Racheal Crowther attempts to materialize the immaterial across her largely installation-based output. Recent work examines how the five bodily senses can be subliminally or unconsciously exploited to influence human behaviour. Crowther’s current area of research, developed during her ongoing Bétonsalon residency in Paris, has focused on scent as a carrier of information: how its molecular immateriality can be abused, by corporations and governments alike, to influence patterns of consumption, to inflict olfactory psychological violence, or to instill feelings of calm and reassurance. By and large against our collective wills, or without our consent.

Crowther’s 2025 exhibition, “Gebrauchsmusik” at Galerie Noah Klink, Berlin, intercepted openly accessible civilian airbands through an antenna installed on the building’s roof, amplifying these public-private radio transmissions into the gallery space in real time. Chatter from construction workers, couriers, and security guards — individuals involved in the day-to-day runnings of our cities — formed an imperceptible soundtrack of unseen (and formerly unheard) labor that Crowther accessed and evidenced for her viewers.

The artist’s interest in the imperceptible or immaterial extends, on occasion, to physical realms: inaccessible spaces no longer habitable and/or awaiting imminent demolition. The sites addressed in her work — care homes, psych wards, or houses of confinement — have a history as places of care or spaces of refuge for those who have been failed by our local councils, social services, and governmental policies. Crowther’s intervention into these spaces is minimal, but the ghostly hallmarks of the sites in question, their often hostile architecture, and sensory engineering carry through into her work, becoming actualized through the aesthetics of her sculpture, installation, and exhibition making.

Across her practice, Crowther examines how people, often vulnerable, are monitored under the guise of safe-guarding, and how the aesthetics and apparatus associated with places of so-called “care” maintain a palpable unfreedom.

Ben Broome: We’ve spoken in the past about information leakage in relation to your work. I remember you telling me about this moment in your childhood where you were able to eavesdrop on your neighbor through the baby monitor.

Racheal Crowther: My mum used to work night shifts at the hospital. I had a baby brother at the time, and the baby monitor would go in my room when she was at work. My bedroom shared a wall with the neighboring house and, because their baby’s monitor used the same bandwidth, I could sometimes hear the neighbors arguing or talking. I must have been ten at the time and, as a child, it felt very illicit to suddenly become privy to conversations I wasn’t meant to hear. I remember going to bed and almost longing to hear them.

BB Would you say you are drawn to this illicit acquisition of knowledge or information?

RC It’s not what’s illicit that I find specifically enticing but, across my work, I am interested in dynamics surrounding access.

BB Your “Managed Decline” series (2023) concerns physically inaccessible realms. As far as I understand them, they’re replicas of the steel doors constructed to prevent access to a building when it’s nearing demolition?

RC They’re replicas of real door covers commonly used in decanted blocks of flats. Sheets of mild steel are welded together over windows and doors, resulting in these haunting patchwork barricades. It’s a cheap security solution to stop squatting whilst a block is awaiting demolition. Mild steel is very reactive to its environment, rapidly rusting and eroding. Encountering hundreds of these door covers whilst walking down the corridor in one of these condemned buildings feels claustrophobic and violent. I won’t forget the pervasive smell of damp and rust. When I exhibited those works, some people immediately knew what they were looking at and others didn’t. Caregivers, people who have squatted, or those that had been displaced understood exactly what they were seeing. There was a shared understanding amongst those viewers.

BB Points of access or clarity in viewership is something that, at times, exists outside of your control. How do you reckon with unavoidable obfuscation in your work and exhibitions?

RC It’s a symptom of the parameters that I set up in my work, and something that I have no choice but to embrace. In Close Call Only (2024), for instance, you’re not really sure who’s speaking. Sometimes it’s just textual noise. It’s a frustrating work in many ways because it’s totally inaudible at times. You might hear a fragment of a conversation, but you’ll never hear the response. As soon as one transmission ends, it flits to another live channel. I wanted it to feel like something in flux; it’s completely reliant on the locality, the architecture of the building, and how I’ve programmed it.

BB One of the parameters of Close Call Only that is foundational to its functionality is the obsolescence of the technology that allows for interception. Do you purposefully use technology on the precipice of obsolescence?

RC I needed a scanner which had the capacity to intercept digital frequencies, like DMR and NXDM. So the scanner I used was actually from 2016. Before encrypted radio was introduced, these scanners had the capacity to listen to the police or emergency services. That isn’t possible now, because they run on an encrypted frequency called TETRA. You only get a jarring, high-pitched sound when tuned to a TETRA frequency; there’s no speech.

