Repetition is the stuff of everyday life; it’s what we do. Even when I’m mixing it up, there’s a subjective equation whose result is the same. But accidents happen – slips of the tongue, to say the least – and it is the specific way I at once produce them and respond to them that shapes my life. In Lacanian psychoanalysis, repetition has two forms, borrowed from the ancients: tuché and automaton.1 We are bound to automaton, which describes an almost endless coming back to the same signs again and again, a kind of senseless loop whose course is predictable once established, determined as it is by the search for its own stability. The other kind of repetition, tuché (in which one cannot help reading the comical retort to a point well-made: touché!), is a kind of encounter. We could even say a surprise. Having perhaps more to do with contingency, this second repetition is nonetheless a kind of contingency that must be seized.

If sculptures are serial objects in three-dimensions (I’m thinking of technical reproducibility), Olga Balema’s oeuvre is exclusively sculptural. The works also call for the vocabulary of installation art in their effect on the surrounding space and dependency upon it. Relying on and transforming context has become a cliché. What serious art hasn’t been made aware of its surrounds and its conditions since Minimalism (aka literalism) claimed the space and the viewer’s experience alike? A distinction is crucial, though: literalists disdain sculpture — and all composed, figured art — because composition implies a gap, a part of which they are not in control.2 In other words, there are two ways to work with the surrounds. The first (literalist) totalizes and seeks to overwhelm, and creates indifference to being looked at through pronounced knowledge about itself; the second (materialist) relates and questions, looking at it creates difference because the work is the residue of a process partially unknown, even to its author.

It is the exception that proves the rule. Balema’s practice once included video — she made Squeeze Through (2012), which animates Bella’s vampire transformation in Twilight across five screens — until she found a way to satisfy time and seriality within sculpture itself, notably around the period of her exhibition “What Enters” (2013) at 1646, The Hague. Bits of metal, textile, and other unspecific objects are encased in low-lying transparent PVC rectangles about the size of single mattresses, filled with water and glued shut. The chemical reaction of water and the other contents inhere these works with a kind of dramaturgy, one in which the artist sets the starting point but cannot know exactly what will be visible as time passes.

Let’s hazard a minimal definition of “time-based” as works for which the components light, movement, and duration are decisive, whatever their technical support. This expands the definition of time-based as a descriptor of all film and audiovisual art to encompass not only performance art but also some sculpture. The late writer and artist Ian White might have gone so far as to call such practices “expanded cinema.”3 Without overplaying the use of classical medium distinctions in apprehending visual and plastic arts, positioning a given practice in a field helps to see where the juxtaposition of disciplines does justice to a practice and its transmission, while bearing in mind Joan Copjec’s warning that “the perfection of vision and knowledge can only be procured at the expense of invisibility and nonknowledge.”4 I use categories of knowledge like sculpture, installation, and time-based in order to contend with the fetish for category-busting becoming its own kind of perfect knowledge. This would be the point where all the prefixes for “disciplinary” (inter-, multi-, anti-, un-, etc.) culminate in a refusal to say anything.

It’s in this spirit that I say Balema makes sculptures, with the footnote that they contain something of the time-based and that this can be elucidated through the concept of repetition, to be understood in a vacillating manner, at once physical and semblance, necessary and contingent, substantial and circumstantial. In this light, I will mainly focus on two bodies of work, “Loop” (2023–ongoing) and “Brain Damage” (2019), and a selection of the artist’s statements, which help construct this argument.

