Originally published in Flash Art no. 311 November – December 2016.

This past summer, during Atonal, a yearly festival for experimental electronic music held in a former power plant in Berlin, my friend Daniel Fisher, the DJ Physical Therapy, posed a surprising question:

If all power plants are now clubs, where do we get our power from?

The following week, the question remained unanswered as Berghain — the seminal Berlin club also situated in a former GDR combined heat and power plant — was struck by lighting during one of its Saturday to Monday Klubnachts. The building’s air conditioning switched off for several hours, raising the interior temperature to a record height while the club’s cavernous main space was lit by glaring emergency lighting. However, the club wasn’t closed. The crowd remained unfazed, if even less clothed than usual.

It is ostensibly funny how power plants and factories have assumed a function — the club — diametrically opposed to their original use: dissipating excess energy through physical and affective work without obvious utility, such as dancing, the chemically accelerated depletion of dopamine and serotonin stocks, and nonreproductive sex. But only ostensibly, as today we live with an energetic surplus so far beyond what we require for survival and reproduction, that the vast majority of human activity is devoted to pursuits that fall under the categories of ritual and ceremony: the seemingly irrational sacrifice of time and resources for no obvious gain.

If the pointlessness of clubs is comical, so is pretty much everything else we do.

Maybe the power plant question doesn’t warrant a “serious” answer (which would only be disappointing: not all power plants are in fact clubs). But power ≠ power. So what is the power situation of clubs?

Buildings are an archaic technology, and constructing them requires vast amounts of energy to pile the necessary atoms on top of each other. Thinking about the incredibly limited amounts of energy available in pre-fossil-fuel civilizations — in which any yearly surplus was negligible, and in times of famine even negative — it is almost beyond comprehension how humanity managed to erect its greatest architectural achievements, from the Pyramids to Europe’s gothic cathedrals. Ancient civilizations, or the power circulating through them, clearly knew how and what to prioritize: dissipating the populations’ potentially dangerous excess energy through the building of grand structures, which took decades at a time, and the subsequent rituals that these structures housed. It’s not so different today.

Our most monumental architecture is realized through nondemocratic forms of power — from the Gulf States to Turkmenistan to Shenzhen — whether autocratic, fascist or financial.

Authoritarian regimes are hardly known for their majestic club architecture; the categorically wasteful nature of clubs lies at odds with their reason for being. But neither are liberal democracies. Instead, clubs largely occupy — almost always temporarily — the pre-gentrified leftovers of industrial civilization. This is largely due to economic necessity, but also because club culture cannot escape the architecture hard-coded into its DNA. The Warehouse in Chicago, the club that gave house music its name, was literally a warehouse. Paradise Garage, the club that gave garage music its name, was literally a garage building in pre-gentrified, Jane Jacobs–era Greenwich Village. (Or on a larger scale: the Thatcherite industrial wastelands to be occupied once acid house landed in the UK in the late 1980s; or freshly unified, scarred Berlin in the early 1990s.) This canonized history has lent club culture a general aesthetic disposition bordering on a fetish toward ready-made, found space: a kind of nomadic architettura povera.

The inclination is amplified via a widely held commitment to a cult of material authenticity (hardware instruments, vinyl, moist concrete walls) — somewhat paradoxically, considering club culture’s dependence upon artifice and the synthetic in all of its other aspects.

While the fleeting, temporary status of clubs in space is taken almost as a given, the very same leftover structures that they occupy are being rebuilt, rebranded and remarketed through the incessant process of gentrification. The House, The Store, The Diner. The nomenclature of present-day gentrification — ironically mirroring the naming format of the Warehouse and Paradise Garage — and its chosen aesthetic register, contemporary conformism, is obsessed with the authentic histories of spaces, as long as its low income, black and brown subjects are displaced or firmly situated in the past.

Indeed, one cannot talk about the history of club culture without talking about gentrification in multiple guises.