The main transmissions intercepted by the scanner were from the walkie-talkies of security guards, ShopWatch, couriers, construction workers, and air traffic control. Radio technology feels obsolete now as people can connect through their phone, Instagram, email, but there was a time when that sort of communication wasn’t possible. Radio was how people would learn information. It was a source of news, even a war-time warning system.

BB You speak about “materializing the immaterial.” How is this realized in your work?

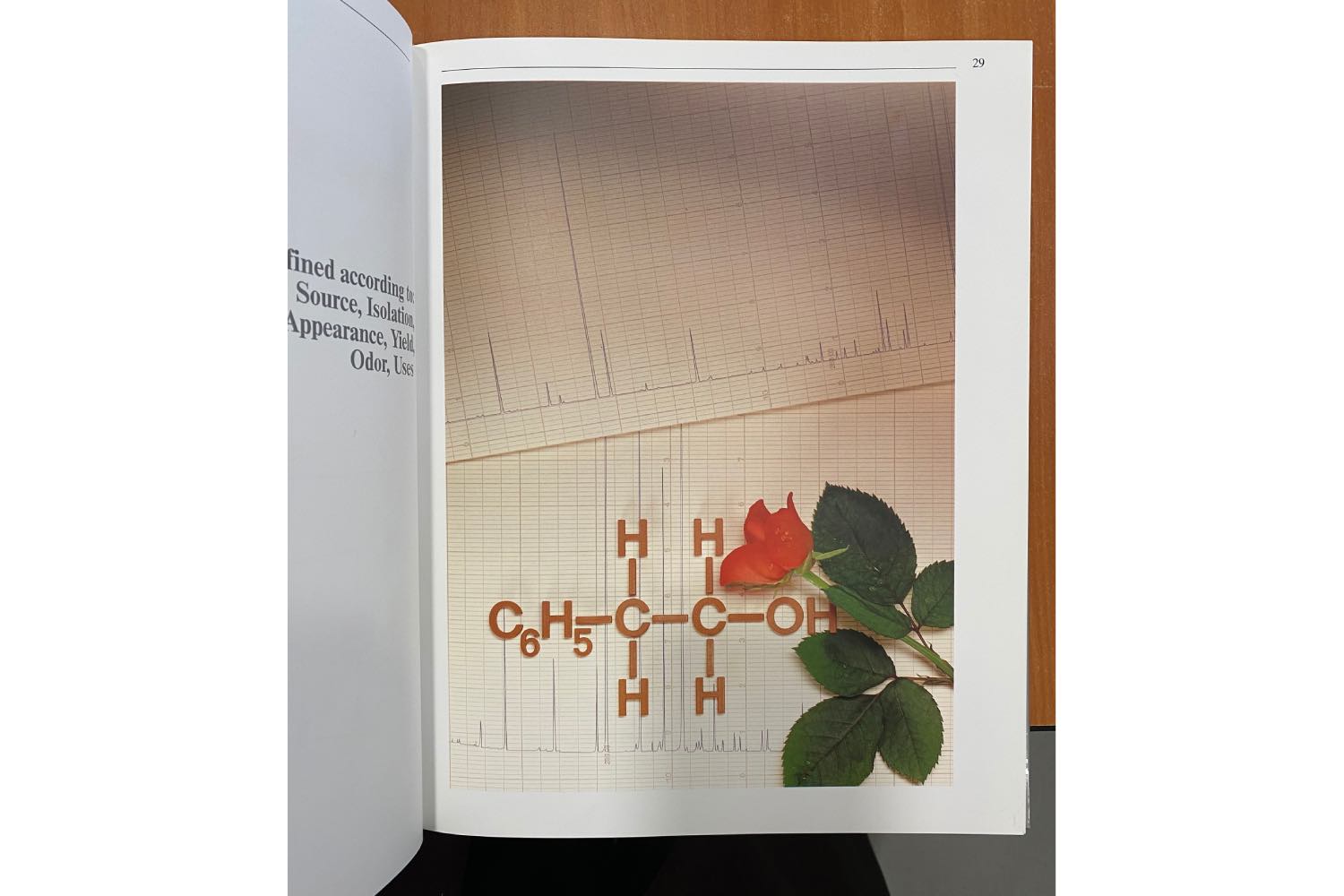

RC Both sound and scent are invisible carriers of information. The show we made together, “Gebrauchsmusik” (2025) at Galerie Noah Klink, Berlin, relied solely on the electromagnetic spectrum to function. Scent is molecular, but it shares an intangibility. Smell, like sound, can be a carrier of information. It’s a vessel, it’s molecular, but it also exposes truth. We use it as a kind of safety device: to know if food has gone off, the smell of smoke or of gas. There are certain smells our body knows: If we smell rotting flesh, that’s a signal. We are wired to find that repulsive. Visiting the Stasi Museum in Berlin, I learnt about the Stasi’s infiltration of the radio — there’s such a long history of interception. They also kept a scent archive which they’d used to train sniffer dogs. Olfactory surveillance as a method of tracking or identifying has been the subject of much of my recent research.

