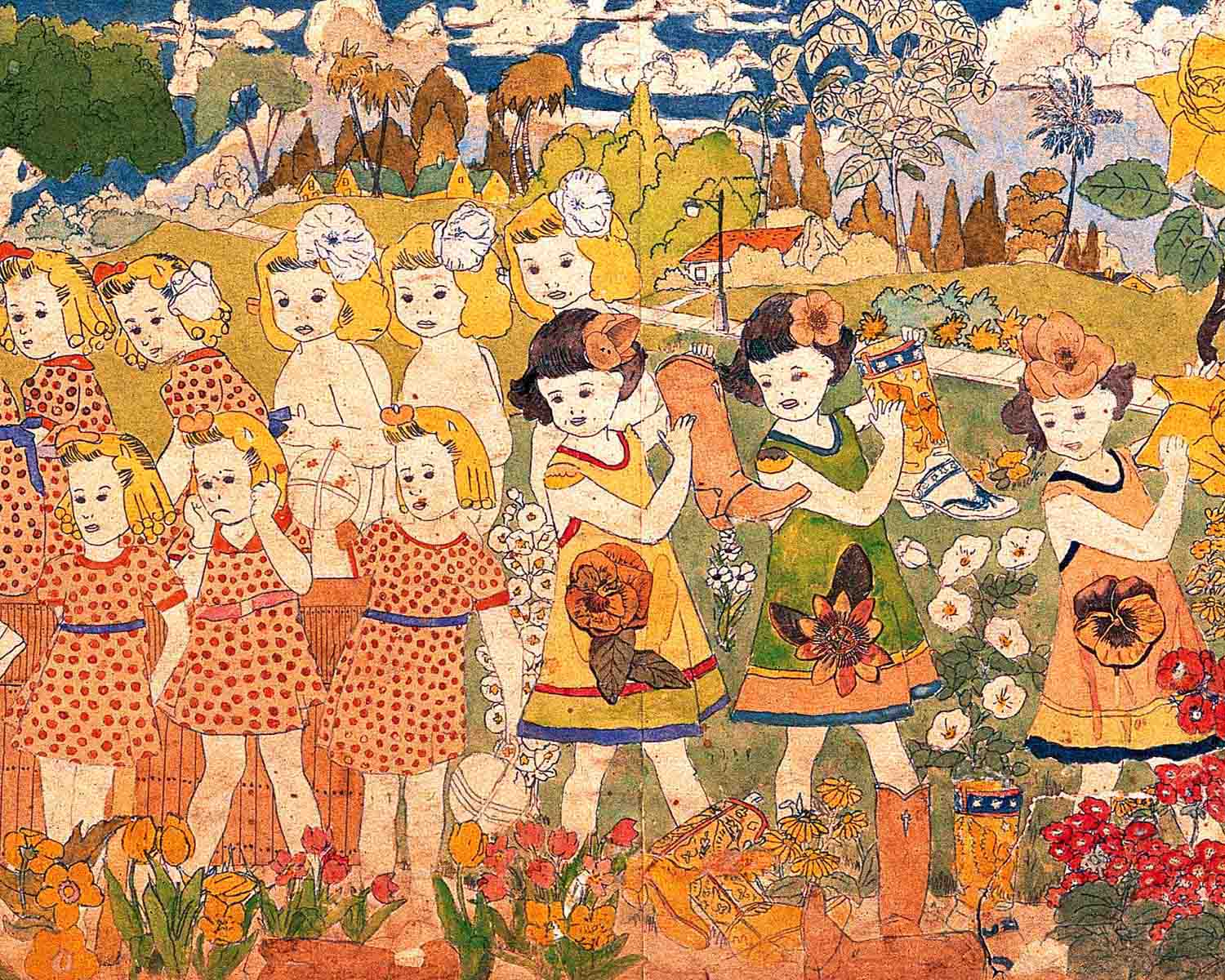

To dream is to attempt to solve a riddle that never ends — to answer a question with an ever-changing answer that is itself shaped like a question mark. Dreams are realms of constantly morphing shapes, clues, and identities that promise ever-more-esoteric keys to the mysteries of the universe. Dreaming is not about unearthing meaning from the subconscious; it is about playing with the clay of a greater meaning that overwhelms us.

