Mai-Thu Perret’s interest in combining utopian and political questions with sculptural and painterly practice remains at the center of her work. Yet, as seen in her most recent solo show at the Nasher Sculpture Center, there is now a slightly more pragmatic twist to her approach.

The installation “Sightings: Mai-Thu Perret” is at first hidden behind a glass wall covered with petroleum jelly, thus creating a blurred image (Untitled, 2016). Inside the gallery, the show reveals a complex composition mostly made of eight life-size mannequins (Les guérrillières, 2016). These sculptures offer insight into the life of a group of female warriors from a real Kurdish community located in the Syrian region, called YPJ or Women’s Protection Unit. The bodies and the garments of the warriors are rendered in a variety of media the artist has used in the past — glazed ceramic, papier-mâché, latex. Some have recognizable faces while others remain anonymous if not abstract. Besides the bodies of the guérrillières there is little else; there is no clear utilitarian objective, yet one has the uncanny sense that these warriors are real. A sculpture of a dog without eyes (Les guérillères VI, 2016) is placed next to a seated figure, suggesting the presence of emotional bonds within the community.

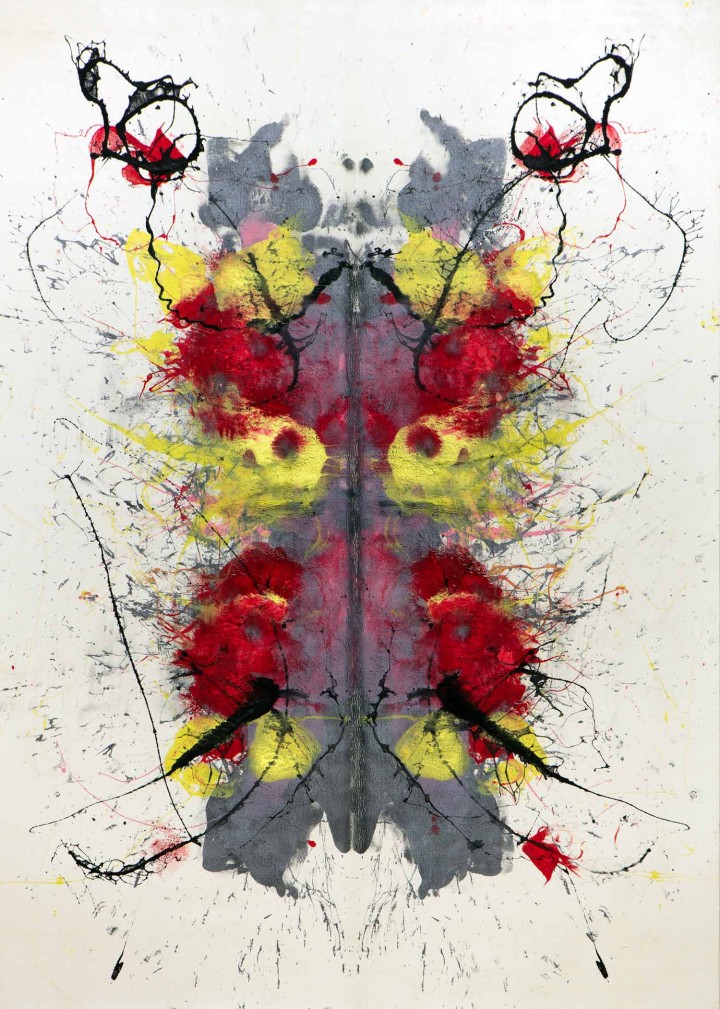

The installation also features a few symbolic sculptures: two gigantic eyes placed on the floor (Orchids grow in the hidden quarters of the palace. Though never displayed, they never cease emitting their fragrance, 2015 and This secret — so rarely met even in ten thousand ages — I will not tell, I will not tell, 2015) and a Rorschach-like painted synthetic carpet hung on the main wall (Agoraphobia I, 2016 — from a series Perret has pursued for many years now). These elements might symbolize a psychoanalytical dimension, a key to understanding the surrounding tableaux vivants, but their function is not fully clear, making their presence less necessary.

Since the beginning of her career, the artist has been guided by a modernist sensibility and a comprehensive knowledge of utopian historical movements — an approach best embodied by the notorious project The Crystal Frontier (1999). The presence and representation of the physical body is consistent in her work, also confirmed by an ongoing parallel practice in performance. At one time perhaps a site of concealed desire, her bodies have now found a new purpose and relevance. Following Pasolini’s admonition to “Throw the body into battle,” Perret’s figures have become fighters whose intentions are clear: mere survival is not enough; active engagement is necessary.