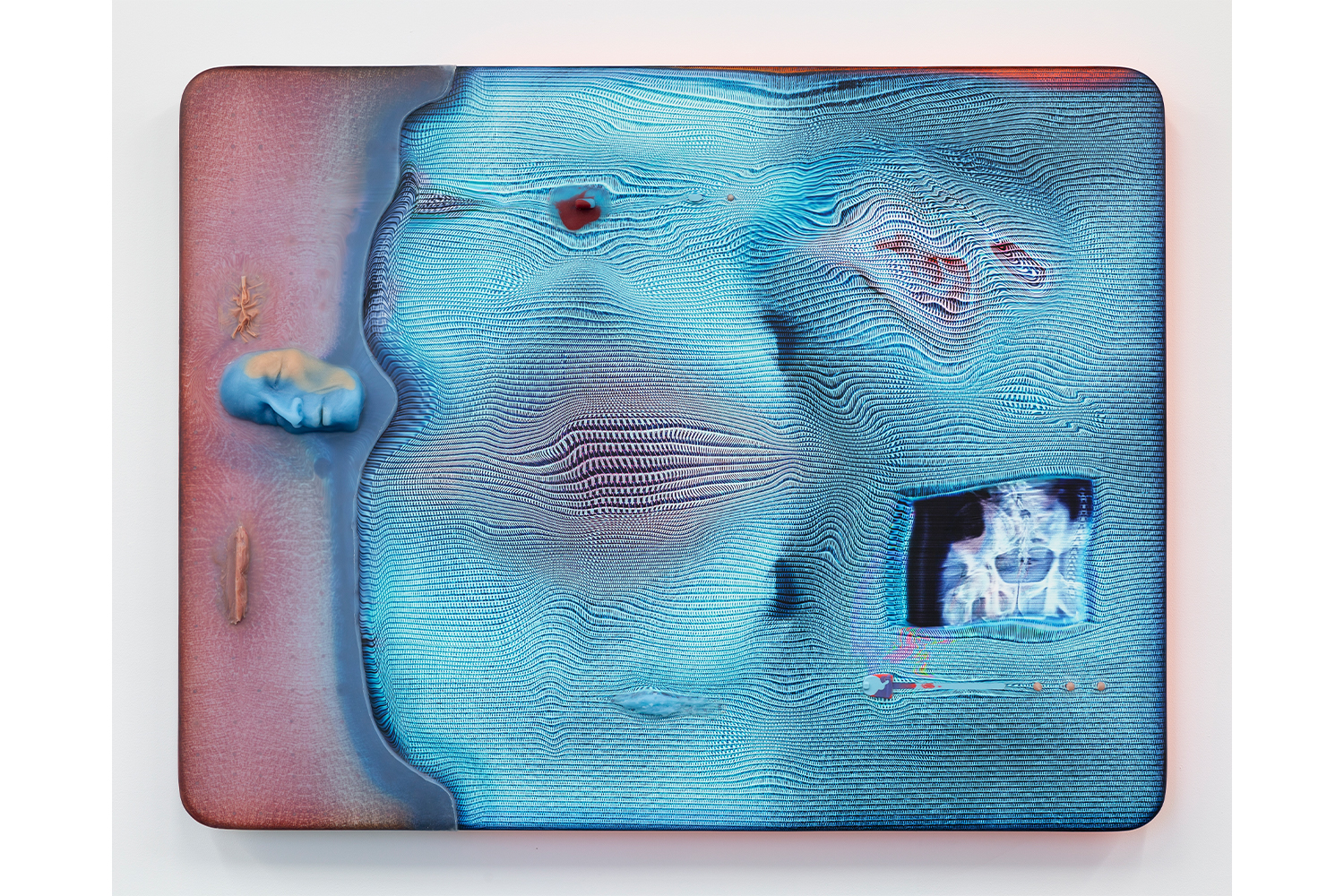

As of late, “prescient” has become the preferred modifier for artist, Tishan Hsu. Indeed, as framed by the recent retrospective that traveled from UCLA’s Hammer Museum to New York’s Sculpture Center, his output since the mid- 1980s has anticipated — and in many ways mapped with eerie accuracy — the convoluted interdependence between body and screen that now defines all aspects of our lived reality. His wall reliefs and sculptures are punctuated with fleshy openings and orifices — Cronenbergian mouth-eye hybrids adrift in ergonomically shaped vessels that seem to hover just off the wall (in reality recessed plywood panels with edges and backs painted in fluorescent tones to create the illusion of backlighting). This effect predates the touchscreen by decades, even as it aptly captures its distinctive feel. An often-cited work, Closed Circuit (1986), with its rounded corners and cyclops visage, even manages to conjure Instagram’s logo thirty years before the social network ever popped up in anyone’s app store.

