It’s a fairly straightforward affair: in Hulda Rós Guðnadóttir’s exhibition at the Reykjavik Art Museum, we see a three-channel video installation depicting workers in bright neon clothing stacking cardboard boxes on a palette. Similar boxes are stacked up to the ceiling of the exhibition space, setting the stage for the looped observation on the large video screens. The boxes are heavy, the workers sweat, moving quietly and precisely, a well-tuned machine. Rarely is the silence broken by an inside joke.

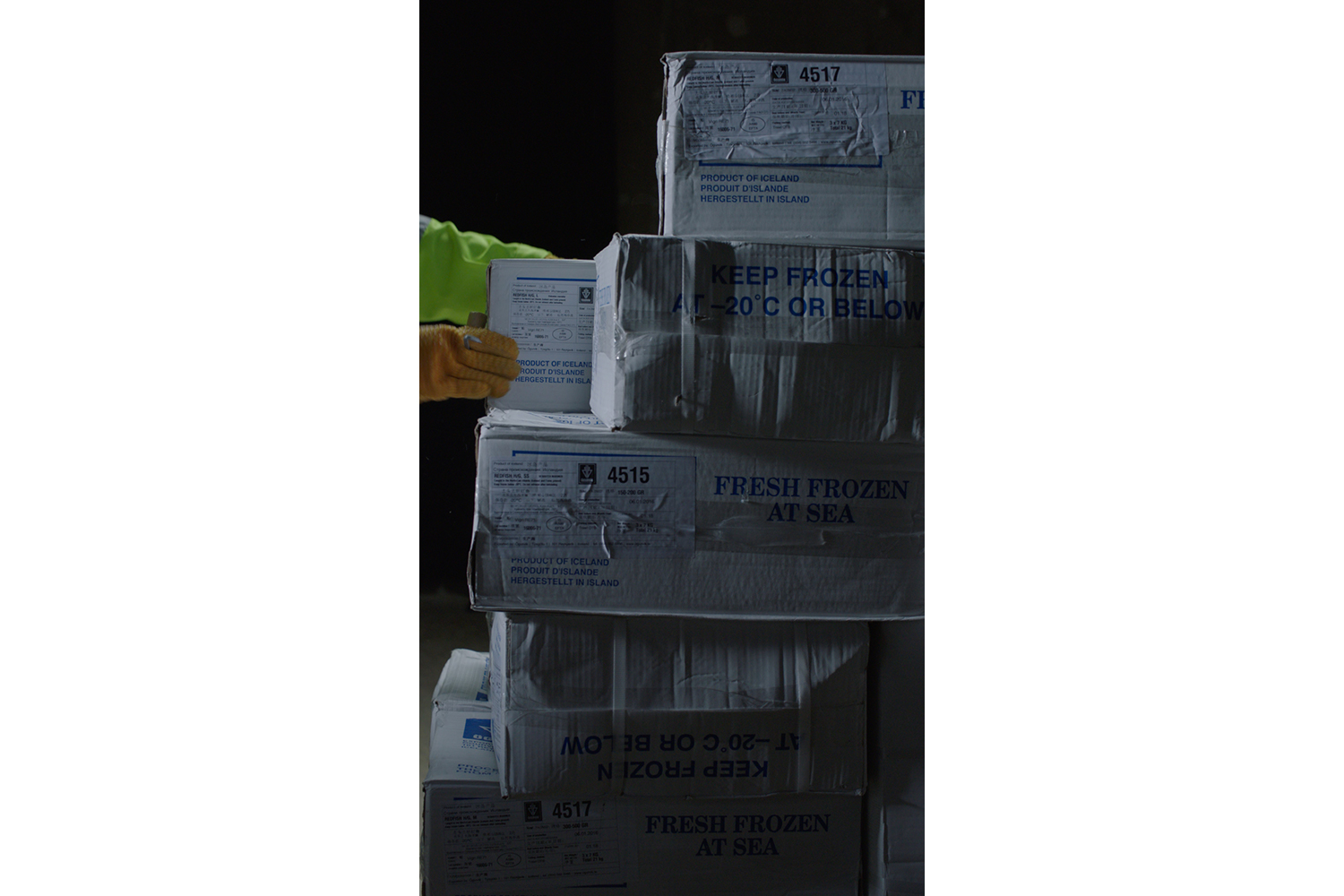

The beauty of attending the opening of an exhibition resides in the unexpected encounters. Here it is the workers in the video, who are visibly proud to be here. What does the installation mean to them? As if having pulled a trigger, Davíð takes me on his tour of the work, pointing at the cardboard boxes: “This is how the fish arrives here. The number on the box denotes if it’s white or red fish. Each box is at least 25 to 30 kg of deep-frozen fish. After a couple of weeks of fishing, the ships come into the harbor and are loaded to the brim. While at sea, inside the ships, the fish is already frozen and packed, either manually or by robots.

“Unloading the ships, however, needs to be done manually. When a ship comes in, we get into its hold and, standing on top of the stacked frozen boxes, start working our way down. We stack the boxes on palettes, which are lifted out of the hold by a crane. The boxes are frozen down to -30 degrees and are hard as a rock. The ship’s storage is two or three stories high. As we go further down the temperature goes down as well, and we put on additional layers of clothing. The constant movement is a necessity to keep us warm.

“But here,” he says, pointing at the video, “we were doing a performance,” and he gives me a wink. “The artist invited us to Leipzig, where we packed and unpacked the same palette with boxes filled with sand. This went on for forty-eight hours, around the time we need to unload a big ship. In Leipzig we had a blast and partied and it was warm. That’s why we break into a sweat. In the ship’s hull we certainly don’t,” he chuckles.

No surprise he feels confident talking about the project. Not only is it about him and his work, he has been working with the artist for more than five years. The installation on display is a condensation of years of research by the artist, which produced, among other works, a documentary film and said performance. The latter achieves the rare feat of presenting physical labor as the highly refined and effective piece of choreography it is, but without glorifying or scandalizing it. By taking it out of its context, reframing it in a theatrical setting, the artist gives it visibility, drawing it back into the realm of culture, making the abstractions of labor strikingly visible.

But showing it at this specific location adds another layer to the work. The Reykjavik Art Museum consists of several venues, the largest being Hafnarhús, a large converted warehouse on the old harbor. Heavy manual work took place here before it became a museum. Thus began a gentrification process that changed the area entirely. Warehouses were converted into museums, shops, or restaurants catering to tourists; a new opera house and expensive flats of arbitrary design arrived. The development echoes that in many other big cities, from Hamburg to Oslo and Copenhagen. Boats leaving from this location in Reykjavik are mainly taking tourists whale watching.

The real harbor has moved to the outskirts of town. The artist doesn’t address this development directly. But it is strikingly apparent upon taking a walk outside of the museum, where generic shopping areas await customers. How do we allocate cultural significance? And what happens to a town when sites of cultural significance are relocated? This is the core question Guðnadóttir’s show asks. How does the culture industry partake in the act of making or obstructing visibility?

“One of the palettes broke, the boxes hit me and dislocated my shoulder,” Davíð goes on. He was in and out of hospitals for two years, and then realized he couldn’t go back to the job anymore. “I sometimes miss it,” he confesses. “These are tough but good guys. Now I run a comedy club,” he shrugs.