Read in sequence, the names of the Kaunas Biennial’s main locations could compose the map of a role-playing video game in which the gamer must survive in a postapocalyptic, deserted metropolis: the House of Basketball, the Devil Museum, the Zoology Museum (though, truth be told, the latter place is more impressive for its appearance than its name). The exhibition, curated by Josée Drouin-Brisebois, also extends elsewhere, giving the artworks a chance to converse with the daily routines of the city, and the visitor a decent grasp of the geography of Lithuania’s second largest city, which once served as the country’s ad interim capital between the two world wars. The term “apocalyptic” is probably apt, not as a thematic reference to the healthcare-political turmoil we have sunk into — an angle the exhibition does not dwell on, at least not directly — but in its etymological origin descending from the ancient Greek apokálypsis, to remove the veil. The show aims to address storytelling, folk and fairy tales, as its theme, but takes a decidedly different stance from the one we have become accustomed to from allegorical, cautionary stories (in the Aesopian fashion) that direct us with a steady hand toward a single “moral.”

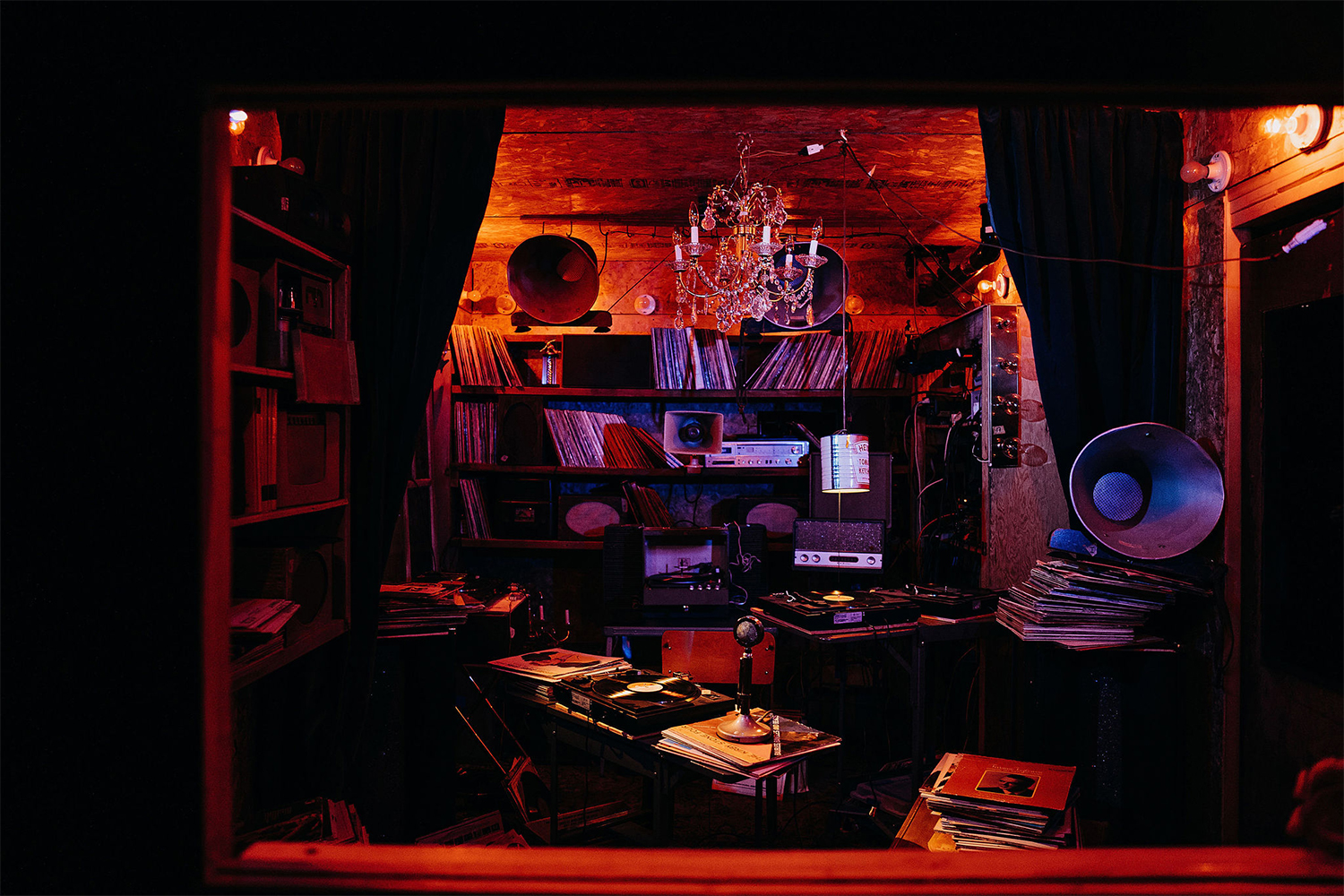

On the other hand, “Once Upon Another Time…” underlines the negotiations, the Chinese whisper moments, the around-the-fire exaggerations or mutations, the sedimentation of atavistic, complex, or contradictory layers, that coat the seamless surface of the ready-made tales that are whispered by the bedside. Hence, we enter the House of Basketball (a building dedicated to the sport in which Lithuania has been a European superpower since the 1930s) and are greeted by the red curtain with which, in 2018, artist Petrit Halilaj, using stories and narratives of the small Kosovar village, revived the Yugoslav cultural center in his native Runik, which had been left abandoned after the Balkan wars. Beyond the curtain, an installation by duo SetP Stanikas threads together a collection of traces of a restless family past that mirrors the history of a country that has experienced centuries of tension and invasion from neighboring nations, and foreshadows the exact and balanced sculptural twist of Monika Sosnowska’s C and Concrete (2017). Upstairs, the story of the Soviet invasion is delegated to the intersecting voices of local radio technicians in Althea Thauberger’s newly commissioned Reverse the Antenna (2021). The bittersweet video piece is surrounded by textiles suspended from the ceiling by Laura Lima, Giedrė Kriaučionytė, Rasma Noreikytė, and Kapwani Kiwanga. The second floor ends with Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller’s Opera for a Small Room (2005), an exceptional automatic noir fiction that challenges the boundaries between set design and installation art, keeping the spectator suspended in the uncertainty of foreboding and derailing omens.