Over the years, his technique has evolved hand-in-glove with new photographic, imaging, and digital technologies to create increasingly complex fields and effects that modulate with the flux of our media landscape. More recently, he’s utilized these networked coordinates to address questions of lineage, familial connections, and geographic displacement, utilizing the vicissitudes of affect to expand unitary conceptions of “identity” and its politics while simultaneously rewiring the expectations of technologically geared art. In doing so he has laid down a rich and varied artistic groundwork that reverberates across a young generation of artists that continue to mine the bio- tech convergence (figures as diverse as Josh Kline, Anika Yi, Julia Phillips, and Max Hooper Schneider come to mind). Indeed, the overall impression, looking back, is less that we are witnessing a practice evolving as we are our own cultural evolution finally catching up with it.

Painting as Screen

All of the above is perhaps even more remarkable for a practice that is arguably rooted in painting. Born in Boston to Shanghainese parents (displaced by the Cultural Revolution), Hsu embraced this most traditional of mediums from the onset, diving into classical techniques as early as elementary school and into his teens. Stints in wildly disparate places — from Switzerland to Wisconsin — are linked by this ongoing passion, and despite ultimately studying architecture and environmental design at MIT, his keen sense of form and color formed an unshakable foundation. Settling in New York in 1975, Hsu connected to Pat Hearn, the ex-punk-turned-emerging-gallerist who was to become one of the cornerstones of the then-burgeoning East Village scene. Her predilection for disruptive points of view challenging the codes of painting made for a natural fit, eventually yielding a series of seminal shows, beginning with his solo debut in 1985.

It is impossible to capture the strangeness of the early work, especially in its original context, but pieces like Portrait ( 1 ) (1982) or Plasma (1986), with their alien contours and bulbous protrusions, provide a good indication while attesting to Hsu’s expert manipulation of unorthodox yet humble materials. Their fleshy expanses — hovering between base materiality and slick illusionism — certainly made an impression, but lacking any immediate points of reference or critical coordinates they were also largely misread. At the time, Hsu was lumped into the rubric of neo-geo, a term that gained some traction in the late ’80s but is now mostly notable for its general vagueness — a portmanteau for a broad range of practices favoring a hard-edged approach that at times verged on (or deliberately embraced) kitsch. Fellow Hearn stablemates Philip Taaffe and Peter Schuyff were also shoved into this “next big thing,” which was sometimes referred to by the hipper postmodernist moniker “simulationism.”

If we’re speaking about formal affinities alone, perhaps Peter Halley’s early cell and conduit paintings might have been a more apt analogue. But the problem with any purely formalist reading was that it grasped only half of the equation, and in so doing missed the animating core of Hsu’s practice. For in trying to invent a new syntax of painting for himself, Hsu was also brushing up against the massive technological shifts reorganizing everyday life in the 1980s. Rather than an accelerated fetishism of consumer objects, his was a concerted effort to grapple with an emergent material reality that was remapping our own experience of the body. And this was not just a theoretical pursuit; for Hsu it was also lived practice, having worked a night job at a word processing terminal on Wall Street during grad school, perhaps one of the earliest jobs involving prolonged stints with a computer monitor. It was an experience that left an indelible impression, as he notes in a recent interview: “I felt that there was this screen world that was very different than television because I was interacting with it…I’m sitting in front of this screened object for many hours, several days a week, and my bodily, physical, material presence was very much there. I felt there was this paradox between the illusionary world of the screen and the physical reality of my body, and that I wanted my work to account for both. I felt that my body in front of that screen still really counted.”