Firstly the gentrification of the club itself: from a primarily queer, low-income, African and Latin American space, culture and industry in the late 1970s and early 1980s, into one by the 1990s dominated by white, straight, affluent men. Secondly as an ostensibly nonproductive, even socially corrosive, activity that is a repeat victim of inner-city gentrification driven by both private and public interests that systematically ends up dislocated or closed down. And thirdly, in its most sanitized and whitewashed forms, as a driver of gentrification itself, as a strategic weapon of “placemaking” — but then only as a temporary, cringeworthy “pop-up” program to be displaced at a more mature state of the process.

Photographer Giovanna Silva’s recently published book Nightswimming documents club spaces across Italy, Berlin, London, Barcelona and Paris. The book, published by the Architectural Association–affiliated Bedford Press is a continuation of a project by Silva and Chiara Carpenter developed for the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale’s third main exhibition, “Monditalia.” It is also a contribution to the rapidly expanding body of work in which the architectural gaze goes clubbing.

Nightswimming is not an exhaustive visual survey of every relevant club space of the mid 2010s. It focuses — in a way that does not seem deliberate — on predominantly white, straight spaces (I couldn’t find one black or brown face among hundreds in the book’s pages). Silva’s beautiful photography does, however, manage to capture the persistent design formula of club spaces: they are ambitiously lit, hermetically closed, repurposed interiors. There is in fact a melancholic note that plays throughout the book and its contributors’ essays that discuss the longer history of Italian night architecture: a multigenerational nostalgia for an era of social and cultural innovation and the painful realization that its material history has left no traces. In many cases not even photographic evidence.

Under the auspices of the club reside populations that no one builds monuments to, that aren’t deemed worthy of a permanent physical presence in the city.

If clubs remain transient, traveling through arbitrarily available interiors, we can rest assured club culture and the populations that find refuge in their safe spaces won’t leave behind any trace in the material record of the city, no ruins of their own. And there’s no reason why they shouldn’t.

How might architects relate to this? Differently than they might think. A critical subset of architects make fools of themselves when confusing space for “space.” That is, space as in physical, measurable space, the chief content of architecture, compared to “space” as in metaphorical space — the space established by an idea. The architect’s fallacy is that the latter can be manipulated and designed using his/her standard repertoire of tools, as if it somehow would share the fundamental attributes of the former.

A substantial amount of architects’ attention towards club space/“space” has fallen under the category mistake described above, in the form of an architectural relational aesthetics obsessed with staging short-lived events or “situations” (this also includes many of the widely revered nightclub experiments of the so-called Radical Architecture generation in 1960s Florence, to which many of Nightswimming’s contributors both refer and belong).