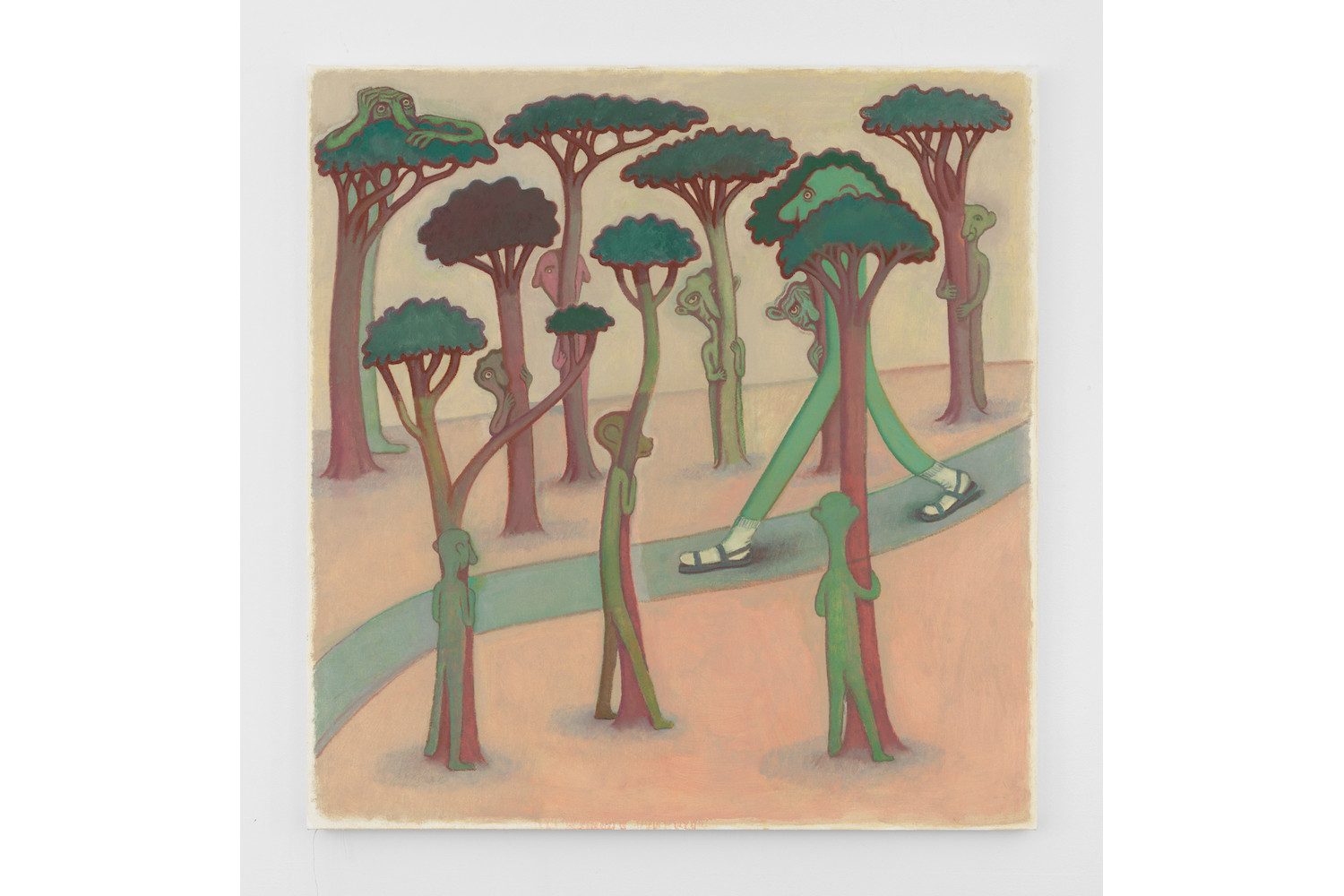

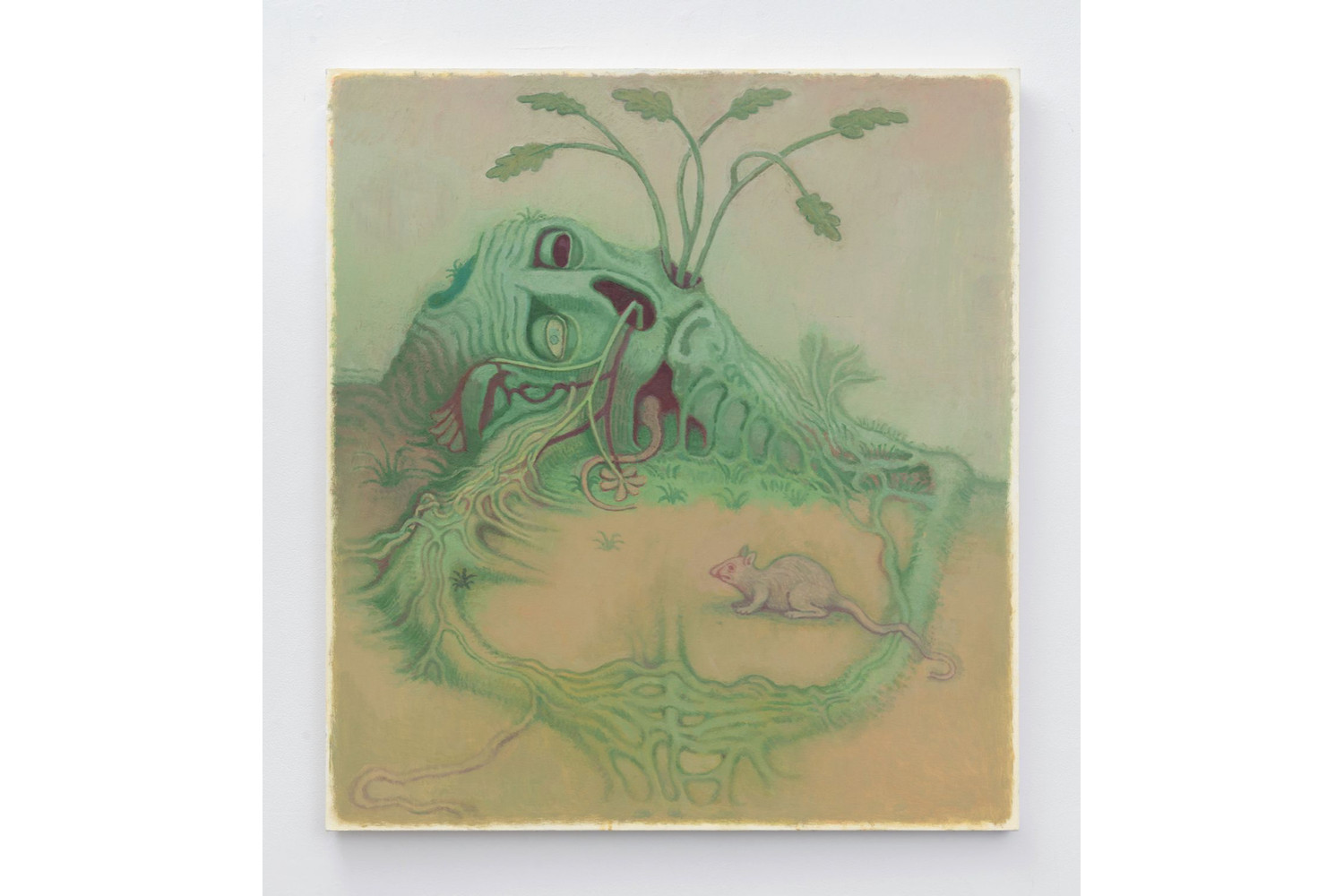

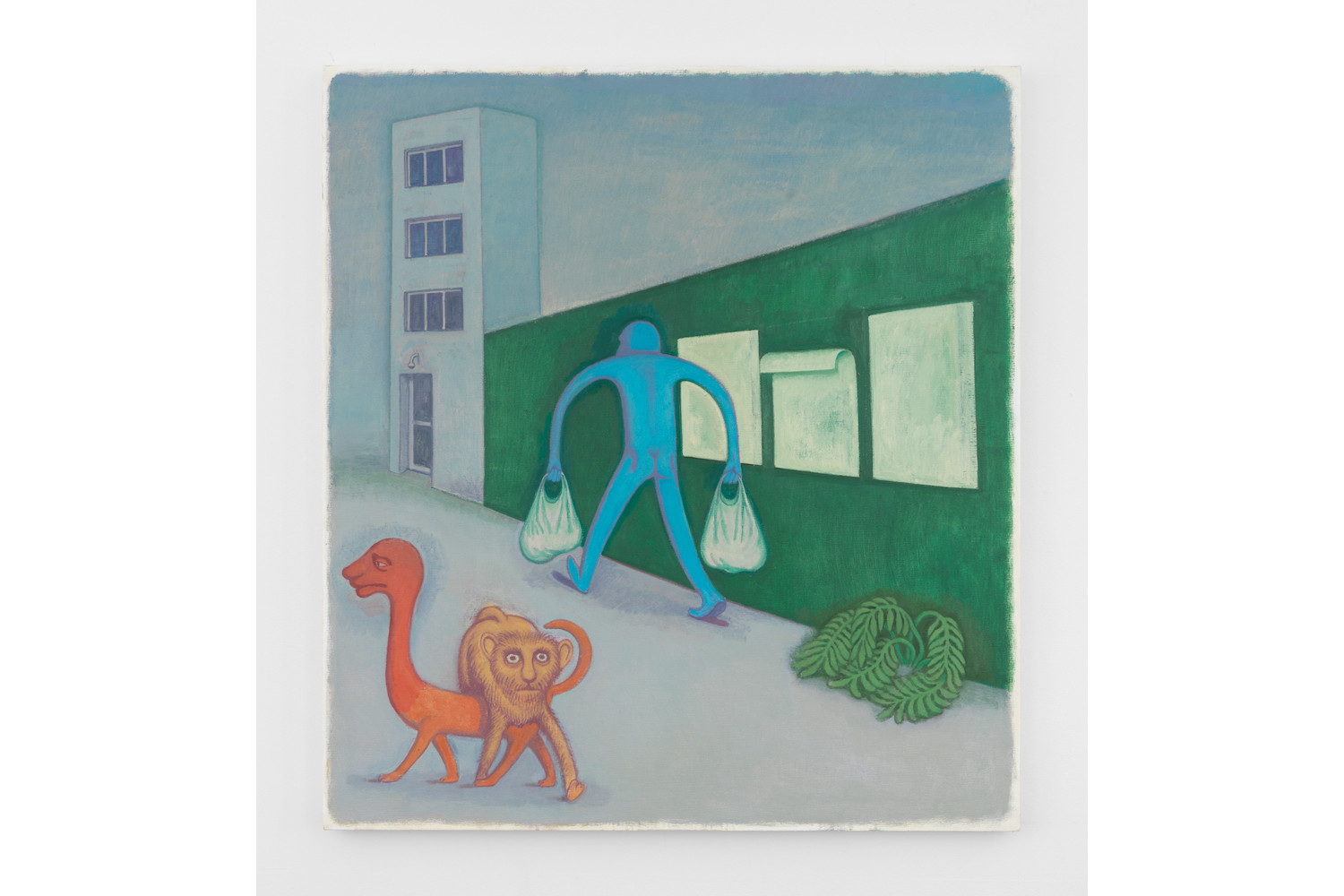

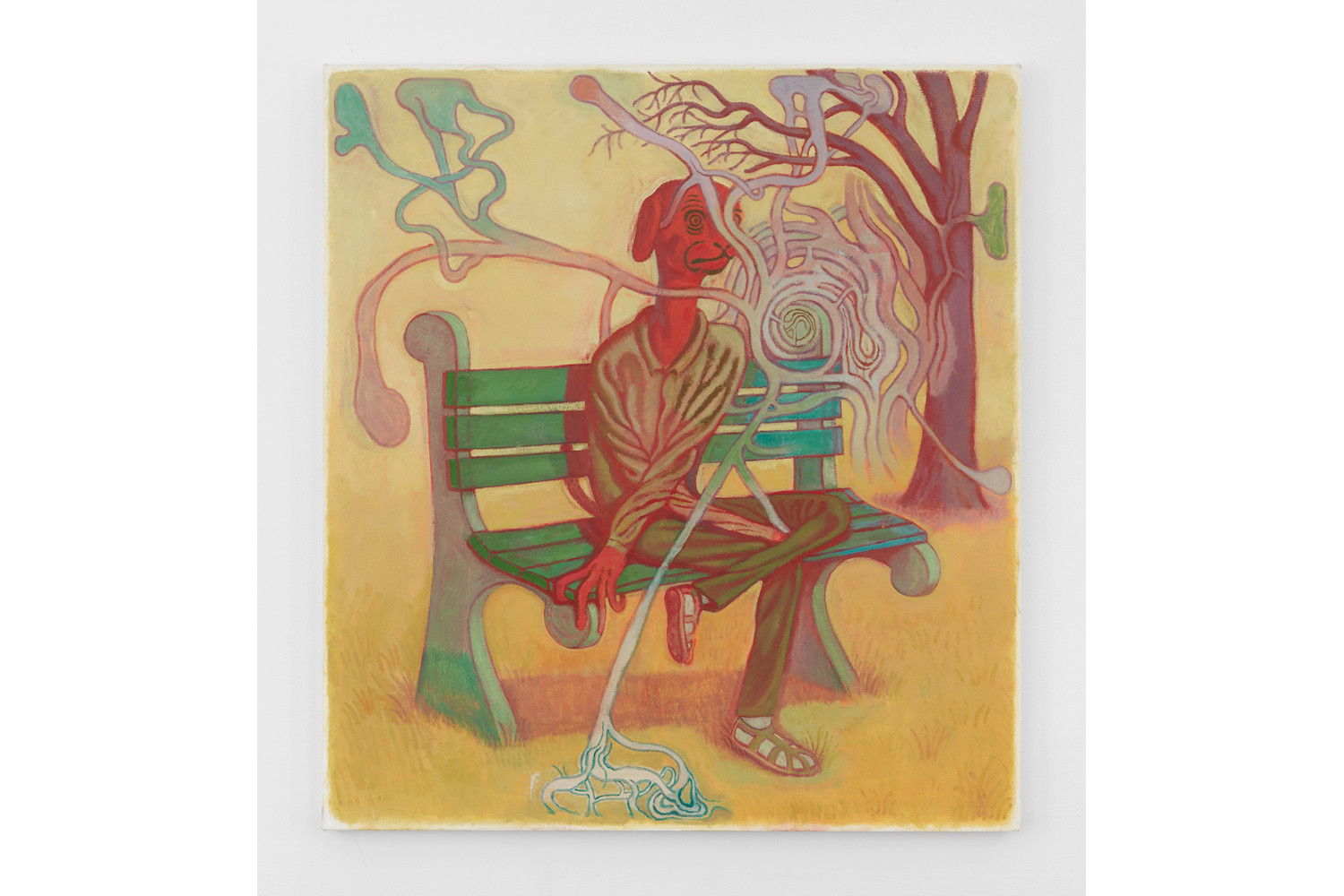

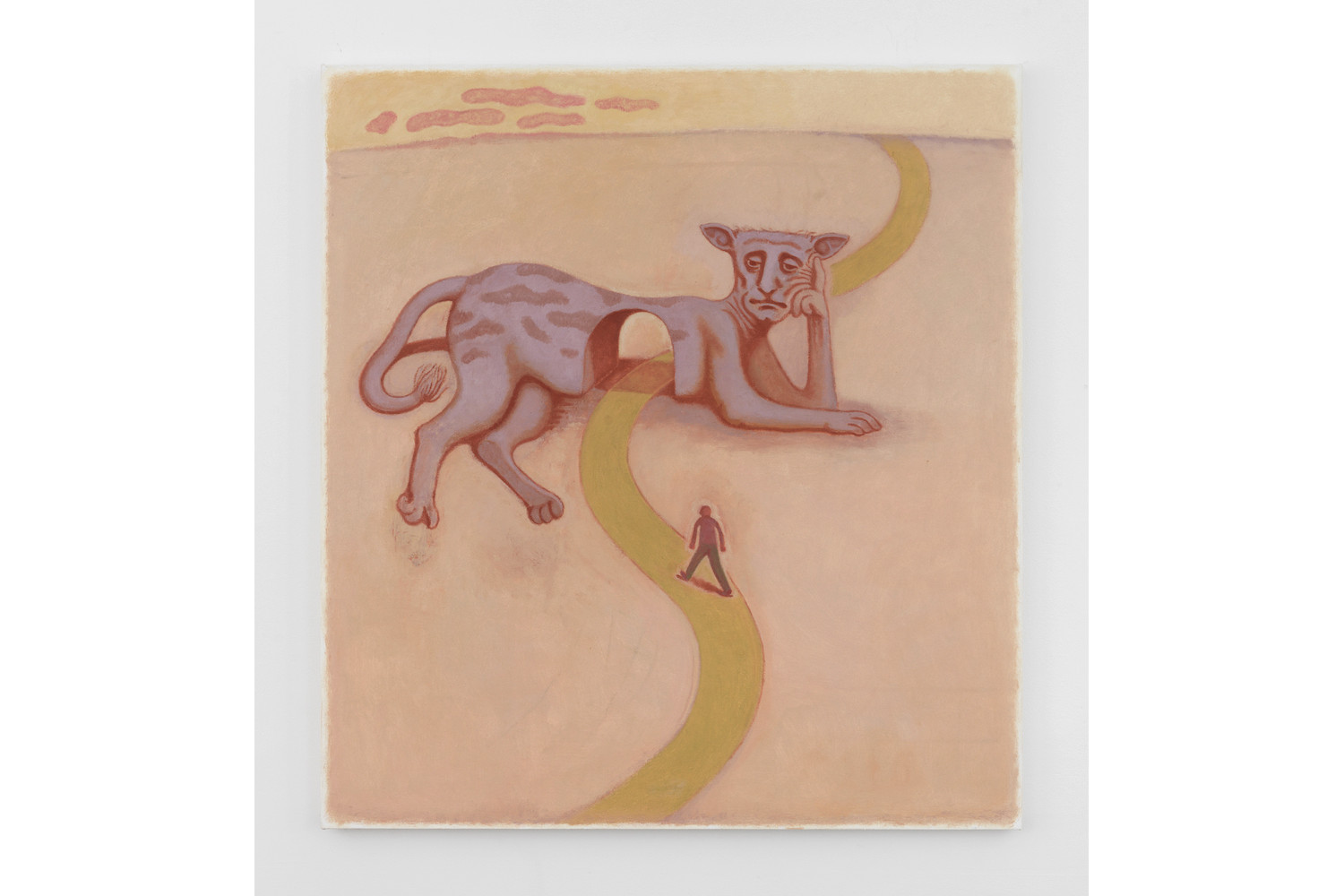

Clayton Schiff’s latest show, “Small World” at 56 Henry, explores this surrealist terrain. Schiff portrays anxious creatures that look like they’ve escaped from a Maurice Sendak picture book and are now lost or afraid, barred from their homeland. Wandering, stuck in an absurd