“If place is always retrospective, how do we begin? With blatant flaws.”1

– Lisa Robertson

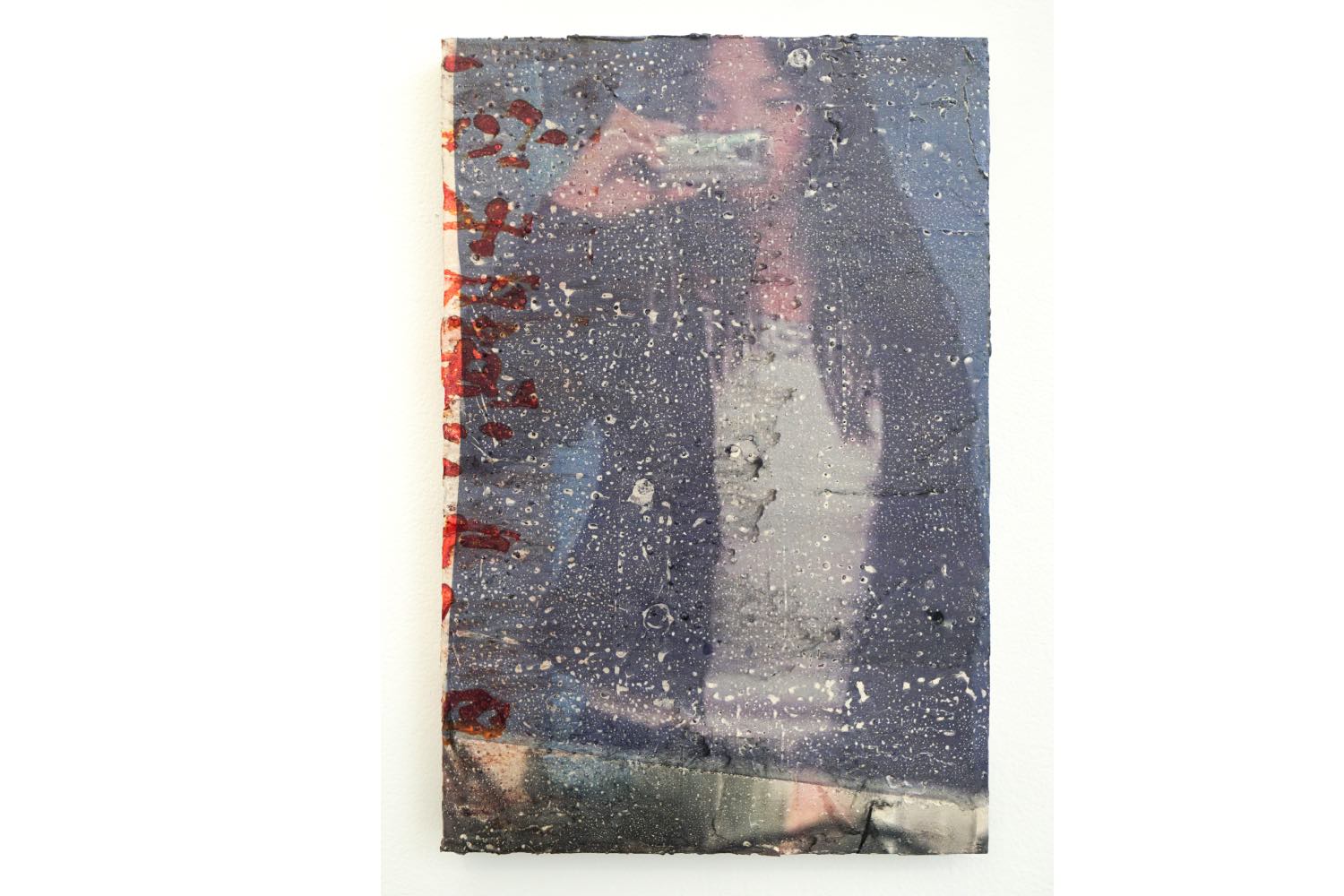

Lyric Shen’s oeuvre seems to be held between the flows of coagulation and dissolution. Typically, this in-between state materializes in her practice in the form of her sculpture-image combines, in which prints are transposed via wet transfer onto stoneware or ceramic. In these works, her images briefly take on a crystalline, physical form — only to then dissolve into decomposition and abstraction. Diminutive in size, these objects are marked by an almost trompe l’oeil quality. They appear at first to the viewer as prints on canvas, their illusory quality rendered all the more convincing by images that wrap around the porcelain “canvas” hiding where the material would betray itself, as well as by the presence of textured dots that evoke the toothed weave of canvas. In instances where the porcelain is laid bare — such as in Daxue (2025) and Paradise (2022) — the ceramic still reads as canvas (albeit seemingly thickly laden with gesso) in a way akin to Antoni Tàpies’s work from the 1950s, in which his incorporation of marble dust and sand made the supports for his paintings appear less as canvas and more as wall.

The photographs, pulled from familial archives and her own personal stash,resist any clear sense of signification, any singular sense of “aboutness.” During a studio visit, the artist explained that she chooses images primarily for their formal qualities — how they interact with her material process — rather than for any symbolic weight they may hold. Considering Shen’s use of wet transfer and her destabilization of the image at the level of signification, we can approach her work as being in conversation with (but diametrically opposed to) the likes of Robert Rauschenberg. In his case, he utilized the wet-transfer process to collage a polyphony of images onto a given surface in order to destabilize the meaning laden in those images. In Shen’s case, she wet-transfers a singular image, and mobilizes close-cropping and degradation to unsteady its meaning. In the close crop, the environmental clues that enable the reading of an image are cleaved off, leaving only the subject of the image in its most reduced or primordial state, a sort of ur-image. But these ur-images are quotidian in nature. Here, we are not left with symbolic archetypes for love, war, nature, etc., but rather mere “types” — a body, a room, an entrance.

