My lone star is dead — and my bespangled lute / Bears the black sun of Melancholia.

— Gérard de Nerval, El Desdichado (The Disinherited)

A black sun is a negative brightness, a void. It represents the melancholia that grips a person, that runs in an undeniable rhythm, a pulsation that churns regardless of the physical world. It is, as Julia Kristeva writes, “an insistence without presence, a light without representation: the Thing is an imagined sun, bright and black at the same time.” The black sun radiates through and around all things, its rays permeating bodies and producing not energy but lethargy, silence, and death. Mire Lee’s installation Black Sun at the New Museum is one of these things, a chamber populated by objects and kinetic machinations, which are themselves a persistent churning in visible radiation and audible manifestations.

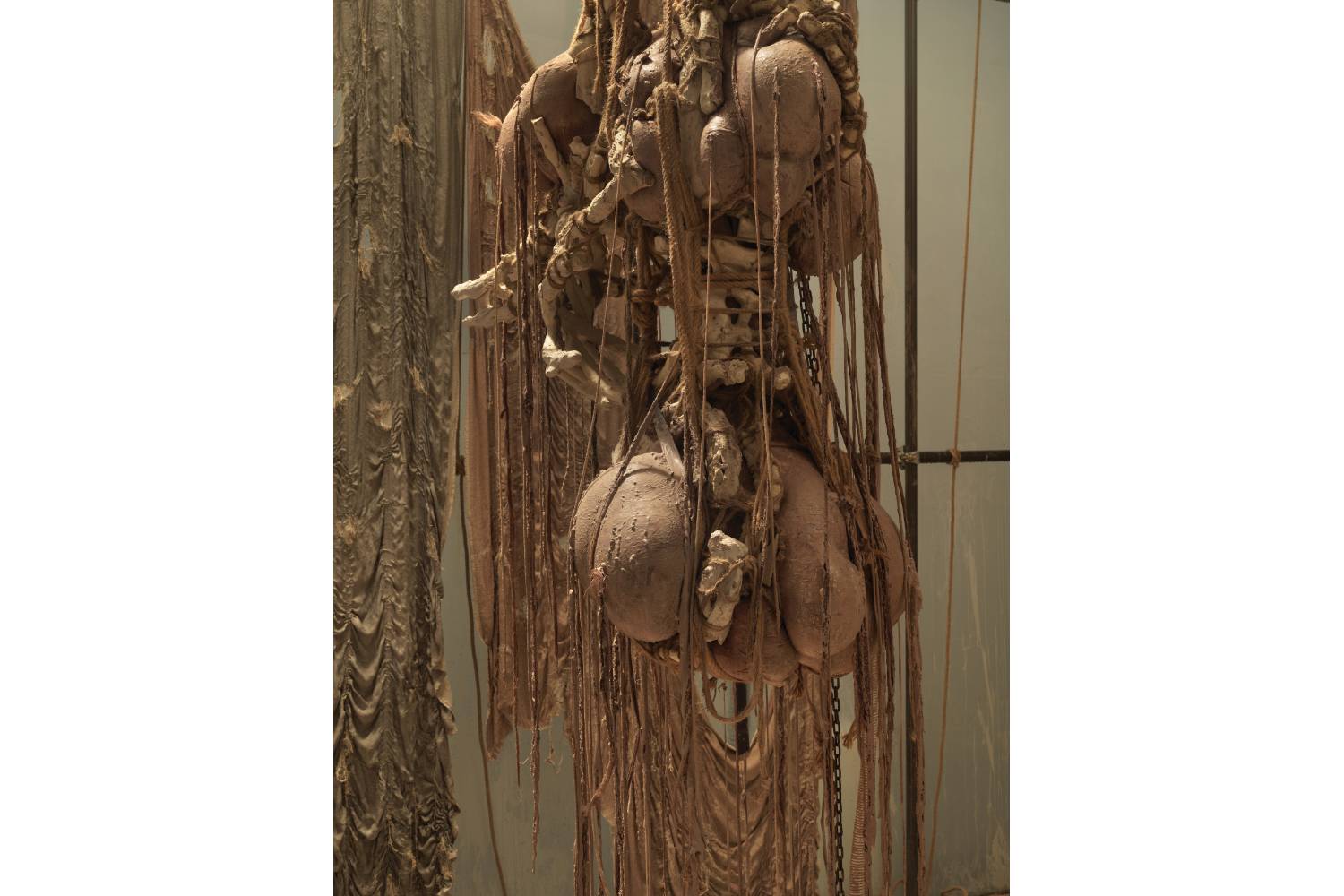

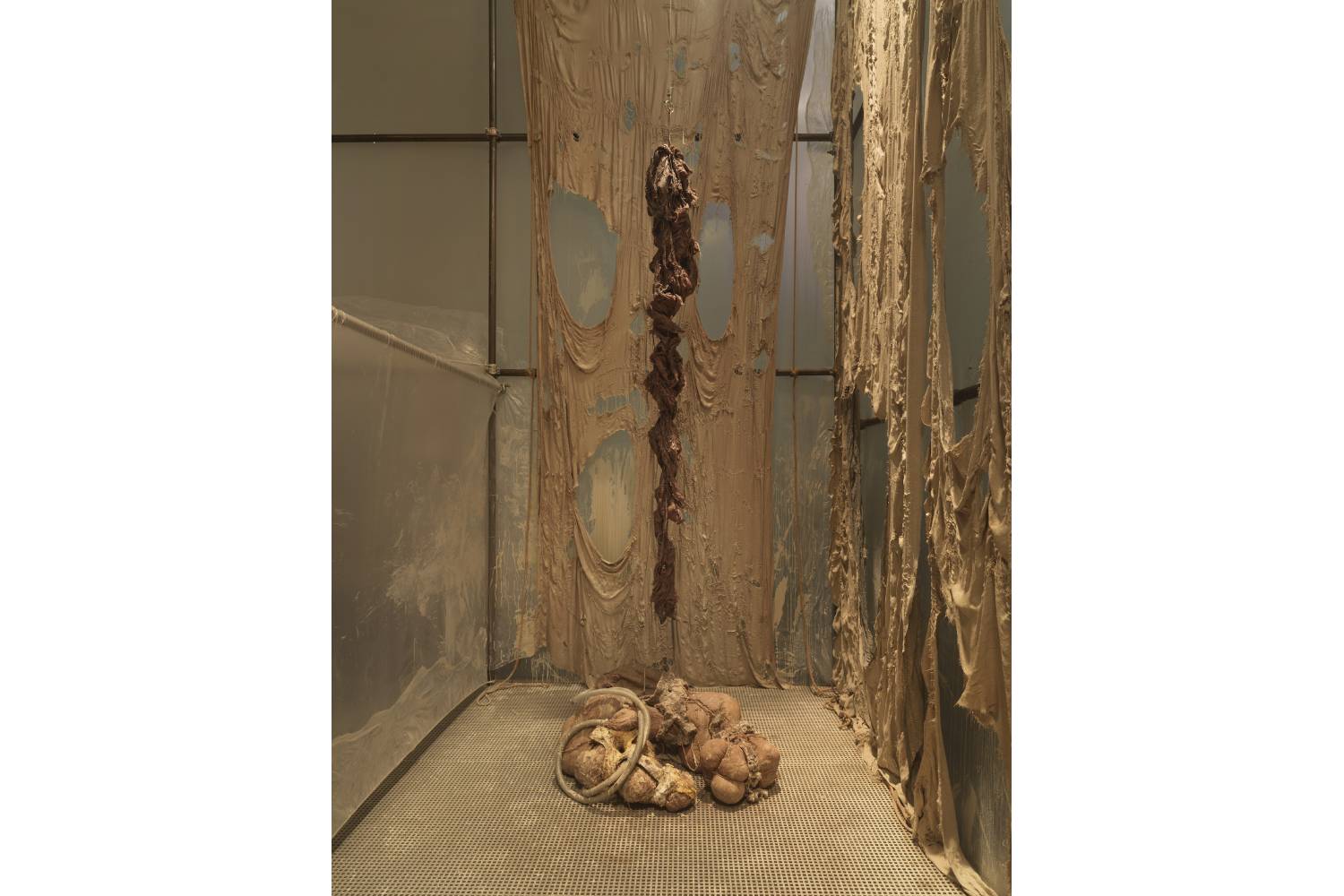

Lee’s work embraces an aesthetics of putridity that belies its true nature. To enter this chamber, one must walk up a ramp and through plastic hanging curtains, the type one finds in industrial slaughterhouses. It is an encapsulated scene set off from the rest of the museum that is altogether a new place, a reddened wet bowel not always achievable in a museum environment. Muck and mire cover the floor, the walls, and the objects, and feel bonded to the hydrogen and oxygen that is the air. It is a space that feels as if it should be cold while looking warm, with red and brown and yellow casting a hazy