Originally published in Flash Art International no. 271 March – April 2010.

I keep telling myself, in fact, that the entirety of the exhibition can be thought of as a sign that refers to a missing signified. –Jean Francois Lyotard1

If the first decade of the second millennium will be remembered for the rise of the art fair, the decade before should definitely be remembered as the decade of biennials and, implicitly, the decade of curating. What we could call the era of curators demands that we redefine the practice of curating as an art in its own right, with its own structure and language. Among the many changes brought up by this relatively young science is the passage from a historical, ‘temporal’ perception to a ‘spatial’ understanding of art. For this reason, art historians are the least reliable candidates to lead the practice of curating. Their education, their forma mentis, is rooted in time and not in space. Given this assumption, we understand why some successful curators came from other disciplines. Jens Hoffmann studied stage directing, dramaturgy and cultural sociology; Francesco Bonami studied set design for theater.

In 2002, inspired by a conversation with Carsten Höller right after the opening of Documenta 11, Hoffmann initiated The Next Documenta Should be Curated by an Artist. He stated:

“Today it is nothing exceptional that curators occupy a more noticeable role in the process of producing an exhibition than some decades ago. While their task was historically related to the conservation of art works and the maintenance of a museum collection, curators began more and more to be creatively and conceptually involved in the making of exhibitions. […] The creative and intellectual exchange between artists and curators has […] been irreversibly changed and created a new condition in this relationship.”2

To echo these words are Marc-Olivier Wahler’s statement, “The best shows I have seen so far were always curated by artists,”3 and curator Lynne Cooke’s words:

“Among the most fruitful alternative strategies to have emerged […] have been certain ventures based on a notion of partnership, a shared endeavor uniting artist and curator in relation to a third element, namely one or more preexisting works. The seeds of this type of alliance lie in an exhibition model […] whereby an invitation was extended to an artist to present works from a museum’s collection in ways that would allow viewers to experience artifacts long familiar to them in new speculative relationships.”4

Curators are acting like artists and shows are functioning like complex works of art wherein the ‘original’ artwork is being “re-signified.” To present a constellation of exhibitions organized by artists is therefore meant as a contribution to curating as a further element of contemporary, multifaceted art practices.5