Membrane to Membrane

It is this insistence on the body and nuanced understanding of its communion with nascent technologies that differentiated Hsu from his peers and also placed him decades ahead of contemporaneous theorizations of digitalization and its far reaching cultural impact. This was particularly the case as the 1980s transitioned into the 1990s, and strands of sci-fi, speculative fiction, and other paranoid, somewhat techno-phobic lines of thinking congealed into the slick, plugged-in aesthetic of cyberpunk. In stark contrast, Hsu committed to a far more sober approach: rather than the body’s absorption into or effacement by the technological, he traced a complex co-presence facilitated by the very materiality of his objects. He notes: “There were physical properties of the world I was experiencing having to do with my body and the screen, and whether I could integrate those visual and physical properties, that drove the early work. I did not want the sensibility I was trying to convey to be dependent on one medium. Working in different material formats (2-D and 3-D) required I have a clearer understanding of what the work was trying to do and/or reveal to me.”

This is the operating principle of a sculpture like Vertical Ooze (1986), a stack of three hospital-green tiers that evoke an architectural model, a fountain, or a trippy distortion of Anthony Caro’s Euclidian arrangements. The interiors of each segment are lined with tiles that are as banal as any found in a public bathroom, yet maybe also nod to the elasticity of the pixel (this is how I read the nub-like protrusion on the bottom tier). This hybrid object — brushing up against the virtual, but also reveling in its own gravity — posits an encounter between two distinct but interrelated corporealities: viewer and object. In so doing, it opens up a line of thinking that is less interested in projecting visions of an anxious future than mapping the vicissitudes of an ever-shifting present.

It is worth stressing the radicality of Hsu’s position at this specific historical juncture. Art historically, he adapts the concerns of Minimalism and its virtual forms to elucidate the experience of our networked era; he also anticipates many of the critical threads taken up by what was to be called “new media” art of the 1990s and early aughts without succumbing to the spectacle of gadgetry. More generally, he offers a counternarrative to the posthumanist view of technology that would entrench itself in our cultural consciousness (and arguably retains much of its thrall even today). Here, the computer screen (now the phone) was seen as a portal into a new disembodied reality. The is the vestigial body as dramatized vividly in a number of cinematic works from the period, including David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983), Ghost in the Shell (1995) (based on Masamune Shirow’s 1989 manga of the same name), and, of course, the Wachowskis’ The Matrix (1999). These drew heavily from or resonated with contemporaneous theoretical contributions, including Jean Baudrillard’s work on Simulacra and Simulation (1981) as well as Fredrick Jameson’s seminal 1991 tome on postmodernity. As critic N. Katherine Hales wrote in 2000, this tech worldview “presumes a conception of information as a (disembodied) entity that can flow between carbon-based organic components and silicon-based electronic components to make protein and silicon operate as a single system… In the posthuman, there are no essential differences or absolute demarcations between bodily existence and computer simulation, cybernetic mechanism and biological organism, robot teleology and human goals.”

