A Conversation with Jenna Sutela, Jakob Kudsk Steensen, teamLab, and Marshmallow Laser Feast.

“The Uncanny Valley” is Flash Art’s digital column offering a window on the developing field of artificial intelligence and its relationship to contemporary art.

“The Uncanny Valley” is Flash Art’s new digital column offering a window on the developing field of artificial intelligence and its relationship to contemporary art.

In Solaris (1961), Stanisław Lem wrote, “Man has gone out to explore other worlds and other civilizations without having explored his own labyrinth of dark passages and secret chambers, and without finding what lies behind doorways that he himself has sealed.” For the latest edition of “The Uncanny Valley,” four leading artists in the digital art space –– Jenna Sutela, Jakob Kudsk Steensen, teamLab, and Marshmallow Laser Feast –– unseal magical realities in ways that would be inconceivable with traditional media.

Mimi Nguyen: We spend a significant part of our lives immersed in mobile devices. Your recent project “I Magma App,” curated by Ben Vickers and Kay Watson at the Serpentine Gallery in London, was your first work using augmented reality technology. Can you tell us more about this project?

Jenna Sutela: “I Magma App” is part of a twofold commission between the Serpentine and Moderna Museet. The work, I Magma (2019), consists of two parts: a physical installation of lava heads, with blobs of liquid and color in motion, provides a seed for the machine learning–based generation of images and text in a mobile app. One of the starting points of the project is the lava lamp as the original psychedelic technology, designed for “those about to trip,” as Timothy Leary put it. Another one are the deep-dreaming artificial neural networks that present a more contemporary image of access to “the thing in itself.” The installation is inspired by the history of experiments in using lava lamps to generate randomness, as conducted by the engineers at Sun Microsystems in the 1990s. Instead of randomness, however, my work looks for patterns, signs, or meaning in the lava movements.

Valentino Catricalà: In this work, you have combined a form of artificial intelligence with nonhuman, mystical intelligence. What is the meaning of this combination?

JS: A lot of my work looks at, or looks for, the ghosts in the intelligent machines of our creation that are increasingly shaping our reality. On the one hand, the work is about getting in touch with the nonhuman condition in which computers work as our interlocutors and infrastructure. On the other hand, it’s about the computers getting in touch with the more-than-human world around them. Nimiia cétiï (2018) is perhaps the best example of this. The work uses machine learning to generate a new written and spoken language based on a computer’s interpretation of a Martian tongue from the late 1800s, originally channeled by the Swiss French medium Hélène Smith and now voiced by me, as well as the movement of Bacillus subtilis, an extremophilic bacterium that, according to recent spaceflight experimentation, can survive on Mars. This bacterium is also used in the making of nattō, or fermented soybeans — a classic Japanese probiotic considered a secret to long life.

In the nimiia cétiï project, the machine is a medium, channeling messages from entities that usually cannot speak. But the work is also about intelligent machines as aliens of our creation. There’s an interesting link between the project of talking with aliens and the problem of talking with machines. We built (at least some of) the aliens ourselves, and the challenge now is to understand the nonhuman condition of these machines.

MN: Marshmallow Laser Feast’s project We Live in an Ocean of Air (2021–22) invited participants to enter inside a sequoia –– one of the largest living organisms on earth –– using technology to bridge human and natural systems. The experience, in which our breath is visualized as air particles synchronized with our heartbeat and blood vessels, seems to probe humanity’s simultaneous reliance on and destruction of nature. Is there a hidden metaphor?

Marshmallow Laser Feast: There is exploration of interconnectedness. People bring life into this work. When you participate, the work comes to life — your heart beats, and you do not just go inside a sequoia but quite literally breath with the trees. It’s nice to operate in an environment where we can expose different scales: size — human to tree scale; or time — nonhuman time scales. The connectedness of things exposes another scale entirely. For example, where does the tree begin and the human being end? The movement of breath in this case serves as a metaphor for connectedness.

Thích Nhất Hạnh coined the term “interbeing” as a way of describing that our very existence depends on and includes the existence of everything else. By following breath, this concept becomes tangible — inside and outside become porous.

VC: Your work discusses the invisible world of relations between human and nature. How do you envision future transformations in the perception/conception of a mutant social and cultural reality?

MLF: The nature of perception places it firmly within the boundary of our skin. Our senses extend out into the world, but the limits of those senses leave us with an impression of reality. To be another, to see the world through the eyes of another, to step outside your skin, is a cure to the disease of human self-importance.