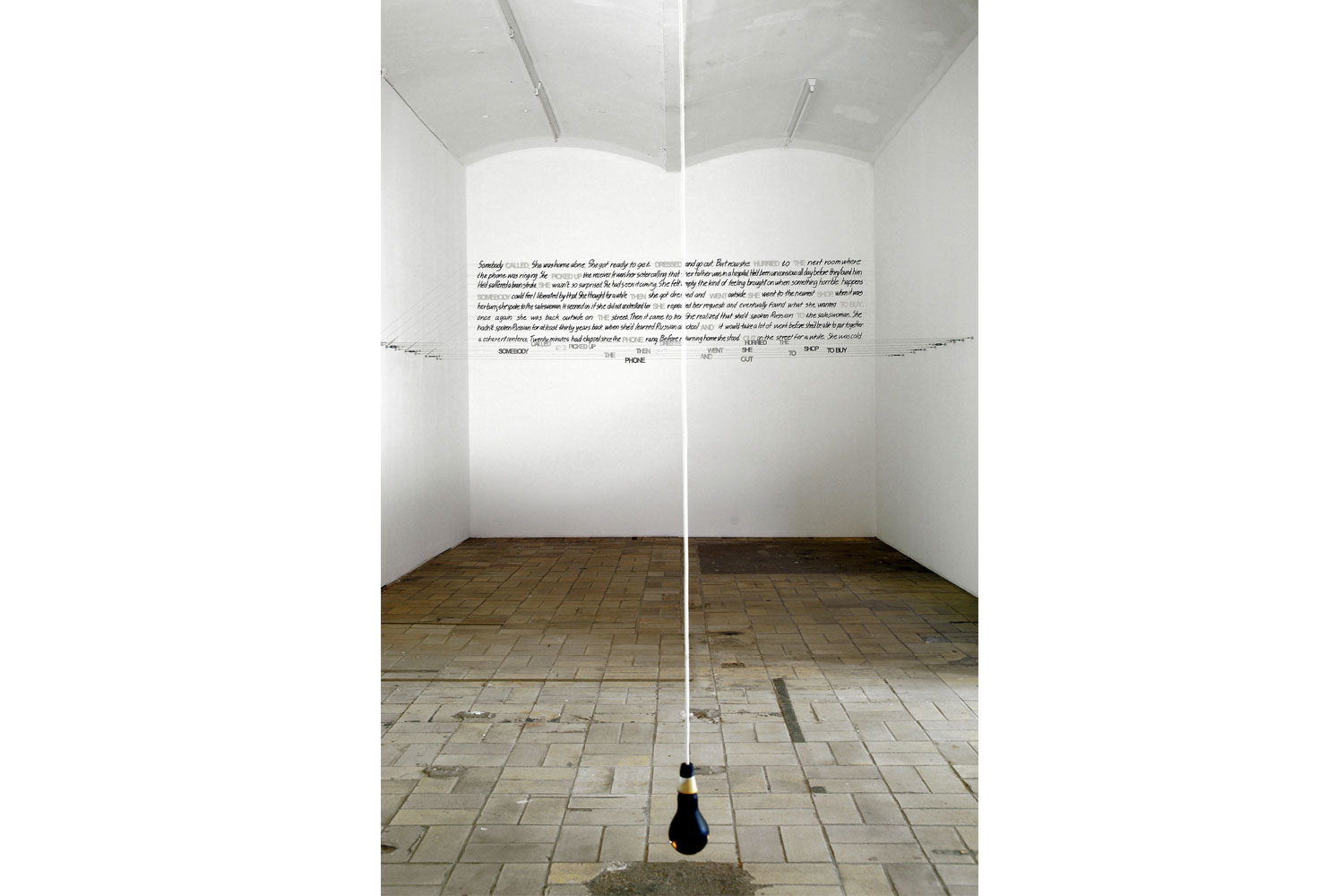

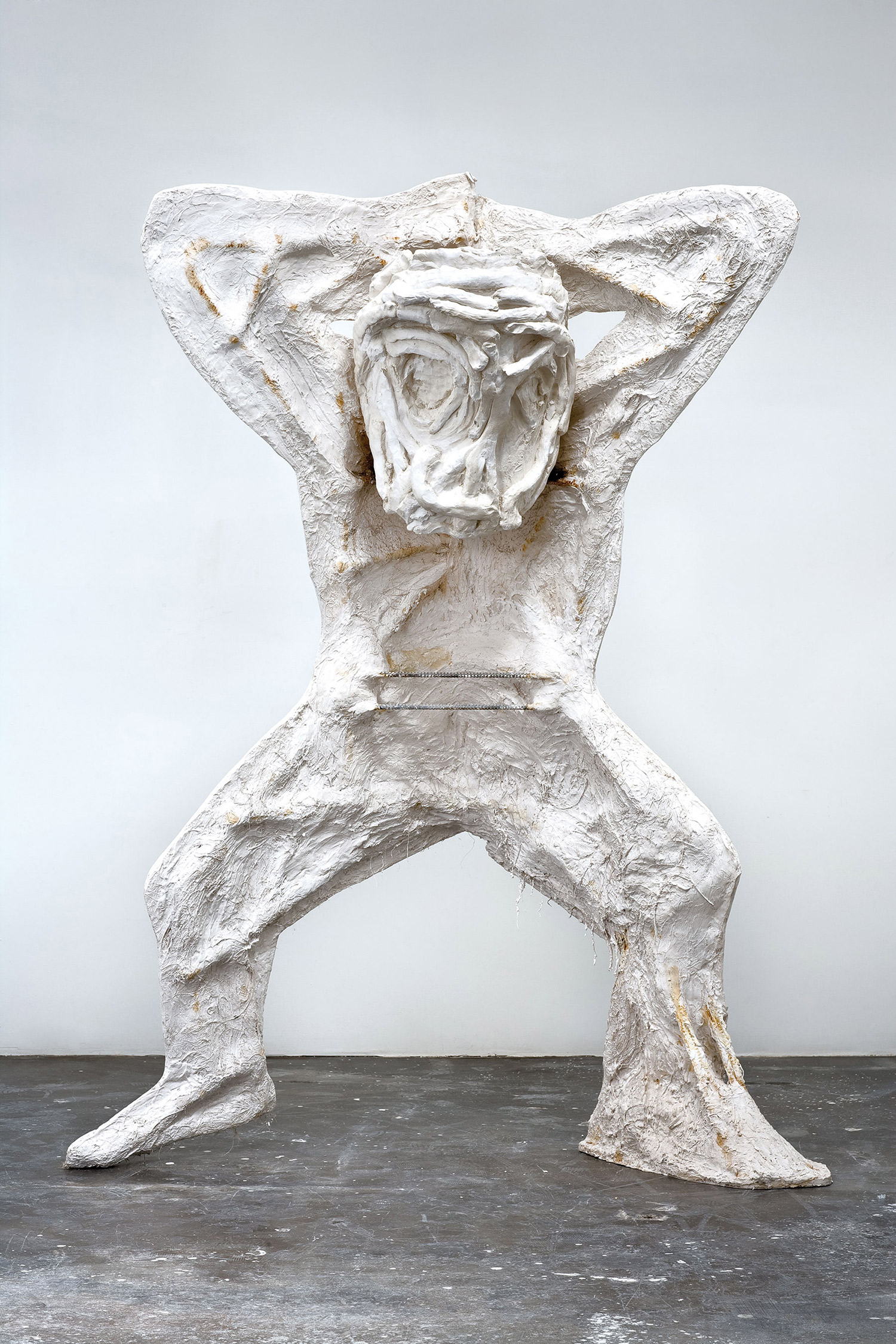

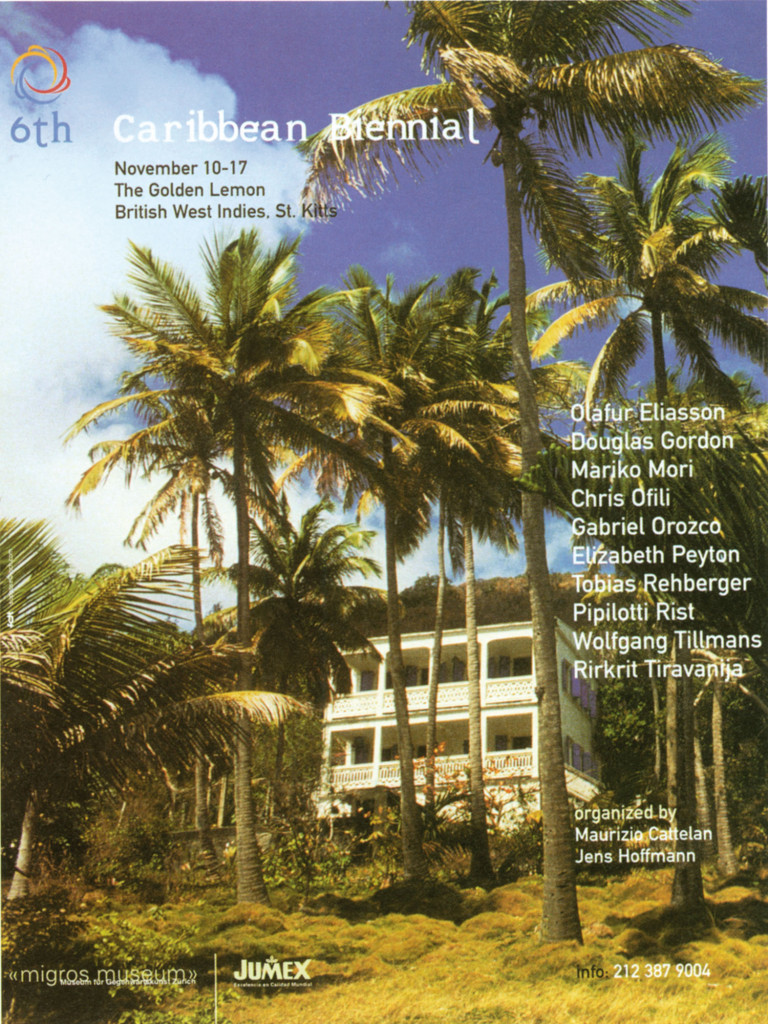

For instance, exhibitions are often considered as an extension of the artist’s practice. When Richard Hamilton, in 1966, organized The Almost Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp at the Tate Gallery — the first major retrospective by the artist in Europe, featuring something like 242 works — the artist included his own replica of Duchamp’s seminal piece The Large Glass. Here Hamilton made an extreme act; he subverted a format — the retrospective — supposed to be rigid by definition, testifying that its format is anything but a ‘sterile’ celebration. Much later, in 2000, Maurizio Cattelan started his personal campaign to promote biennials. After organizing the sixth Caribbean Biennial with Hoffmann, a veritable summer vacation, Cattelan confronted the task at hand when in 2006 he co-curated Of Mice and Men: the 4th Berlin Biennale. When questioned, Cattelan’s words seem to describe one of his own shows: “At the beginning we made these lists of possible biennials — a biennial without art, a biennial with only objects that were not art, and so on. […] For me it’s a show about men behaving like animals, and animals looking scary like and scared like humans.”6 This last sentence could even be used to describe Cattelan’s masterpiece, Bidibidobidiboo (1996), showing a squirrel shooting himself in its sad little kitchen that was designed to look like Cattelan’s family kitchen.

