An alarm is sounding in the art world, and it’s become increasingly deafening. The wails of this siren are not limited to the art world alone; creative classes of all varieties — in fact, all of those capriciously deemed “nonessential” by the powers that be — are having the precarity of their occupations cast into ever-starker relief. Meanwhile, foundational behemoths flounder into mere pockmarks on the face of the cultural landscape — vestiges of something past. Yet the art world’s panic has been felt with painful, if not unique, acuity; in an industry already notorious for its fiscal paucity, the collective tightening of purse strings has resulted in seismic shifts.

Just this month, Anne Pasternak, director of the Brooklyn Museum, announced that the institution’s endowment lost an astonishing nineteen million dollars through the markets’ steep and rapid decline, without counting an additional four million in lost income from visitors. 1 In the private sphere, Gagosian has announced that they are furloughing all part-time staff and interns, while instituting pay cuts across the board for their full-time employees — pay already defined by its insufficiency in major cultural capitals. 2 If these measures reflect the realities of the (relatively) flush, it has become a tacitly understood fact that many smaller iterations, public and private alike, have ceased to exist at all.

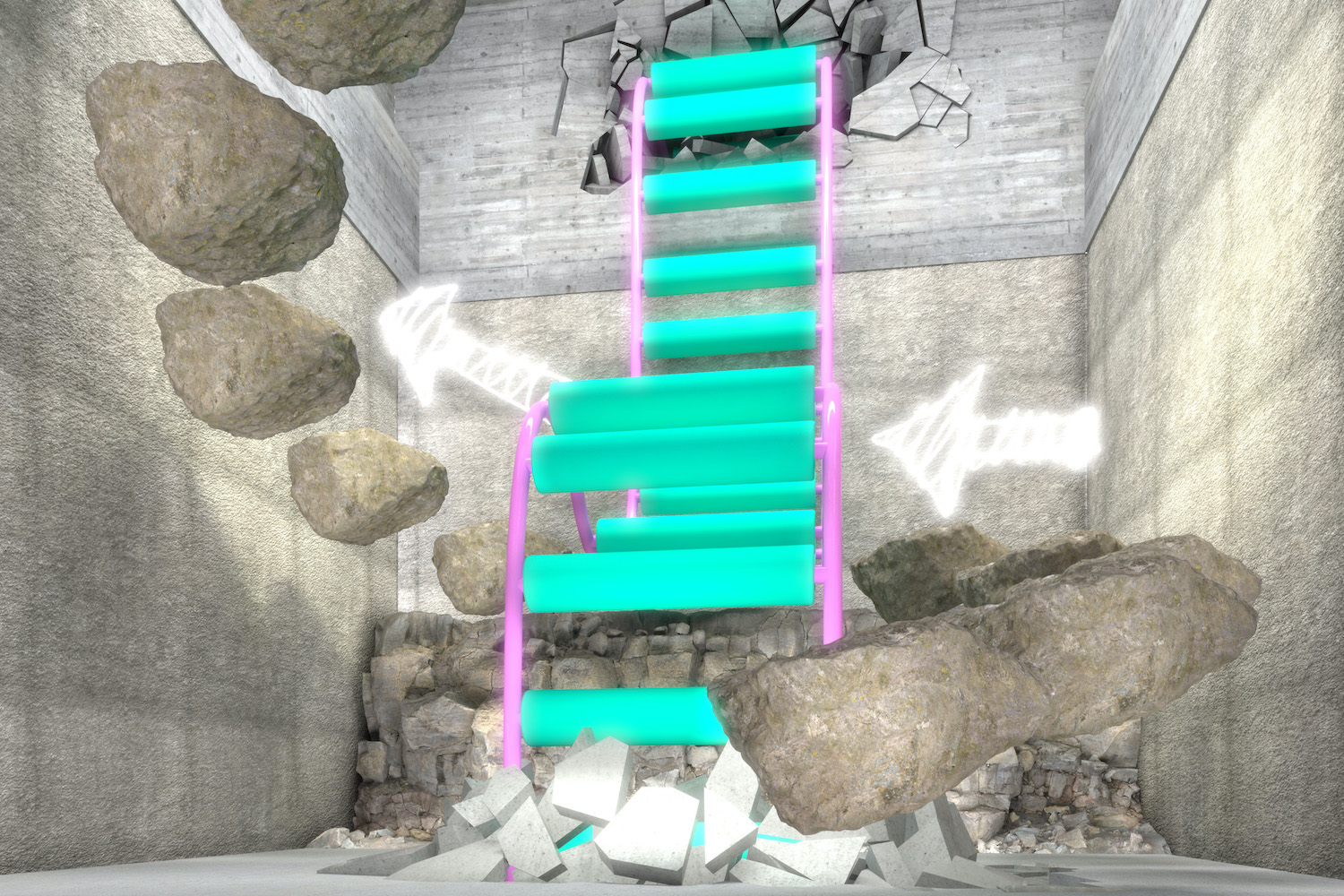

In turn, these closures trickle down to practitioners themselves. At best, those previously able to produce full time have seen shows postponed, if not cancelled altogether, bearing the inevitable effects on income that follow an inability to sell one’s work. Worse, those on the precipice of professionalism — those who often supplement artistic production within the gig economy — have been doubly cast into ontological crises. Without the opportunity to show in galleries, an artist’s career growth may well stagnate; but, more fundamentally, as “gigs” milked for sustenance dissipate, many artists will be less able to afford art supplies at all. In this sense, the crisis compounds; fewer materials results in fewer pieces, leading to fewer sales, and the perpetuation of a viciously cyclical — and markedly tragic — decline in artistic capital.