Science is a window that allows us to look through and beyond our own experience, to understand the complexities of things hidden from the naked eye. Pulling these unseen corners of reality into the field of human perception is at the heart of our work. Immersive experiences can fuse those dimensions of reality into your story, flavoring the way you see yourself and the world around you. The ability of virtual reality to take you out of your body — to see the world through the eyes of an animal or a tree or a forest — fascinates us and is a great way to shake off the feeling of human superiority. It’s a really nice idea to experiment with sensory perception beyond the limits of the human being. For example, the vision of a dragonfly is profoundly different to that of human beings.

MN: Speaking of the Anthropocene, orchids are said to be the last plants to appear on earth. They are central to teamLab’s Zen gardens, while their seeds require a specific species of fungus in order to grow. Humans can learn a lot from fungi, from their optimization of distances and through our shared natural symbiosis. In your works, often the boundaries between ourselves and the world become blurred through extreme immersion. What is the greatest challenge of working on such digitally complex projects?

teamLab: Creating art is always difficult. Our artworks are created by teams of specialists through a continuous process of creation and thinking. Although the large concepts are always defined from the start, the project goal tends to remain unclear, so we need the whole team to create and think as we go along.

VC: Jacob, your work is highly connected with the idea of an “other” environment, and with the latest theories regarding the Anthropocene, a world in which everything is connected. The making of new environments expresses not only a visionary intent, but also connects to the actual sense of place and its features, as in the work Berl-Berl (2021). What’s the border between the creation of a new reality and the deepening of research of the natural world?

Jakob Kudsk Steensen: I feel the concept of reality is fleeting, loosely defined in different contexts, and shifting in definition when you move from your home to work, to religious spaces, workspaces, art spaces, and scientific or cultural spaces. This can cause a space of stress, or feeling like your body and mind don’t always occupy the same space. We are also able to have planetary eyes embedded in us due to technology; you can chat with a friend, be in an intimate space and feel the soil beneath your feet, but then suddenly also look at earth from a satellite hovering far above. Or you can eat an apple off a beautiful tree, and two seconds later read about an earthquake or a disaster elsewhere. This creates temporal and spatial displacement, which I think starts to impact our psychologies and identifies us and our purpose in everyday life.

What I have learned in the past year is that I am drawn to working in “real” environments because it roots me. It gives me the feeling that what I make is real. It is fact — my doorway to the world. I also don’t think in terms of mediums but of channels in my work. So sounds and virtual environments are pathways into actual worlds outside, not just objects and artworks in front of us.

MN: Last year, Phytocene explored the microscopic interconnections of living bacteria and plant ecosystems. While MLF’s Observations on being (2021) is an omnipresent enveloping experience that renders our senses through sound and physical exposure to the ground. You’ve worked with some of the most incredible artists on this project, including John Hopkins for sound and Daisy Lafarge for text. How do you see the role of collaboration in art creation?

MLF: Collaboration enriches the process as well as the result. Every breath, every thought exists only in relationships, and so to embrace collaboration is to dive into the possibilities of being part of something greater than yourself. We have always found that the journey and the artwork has its own direction and life, which sweeps us along with it, and collaboration enriches that flow.

VC: Do you think that the pandemic accelerated such transformation processes? If so, in what direction?

MLF: The pandemic sharpened our focus on the fact that our existence is physical and virtual. Also, bringing awareness to the inner workings of the human body and global populations, it brought us closer as living organisms to super organisms. Things that felt like sci-fi previously have become lived experiences, and therefore inform any transformation of our reality.

Marshmallow Laser Feast, The Forest for Museum of the Future, 2022, Courtesy of Mashmallow Laser Feast and Sandra Ciampone.

VC: Jakob, the swamp is a recurring figure in your works. How can the swamp represent our new human condition, and how it has been developed in this work?

JKS: Wetlands, not only swamps, have been my theme the past two years. But earlier works like Aquaphobia (2017) and Re-Animated (2019) also took place in wetlands; the narrative of the locale was just less front and center.

We all originate from wetlands, and all major settlements are based on wetlands. The reason is that wetlands are like livers of landscapes, able to filter nutrients and create a fertile environment. The definition of a wetland is a location that is able to sustain freshwater on its own, which is what we need to survive. So non-nomadic populations have settled historically next to wetlands, or created artificial ones. However, in the eighteenth century, kings of Europe destroyed wetlands and spread the practice abroad. The reason is they became antithetical to modern spatial navigation — unusable for farm land, hard to move through, seemingly dirty and chaotic. Yet they are our source of life. Now we see issues with freshwater management and there are large projects to bring wetlands back. We cannot survive without them. They are part of our DNA.