If these are perhaps the more subtle examples, the list is long enough to include The Uncanny, curated by Mike Kelley at Gemeentemuseum Arnhem in 1993; Moment Ginza7organized by Dominique Gonzalez-Fœrster8 at Le Magasin in Grenoble and Färgfabriken in Stockholm (1997); the historical Emory Douglas: Black Panther, curated by Sam Durant at The New Museum in New York (2009);the wonderful Scorpio’s Garden organized by Kirstine Roepstorff at Temporäre Kunsthalle in Berlin in 2009; and Strange Events Permit Themselves the Luxury of Occurring, selected by British artist Steven Claydon for the Camden Arts Center in 2007. The show included Carol Bove and Thomas Houseago, whose practices have much in common with Claydon’s, along with works by more ‘referential’ artists such as Eduardo Paolozzi and Richard Hawkins. Following the tradition is Pigment Piano Marble, which was organized by Mandla Reuter at Maipú 327 in Buenos Aires in 2006. The title refers to Marcel Duchamp’s essay “The Creative Act” which, as Amanda Coulson points out, “posits the importance of the audience in the creation of an artwork. The nod to Duchamp’s text, however […] also alludes to the Dadaist’s own trip to Buenos Aires […] to curate a Cubism show.”9

In some other cases, artists have become one-time curators in order to present their own peers. “‘Freeze’ occupies a mythical place in the written and verbal history of recent British art […] The show is regarded as a clinching moment when [Damien] Hirst gathered together this remarkable group of second and third-year students and recent graduates to denounce a new