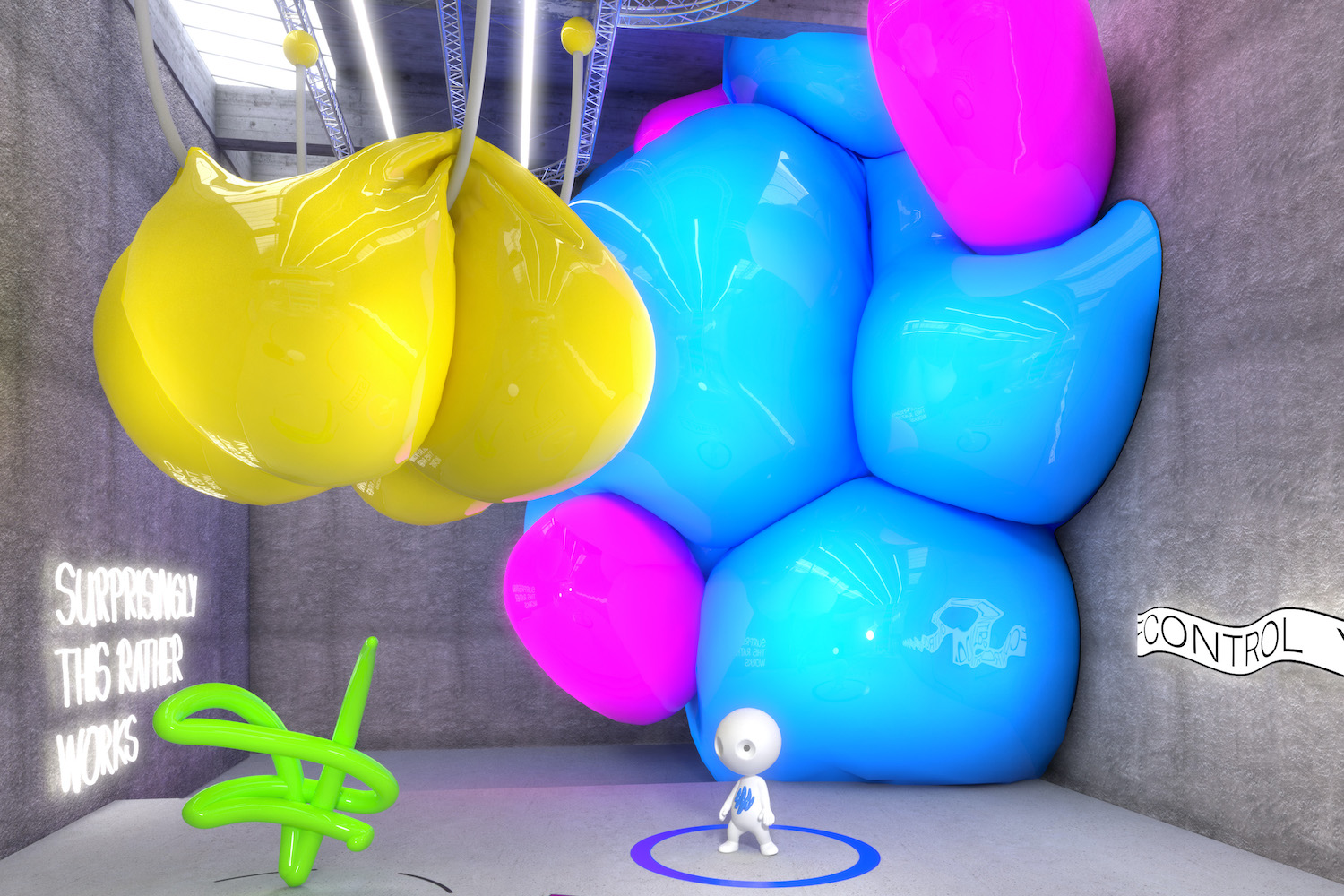

This has, in turn, necessitated an industrial movement toward a greater online presence for all, and, for most, a greater Instagram presence in particular. Countless galleries have migrated (if not entirely rearticulated) shows to online viewing rooms in an attempt to mitigate the effects of COVID closures, while museums have provided greater online accessibility to their collections. For those who lack the means to create visually lavish online suites for their slate, Instagram has become of vital importance — the ability to exhibit and promote at negligible cost while most traditional revenue streams continue to dry up has proven to be a much-needed lifeline. Similarly, even artists not due to exhibit have continued to be able to reach expanding audiences in hope of finding patrons outside of the gallery system. This, no doubt, has mitigated the potential for an immediate and long-lasting downturn.

But, as Instagram quickly achieves primacy in the exhibition world, its functionality remains disturbingly ill-suited to the art market’s need for sustainable growth and reach.

