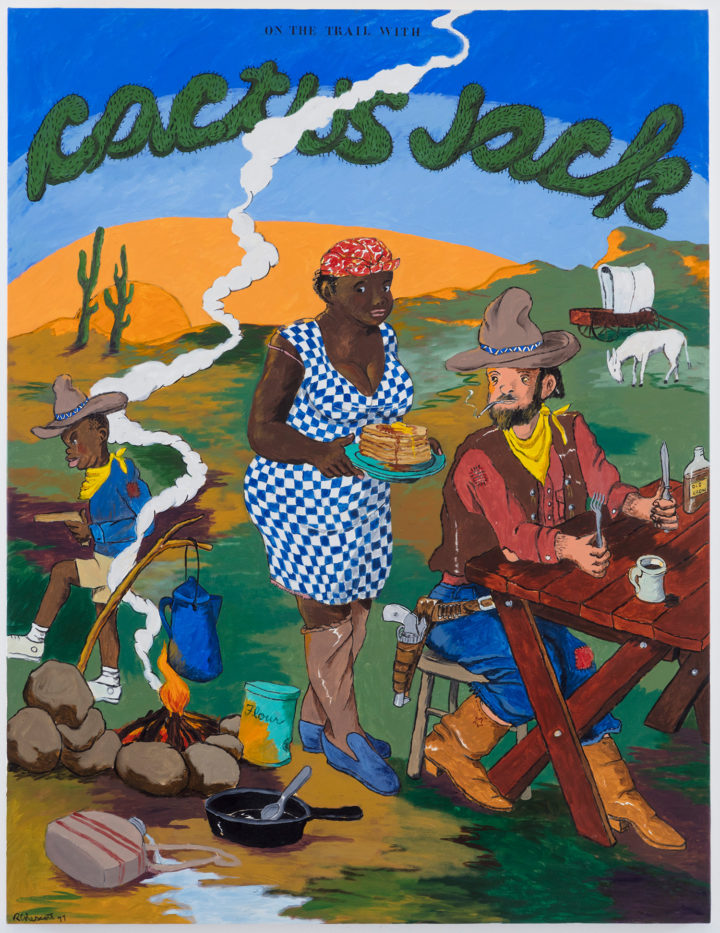

In a politically correct culture, it’s liberating and unnerving to step into Robert Colescott’s exhibition at Blum and Poe, where the late painter revels in representations of stereotypes. As an African American growing up in 1930s Oakland, popular black tropes of the time period are a mainstay in the artist’s paintings, but he doesn’t stop at black stereotypes; risqué depictions of gender issues, sexuality, race, economics, and politics abound. Colescott once described the experience of looking at one of his pieces as “a pleasure” at first, and then it’s “a problem.”