direction.”10 The show, where YBAs such as Sarah Lucas, Gary Hume and Angela Bulloch showed for the first time in 1988, could also be seen as an important way to understand Hirst’s practice, in which the actual objects are just a tiny slice of an enterprise that included the restaurant Pharmacy, the company Science Ltd, his activity as a collector (recently presented at the Serpentine Gallery), his merchandising firm Other Criteria, and his self-generated auction at Sotheby’s entitled Beautiful Inside My Head Forever.11 Similarly, Takashi Murakami in 2001 organized the exhibition-manifesto Superflat12 at MOCA in L.A., presenting the work of young Japanese artists like Chiho Aoshima, Mr. and Yoshitomo Nara. Drawn from common references to Manga culture, the show anticipated the meteoric expansion of Murakami’s production, from his marketing marriage with Louis Vuitton to his ‘bottega’ Kaikai Kiki (formerly known as the Hiropon Factory) and art fair Geisai. Speaking of the Far East, it is impossible not to mention Fan Mingzhen and Fan Mingzhu, organized in 2002 by Yang Zhenzhong, Xu Zhen and Tang Maohong in cooperation with Biz-Art, also including compatriots Yang Fudong, Shi Qing, Wang Wei, Xu Tan, Zheng Guogu, Lu Chunsheng, Kan Xuan, Liu Wei, Zhu Yu and Liang Yue. Almost resembling a collective installation, “the space was organized as a mirrored gallery. Spectators could choose between one of the two exhibition halls, going from one hall to another, only to discover that the exhibited artworks were all the same, except for small differences.”13