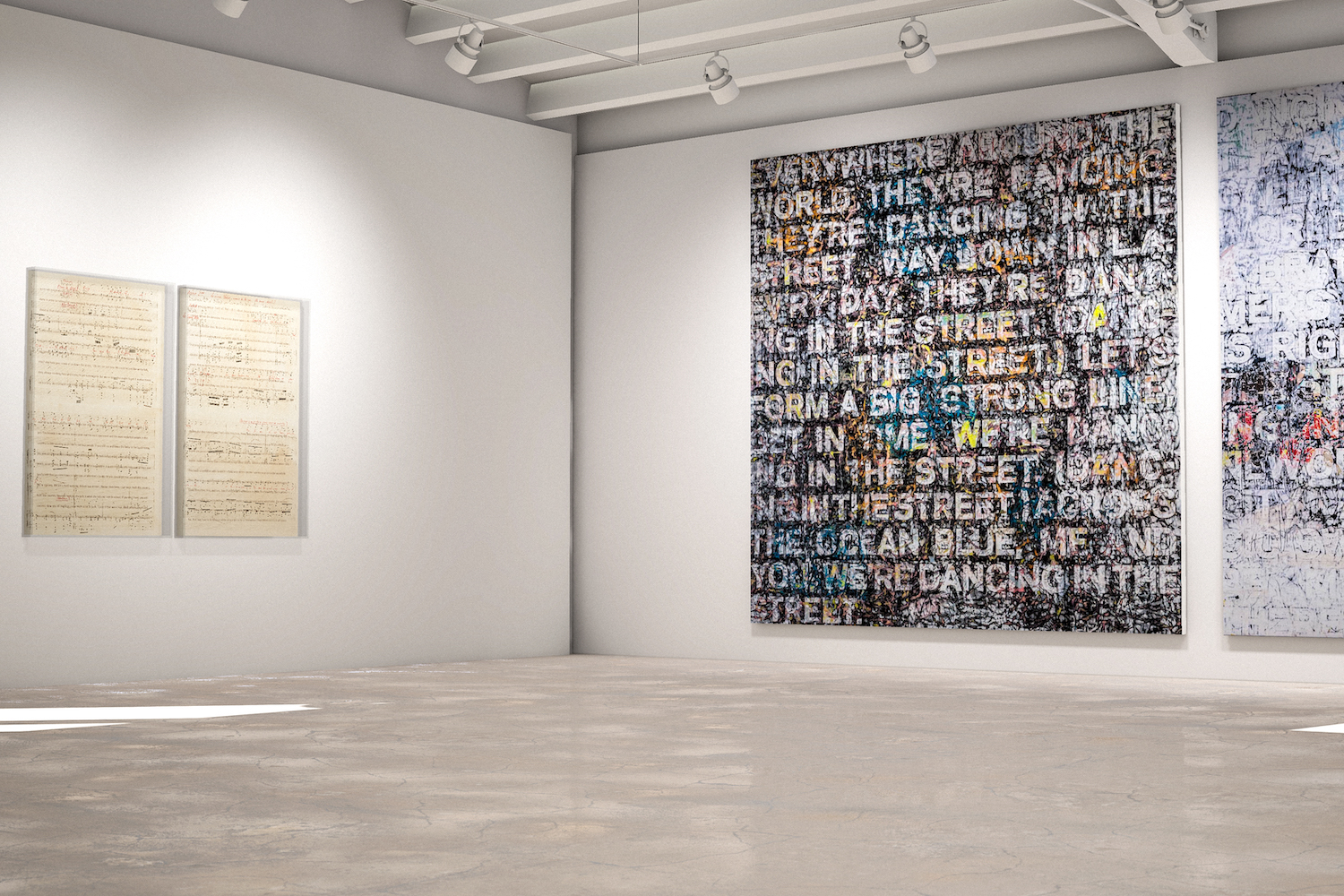

Artists’ use of Instagram as a professional tool is far from a new phenomenon, and a thriving gallery system can serve to underscore how both can work in concert. Those who have yet to find representation are able to broadcast their practices to burgeoning markets, while galleries are able both to maintain consistent relationships with their clientele and scout an ever-emerging batch of producers. In this vein, galleries continue to exist as institutions because they provide services fundamentally anathema to Instagram’s platform: they are able to communicate (a degree of) artistic value with their own allocation of resources, while providing revenue sources instrumental to the industry — collectors, public institutions, even simply habitual buyers — with personable and professional (read: catered) means of creating and maintaining markets. One ought not forget that art economically behaves much as a commodity; artists and their work command a market, with values dictated by broader mercantile behaviors.

At the risk of sounding pedestrian, a simple analogy is the relationship between an established organic grocer and the local corner fruit stand: one may, of course, be able to find delicious, cheaper produce hawked by independent stalls, but grocers continue to exist because they can guarantee a minimum quality within a range of market-standard prices (no matter how smug or otherwise elitist they — and their facetiously named “traders” — may be). At its best, the system works symbiotically — artists are able to create interest around their own work by utilizing social media platforms, while galleries are able to develop, concentrate, and maintain select groups who stand to make artists’ practices sustainable.

However, a collective movement toward online platforms has thrown this system into dissolution, to the immediate disadvantage of galleries and to the long-term disadvantage of artists. In an attempt to find fast cash, artists have taken to selling their own work outside of their representation, allowing poised collectors to undercut preexisting market rates and avoid fees otherwise resultant from added middlemen. This is partly due to the lack of specificity inherent to commercial galleries: forced to cater to their entire roster and reflect current holdings, galleries remain beholden to a multiplicity, while individual artists can make available and broadcast their work at much higher volume. But this is also the result of the platform’s structure itself: unable to curate the events and experiences that give the gallery value in the marketplace, they are left to contend with a cacophony of memes, pets, Instagram models, and acai bowls.

