It is hard not to draw connections between the sense of confusion, claustrophobia, and scarcity created by two Sturtevant (1924–2014) works now on display in London, and emotions felt in the face of a swelling cost-of-living crisis. An approximation of a sadly stocked shop, Sturtevant’s The Store (1967) assembles a collection of groceries naively sculpted from plaster. Seen in 2022, this historically important re-making of a work by Pop artist Claes Oldenburg provokes comparison with empty post-Brexit shelves and thoughts of a looming winter of adversity for many.

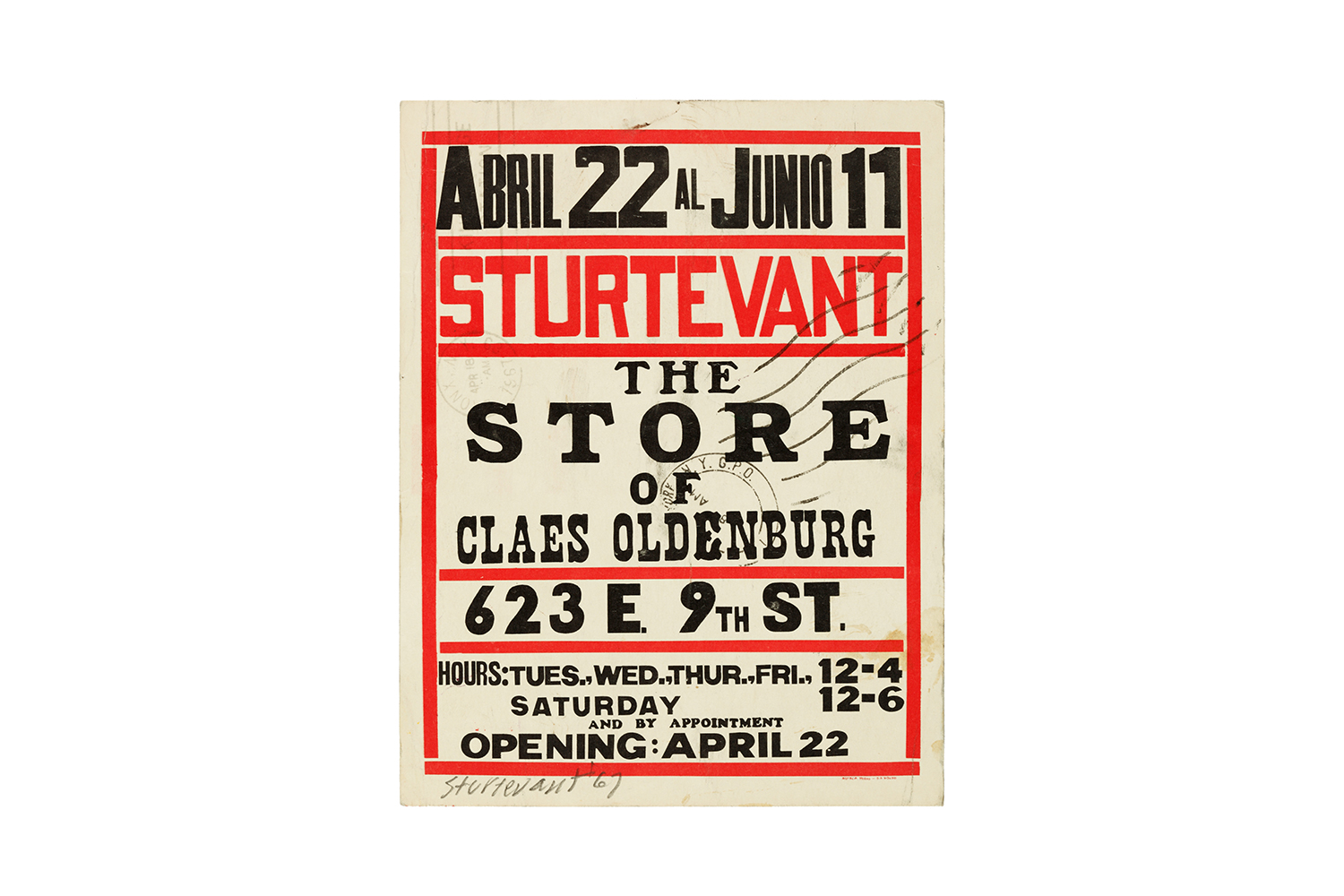

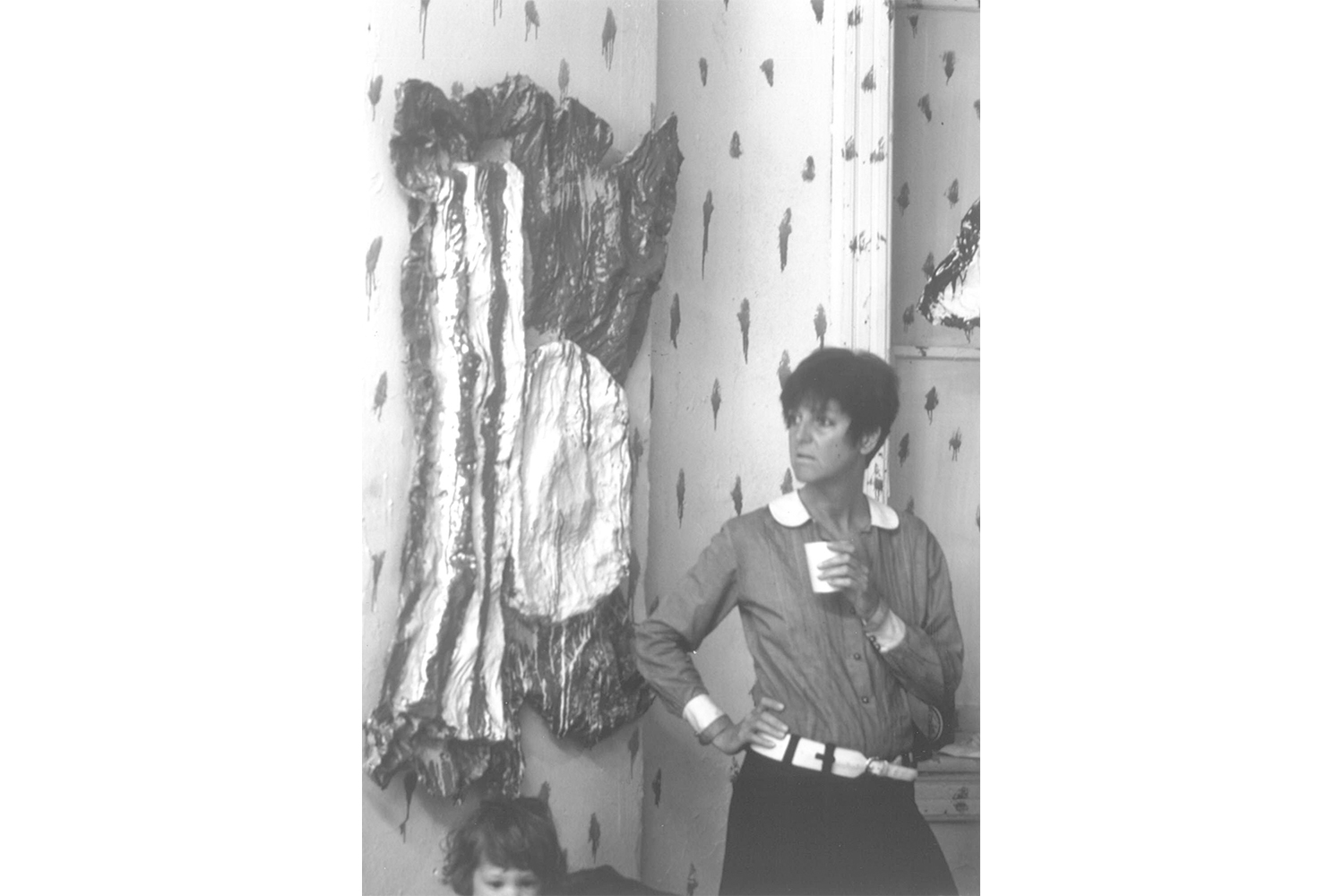

American artist Sturtevant made a career out of generating uncertainty by making other artists’ work. Challenging ideas of authorship and originality, she is famed for reproducing pieces by the male stalwarts of American Pop — Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, and Frank Stella, among other contemporaries. In making The Store (1967), Sturtevant hired a shop front on Manhattan’s Lower East Side and displayed the plaster objects now exhibited at Thaddaeus Ropac. This was part of a Happening that re-enacted Oldenburg’s already-famous 1961 performance of the same name. For this, Oldenburg (who passed away earlier this year) turned Green Gallery in New York’s East Village into a storefront filled with food, clothing, and hardware. Fifty-five years on, while the repetitions and time leaps are dizzying, the iconoclastic vim of her initial 1967 presentation has worn off. Originally met with hostility, Sturtevant’s once-audacious claims of ownership are now less interesting than the feelings of stasis and hopelessness that this work evokes.