MN: teamLab’s Continuous Life and Death at the Now of Eternity II (2019) is an algorithmic artwork that renders in real time. This ephemeral experience repeats the cycle of life and death, addressing seasonality and mortality through the rebirth of flowers. How does nature inspire you in your creative process?

teamLab: teamLab sees no boundary between humans and nature, and between oneself and the world; one is in the other and the other in one. Everything exists in a long, fragile yet miraculous, borderless continuity of life.

The work, Continuous Life and Death at the Now of Eternity II (2019), is in sync with the location it is exhibited in, reflecting the time of day and seasonal changes. While flowers eternally repeat the process of life and death, the world of the artwork becomes brighter as the sun rises, and darker as the sun sets. The real time in which the viewer exists, the flow of time of the city, and of the repeated life and death of the flowers all intersect and overlap while the viewer’s body, the city, and the world of the artwork remain connected. Continuity such as this is what teamLab is exploring through art.

VC: Jenna, your work has a connection with esoterism. For instance, in the video Nam-Gut (the microbial breakdown of language) (2017) you presented a biological poetic culture based on a “wetware random number generator.” The changes in the living material also shape a text inspired by an ancient Sumerian incantation, a nam-shub. Can you please tell us more about this relationship with esoterism?

JS: I was actually introduced to nam-shubs through science fiction, in particular Neal Stephenson’s cyberpunk classic Snow Crash (1992). A nam-shub is a form of speech that’s thought to have magical power, and I wrote one about code laws and the gut-brain connection for the “Gut-Machine Poetry” (2017) project. Then, I let the movements in a kombucha ferment, basically the movement of yeast eating sugar, affect the jumbling of letters in my nam-shub via an algorithmic process. Like this, the symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast (SCOBY) reinterpreted my text. The nam-shub in Snow Crash deals with universal language, and I’ve been curious about interspecies communication, including the kind that happens in the context of our bodies. By inserting a SCOBY into the guts of a computer, I wanted to bring attention to embodied cognition and how, for example, our microbiome plays a role in the course of our thoughts and emotions and somehow speaks through us. What if a machine could experience a similar symbiotic relationship. Anyway, back to your question, I would, perhaps, change the word “esotericism” to fiction.

MN: MLF worked very closely with Merlin Sheldrake, a fungi expert, biologist, and author of Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds, and Shape Our Futures (2020). Jenna, you have also looked at the symbiosis between biological — especially slime molds — and computational systems that speak “Bacterial-Martian.” What was your inspiration?

JS: Probably the idea of wetware. Next to software and hardware, wetware being some kind of living computing matter, like, for example, the human brain or a pond ecosystem in the early alternative cybernetic experiments by Stafford Beer. Coming across Physarum polycephalum, the single-celled yet “many-headed” species of slime mold, which is known as a natural computer and used in mapping and robotics experiments, was also a huge inspiration.

VC: Working on microorganisms is today related to a new idea of Human Being and a way of thinking about nonhuman entities as active actors in the making of the world. Your work is a way to perceive nonhuman entities around us, and to look beyond our anthropocentric vision. Why does bacterial life permeate so much of your work?

JS: An important part of my project is to acknowledge ourselves as a community of organisms — or, after Lynn Margulis, consider ourselves as entities made of many species that live in, on, and around us, all inseparably linked in their ecology and evolution. Holobionts, essentially. Besides ancient bacteria, artificial neural networks and intelligent machines are also increasingly part of our lives, shaping our realities in ways that are sometimes beyond us. I think we should seek to connect with or sense these invisible life forces among us, developing new sensibilities in the light of novel experience.

MN: The endless new possibilities provided by more sophisticated hardware and software hold the promise of new relations through the language of multimedia. What’s next?

teamLab: We really don’t know! We should just try to keep on creating. We should continue asking questions — because that’s what art is for. We have many exciting exhibitions and museums opening in cities all around the world, including in Beijing, Hamburg, Utrecht, and Jeddah.