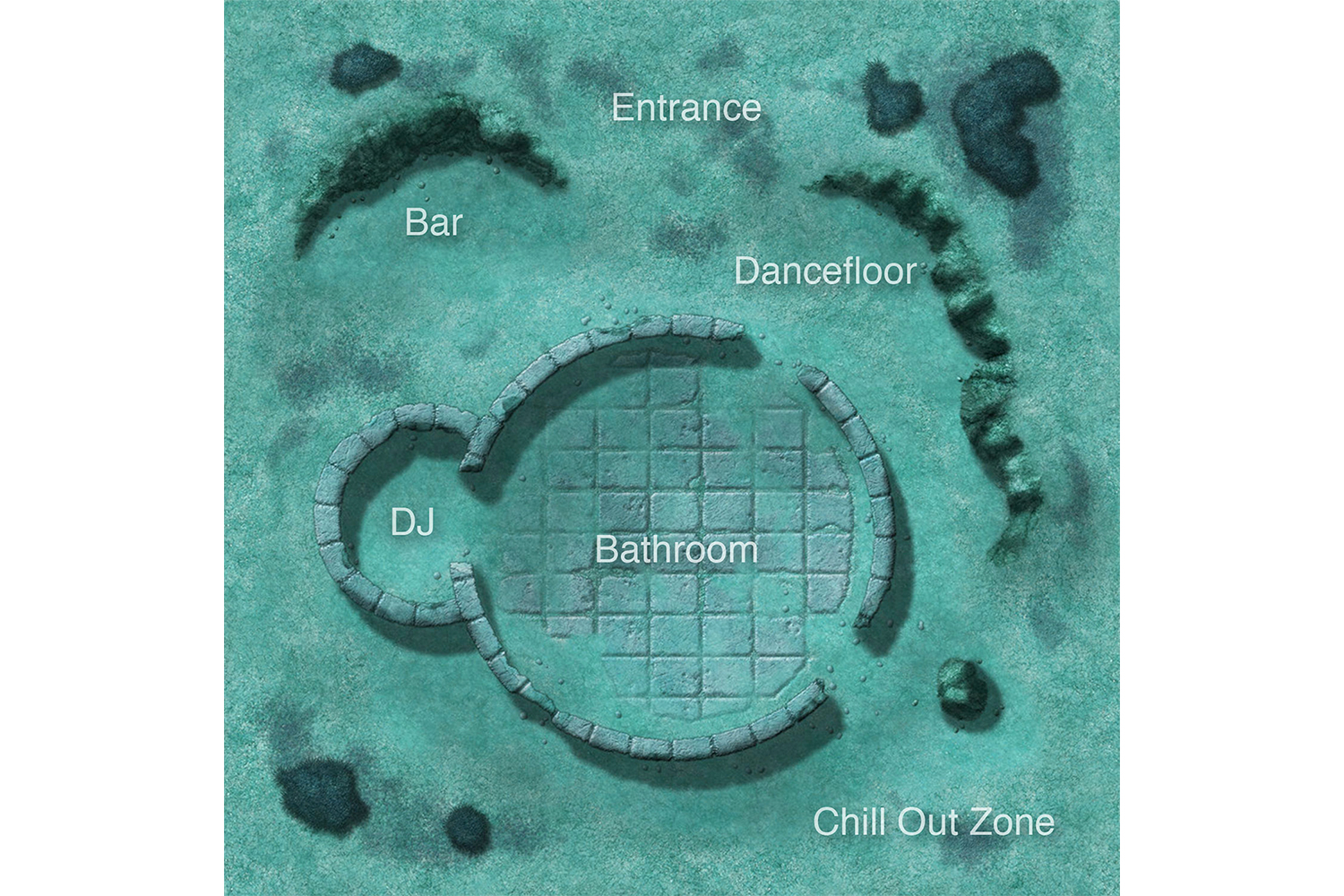

But clubs know how to program themselves. A much more effective contribution would be to vest clubs with the same level of architectural ambition as other building typologies that might have been historically more venerated (for example, the theater or the church): to consider them as actual spaces to be designed and constructed beyond the limitations of mere interior decoration. As a matter of fact, clubs are one of the very few types of architecture, besides maybe public bathhouses, which are so intimately involved with the staging and directing of human bodies interacting — sight, sound, smell, intimacy, inclusion and exclusion. And maybe these qualities, when embodied in architecture at a great enough resolution, could also reconcile the incommensurate timescales of a building that might last several centuries and an individual club that lasts less than a decade.

Secondly, architecture can rarely escape the condition of being property. “Millennials” — who constitute the majority of the current club generation — are purportedly “killing owning” and prefer access or rental rather than ownership of property. Essentially, this widely repeated claim is a euphemism for the economic disparity between millennials and earlier generations better situated on the property ladder. Not being able to afford to own is often a simple economic reality. Even if it is often prohibitively difficult to devise strategies to gain, and sustain, ownership of the spaces that our institutions inhabit, is the most effective way to battle, or better, influence, the tide of gentrification.

