Joel Kyack: The red light is on.

Laura Owens: Do you think we can just ask each other questions?

JK: Sure.

LO: Do you like to look at art?

JK: Yes.

LO: Some artists don’t like to look at art.

JK: I don’t find a whole lot that really turns me on but I like seeking it out. Even the stuff I’m not digging is somehow formulating an argument in my own work. Or sometimes when I see something I’m really puzzled by it excites me and shakes me into action.

LO: Has that ever happened to you with a painting?

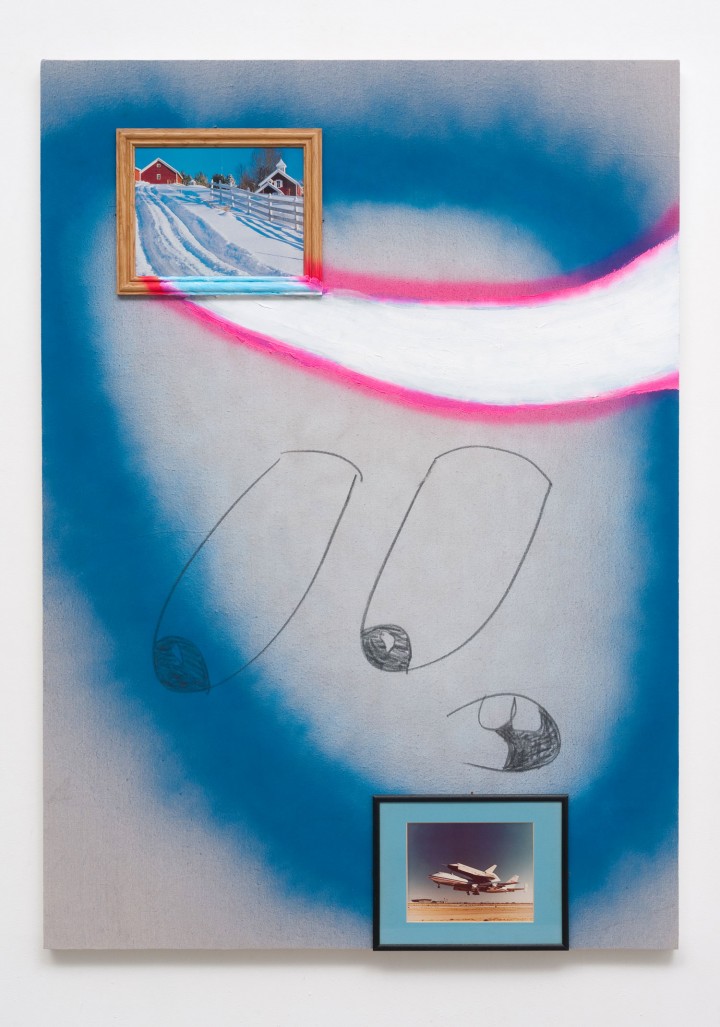

JK: Just recently actually, with your show “12 Paintings” at 356 S. Mission Rd. and Llyn Foulkes’s show at the Hammer Museum. There was this one piece in Foulkes’s show in particular called Flanders (1961–62), where he’d taken a framed painting and just put it in the larger painting. So this reference that he was making to something that he had seen in the world wasn’t really a reference, it was just the actual thing stuck into the painting. And because the framed painting felt so finished on its own, simply by being in a frame, there became this silent conversation between the piece it was and the piece it had now become. All the information I needed was right there.

LO: I also really liked the Llyn Foulkes show, but was looking more at his use of trompe l’oeil. How it creates these telescoping versions of reality. There’s a painted reality, and then there’s a painting within that and a painting within that. His use of shadow and three-dimensional collage: “Oh, that’s a table…” “No, that really is a table because it’s sticking off the painting.” In your new work, you’re putting these found framed paintings, posters, photographs on the actual painting. It highlights an awareness of the fact that you’re constructing this thing. It makes the body of the viewer active. They have to engage with it, and it’s a kind of awakening to the process of thought involved in its making. As opposed to a painting that’s transporting you to another world, where the body in the gallery or even the physical space in front of the art is much less important.

JK: Maybe this awareness you’re describing serves to get around the linear experience of being transported to another world. Maybe by compounding levels of awareness you allow the work to be this singular, non-linear thing.

