A major exhibition presented by Cheim & Read and Ortuzar Projects brings together work that proved crucial to the development of Lynda Benglis’s practice during her first decade in New York. Three concurrent exhibitions will be on view in Tribeca and the Upper East Side.

Lozenge-shaped wax paintings are juxtaposed with Benglis’s latex and polyurethane pours at Cheim & Read on 23 East 67th Street. One floor above, at the Ortuzar viewing room, is a selection of gilded wall sculptures inspired by the caryatids from the porch of the Erechtheion at the Acropolis in Athens. Sparkle and metallized knot sculptures, including the multi-part installation North, South, East, West, 1976 – last shown in New York at a 1981 Whitney Museum exhibition – are on view at Ortuzar Projects on White Street in Tribeca.

Benglis has forged a fifty-year career at the forefront of Post-Minimalist innovation alongside her peers Louise Bourgeois, Richard Serra, Eva Hesse, and Bruce Nauman. She arrived at singularly beautiful, often shocking results that, as art historian and critic Julia Bryan-Wilson writes in the exhibition’s online catalogue essay, “refuse to be constrained by conventional codes around the ostensibly discrete genres of painting and sculpture.” This joint exhibition marks the first survey of Benglis’s early work in New York since her mid-career retrospective (2009-2011), which traveled to the New Museum.