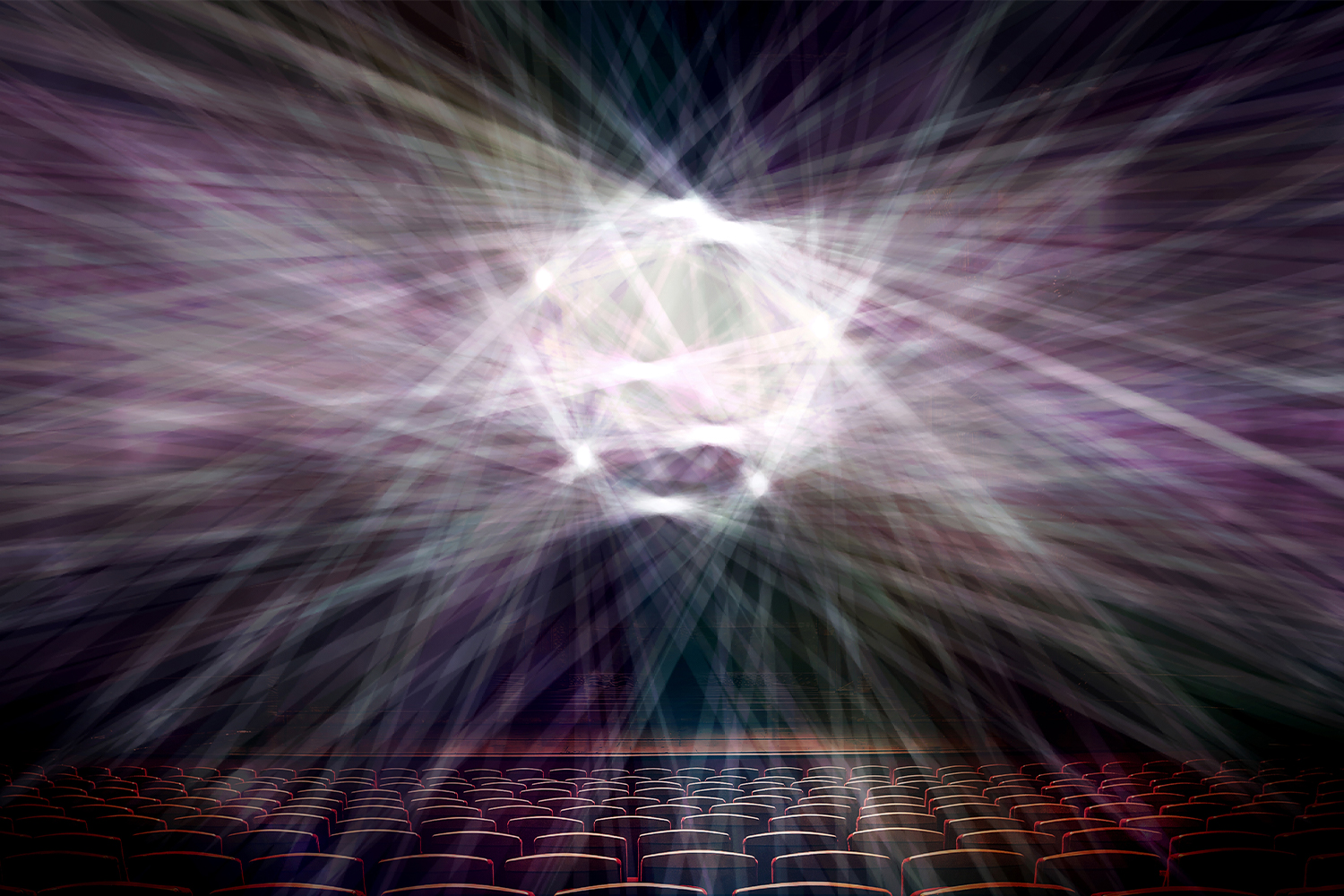

In Geneva, we are honored to be part of a production of Turandot, taking place at the Grand Théâtre de Genève this summer from June 20 to July 3, for which we are the creator of scenography, digital, and light art. Transcending the concept of stage design, the opera space is created by a sculptural space of light. The scenography, which has been in planning and production for the Geneva premiere since around 2017, immerses and unifies the cast in the light sculptures, creating a space where the stage and audience are continuous without boundaries.

MLF: What we find interesting is not necessarily what software and hardware advancements present but how culture and cultural practitioners invite the interplay between audiences and their work. This is where the next shift will emerge from.

The digital native generation is already consuming media in a parallel metaverse while also facing the sobering realities of a global struggle due to the decimated liveliness of the planet. What comes next should embrace the planetary boundaries of the living earth and shift its priorities for humans and more-than-humans equally. We need to tell new stories that highlight the wondrous rhythm that connects us all; perhaps the new paradigm will position this notion at its core.

JS: I believe we should extend the input we offer machines to more-than-human contents, if possible — letting them experience the environment at large as best as we can.