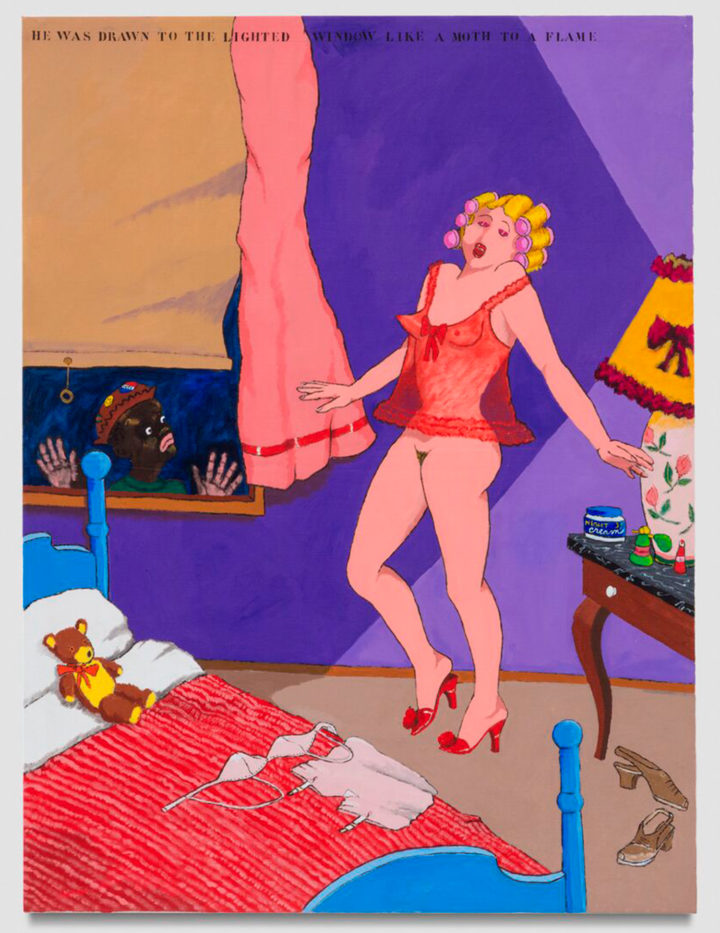

The pleasure comes forth through the artist’s skillful painterly touch, Ken Price-y color palate, and flair for comic figuration. However, the satirical read in many of the works is where problems arise. Most of the works involve only one black character, and as that character’s role interchanges throughout, we see Colescott musing on various power dynamics. In Peeping Tom (1973), a white woman stands in feigned horror in a sheer lingerie top and curlers. A black man looks on from outside through the curtains, palms pressed to the window. His “Jughead” crown and downturned lips, painted as in blackface, oddly give the perpetrator a sense of innocence. A text at the top of the painting reads, “He was drawn to the lighted window like a moth to a flame.” By equating this curious simpleton to a moth, Colescott usurps him of agency, even as he stares on at his pantless muse.

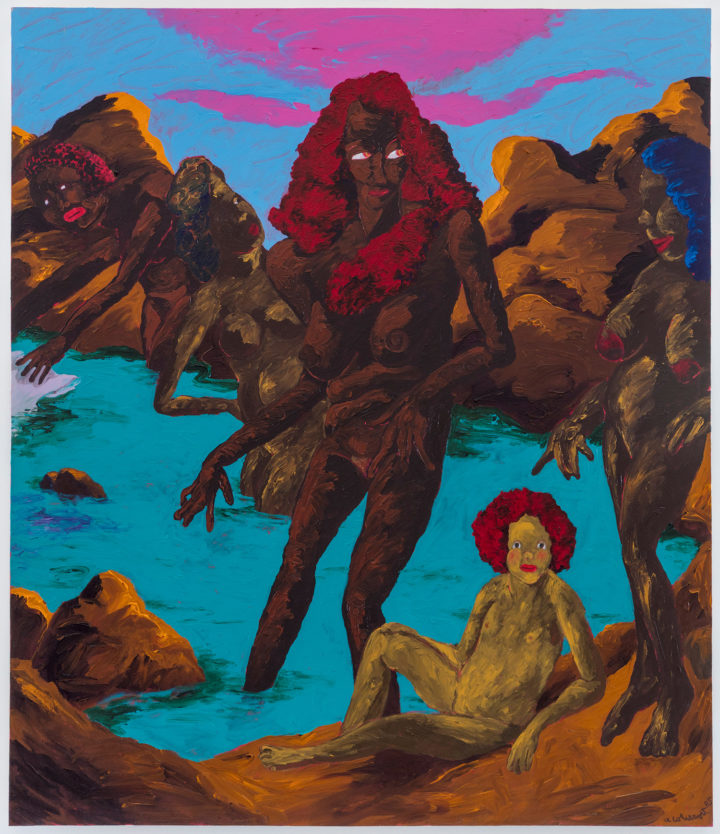

The mood changes slightly in the next gallery, which hosts a selection from the “Bathers’ Pool” series (1984–1986). With an underlayer of deep red paint, Colescott loosens his grip and allows the glowing figures to elongate in brushy layers of acrylic. No doubt pulling from the many art historical paintings of bathers, namely Cézanne, Colescott flips the racial ratio. Where elsewhere his paintings feature one black character, at the bathing pool a single white character is usually standing vulnerably in the background, surrounded by a sea of languid black figures. The dark rocks mimic the bathers’ bodies in form and color, creating an organic merging of body and earth, while the white characters pop out awkwardly and abruptly.

Upstairs, a large selection of drawings allows for deeper insight into Colescott’s process. Many drawings are presented in duplicate, with various characters swapping race or sex in each iteration. The scantly clad French secretary suddenly becomes a fuller-bodied black woman. Our Peeping Tom becomes a strong Latino character actually climbing through the window. Colescott’s magic comes through his sly touch: like a deck of cards, he throws out a bunch of characters in a variety of roles, genders, and power positions, and leaves it to the viewer to wade through the resulting situation. Ultimately, the work calls upon centuries of inequality, and in turn reflects our own personal biases back onto ourselves. Without saying anything, Colescott’s work says everything.