“Listening In” is a column dedicated to sound, music, and listening practices in contemporary art and its spaces. This section focuses on how listening practices are being investigated and reconfigured by artists working across disciplines in the twenty-first century.

Lamin Fofana and Jim C. Nedd have been collaborating since the release of Brancusi Sculpting Beyoncé (2018). The recent trilogy of works discussed below were composed by Fofana and accompanied by a series of photographs created by Nedd between 2018 and 2019.

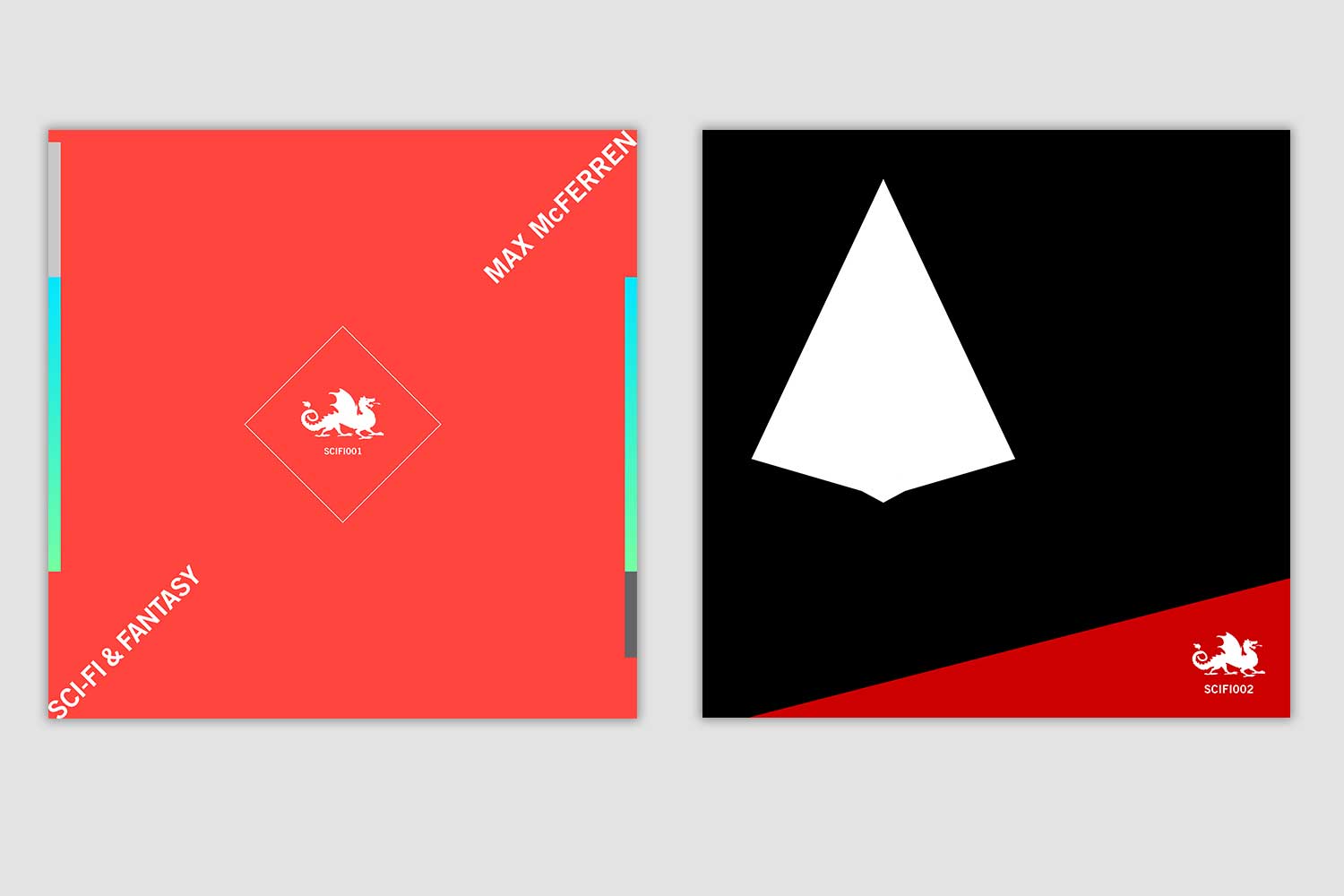

Jim C. Nedd: My first encounter with your work takes me back to the beginning of the past decade with your record label Sci-Fi & Fantasy. The 2010s were a very specific moment in music — what was the context back then?