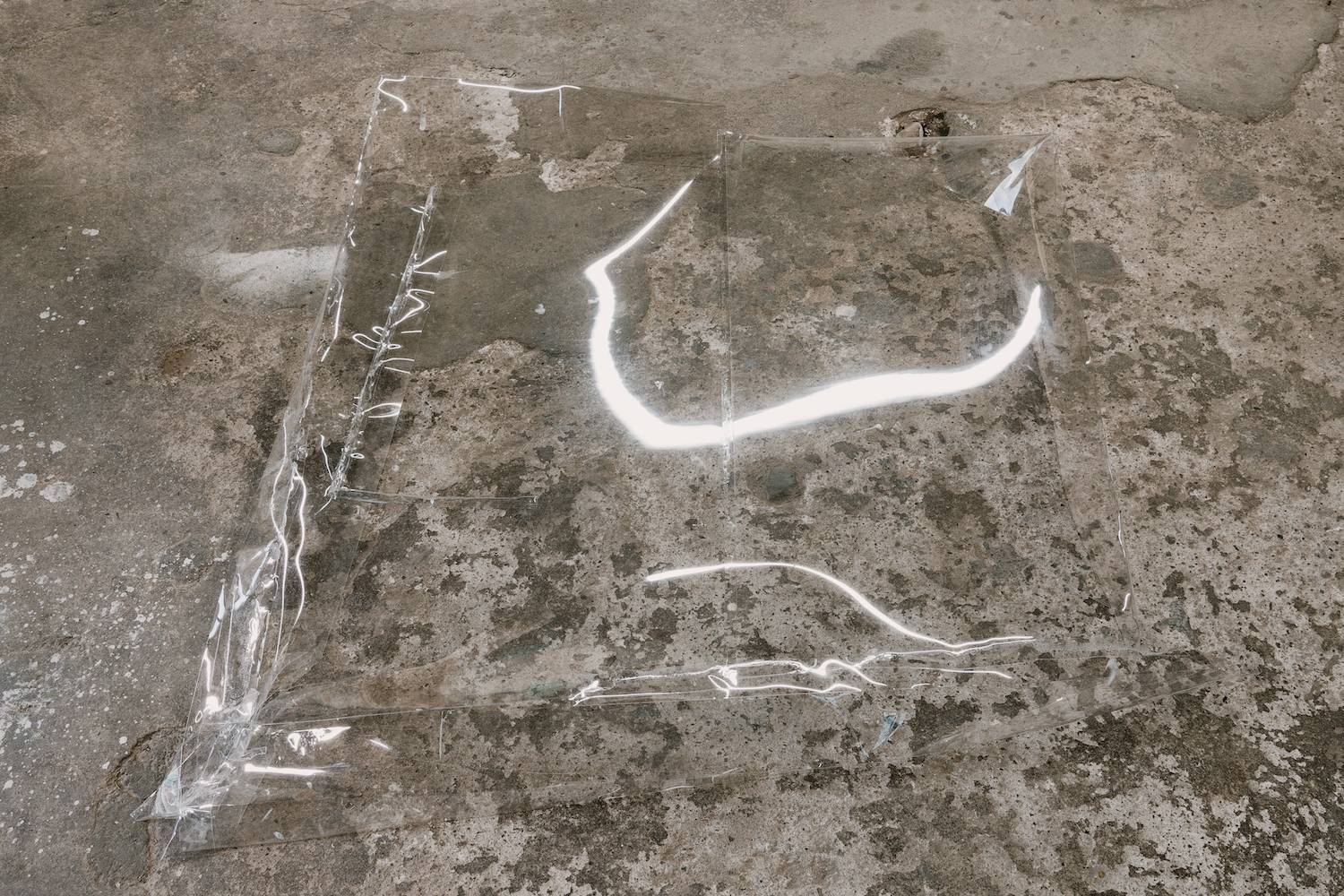

The ongoing series of sculptures called “Loop” began in 2021 without a title and has comprised the majority of Balema’s production since then. These works are made of transparent polycarbonate, thin clear plastic, that is folded, bent, cut, and glued — sometimes standing alone, sometimes using a plinth, wall or corner on which to lean. As vessels unable to contain (if filled they would leak), sometimes they seem to billow, sometimes they buckle from their angular edges and corners exerting pressure on the surfaces yet failing to hold them totally straight. Gravity is taken into account and is an agent in their composition, as is the floor itself, which seems to exert upward pressure on their gentle bodies. “Loop” is like a lowest common denominator of sculpture—volume, surface, and gravity—and, as such, resists speaking for sculpture, subtracts rather than adds to it. It is in this sense that we must understand the work’s transparency not via the fantasy, whereby there are no secrets and we might see all as it actually is, as the ideology goes,5 but rather exactly as a symbol for our lack of transparency to ourselves.6 To that extent, what might be represented by “Loop” is precisely your own looking coming at you from outside.

This is why we could say “Loop” is social. In relation to earlier, untitled water-based sculptures, Balema wrote: “interiors becoming exteriors becoming interiors.”7 The latency of repetition and a sense of circular movement mark the poetics of the phrase, touching on the Lacanian concept of “extimacy.” Extimacy refers to the discovery “that what appears to be exterior is actually interior, and what appears to be my most interior self is foreign to me.”8 This takes us back to the idea of transparency, and the erroneous equation of transparency with vision, recalling that what is the most intimate to me is, at the same time, the most opaque.