Inedible and crudely formed, the object remnants of Sturtevant’s Happening — chocolate bars, a burger, a fried egg, a butter pat, cigarette butts, and a cake slice — sit on plinths within this exhibition. Although these child-like approximations of foods humorously undercut the reverence of their pedestals, her unoriginal confections offer no seeming value. They are limp and lackluster. Useless. We know that they are copies, but Oldenburg’s better-known “originals” seem inconsequential. Rather, what resonates more deeply is their seemingly helpless, empty nature. These artworks are eternally stuck in a loop, as if their maker had no means other than mimicry and repetition available to her. Being in this meager food store evokes a character in desperation. Or someone, something at its wit’s end. Oldenburg’s store provoked comment on the shifting boundaries between art and commodity. Sturtevant’s sickly version appears to be made by someone incapacitated by the weight of patriarchy and capital.

Heightening the sense of claustrophobia, Sturtevant’s film The Dark Threat of Absence (2002) acts as a backdrop for the fourteen objects comprising Sturtevant’s The Store. In this ominous video Sturtevant re-enacts Paul McCarthy’s film Painter (1995), in which McCarthy himself poses as a version of Willem de Kooning. With Sturtevant-as-McCarthy-as-de Kooning, the endless cycle of mimicry and re-making continues. Re-staging