Lamin Fofana: Around 2010 I released a couple of EPs on Dutty Artz, a truly wild, rhizomatic, and outward looking collective and imprint founded by Jace Clayton, otherwise known as DJ /rupture, and Matt Shadetek. The collective put together events, mainly parties in New York, but musically it was scattered across the globe, with connections in London, Berlin, Rio, Mexico City, Kingston, Abidjan, and Cape Town. At a certain point, the collective stagnated and began to cool down. I wanted to start something fresh. I was reading a lot of science fiction — Samuel R. Delany and Octavia E. Butler, but also Nalo Hopkinson, Lauren Beukes, Kim Stanley Robinson. I wanted to explore the themes and ideas from the stories. So I started my own imprint with my friend Paul Lee. Sci-Fi & Fantasy was really in action between 2012 and 2014. We released a handful of club twelve-inches and ambient projects. In New York I was surrounded by friends in different scenes making interesting music. There were a lot of micro genres in the early 2010s, and that was a bit annoying but it was also a great period for those of us endlessly searching for wild electronic music.

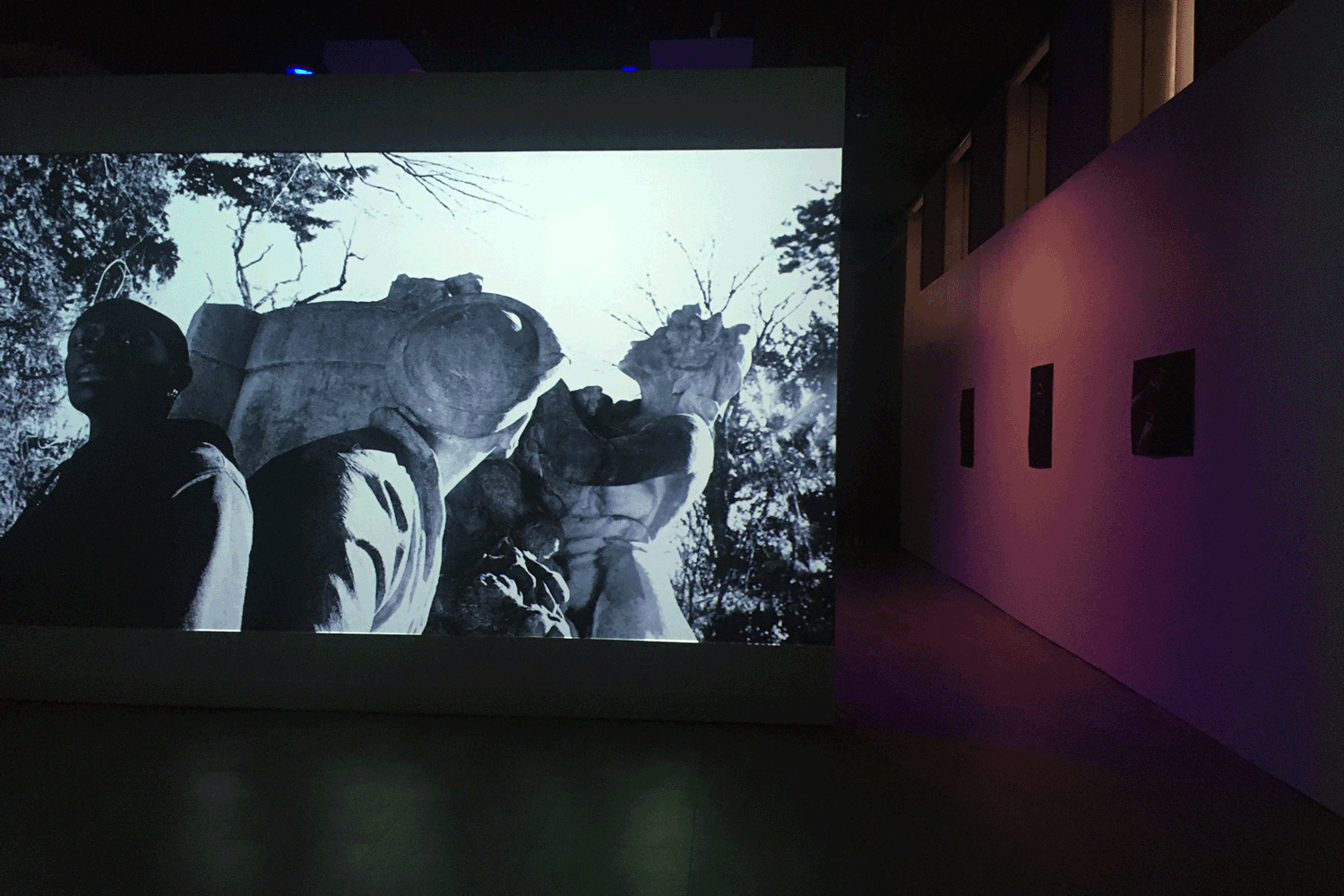

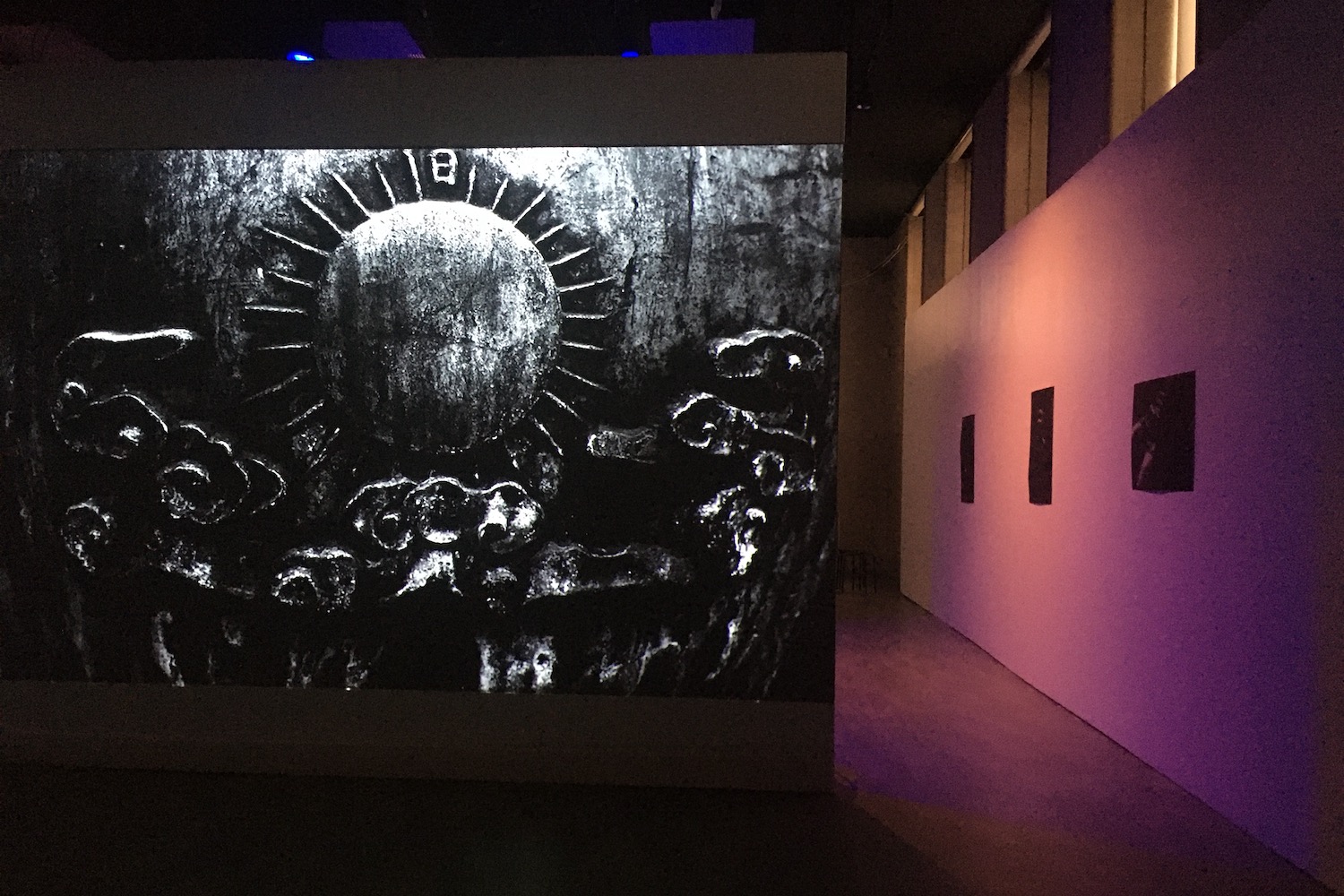

JCN: Your latest exhibition, “BLUES,” at the Mishkin Gallery in New York City, marks a new approach in your practice. How did this new body of work come about?