When I spoke with Shen, she explained her interest in photographs that embody an uncanny quality or a certain type of “impossible” recognizability. For instance, the artist remarked that several people claimed to recognize the skewed and cropped photograph of the Guanyin statue at Taipei’s Longshan Temple in her Taihoku guanyin (2025), this being an impossibility considering these viewers had neither been to Taipei nor were versed in Buddhist statuary esoterica. In my own case, while in the artist’s studio, I had mistaken a work in progress bearing the transfer of a selfie by Shen for a still of Shu Qin from Millennium Mambo (2001). In this case, the mistake was due less to a compositional editing of the image (the crop) but rather a material edit (the breakdown) that obfuscated the image’s legibility. At the level of process, Shen prints on PVA film, which is then transferred onto the ceramic support in a water bath. The operation takes a mere eight to ten seconds, as the film begins to quickly deteriorate. Here, the window in which the image is legible or independent is fleeting. After the transfer is complete, the breakdown of the film abstracts the original content so it no longer remains a “pure” image, but one that is collapsed and inextricable from its support. By extension, the presence of cracks, bumps, and inconsistencies in the ceramic support underscores not only the image in its relationship to the material but, in particular, its surface. In a conversation with Devan Díaz about her use of clay, Shen argues that material possesses memory in “the same way that bodies have memories, sensitivities, and varied surfaces — like freckles, texture, skin, hair, all these things.”2 What becomes compelling here is that if we are to treat the image as a semiotic device, a cousin to language, what Shen’s attentiveness to surface and material does is draw attention to the physical or material vessel that undergirds the idealism of communication. Here, the image does not stand alone as such, but is inextricable from that which carries it.

While Shen’s ceramic works address surface, fragmentation, and materiality on an intimate scale, her more recent large-scale installation work translates these themes into spatial and architectural terms. Installed at Silke Lindner in New York earlier this year, Shen’s There is an occlusion (2025) marks both a break and a compelling development in the artist’s practice. This shift has occurred at the level of form and material, but functions to articulate several of the artist’s conceptual concerns with poignant clarity. Here, the artist constructed an imagined reproduction of a room where her mother and several of her family members lived in Yilan during the 1960s under martial law imposed by the Kuomintang government. Evoking the Japanese architecture of the original structure — an artifact of Taiwan’s occupation by Imperial Japan — There is an occlusion is a chimaera, simultaneously anachronistic and historically true to material. Kozo (mulberry) has been processed into a form of washi paper (traditionally used in Japanese sliding doors, among other architectural elements), but rather than forming a wall or entrance, it has become the basis for the roof, whose off-white, membrane-like surface allows for the partial penetration of light.