The Zoology Museum is gently alienating: a crowd of taxidermy animals, not located in dioramas or stylized reproductions of habitats as one would expect, but rather indexed in showcases with aseptic and administrative-office-colored backdrops. Here the duo Pakui Hardware invents a museum within a museum in which they arrange hybrid, invented creatures, whose possible kingdom of belonging is hard to discern. Emilija Škarnulytė’s exceptional work Absolute dating (2021) projects lights at given intervals generated by colored lasers, which produce moving patterns punctuated by the sound of ambient electronic music on a room populated entirely by mammals of various size. One is undecided whether the animals implicitly become a canvas on which to compose pictorial-like geometric sequences or whether, on the contrary, the museum is transformed into a kind of dance floor for those bodies that preserve a semblance of life for educational purposes. In the same building, at the end of a long and unadorned walkway, Jeremy Shaw’s Liminals (2017) is screened: a mock documentary of a future community trying out physical, spiritual, and psychedelic practices to regain the mystical capacity that was extinguished by humankind.

The Devil’s Museum, as the name implies, preserves artifacts from all sides of the world depicting the devil or rather — to return to the curatorial statement regarding folktales — all those creatures related by cultural or functional contiguity in various mythologies that monotheisms have baptized as demons. Here we encounter the mutant ghouls added by David Altmejd to the existing collection; the exquisite three-screen video projection What Happens with a Dead Fish? (2021) by Lina Lapelytė that expands on fragility, finiteness, and eschatology; and the video-cum-performance The Trampled Devil (2021) by Shary Boyle. Boyle’s video reconstructs the loss of the body of a statue of St. Michael the Archangel by transforming it into a series of characters associated with the occult and the hidden in various ways: from a witch to Andy Warhol, from a vampire to a tycoon. Also noteworthy is the initiative of artist and professor Artūras Raila, who invited a group of Belarusian students to imagine an exhibition on their country’s complex current historical moment, and the site-specific intervention by Augustas Serapinas, who transported a sauna bathhouse from the village Rūdninkai and placed it near the castle of Kaunas, an area that used to host settlements of similar wooden houses. Serapinas’s work literally translates the exhibition’s vocation to deal with stories that have been passed down, modified, or forgotten. “Once Upon Another Time…” not only reaffirms a vital and lively local scene, but also celebrates in an original and effective way — at a time when it is not particularly easy to do so — the residual mythopoetic and demystifying potential of contemporary art.