scene. Viscera — including bulbous internal organ-like bags and rope tied around bone-like armatures made from fired clay — are immediately visible. Various rope sizes entangle the entrails and entwine the calcareous structures, creating a tangle of knots, bones, and organs. Yet I can see a meshed fabric and even stockings, which I initially mistook as gauze. Black Sun: Vertical sculpture (2023) hangs from chains over a small pit into which liquid clay drips. Ribbed tubes carry the viscous substance to the sculpture. Dripping can be heard, and the iron-rich smell emanates throughout the space. There is a humidity that aligns with the sight and sounds of the work. To the right, Black Sun: Horizontal sculpture (2023) sits in a slanted pit, rising, at an angle, out of clay slurry. It is a scene of both gore — bones coming out of sludge — and beauty, because, as Kristeva writes, “beauty emerges as the admirable face of loss, transforming it in order to make it live.” It is what we might call a contradictive ritual display, the humming of dread that billows into beauty.

Pumps and motors whir throughout the space, the sound bouncing around and off the metal scaffolding that structures the walls, themselves backed by a frosted acrylic smeared with the clay mixture, dried. Draped fabric — ripped, torn, shredded, weighted down, it seems, from being dipped in clay — hangs from rods near the ceiling. They double as curtains and animal skins, albeit shredded. Each panel, if we may call them that, has a different tonality of earthy