Another artist whose main practice has always been juxtaposed by myriads of b-side projects is Steven Parrino. For Parrino, curating The Bastard Kids of Drella Part 9 in 1999 at Le Consortium in Dijon and The Return of the Creature, in 2003, at Künstlerhaus Palais Thurn und Taxis in Bregenz represented an opportunity to support younger artists whose work he admired. Incorporating posters, zines and noise music into a sort of “low-budget Gesamtkunstwerk,” Parrino supported young artists like Amy Granat, Mai-Thu Perret, Banks Violette, Gardar Eide Einarsson and Richard Aldrich. Exhibiting the same mood with an undeniable dose of irony was Fia Backström’s lesser new york, the “half-show/half-installation”14 she organized in her apartment in 2005. “Mounted by the artist as a complementary section to P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center’s ‘Greater New York’ […] lesser new york replaced the more market-friendly ‘piece-by-piece’ presentation with Backström’s hanging strategy,” which she describes as “an approach between communist wallpaper and shopping layout.”15

In New York, artist-curated shows are a true trend, with examples like The first two friends and so on, curated by Rob Pruitt and Jonathan Horowitz at Andrew Kreps; Who Is the Protagonist? curated by Ohad Meromi at Guild & Greyshkul; Beneath the Underdog, curated by Nate Lowman and Adam McEwen at Gagosian; A Twilight Art, by Lisa Oppenheim and Jessie Washburne-Harris; and the massive Who’s Afraid of Jasper Johns curated by Urs Fischer and Gavin Brown.16

Sometimes artist-curated exhibitions become the starting point for museum shows. If the aforementioned shows curated by Parrino inspired part of his Palais de Tokyo retrospective, Science Fiction, curated by Peter Halley in 1983 at John Weber — presenting the ‘unknown’ Prince and Koons alongside Judd and Smithson — should be mentioned as well. Indeed, Science Fiction was recreated at Le Consortium as part of the larger group exhibition entitled “Une autre affaire.”17

The Tirana Biennale 1, directed by Flash Art’s founding editor Giancarlo Politi in 2001, also belongs in this constellation. Conceived as a plethora of shows-within-the-show, the Biennial had 38 curators, including artists Vanessa Beecroft and Maurizio Cattelan, who also exhibited in “Sharing a Sponsor,” curated by Flash Art’s editor, Helena Kontova.18 The magazine’s former U.S. editor, Francesco Bonami, was also a curator in Tirana as well as at Aperto ’93, another Flash Art project. Appointed director of the 2003 Venice Biennale, Bonami described his Biennial as an “archipelago” (here too the spatial metaphor!) and curated it according to a peculiar methodology, which was similar to that used in Tirana and at Aperto ’93. Bonami invited a series of co-curators with whom he “shared” his role, among them artist Rirkrit Tiravanija, co-initiator of “Utopia Station” — a traveling cultural platform started with curator Hans Ulrich Obrist and art historian Molly Nesbit — and Gabriel Orozco, who curated in Venice The Everyday Altered, a project that ideally continued Lines of Loss, a group show of Mexican artists he organized at Artists Space in New York.

To ‘amplify’ his choice, Bonami invited Tiravanija and Orozco both as curators and artists in the section he co-curated with Daniel Birnbaum, called Delays and Revolutions. When talking about Venice, it is widely acknowledged that the most relevant, successful and groundbreaking show of the last edition in 2009 was The Collectors, a sprawling exhibition curated by Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset, which occupied both the Nordic and the Danish Pavilions. A mixture of fiction and reality, the show included works by artists like Maurizio Cattelan, Sturtevant, Klara Lidén, Simon Fujiwara and Wolfgang Tillmans, together with Fredrik Sjöberg’s Fly Collection, the porcelain collection of their dealer Massimo De Carlo and some hardcore illustrations from gallerists Daniel Buchholz and Christopher Müller. And this is not new for Venice. In 2007, every connoisseur acknowledged the fact that The Hamsterwheel, organized separately from the grand show by Franz West, was the most relevant project of the entire biennial. Characterized by a sprawling display, the show brought together more than 30 artists (Urs Fischer, Rachel Harrison, Georg Herold, Gelitin, Paola Pivi and Erik van Lieshout were among the most memorable) whose works were connected in “cryptic ways.” The invited artist Jean-Marc Bustamante stated:

“As a title The Hamsterwheel is really about play. It pokes fun not only at the art scene, but also at the artists themselves. We’re all scurrying around at breakneck speed and getting nowhere at the same time […] a giant new game was set in motion each time, without curator’s directives, just from of our own auto stimulation.”19

Although the next Documenta will probably “not” be curated by an artist, Venice is definitely leading us in a promising direction.