The years was 1982, seven years before the fall of the Berlin Wall. Christos M. Joachimides, a Greek art historian, and Norman Rosenthal, from London’s Royal Academy, organized what was arguably one of the most historically significant global painting surveys of the 20th century. “Zeitgeist” was the term chosen to define the title of this momentous exhibition. Held in the center of Berlin at the Martin-Gropius-Bau, a former arts and crafts museum of the Prussian State, “Zeitgeist” brought together 45 of the worlds’ most driven and symbolically heroic artists of the moment. Using Joseph Beuys as a springboard and catalyst for an ever-widening perspective of personal liberation and mythos within the spirit of the times, painting was brought once again into the global forefront of intellectual, spiritual, cultural, political, and ethical concerns. Truly, the only analogy that I can conceive of with regards to the cohabitation of these 237 paintings (with few sculptures) is ‘possibly’ the giant tigers of the Roman Coliseum padding their throbbing claws on the hot pit of the dry ground as they roamed with assured sight and strength.

Combining the best of the American and German Neo-Expressionist painters, along with the Italian Transavantgarde painters, “Zeitgeist” gave the world the opportunity to witness an artistic tsunami of painterly possibility. As it should have, it raised a political and philosophical debate of unprecedented scale within the artistic intelligentsia of the moment. Of the 45 artists, only one was female — Susan Rothenberg, who’s austere and rhythmic linear depictions of horses held up to any and all competitors in terms of surface and mark-making. So much of the critical focus was devoted to postmodern jargon, with ideas of over-intellectualized rhetoric, that the greatest lesson of “Zeitgeist” seemed to be overlooked: that here was a perfect storm of revived interest in painting, all at the same time and on a global scale. This “return to painting” was, and is, something that happens continuously in the development of art. However in 1982 it was happening with a force of inquiry that hadn’t been seen since the Renaissance.