BB In your work with sound and scent, there’s a methodology in installation that influences a choreography of how we navigate these spaces. Behaviors are being influenced by the work. Are these dynamics you consider in conception?

RC I’m interested in the architectural engineering of controlled spaces, particularly in houses of confinement. In these spaces, a lot of thought goes into the manipulation of behaviors through sensory engineering. The feeling of a room will impact a person’s behavior within it. A police interview room, for instance: the furniture is drilled into the floor and you’re aware that you’re being recorded. It’s a nerve-wracking experience being in one of these rooms, even if you’re not being interviewed. It’s a space that has been engineered to make you feel that way. The anti-ligature cabinet that I used in the Gebrauchsmusik (2025) installation: I’d seen those cabinets in hospitals, psych wards, and youth detention centers. The vending machine that I used in Mean time between failure (2023) implies a place of waiting. These objects and architectural elements that I choose to bring into the gallery environment are loaded materials to me.

BB You recently wrote on the Trafford Centre in Manchester for TON Magazine. Would you say that the architecture and interiors of that space were engineered to influence behavior?

RC: I grew up in Manchester, so I’d seen the Trafford Centre become what it is. The property developer behind the Trafford Centre, John Whittaker, was inspired by Vegas malls. He visited all the big supermalls for inspiration. For the interiors, he used a pastiche of classical architectural styles and eras in the hope that it wouldn’t date. Of course it’s dated: the food court was designed to look like a cruise liner “travelling the world.” KFC is embedded into an Egyptian temple complete with hieroglyphs; McDonald’s is a Moroccan souk. There’s no natural light in the food court, only a painted sky with fiber-optic stars. The light supposedly changes to mirror the outdoors, but it always feels very dark. This is a tactic borrowed from casinos where no clocks, no lights, and certain kinds of ambient fragrancing keep people in the space and keep them spending. These are subtle sensory engineering techniques that influence our behavior in these spaces of consumption.

BB You mentioned that the developers were drawing from the aesthetics of the Vegas strip, which in turn borrow motifs from ancient Rome or Greece. A false translation of culture occurs.

RC Disneyland employs the same methodologies of time-space compression in their architectural engineering. They’ll take gothic spires from Prague and German castle walls, compressing them into architecture that is hard to locate geographically or historically. They call this “reassurance architecture.” When you’re in Disneyland (I went recently) there’s music playing in each zone. Your time there is literally being soundtracked. Disneyland is such a sensorial head-fuck. There are so many smells that are definitely being amplified. There’s no way those dry cakes smell like what I’m smelling!

BB Gebrauchsmusik translates literally as utility music: music designed for a purpose other than enjoyment. Do you think that scent can be used in a similar way?

RC Ferrari impregnates the leather they use with “new car smell.” The leather doesn’t smell like that. M&M World, Subway – so many businesses use smell to influence buying behavior.

I recently purchased a scent molecule that smelled just like the dentist. I went to the dentist a few days later and was smelling that exact same smell. Are they just pumping this out so it smells clean? Because no cleaning product smells like that. It smells sterile but it’s obviously not… someone’s outside having a cig, we’re by a main road with the door open, there are grubby magazines everywhere.

BB We expect from these places of care — the dentist or the hospital — a level of cleanliness. Equally with perfume, we expect it to smell opulent. We place our hopes, dreams, or aspirations onto scent. Do you consider aspiration within the context of scent?