LO: I think what you’re bringing up with Llyn Foulkes — which happens in a lot of really good art — is that the collage has this element of demonstrating the process, and that is just laid bare. It’s like saying: “It’s permissible to see how I made this thing. I cut this out of here and I glued it on.”

JK: This revealing of process, or having it be very direct and unrefined, seems radical to me given that the things we generally interact with in our daily lives are so insanely refined. Like a cell phone — every rough edge is gone. It is a thing that is solely about its end use. And when these types of objects fail, even slightly, there’s nothing that looks worse. Forget function — it has failed its intention. Its like Donald Judd’s early sculptures at Marfa, they look like shit because, if just the corner is a tiny bit off, I’m like: “The whole thing’s bullshit now.” I’d argue that the tiny flaw — which is inherent over time — ruins it because its intention is exactitude. Even getting into a new car feels like a human never even touched it, like some giant robot pooped out this other robot.

LO: Do you think that means that art has to allow its flaws or have its own self-evidence built into it in order for it to be authentic?

JK: I think there’s other ways of doing it, and I think that depends on how savvy you are. You did it in your last show. I went back to see it several times because I think I was just pissed about why I liked it so much. It was like when I first started playing in bands… We would go to some show and be so excited by the band that we would go and immediately practice at like 1:30 in the morning. What I liked was that it just felt so confident and just all the way, no apologies, all guts.

LO: It’s funny because our artist colleague Michael Decker said to me about that show: “Your art comes across like you were the kid who someone on the playground picked on a couple times and you took it. And then you went home and you came back with some kind of machine that just laid everyone flat.” I think he was trying to say it looked like I had something to prove and I over-proved it. But when I was making it I was thinking more like, I’m fucking sick of seeing all this work that is aestheticizing the idea of not trying, this aesthetic encapsulation of something that says, “I didn’t try and that’s really cool.” I just came to the conclusion that it was really embarrassing to try, and I was like, “Oh, now I’m going to try really hard to do it.”

JK: Those paintings have these giant exaggerated gestural marks that seem to have come from smaller gestures, and in that translation of scale and intention — from the actual gesture to the interpretation and remaking of that gesture — you don’t leave anything out. The mark is itself, its interpretation, and its representation as a mark — all three.

LO: I didn’t realize until afterwards that this idea of the frame within a frame or the painting within the painting was happening. Those big marks — when I started talking about the work I was like, “Oh my God, that big mark is made out of all these other big marks.”

JK: It begins compounding.

LO: Like a Russian nesting doll.