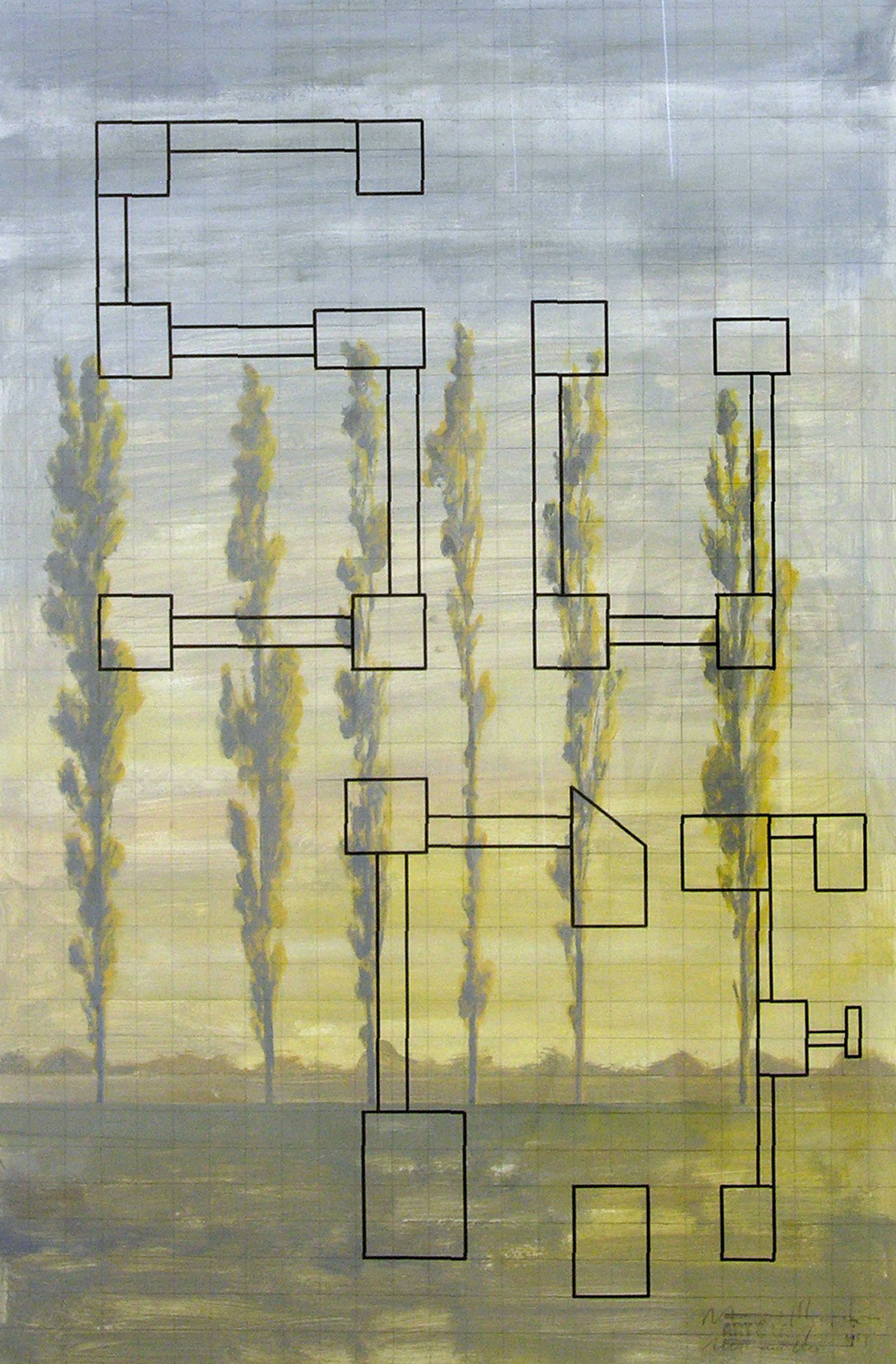

For the German painters in “Zeitgeist,” including Polke, Baselitz, Lüpertz, Hacker, Fetting, Middendorf, Dahn, Kiefer, Immendorff, Tannert, Salomé, Bömmels, Dokoupil, Hödicke, Koberling, Büttner, Höckelmann and Penck, it was a grand occasion to showcase the new ‘authentic’ German paintings of the moment. Many of these painters continue to create exceptional and historic works in the vein of their predecessors such as Nolde, Mueller, Kirchner, Schmidt-Rottluff, Pechstein, and Hecknel. Just as with this earlier group of German painters, the “Zeitgeist” group saw their paintings as a bridge between the ancient past and the near future. Over time, Polke, Baselitz and Lüpertz remained as outspoken voices of the “Zeitgeist” generation, and their works found root in this imperative exhibition where their bold colors and expressive mark-making could be better understood in relation to other ‘flashy’ works of then-young Americans. Such relationships with the German Capital Realists and their more cerebral approach to the picture-plane were heretofore muted. Other regional painters, including those from Austria, and Per Kirkeby from Denmark, along with a few artists from UK including the team of Gilbert & George (an exceptional inclusion in relation to the power of image and the new international picture), gave “Zeitgeist” further reach and breadth. But, the central jockeying for position was still very much between the Germans, Americans and Italians. “Zeitgeist” was an exhibition marked by contradiction — not an exhibition where you expected to see all of the works forming a coherent dialogue. This quality resounded throughout the upper and lower halls of the Martin-Gropius-Bau. When one saw an Italian painter such as Mimmo Paladino head to head with an American painter like David Salle, a discord resulted. Not a discord in terms of ‘what’ was the subject’s iconography — because both if not all of the painters in “Zeitgeist” were painting using the surrogate of the figure to relay their methodologies — but in terms of ‘how’ the subject was painted. This is a very important point because it brings up the fact that, again, many of these painters of the “Zeitgeist” generation were actually real ‘painters,’ and not political activists and the like disguised as ‘artists.’ One sterling example of this idea would be the inclusion of the American painter Andy Warhol. Warhol created massive paintings with depictions of the ‘Friedrich Monument’ in strong dramatic hues of orange and black. Ever the subversive, he threw Germanic aristocracy up against itself in the form of a picture, a painting, just as he did with the American audience and his early Campbell’s soup can paintings. He reflected the given culture upon itself, and when one could see that as the structural armature of the painting, then one could see the façade of it as well, thus leaving the viewer free to interpret the painting in terms of ‘Painting.’ How the thing is made, what is the mark doing, etc. This extends into the other participating Americans including Twombly, Morley, Schnabel, Rothenberg, Salle, the strange inclusion of Frank Stella and other Americans dealing in mixed-media works, i.e. Morris, Borofsky, and James Lee Byars. The Americans had the flattest feet and the biggest fists. Whereas the Germans had the weight of history backing them up, and the Italians the nuance of technique, the Americans were loud, flamboyant and brash, in a good way. The bombardment of the American paintings included in “Zeitgeist” gave an urgency to the mood of the exhibition. These were painters that were working without a net. They didn’t have the weight of history. If there appeared to be such then it was only through poetry and imagination that this was to be — case in point Cy Twombly. Twombly’s “Goethe in Italy” paintings could only be something imagined by the artist, an American, and yet one with a profound yearning and love for Italy and the works and stories found there.

The Italian painters that were included in “Zeitgeist,” the painters of the Transavantgarde, what the Italian art critic Achille Bonito Oliva defined as “beyond the avant-garde,” reintroduced ‘joy’ into “Zeitgeist.” Now, joy as it is defined here is a joy of immense weight and measure. It is a ‘poetic’ joy, an ‘Italian’ joy; this is virtually impossible for any painter outside of Italy to express. In fact it is one that can only be observed and described by a viewer outside of the immediate artistic inquiry. There is a ‘poetics’ to the work of the Italian painters who participated in the “Zeitgeist” exhibition. Paladino, Calzolari, Cucchi, Chia and Clemente, along with Merz and Kounellis, brought wild theatrics not only to the narratives of their paintings, but to their improvisational and masterful ways of paint application. Heavily influenced by dream, symbolism, and psychosexual phantasmagoria, the Italians offset the weighty unreality in their works with an almost unbearable lightness of touch, even when heavy impastos were being used in certain paintings. This is what gave their paintings the added girth needed to take on serious contention with the American and German painters of “Zeitgeist.”

We are now approaching the 30th anniversary of the exhibition. The Berlin wall has fallen. Change has come to that area of Berlin and its surroundings. Yet, there have also been very important painters and artists developing all over the world since that moment in 1982. No serious painter working today that came to fruition after “Zeitgeist” is unaware of the exhibition. That fact in and of itself is a massive triumph. The question remains: “What would the international landscape of painting look like today if there hadn’t been this brazen attempt, with an almost Herculean strength on the part of the curators to actually try and harness the energy, enthusiasm and revelry of the moment back in 1982?” Certainly throughout history great change occurs when one word rings true, and that word is ‘revolution.’ If there has been one exhibition in recent decades that has brought true revolution and change to the course of world painting, it has been the Zeitgeist International Art Exhibition held at the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin, 1982.