Amy Lien & Enzo Camacho’s ongoing collaborative practice manifests as a never-easy aggregation of images of globality: its flows and currents, of aesthetics and of capital, however displaced and indecipherable they may appear. Their most recent show at 47 Canal approaches one of the newer frontiers of digital labor, the world of Chinese e-commerce, also known as Taobao — which in the last decade and a half has reversed parts of the country’s rapid rural migration by forming entire villages and towns of rural residents spontaneously engaging in e-commerce trade. Titled Mother Holding Taobao Child, their exhibition focuses specifically on China’s recent booming baby culture, caused by a rapid rise in birthrates since 2015. Within the digital sphere of e-com, this changing demographic has caused a new commodification of both parent- and childhood.

Their seven-minute single-channel video of the same name goes “behind the scenes” of this industry, documenting the eerie choreography of simultaneous play and discipline at a children’s shoot in a Taobao photo studio. The photographer — who we learn is also the father of one of the two toddlers — gently tries to capture a believable performance of play around specific pieces of merchandise, assisted by the children’s doting mothers, who variously instruct them to smile, keep still, stand up, or hold a bag. Overlaid is scattered footage of children’s play in brightly lit Chinese shopping malls, pixilated e-com tutorials, and close-ups of post-production digital editing suites.

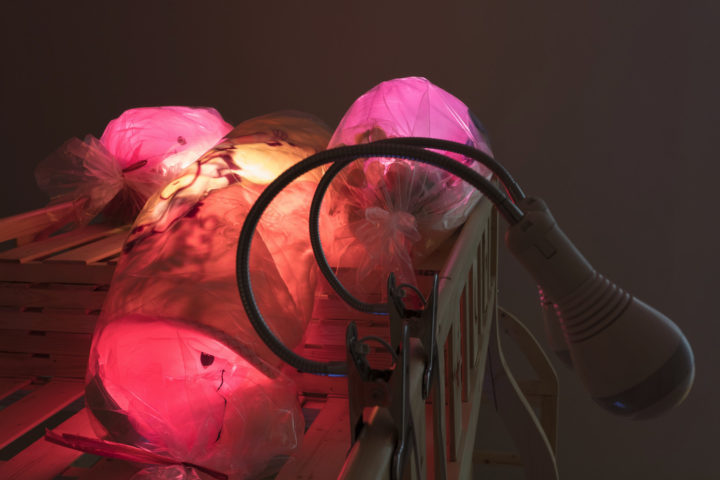

The four sculptural entities that make up the remainder of the exhibition give further form to these new sites of post-Fordist work, where social relations are subject to a simultaneous process of commodification and consumption. A “mother-child bed” — an instant Taobao classic, essentially a flat-pack wooden bunk bed reminiscent of Ikea furniture, with space for both parent and offspring — is transformed into an uncanny multimedia installation equipped with a 360-degree WIFI camera hidden within a nondescript light bulb, projecting its warped, sphere-like image back onto the bed’s rice paper bedding, while plastic-wrapped inflatable dolphins, Chinese snack items, and security blankets occupy the upper bunk. In three additional sculptural pieces, this structure is repeatedly deconstructed and wrongly assembled, turning it into nonsensical interior abstractions.

The treatment by Lien and Camacho is both strange and estranging. Armed with the critical vocabulary of the West, they approach Taobao as a kind of socioeconomic readymade, a singular and perfect example of globalized techno-labor of the post-Fordist future. But how different is Taobao’s family-entrepreneurial micro-economies from those of, say, Etsy? Mother Holding Taobao Child fails to sufficiently do justice to the subjectivities that it aims to depict, leaving the viewer stuck in a gaze of exotic illegibility. Concerned as the duo is with the politics of cultural representation, this, of course, may be exactly the point.