In a time when environmental installation has lost its sense of genre-specificity, eclipsed by the holistic scope entailed by almost every artistic experience, Lucio Fontana’s exhibition “Environments” at Milan’s Hangar Bicocca underscores the primitive goal of such investigations: to augment the beholder’s temporal and spatial experience by undermining the static nature of perception as presupposed by traditional art forms. The exhibition includes nine Ambienti spaziali [spatial environments] and two environmental installations, all realized between 1949 and 1968 (the year of the artist’s death), most of which have been reconstructed for the first time through in-depth research in the respective archives of the artist, the architects who were responsible for engineering the works, and the institutions that commissioned them.

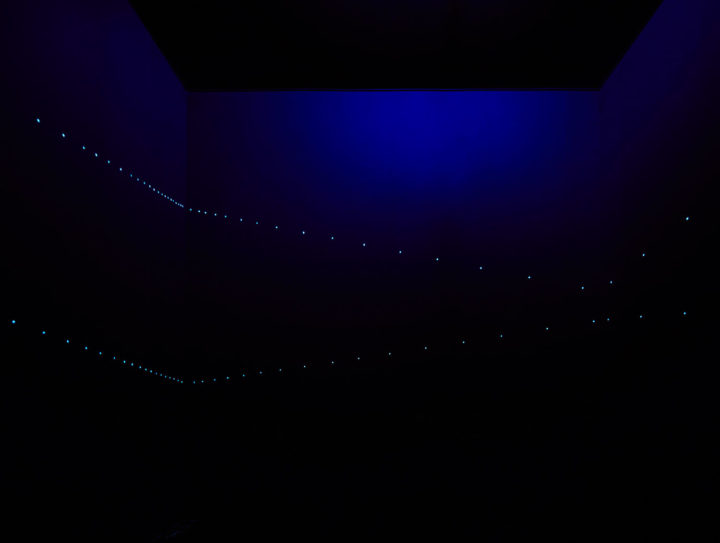

The 1949 Ambiente spaziale a luce nera [black light spatial environment], first presented at the Galleria del Naviglio, in Milan, sees biomorphic shapes made of papier-mâché and painted in florescent colors, suspended from the ceiling and lighted by ultraviolet lamps — a nod to aerospace discoveries of the time — while the 1968 Ambiente spaziale for Documenta 4, in Kassel, embeds one of the artist’s eponymous “cuts” within a maze-like all-white space. Facing the cut’s deep blackness, the visitor might wonder if she hasn’t actually stepped into the territory that lies beyond the cut: not just an extraterrestrial space, but the center of a black hole, the very embodiment of emptiness.

“Environments” arrives in the wake of a revaluation of the legacy of movements such as Fontana’s own Spazialismo and the contiguous Arte Programmata (the Italian version of kinetic art). Indeed, the exhibition forces a reconsideration of the purely technological content of early Italian environment art (ultimately, the role of the protagonist was here played by lighting) that the “ecological” claims of Arte Povera had supplanted. Such an inference could help frame the search for abstract but functional domestic environments that Italian Radical designers would pursue in the late 1960s and early 1970s — thus bringing together two rarely correlated major expressions of Postwar Italian creative production.