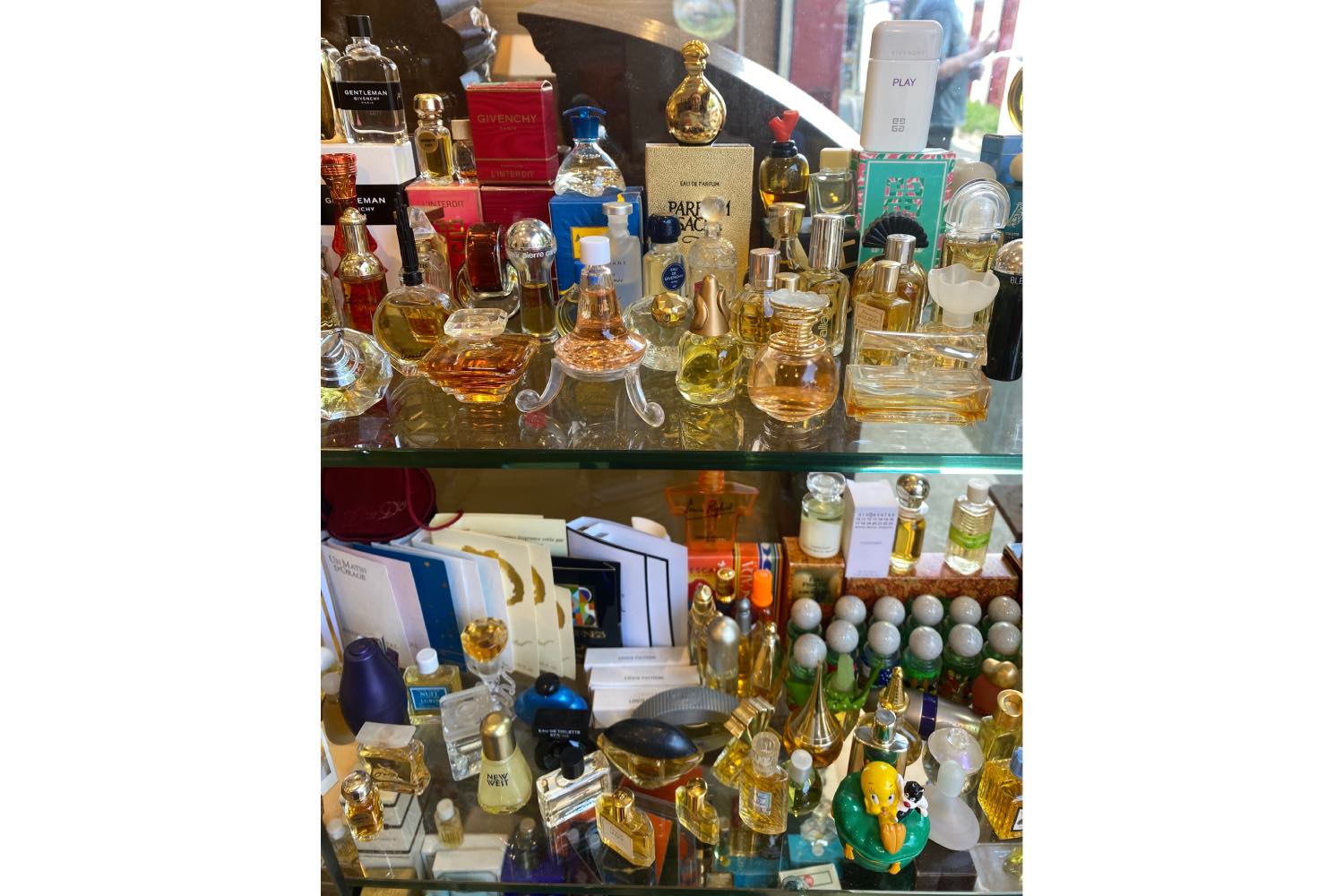

RC Before social media, celebrities would bring out their perfumes as a way for fans to access them. A fan could be brought closer to Britney Spears or Paris Hilton through scent: “This is what they wear, this is what they smell like.” When Ferrari brought out their first cologne, the owner made a statement, saying, “This is for those who can’t afford the car but want to buy into the lifestyle.” It’s just a way to make more money. Olfactory aspiration is something I was thinking about when writing an essay for Montez Press, which began by recounting the Salisbury Novichok poisonings by Russian agents. The single fatality, Dawn Sturgess, was living in a homeless shelter with her partner, who’d found a bottle of Nina Ricci’s Premier Jour perfume in a charity shop donation bin. He saw that branding, he saw the bottle, he recognized it as something valuable, and he gifted it to his partner. We know now that the bottle contained the Novichok nerve agent, which Dawn Sturgess sprayed on herself and later died from. The intended targets were Sergei and Yulia Skripal, who both miraculously survived. It was the aspirational qualities of perfume that led to Dawn Sturgess’s tragic passing. The terrible irony is that poisoning and intoxication are used to market perfumes. Dior’s Poison actually contains notes of bitter almonds, the smell of cyanide. These aspirational qualities are also amplified through advertising. How do you sell perfume to someone? People can’t smell it through the TV screen or an image. The visual volume is turned up in every way possible; perfume adverts sell you a dream.

BB Walking through Paris the other day, we stopped at that perfume shop because you were dying to smell Rihanna’s perfume. Was it the artist in you who wanted to smell that?!

RC Oh, that was just for me babe! I’d seen videos of people talking about how good Rihanna smells. It was recently revealed what her fragrance was: Love Don’t Be Shy by Killian. People go crazy for it. When we walked past the Killian store, I had to smell it!