LF: “BLUES” came about during a period of intense engagement with foundational texts by Sylvia Wynter, W. E. B. Du Bois, and Amiri Baraka. In the midst of this engagement, a body of sound works emerged in the form of three albums: Black Metamorphosis, Darkwater, and Blues. Black Metamorphosis is Wynter’s nine-hundred-plus-page unpublished manuscript written in the 1970s and arguably one the most important interpretations of the black experience in the Western hemisphere. Du Bois’s Darkwater, published exactly one hundred years ago, is a series of essays, poems, and sketches reflecting on white supremacy, settler colonialism, racial capitalism, patriarchy, beauty, democracy, and more. Blues reflects on Amiri Baraka’s Blues People (1963), a book about the experience of making a culture in an alien world. I developed a practice of transmuting text into sound. Our first collaboration, Brancusi Sculpting Beyoncé (which came out in 2018 on Simone Trabucchi’s Hundebiss imprint) was the spark, but in a way I have been creating works dealing with blackness and displacement for a while. In the middle of realizing this project, I invited you and Nicolas Premier to contribute images and visuals because of our previous collaborations and individual conversations around blackness, migration, and the turbulent times we are in. Our collaborations yielded unexpected and harmonious connections. Alaina Claire Feldman, curator and director at Mishkin Gallery, offered unconditional support for the exhibition.

“BLUES” is also a very scattered project linking three continents, Africa, Europe, and the Caribbean (South America). It deals with contemporary black life, the environment, migration, and the past and future. The work of Sylvia Wynter, and important contemporary writers like Fred Moten, Saidiya Hartman, and Christina Sharpe, has been very insightful at a time when the world can no longer be explained by orthodox thinking. What will happen to us after this pandemic? With what are we entering that new world? Can we imagine another world, a different existence?

