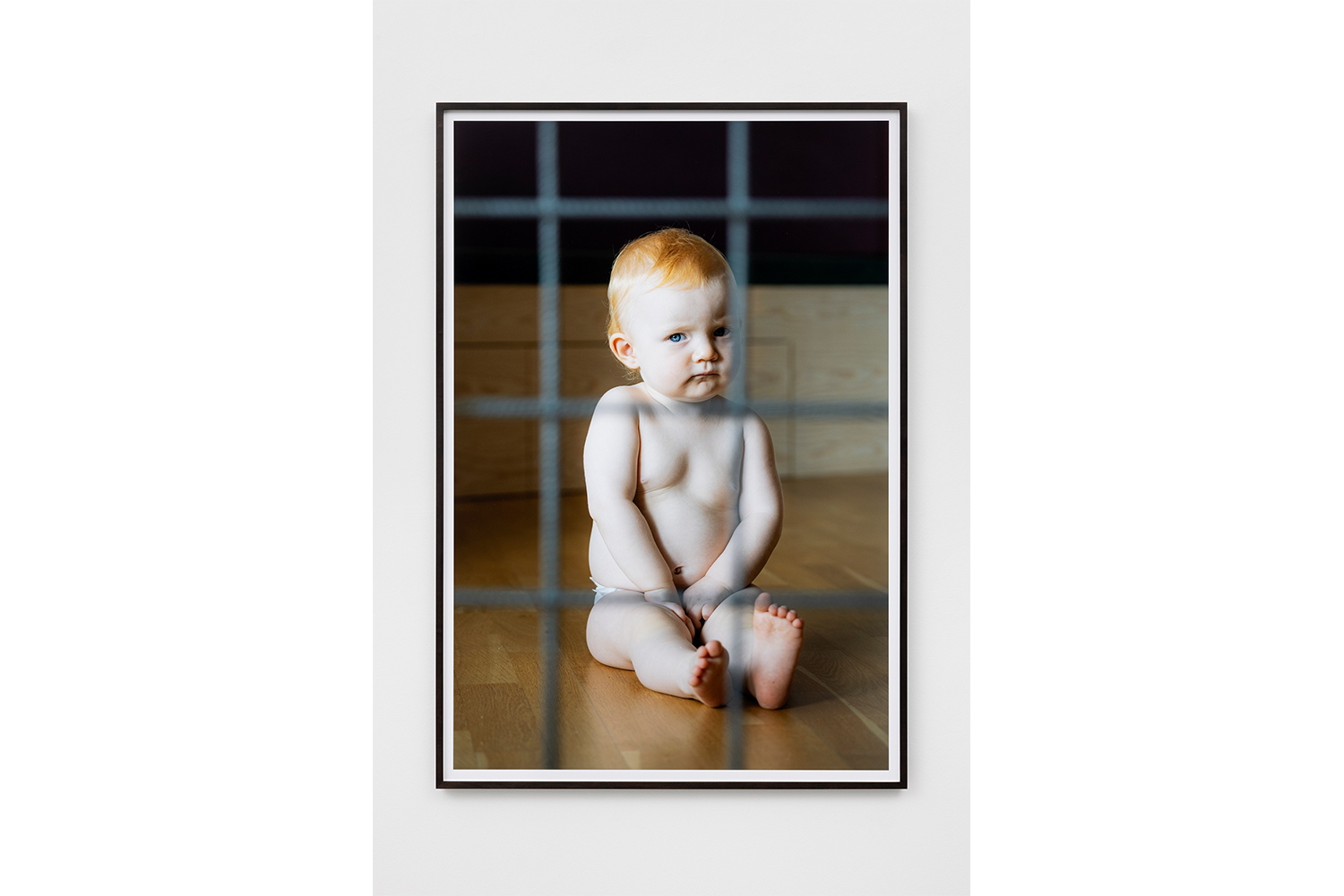

On the other hand, the artist plays up the insinuation of criminality (or, more fittingly, crime as a context) that photography continues to be an accessory to. Despite the Boulevard du Temple once being known as the “Boulevard du Crime,” the relationship between the two is a misnomer. Rather, the thoroughfare earned its nickname because its theaters were known for staging crime-themed melodramas. Before becoming inventive with photography, Daguerre ran a diorama theater. Thus, crime is linked to theatricality, and I get the sense that, for Dybbroe Møller, photography becomes a stage upon which to enact these ideas. For instance, a series of large-scale color photographs depict two women (Sisters, 2022), a red-haired infant (Baby, 2022), and a bouquet of flowers (Tulips, 2022) seen from behind barriers of various kinds — from recognizably vertical jail bars to chain-link fencing. Which side of these the subject and viewer is on is left ambiguous, although the suggestion is, as an onlooker, we are on the outside: the innocent looking at the guilty. The camera captures its subjects and incriminates them.

Yet crime is also a trade. Out of all the works, Boulevard of Crime I–III (all 2022) neatly encapsulate the complicated relationships between work, transgression, and theater proposed by this particular show. Strung up by their laces, several pairs of small, shiny black shoes hang from miniature, replica streetlights commercially produced in the style of nineteenth-century Parisian gas lamps. Shoes caught on telephone wire is a folkloric image of criminal transaction — a supposed tell-tale sign of meetups and drug deals. Positioned throughout “Boulevard of Crime” like props, Dybbroe Møller’s sculptures dramatize the exhibition as a space in which working through photographic practice is like revisiting an unsolved case file.