aspects of McCarthy’s work, Sturtevant is seen as a giddy, ranting artist adorned in a blonde wig, a bulbous prosthetic nose, and blue overalls. As with McCarthy, at one particularly grating moment the painter is seen hacking at her own giant prosthetic hand with a meat cleaver. Later a ranting character sniffs at a bare bottom. High-pitched screeches about money are heard throughout, and in this double-channel work the artist is juxtaposed with footage of ketchup and cocks. The image of a genius painter in their studio is deflated. The artist is replaced with a ranting, delirious amateur; comparable thoughts regarding unqualified and truth-denying bureaucrats are unavoidable.

With this revisitation to these two Sturtevant works it is striking how materially different the artist’s repetitions are from her original source materials. In her film, we see new repetitions that aren’t present in McCarthy’s, and also the exclusion of large parts of his work. Sturtevant’s repetitions are full of gaps. Art history may have finally hailed Sturtevant as the great appropriator, an artist who preceded the likes Sherrie Levine and Richard Prince, but in her practice she avoided mechanical reproduction and rather chose to repeat solely from memory. The erudite use of this technique sews scarcity and voids into her works, brilliantly setting her apart from her contemporaries. Revisiting Sturtevant’s work half a century on, this lack is felt, and resonates with difficult feelings associated with hopelessness and emptiness in a period of material retraction for many.