In a poem from the 1970s, Martin Wong, in his angled scrawl, urges a “poisoned garden,” a “temple of dawn,” to “weave me in your sullen beauty, lose me in your smoke-ringed visions.” At this point teetering on the edge of committing to being a full-time artist, could he have known that these smoke-ringed visions might be his own? While he never stopped writing poetry, Wong would eventually move at the end of the 1970s from working in agitprop theater troupes in and around San Francisco, designing, in his friend and colleague Bambi Lake’s words, “heavily glittered” sets, to New York to dedicate himself to painting a symbolic language of signs and myths that would come to mirror the sullen beauty he longed for.

Through his eyes, his world becomes chunky, curved, squat. Once approached on the New York subway by a deaf person with a sign language brochure, Wong incorporated this language of hands — an expression akin to painting — into his canvases. His hands, made bulbous and rectangular, resemble Chinese stone carvings in their exaggeration. There is a touch of Philip Guston in his commitment to cartoonishly and self-knowingly illustrating his surroundings, yet Wong’s artist’s studio, in My Secret World 1978–81 (1984), is a hotel room along the South Street Seaport. The hotel’s red-brick facade gives way through windows to a sparsely furnished room, with a stack of books whose titles include Picture Book of Freaks and How to Make Money, and walls adorned with more paintings of Magic 8 Balls and red-brick facades — some of which are on show adjacently at Camden.These bricked-up visions abound in Wong’s paintings.

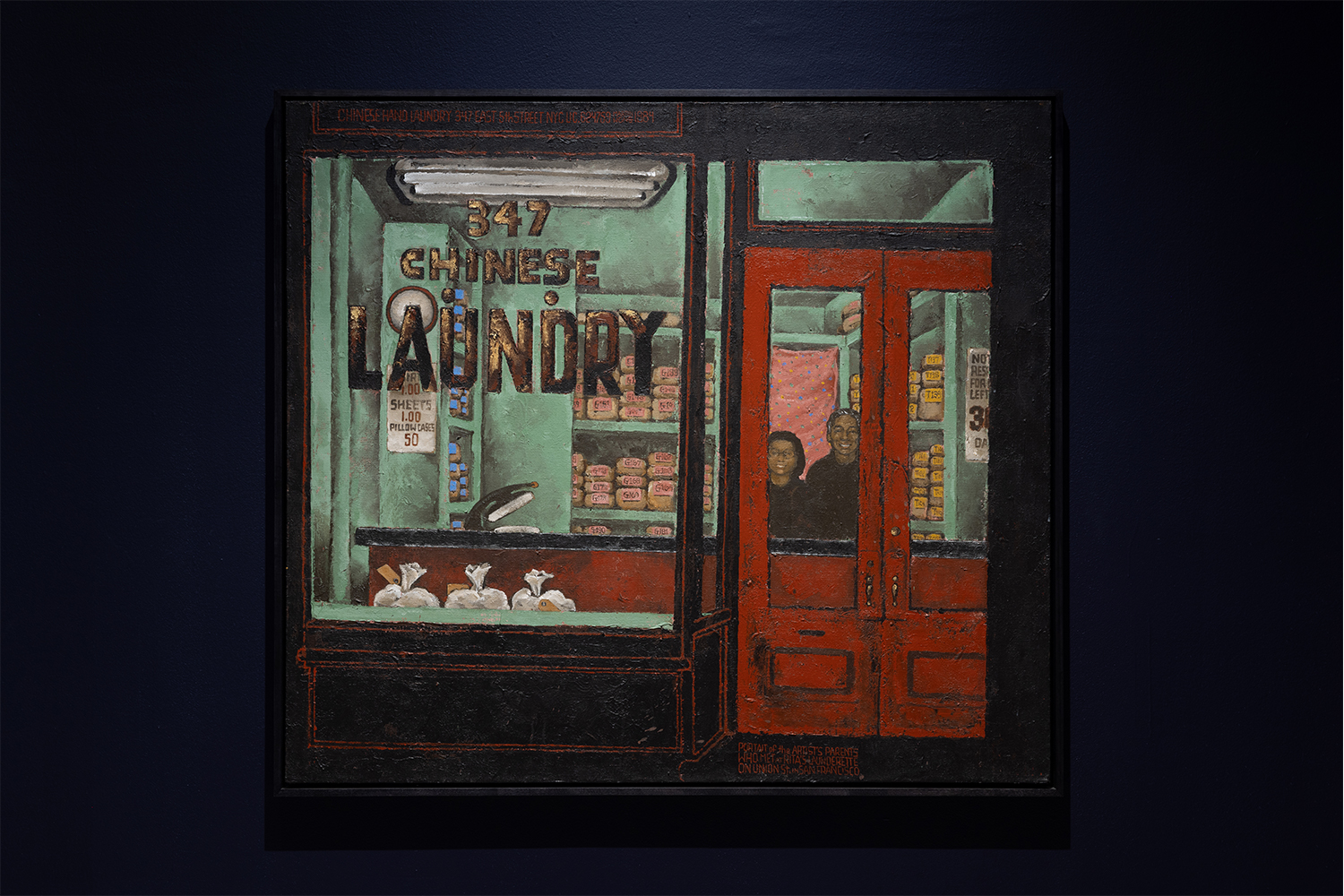

The deft impasto detail of each brick and its surrounding mortar, every one uniquely mottled, creates a flatness between foreground and background so that everything sits stubby and stubborn at the fore. The effect feels urgent in its graphic expression, the city rushing up to meet you rather than being depicted at a remove. Through his decades in New York, Wong was increasingly on the street: befriending artists, poets, workers, firefighters, criminals, drug addicts, many from the large Puerto Rican community he lived among in the Lower East Side. His earlier interest in set design is evident in his consciousness of architecture’s effect on how people live and move through the city. His burnt-out, decaying New York is not just a backdrop, but a character, a subject — a live spectacle of the gentrification Wong had witnessed on the West Coast and was continuing here. A sketchbook from the 1980s encloses the city skyline inside a Magic 8 Ball, like a Christmas snowglobe for wish-making. Adjacent in the vitrine is his Lower East Side Poem, a node to the “concrete tomb” his chosen home was becoming, what he calls “Rockefeller’s ghettocide,” as whole blocks of buildings were left derelict, razed, or burned down, to be eventually rebuilt as new. A suite of paintings from Wong’s 1986 exhibition at the Semaphore Gallery, titled “The Last Picture Show,” depicts a row of closed shop fronts and shuttered facades along Avenue B.

This chronological exhibition, touring throughout Europe and for many the first real introduction to the artist’s work, transitions from the improvisational joy and movement of the theater years to the heavy stasis of prison scenes drawn from stories told by his incarcerated friends. Locked doors and barriers narrate Wong’s mourning for the city itself, but also the city as container and catalyst for friendship, sex, love, artistry. In 1994, Wong was diagnosed with AIDS, like so many others in his urban community. He returned to San Francisco to his parents’ home, and increasingly dedicated his paintings to Chinatown and the pop-cultural symbols of his Chinese American identity. The last painting he completed — on the day he died in August 1999 — is included here, a cobalt-blue Patty Hearst as Kali, the Hindu goddess of death and time. In gold paint above her, Wong asks the question, “Did I ever have a chance?” This overdue cementing of his legacy makes it impossible not to reply “yes.”