reality with no horizon or solution, his characters seem troubled that the enchantment is gone. They silently ask: “Are we not magical anymore?” One frightened creature walks through a forest where its peers are all hiding from view (Keeping Up, all works 2020); another has waited for too long and has decayed to the point of becoming part of the ecosystem (Returned, 2020); others walk past each other as if oblivious to each other and to their banal urban setting (Crummy City, 2020). One subject seems to have been trapped by its own act of contemplation, here materialized in the form of a giant fleshy web (Connecting, 2020). Another creature, akin to a mythical sphinx, appears bored to death, having no riddle to ask but instead offering an open gate though its belly (Accommodations, 2020).

The paintings are populated by characters with eyes wide open — a seeming contradiction. Do they merely dream they are fully awake? Each scenario is ambiguous, betraying a plot point within a narrative that the viewer cannot know. Schiff’s protagonists seem hypnotized, frozen between dream and reality, meaning and absurdity, silence and scream. Some scenes are reminiscent of Giorgio de Chirico’s sun-drenched afternoons — depictions of the metaphysics of stillness, lost in the arcana of time. We’ve lost the innocence of childhood but haven’t traded it for anything better: we’re left with our toys, our childhood stories, trapped in a labyrinth of immaturity, the head charged with existential questions, and no one to help, to lend us the keys to adulthood. The sphinx doesn’t care, the forest is wary, and the animals are petrified. Everyone is blocked in his or her progression, giving in to a fear of the void. Here is a kid-friendly version of Kafka’s stories. Schiff’s paintings embody a frozen panic of the here and now: no escape, no hope, simply endless interrogations about the nature of our dreams — and no one to share them with.