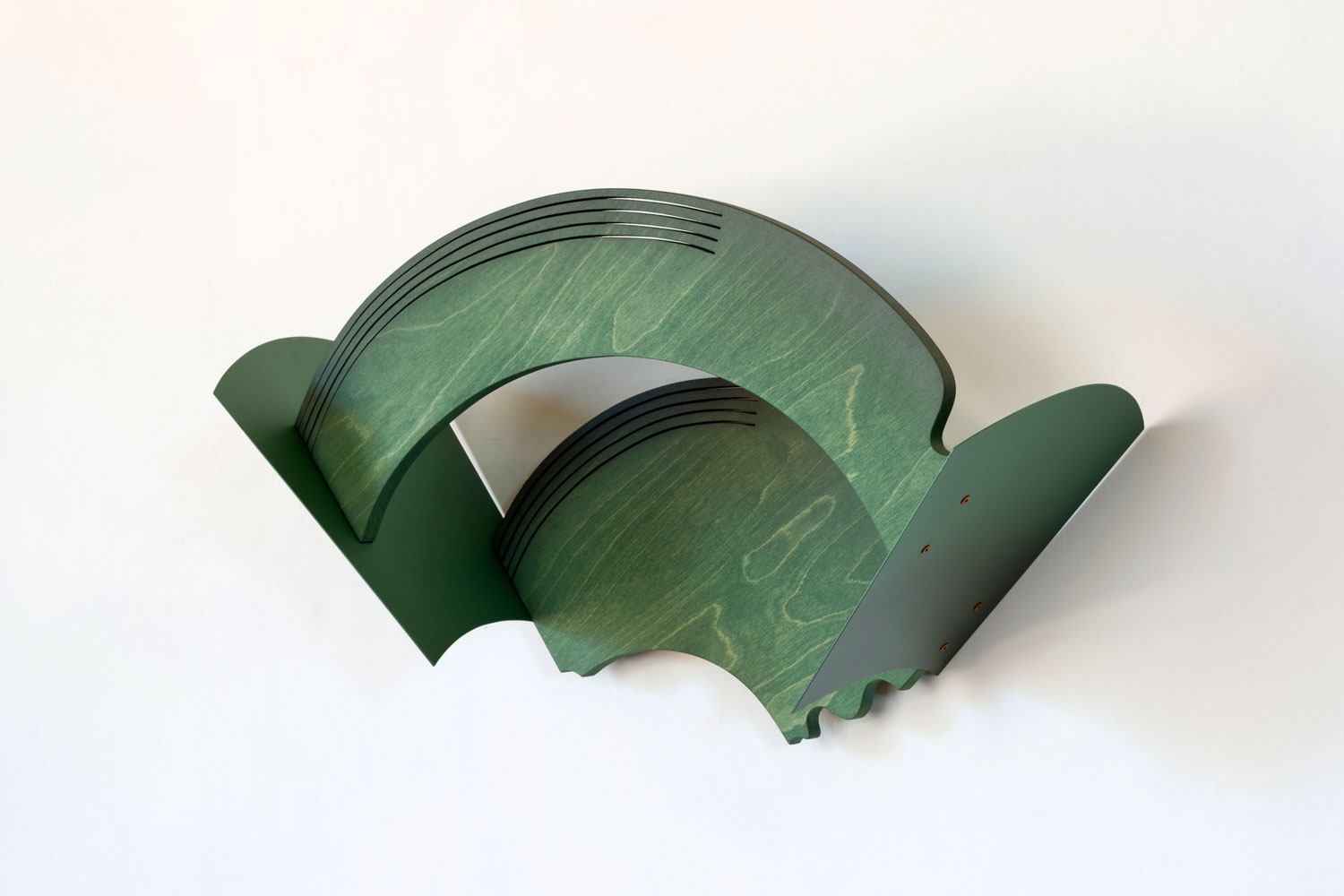

JK: I thought of “12 Paintings”as being really generous. That’s something that I think is perceived as not cool right now in contemporary art. It’s not cool to be generous to your audience. Shit, your show and Foulkes’s felt generous enough that I started thinking that I could make a painting, that I could translate the energy that is, to me, inherent in drawing.

LO: When I walked in your studio that was exactly what I saw. I was like, “This is an amazing drawing.” Because with simple gestures you had really just drawn on the canvas and it felt like a very complete thing with a few marks.

JK: I had always felt very confident about sculpture or performance or music, but painting felt scary. Maybe about the third time I saw your show I went to the studio and stretched the first canvas. I was just like, “I’m going to do this fucking thing right now.”

LO: How do you go from not stretching a canvas to stretching a canvas?

JK: Shit, I don’t know. I think you go from desire to action when you have no other option. And the second I did it I was like, “This makes sense, so now I’ve got to go and do this as well.”

LO: I wonder if the argument against painting could be because it has this historical primacy at its center. It’s just this thing that gets rebelled against, you know? Maybe it has something to do with it being read as art.

JK: Very simply read as art?

LO: If you ask an average person “What’s art?” they say, “Paintings.” Somehow your brain fully believes in that. With sculpture, you have these materials to deal with. Even a Donald Judd is referring to…

JK: …other things made of steel.

LO: Things that are made for the world have a function and are awesome.