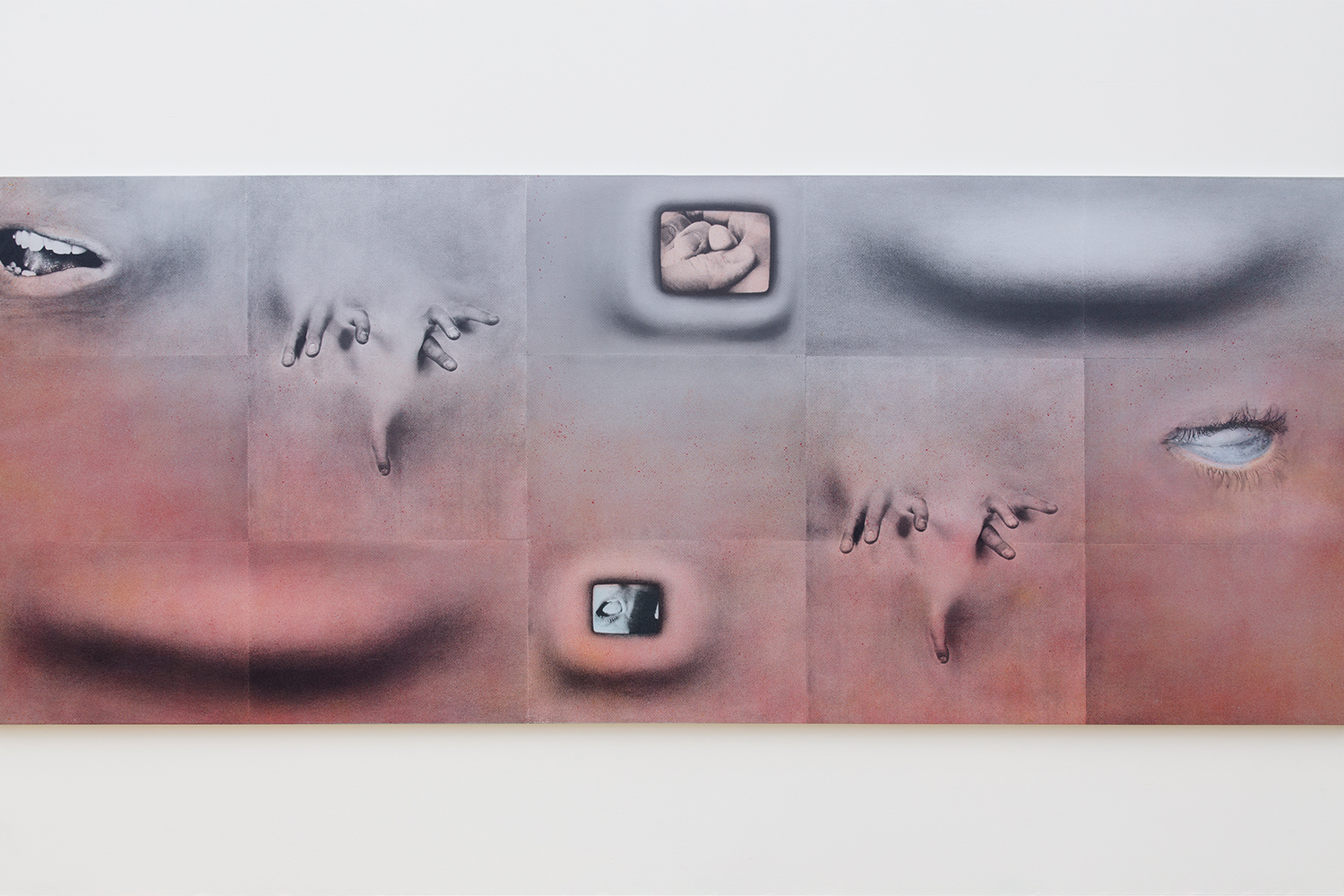

Intuitively, Hsu understood the folly of this fallacy (and, it should be noted, years ahead of critical correctives such as Hales’). His philosophizing through the body recast the notion of “interface” as a function of immanence rather than imminent transcendence. This is dramatized in a work like Fingerpainting (1994), with its grid-like structure and fuzzy, static-charged ground against which hands are being pulled into or pushed through. Free- floating mouths are echoed by organ-like monitor insets. But the movement on the surface is also rife with humor, dramatizing our anxiety as much as poking fun at it, as underscored by the title itself, which references the technique of silk-screening used here to anticipate or mimic the effects of Photoshop (which, it’s worth saying, would not become readily available until 1995).

Beyond Concrescence

This synchronicity between technique and technology has defined Hsu’s output from the 1990s to the present, unfolding in a way that almost approximates a seamless feedback loop. As he notes, “The congruence of technological media and the formal evolution has been a mystery to me as well. I never imagined digital imaging, Photoshop, 3-D printing, wide-format digital printing, the properties of silicone or bathroom tiles, as media, nor the iPhone or desktop computer. I developed them as a medium in pursuit of a sensibility I was intuitively seeking. Every technology seemed to provide an option I was looking for, in retrospect, but which I never imagined.”