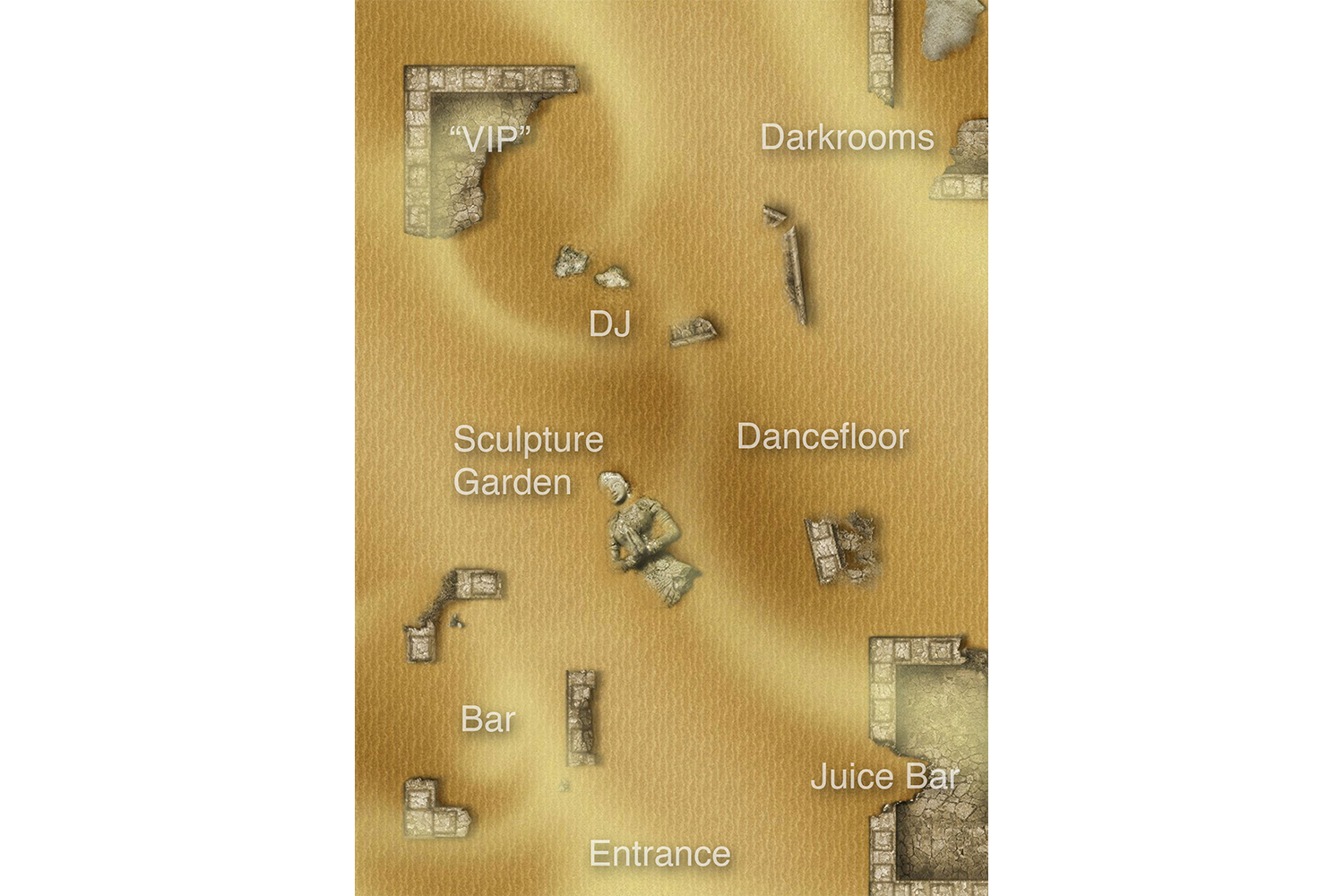

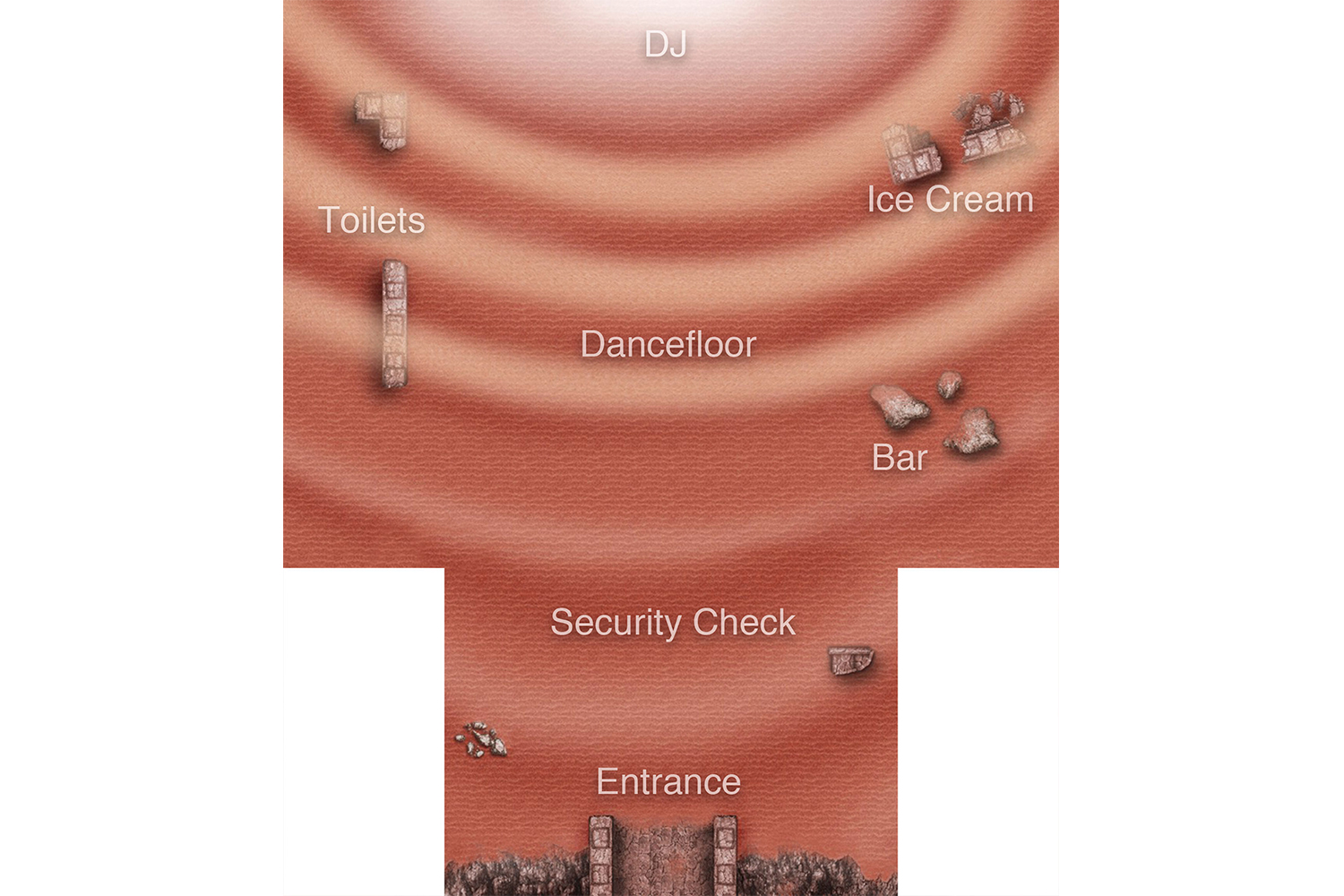

In short, we ought to try to conceive of clubs as buildings, as opposed to ephemeral interiors. We should think of clubs as strange/queer/monolithic/opaque/uglycute/temple-like buildings owned and operated by those who have the most at stake.

Finally, buildings might also matter in a sentimental register, as a physical record of the history of the city. In an era distinguished by social media, in which any occasion, space and interaction can be (and is) documented and instantly disseminated as image, video and sound, many of the most important clubs have chosen to police their digital boundaries in addition to their physical ones to fortify their “safeness”: photography inside isn’t allowed, to the degree that visitors’ social media accounts are afterwards scraped clean of any leaked recordings.

Though it may be under very different technological conditions, we are in a similar situation as the fleeting energy of 1960s Florentine nightlife: facing the prospect of a future with scarce evidence of a specific, historical club era. But perhaps this doesn’t matter if we have the potential of leaving beautiful ruins instead: ruins that testify across time that something worth the energy of piling up a building’s worth of material happened here.

It will be sad if the only future façade that club culture has is Berghain’s, courtesy of a GDR civil-servant architect. Even if no one can question its potential Ruinenwert.