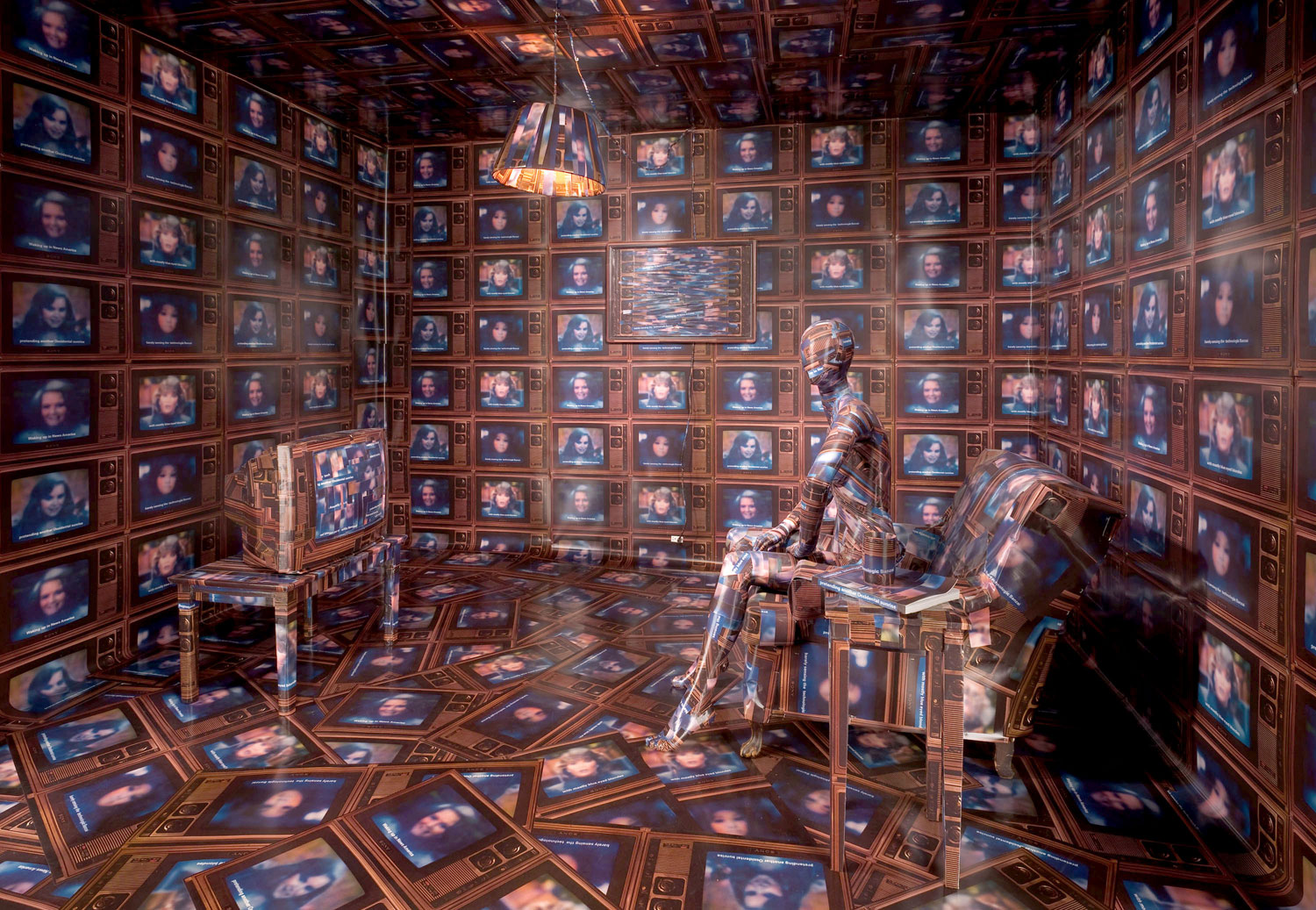

JK: It’s interesting — this referential dialogue with the “real world” that a piece is in conversation with… I’m reading Artificial Hells by Claire Bishop right now, and she talks about this interesting point where when an artist does something — let’s say you build a community center in the gallery… Her point was that criticism of those sorts of works is almost exclusively reserved for comparison only to other works of art. It doesn’t get compared to or measured against the actual thing in the world that it’s performing as.

LO: Like an actual community center.

JK: Exactly. The merits of the project can — and I’d argue should also — be talked about in relationship to the actual “real world” thing it’s in conversation with: the community center, functional steel structures, the café. We can just talk about it as a café. Is it a good café or a bad café, compared to other cafés? Since art has gone so far as to include almost any situation, I think it’s exciting that all processes are game to any single artist. I think in that idea there’s this sense of freedom, and that sense of freedom is a valuable thing to exercise and convey.

LO: I think making paintings it’s weirder though than when you have the kind of fluidity of making art out of many different materials. You’re literally using your hand and the paintbrush, and when you feel yourself making the same marks over and over again there’s a consciousness to it that is always too self-conscious. And it’s what can easily end up feeling stayed and overworked.

JK: I’m always a little wary of respect in general, and when that sort of self-indulgence happens, it seems like this awkward, weird respect for one’s self, for ones own work. It’s like exalting what you do and then behaving respectfully towards it. It becomes a trap.

LO: That’s really subtle. That’s a quality of dialogue with yourself, knowing you’re imitating yourself from a year ago. Or maybe there would be a great sense of freedom in doing the exact same thing every day.

JK: Hard to say.