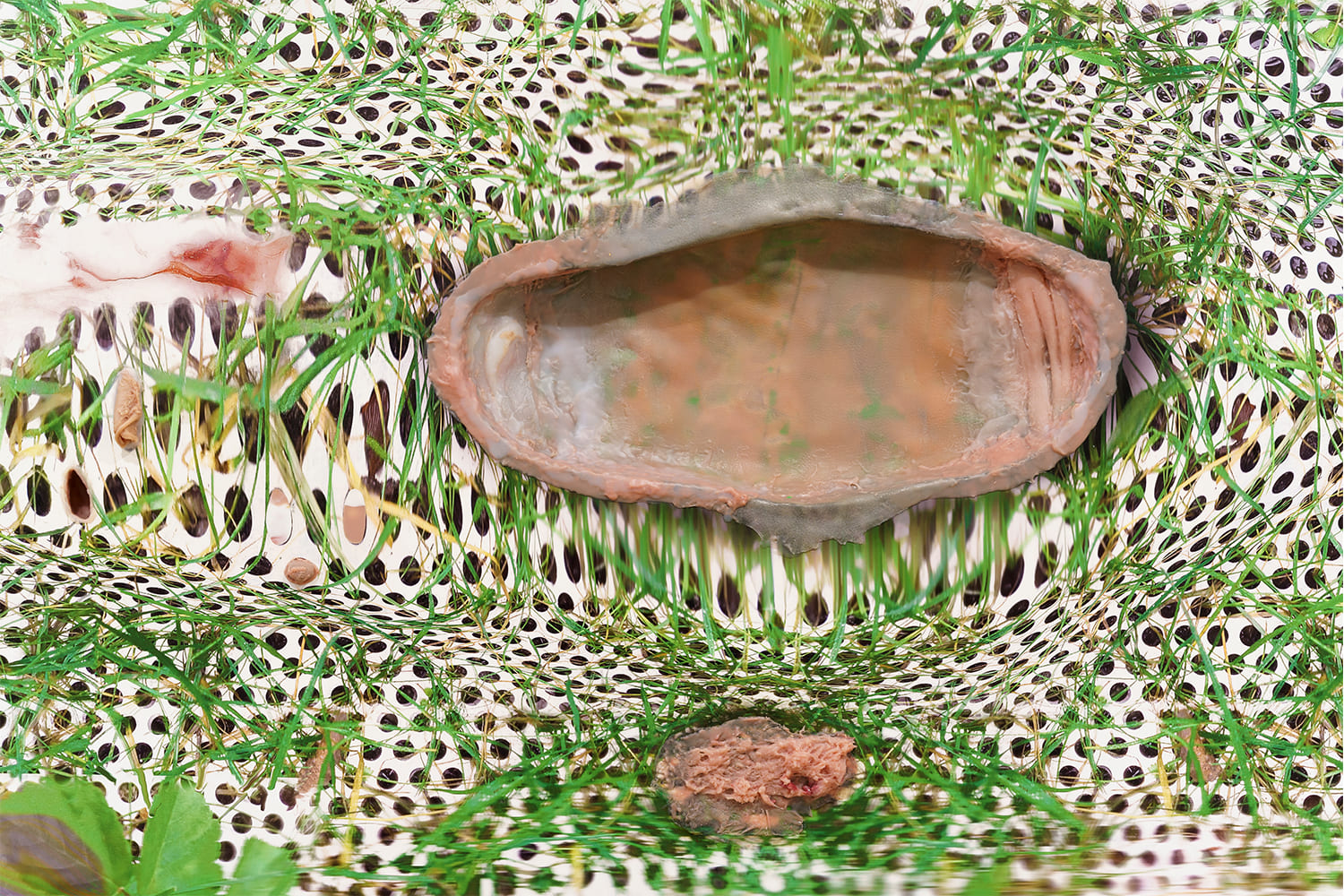

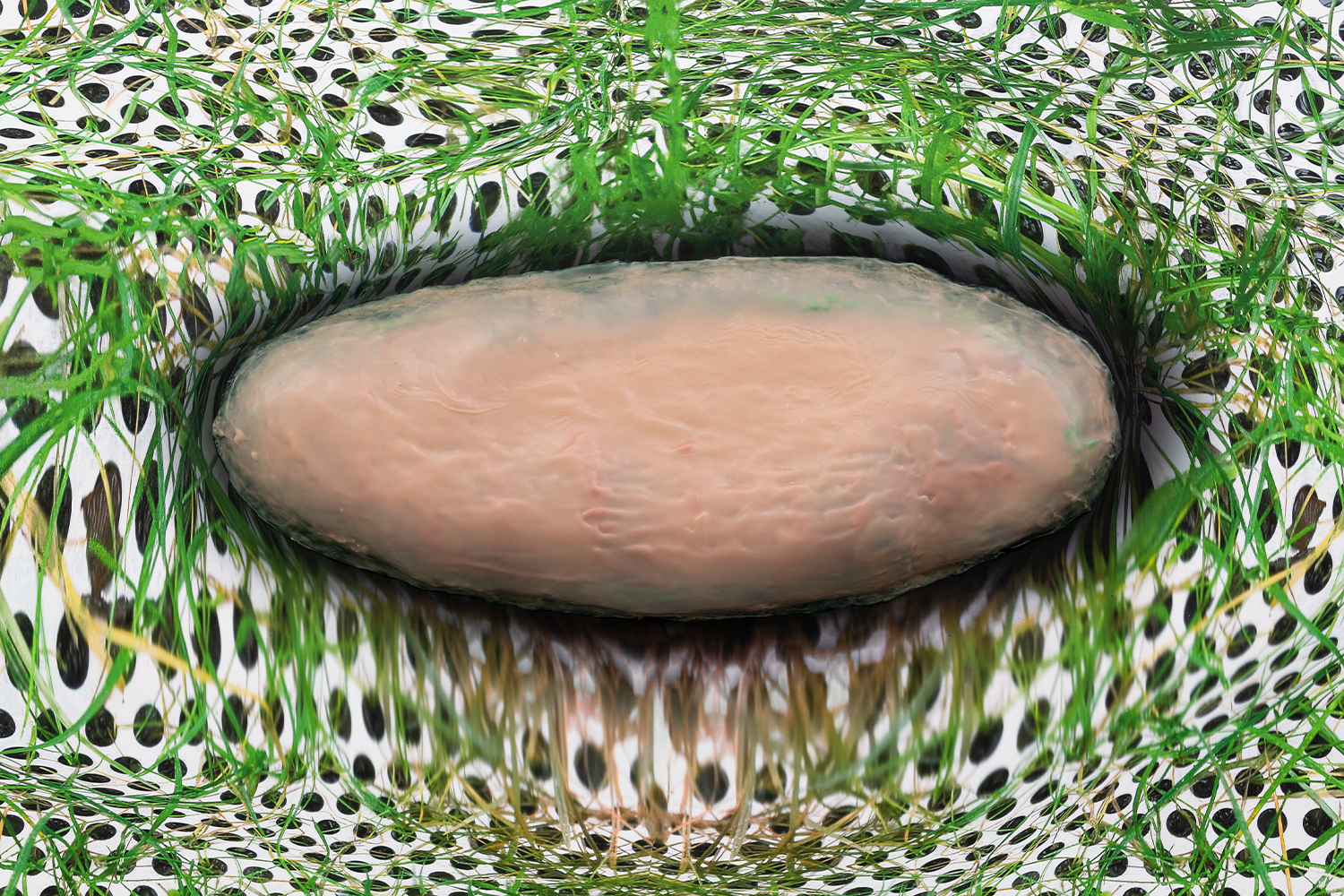

Prescience aside, this level of sync has freed up other avenues and registers for exploration, including fresh materials, like silicone, along with denser and more complex visual fields. It has also opened up space for the political — always an implicit subtext but not taken up directly, particularly post-2013, when the death of his mother led him to an archive of personal objects, among them family letters and photographs dating back to the 1950s. This trove of hard data filled in the emotional gap of displacement (his parents were prohibited from returning to China) as it registers on the individual level. Known simply as “The Shanghai Project,” Hsu embarked on a focused mission, activating links, reconstructing family lineages, suturing connections truncated by geographies and ideologies. The result is a body of work that is extremely personal but no less engaged with the technological — in fact, it is made possible by it. Take for instance Boating Scene Green (2019), a pastoral snap of a family outing on a lake, overlaid with distorted sim cards. Neither nostalgic nor sentimental, the work attests to absence even as it documents the attempt to reconstruct it through available means, including emails, Skype, and WhatsApp exchanges. In it history becomes a diffused thing, with scattered components hinging the personal and the political and always as an incomplete picture.