brown, some lighter, some darker, some with a more prominent tinge of redness, thus displaying the tonal range of the earth’s browns from orange to red. Lee’s Black Sun: Asshole sculpture (2023), a bowl-like basin sitting on the floor with a pool of clay slurry, rests on the floor in an alcove beside the entrance; on the opposite side are a triptych of sculptures, two laying on the ground like entrails and a third hanging overhead. It is easy to think of these objects as disemboweled creations, yet the smell doesn’t disgust. It ties us, as humans, to the work in an ancient and cosmic way. This is the semiotics of the work, an aesthetic of putrefaction that points to a celestial realm beyond sight.

Kristeva writes that “the ‘Black Sun’ metaphor fully sums up the blinding force of the despondent mood […]. It changes darkness into redness or into a sun that remains black […] but is nevertheless the sun, source of dazzling light.” Lee’s Black Sun exudes a heavy melancholia turned inside-out, disembodied. Like Kristeva, Lee is chasing a language to be learned beyond — or perhaps in spite of — its pathological treatment. Here the contradiction in sensorial and conceptual elements illuminates Kristeva’s, and by extension Lee’s, black sun. As viewers we are stepping into the interiority of a black sun, with its repetitive rhythm of sight, sound, smell, and movement, that is both Lee’s and ours. In so doing we see it for what it is: an earthly, grotesque, failing yet prevalent viscus of flowing fluids that is our collective self-portrait.