In the immediate sense, this benefits artists. Able to sell their work at high margins and create (hopefully) long-standing connections with buyers, they are ostensibly able to leapfrog institutional impediments to the sale of their work. However, the ideal iteration of this transaction is but a shadow of the reality for most: eager to find instant sources of cash, artists sell work well below its extant market value, wreaking long-term havoc as they look to build viable careers. Undercutting markets that have been stabilized within the gallery system, coherent bodies of work — and their relative scarcity — fracture, thus fragmenting growth trajectories that stand to benefit building careers in the long term. Expressed pragmatically, once normality is again established — or more likely, a new normal is instituted — what kind of collector is going to pay what was formerly market rate for an artist’s work they got at a fraction of that price less than a year ago? A collective sense of goodwill is little more than a pipedream, and certainly not contiguous with the capitalist-forward buying strategies of the collecting elite.

In order to mitigate this, Instagram as a platform must take greater responsibility for the position into which it has now been cast, allowing functionality for galleries to better serve their roles in a virtual climate. Unable to host physical viewings to affirm the value of work, galleries must be able to sufficiently leverage their communal authority while having recourse to the most basic of consumer institutions — private posts in lieu of viewings, and multiparty, private livestreams to simulate the back and forth of discussion over an artwork, along with the ability to better express the spatiality of a piece. While far from perfect, an increased capacity to allow the system to function as it otherwise would stands to institute a normalcy that is far more sustainable than current conditions.

We know this to be far from a technological fantasy; Snapchat has allowed private, paid accounts for several years, all without the programming power of Facebook behind it. No doubt, galleries compose but a sliver of Instagram’s user base, but with the weight of an industry thoroughly on its back, the platform has a responsibility to adapt user experience, particularly when such changes stand to affect the average poster so little.

In a present currently defined by governmental inaction, undignified death, and looming societal uncertainty, one can be forgiven for not thinking of the plight of artists. However, as we inch our way back toward a world that resembles the one we so frantically left only months ago, ensuring that cultural practices can continue relatively unfettered is becoming of increasing importance. It is with a mind toward this that such action by platforms like Instagram take on a much larger meaning; subtle changes stand to reinforce the bedrock of an industry that otherwise threatens to collapse during such uncertain times.