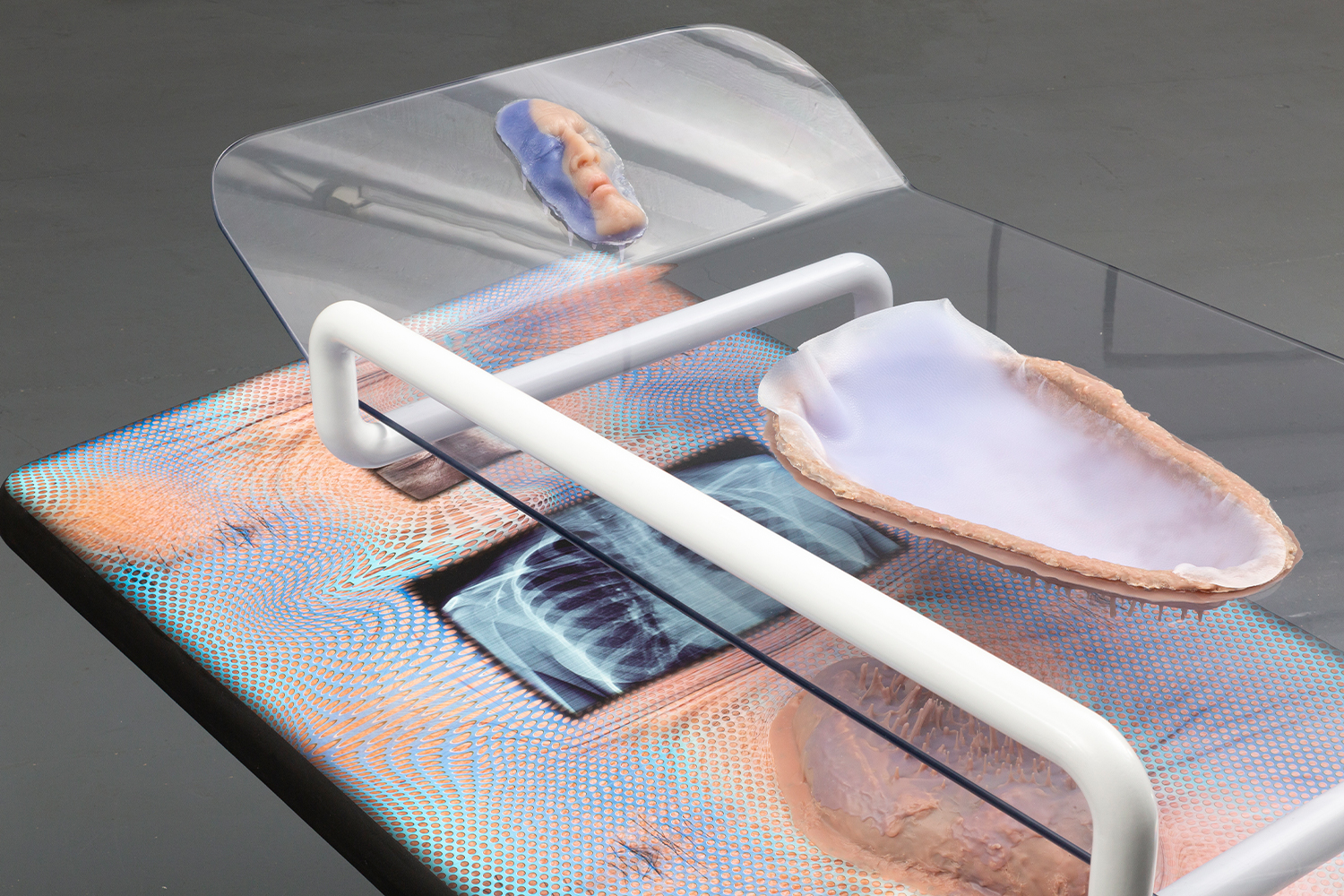

Affect emerges as the dominant tonality in these works. In doing so, it brings into relief a more specified body — not a generalized abstraction but Hsu’s very own, embedded in the particuliarities of his lived experience. This yielded the subtle poetry of his most recent solo exhibition, “skin-screen-grass,” which combined work from “The Shanghai Project” alongside a number of pieces that advanced fresh avenues of inquiry. Among these, Phone-Breath Bed 1, (2021) — a gurney-like sculpture that incorporates a face cast, torso X-rays, and fleshy drippings of silicone that can’t help but conjure the anxiousness of anyone living through 2020. There is also Spa (2021), a monumental multi-panel work memorializing the victims of the Gold Spa shooting. There is a radicality in the directness of the piece that also undercores the utility of affect as a vector into that which exceeds our understanding. As Hsu notes: “[affect] seems to be reaching for a kind of awareness of our emotional, psychological, and embodied processing, as an integrated response, which might help to identify, in some partial way, what is happening internally in this new interface we increasingly inhabit, between the body and technology.” He adds with typical forward-looking candor: “I am reaching intuitively, and perhaps I use the term too loosely, partly because I feel we may not have an adequate vocabulary to describe what we, as a species, are undergoing at this time in history.”