Cheim & Read, 23 East 67th Street

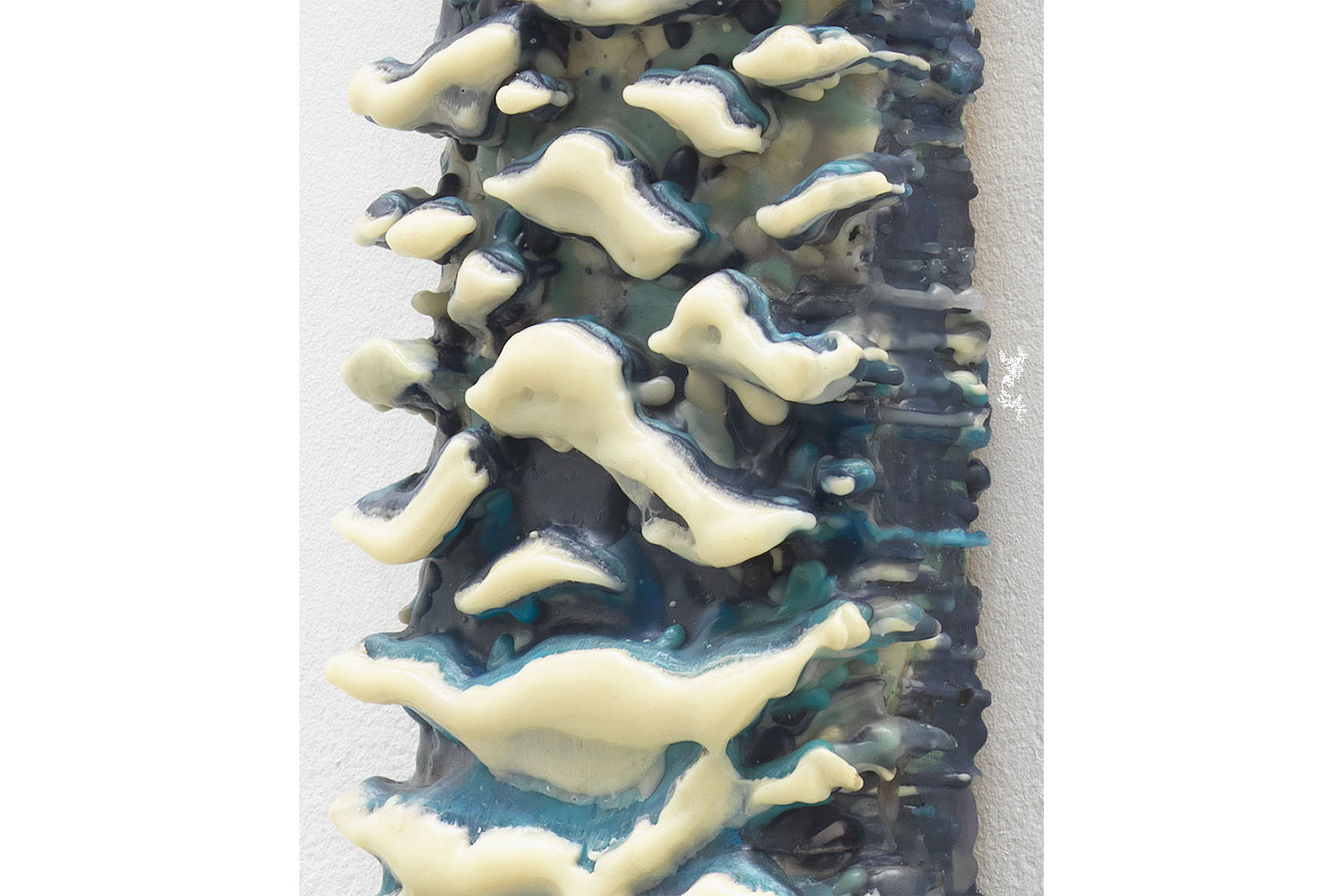

These sexually suggestive bodies of work both arise out of highly liquid processes. Made at the cusp of the 1960s and ’70s, these lushly colored, sculptural build-ups of pigmented wax transform their wood and masonite supports into ambisexual totems, alternately reveling in buttery sensuality and bristling with coral-like encrustations. Simultaneously phallic (vertical and columnar) and vulval (symmetrical and slit across the middle), the artist likened the making of them to masturbation, during which she repetitively applied coats of molten wax.

In contrast, the latex and foam pours, from 1968 and 1969, sit on the floor with impudent humor, jarring shapes, and provocative color. Benglis created them by consciously lampooning the macho Abstract Expressionist myth of the genius alone in his studio, attempting to force art history in a single direction while ignoring the multifarious visions that actually existed. The works in this show display Benglis’s insistence, as Catherine J. Morris writes in the catalogue for the exhibition WOMAN. FEMINIST AVANT-GARDE of the 1970s, that “culturally and politically determined labels should be understood as fluid and responsive positions rather than as static identifications.”

Ortuzar Projects, 23 East 67th Street

When she was a girl, Benglis’s grandmother took her on a trip to the Greek island of Megiste, also known as Kastellorizo, her family’s ancestral home. It was there that she encountered the gilded icons of the Greek Orthodox Church, which made a deep and lasting impression on her. Benglis’s use of gold is conflicted and complex, playing on its perceived preciousness as well as the ways it can be cheap and deceptive, a referential range encompassing both Byzantine treasure and Mardi Gras glitter. In her catalogue essay, Bryan-Wilson singles out the bulging, bow-like Flounce (1978) as emblematic of “the voluptuous pleasures found in femme self-fashioning of all kinds, [reveling] in its outrageous and lewd aspects.”

Ortuzar Projects, 9 White Street

Knot sculptures made out of cotton bunting treated with glitter, paint, or sprayed metals create an interior and an exterior, like a body, and reference the long limbs of a figure. The four elements, sprayed in zinc, steel, and tin that make up North South East West (1976) explode in an ecstatically choreographed configuration across the wall. In these works, Benglis exhibits a surface restraint, employing mostly monochrome, while ratcheting up the complexity of the forms. These are Minimalist sculptures gone haywire, looping into and around themselves, evoking the convolutions of lived experience rather than the purity of theoretical thought. The show also includes Smile (1974), a bronze cast of the double-headed dildo that Benglis brandished in her notorious ARTFORUM ad of November 1974, which launched the artist as an icon of defiance against the powers that be.

After moving from Louisiana to New York in 1964, Benglis began a series of radical experiments with materials and techniques in pursuit of “defiantly feminist, […] queerly, cheekily, forcefully femme” works that defy preexisting formal and material parameters of contemporary art. From the very beginning Benglis’s practice, she has manipulated ambivalent and critical relationships among formal categories, confounding the definitions of performance, photography, video, painting, and sculpture. Helen Molesworth referred to this admixture as “a radical slippage of coordinates” (2) that opens Benglis’s art to multiple streams of bodily, gendered, erotic, and psychosexual content. Together, these key bodies of work bear out Benglis’s formidable influence on contemporary sculpture. Her radical experiments with materials, engendered in style and form, must be reconsidered today as not only provocative but thoroughly transformative.