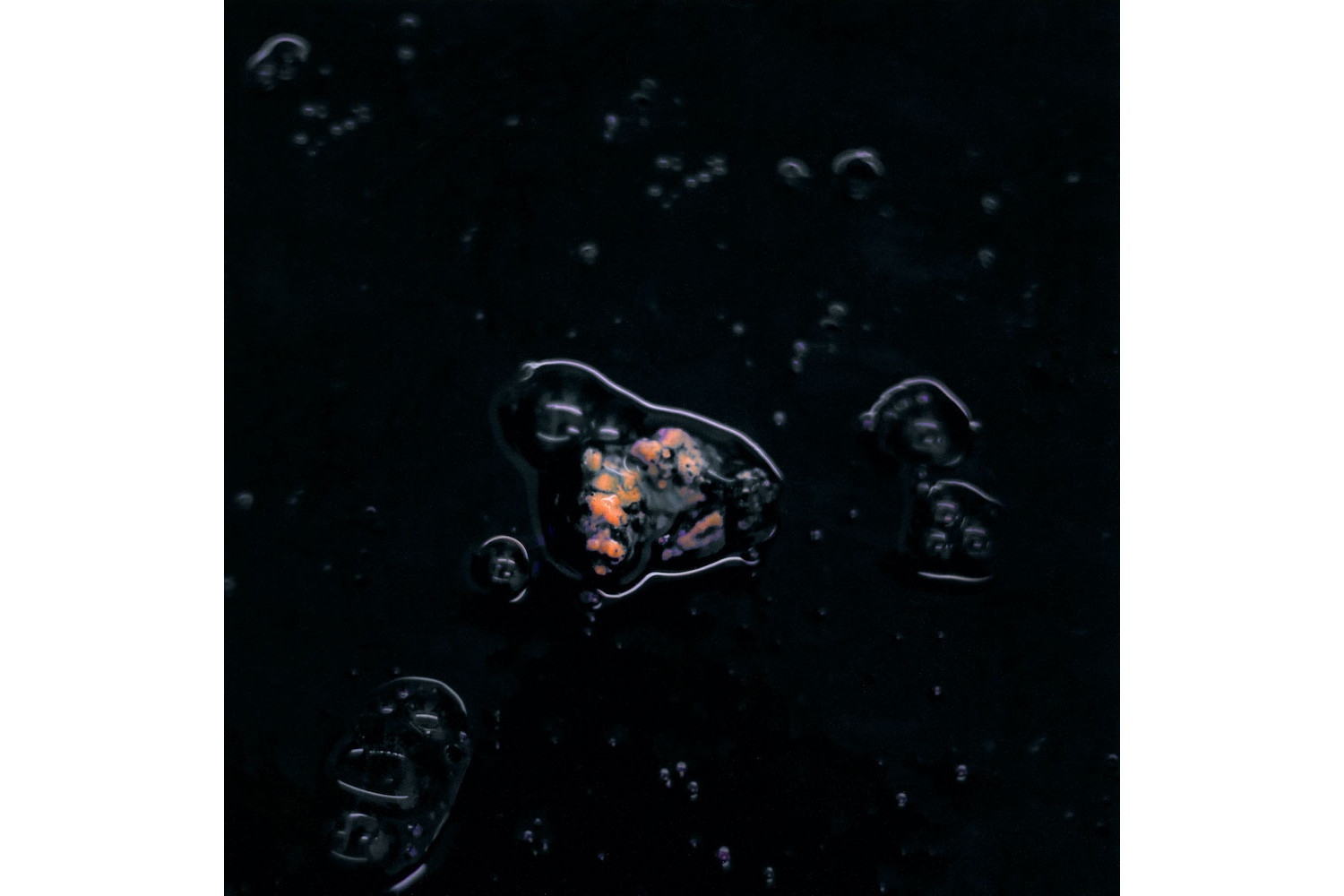

JCN: When I heard your live set, I was captured by a dense aquatic feeling. I was instantly immersed in a sort of “multi consciousness” of your work: the field recordings, beats, and voices all interacted narratively in such a way that the performance felt like chapters of a story. What motivates this narrative approach?

LF: I developed an interest, a level of awareness of the oceanic and the idea of geographical displacement early on. In a live context, there are always multiple narratives or structures moving. I’m very much interested in utilizing the physicality of sound to transform spaces, to disorient, or to create a space for reflection on displacement, solidarity, isolation, or whatever the mood or feeling we may be dealing with at the time. In the studio, there’s usually an underlying theme or idea with some emotion or gravity, and to be honest I don’t always know where it’s going to go. A lot of experimentation happens when I’m in production, and yeah, like you said, with field recording, archival recordings, synthesizers, and effects.

Currently, most of my work revolves around black noise, noir noir. I’m interested in music not merely about music, but music as a tool to explore ideas, opening up new dimensions and portals to new possibilities and ways of seeing. I work with archival recordings not only because of their aesthetic appeal but because they help access ecstatic time, or at the very least help in the breaking up of linearity and the opening up of nonlinear and multidimensional timescapes.

JCN: Something that caught my attention during some of your shows was the use of human-scale mirrors. What is their significance?

LF: In some settings, I prefer performing behind four to six large standing mirrors positioned so they are facing the audience. As a black person performing musical labor in front of a predominantly white audience, you have to think about these things — what Saidiya Hartman calls “hypervisibility,” or “the idea of looking and being looked at, spectacle and spectatorship, enjoyment and being enjoyed.” You know the relationship or context is strange. If you’re already in a strange land, why not make it stranger?

JCN: From the first part of your latest trilogy, Black Metamorphosis, I sensed a new way of using sound, with more time between events, or a large space for reflection.

LF: I like the idea of collapsing time and space in my productions. I’m not into the way sound is presented in most galleries and museums, and my work is naturally against the standard and typical forms. So when I enter those spaces, to install work or to perform, I have to listen closely to things. In galleries, I have been able to stretch time, expand ideas, and have my work spiral out in ways not possible in the club.

JCN: In recent years your work as a musician has highlighted displacement and migration. What brought you to these themes?

LF: I relocated from the US to Germany in 2016. I spent the last few years living in Berlin and traveling around Europe. As a black person existing and moving in predominantly white spaces, you are under continuous scrutiny and harassment by strangers. But that is part of a system, a structure of domination and subjection that is part of the human condition as we’ve come to know it — but we have to imagine the end of the human condition, especially at a time like this when we are compelled to rethink our relationships, with each other and with the planet. We have to rethink everything.

JCN: Since we began our collaboration with Brancusi Sculpting Beyoncé in 2018, mutation has always been a central topic in our conversations — mutation as a consequence of displacement. Can you say more about this topic?

LF: Well, the question was posed by writers like Wynter, Baraka, Du Bois, and Frantz Fanon. What happens when black people find themselves in the West? This process of aesthetic permutation has been going on for centuries. There has been an unbroken continuity between slavery and colonialism and contemporary antiblackness around the world. Our experience of alienation is not completely original, because we are linked to people who have been subjected to structures of dehumanization for centuries. Given this experience — because that’s what it is, it is not just historical memory — our encounters with the world compel us to experiment and create new concepts that will help us imagine a different existence.