What perhaps goes without saying, but is worth articulating, is that “Loop” reflects everything around it. How it appears changes as you move and as the light moves. If the ground is wooden, concrete or grassy, if the walls are white, brown or inexistent, if there are windows or not, if the sun is shining and the time of day, which way the shadows fall, if there are other people in the space or not, if there is artificial light above— all this changes something in their appearance. Still, reading “Loop” too much through the changing surrounds, shifting light and movement of viewers feels facile; overemphasizing these elements promotes a kind of grandiose pedantry of mind that trivializes the encounter with the object.

I recall Balema’s evocation of a “novel without a plot,” namely Joris-Karl Huysmans’s À Rebours (1884) [Against the Grain or Against Nature], which is precisely an exercise in representing the passage of time in which no encounter takes place to break into the decadent repetition, even failing health. In art, looping isn’t just a technique for compulsively repeating the same to ensure homogeneous viewer experience. It can also be a technique to punctuate time with difference by bringing the machine’s repetition into contact with circumstance (art meets exhibition meets visitor meets public). What is produced is a kind of syncopation between the two terms, which is what grounds the work’s appearance in something that is by definition unrepresentable.

We could say “Loop” goes against the obsessive demand for novelty by appearing – and, in fact, being – persistent. Bear the two kinds of repetition in mind: one is the endless flood of commodities to break down dams and enlarge the demand to enjoy, the fantasy of no limit; the other is a kind of spanner in the works, a chink in the chain, that slows things down. Not giving up on saying that one thing, and bearing oneself with absolute fidelity to that thing, despite, and probably, because you have no idea what the consequences will be.

A title is telling. In 2017, a group of sculptures from “Loop” were shown at Hannah Hoffman in Los Angeles in a solo show named “Loon.” This kind of wordplay and wit is characteristic of Balema’s relationship to language. She said in an interview “there is no outside of language for me,”9 a pretty succinct definition of Lacanian psychoanalysis. If I interpret “loon,” it evokes the “Looney” of Tunes fame but also the word for “pay” or “wage” in Dutch, whose country Balema lived in for two years. It also insists on a minimal difference from “loop,” a gap being formed between “n” and “p,” with no explanation to cover it. Other titles further illuminate Balema’s materialist vocabulary: The Distance (2025), Computer (2021), Formulas (2022), Threat to Civilization (2015), Blasted Health (2016), Cannibals (2015), The third dimension (2013), and Brain Damage (2019).

Disarmingly, Balema’s work distorts my usual looking in relation to the gallery space, especially through enhancing attention to the floor and footing. This was my experience at Bridget Donahue, New York, in whose space Balema’s work seems particularly at home, held by the wooden floor. “Brain Damage” is an astonishing series of sculptures, a network of white trouser-elastics placed, knotted, painted, and stretched at ankle height across the gallery floor with the momentum of nails and the wall, establishing contours and intersections just above the ground, some taut, some loose. “Brain Damage” is a surprise, its appearance modest and at the same time grave, a rude awakening. Has she really done it? Is this sculpture? It’s certainly not Fred Sandback’s geometrical threads, though it has to be mentioned. There’s something about the poorness of the material, the tokenistic way paint is applied, the loose ends, the placement so low it’s almost invisible, the likelihood of being trodden on, tripped over: all of this accentuates Balema’s humor describing the work as her foray into painting.

I can’t help but think of Catherine Malabou’s sidelining of the elastic (a term used by Deleuze) in favor of the plastic (a term used by Freud), as well as her profound meditation on brain damage in her book-length essay Ontology of the Accident (2009). There, brain damage is addressed — perhaps for the first time — as an object worthy of philosophy, and as such, as radical discontinuity, something which as a “blind event” cannot be integrated retrospectively into experience and allows no explanation.10 Musing on the figure of Marguerite Duras in this context, Malabou writes of the rhetoric technique asyndeton, which is obtained through suppressing links and causal connections: “It belongs to the class of disjunctions and it telescopes words, which come one after the other, one on top of the other, occurring as what amounts to so many accidents … Use of asyndeton may cause interpretative difficulties, confusion.”11 And later, still referring to the literary technique, but also, perhaps to the author, who is like an artist: “The subject finds herself at the end, as if emerging from her accidents, from her own destruction, which has no meaning and comes out of nowhere.”12 For her part, when I ask Balema about the title Brain Damage, she intimates it is what making art can do to you.