The rest of the room is constructed out of a mix of found wood, saggar clay, Chinese mesona (the key component of grass jelly), sand, hair, and Taiwanese cypress. Empty, barring the presence of three of Shen’s porcelain works, the sculpture is marked by a dream logic, akin to reality but not quite. Indeed, the psychologically charged quality of the work indicates Shen’s translation of the interiority of experience and memory into its outward and materialized form. On the one hand, there is no concrete model or referent for the building, only oral descriptions and drawings from the artist’s mother. On the other hand, this room (despite only ever experiencing it via description) is the site of a recurring nightmare in which the artist and her mother experience a home intrusion in a room with windows made of paper.

The quotation of the home to grapple with memory and psychic processes has been a repeated motif throughout contemporary sculptural practice. Gaston Bachelard, writing on the relationship between the home and memory in The Poetics of Space (1958), stated: “Memories are motionless, and the more securely they are fixed in space, the sounder they are.”3 Shen’s iteration, which oscillates between the solid and the provisional, the opaque and the translucent, comes across as a dialectical negotiation between Rachel Whiteread’s House (1993) and Do Ho Suh’s ephemeral textile-structures, particularly the quasi-placeless amalgam, Home Within Home Within Home Within Home Within Home (2013). In Whiteread’s work, she engaged processes of memorialization by casting an abandoned Victorian townhouse in cement, thus perpetuating its site-specificity while denying us the possibility of reinhabiting the house — a form of remembering hinged on total solidification. For Suh, his ghost-like edifices, formed out of permeable textile membranes, are inextricable from the artist’s memories, yet their form, which connotes a kind of transportability, draws out a kind of siteless-ness. Their penetrability (both ocular and spatial) as well as their monochromatic surface, which calls to mind a video game model that has not been fully rendered, provides the viewer an almost neutral surface on which to project memory or experience. Situated between the memorializing solidity of Whiteread and the ephemeral, memory-laden spaces of Suh, Shen’s structure inhabits a midpoint — an uncanny zone where specificity and vagueness cohabit. Here, the specific serves as a seed, germinating a simulacrum without a “true” basis, the sculpture acting as a virtual model of a possible structure or one in the midst of becoming, a mirror to the problem of processing memory. The sculpture’s austere façade allows for a degree of projectability on the part of the viewer without taking up the near-total mappability of Suh’s work. On the other hand, seemingly ad hoc construction suggests mobility without the site-specificity of Whiteread or the fluid transportability of Suh. What Shen’s house proposes, instead, is a meeting point between the subjectivity of the artist (which is never fully penetrable) and the subjectivity of the viewer who brings to this home their own (inaccessible) baggage, poetically evoking Hans-Georg Gadamer’s words in Truth and Method (1960): “Since we meet the artwork in the world and encounter a world in the individual artwork, the work of art is not some alien universe into which we are magically transported for a time. Rather, we learn to understand ourselves in and through it, and this means that we sublate the discontinuity and atomism of isolated experiences in the continuity of our own existence.”4

There is an occlusion contains an undoubtedly anthropomorphic quality. The façade takes up a skin-like quality in its translucency, an effect underscored by bio-organic material forming its basis as well as the literal presence of human hair. A textured surface, imperfect and marked. The anthropomorphization of the art object via engagement with the surface places Shen’s work in dialogue with the likes of Eva Hesse, Mia Westerlund Roosen, and in particular, Heidi Bucher’s “skinned” latex structures that draw a direct correlation between the body and the home. What I think occurs within Shen’s work is not a fixation on a given surface — painterly, bodily, or architectural — but an interrogation of it as a kind of general category. Even when a particular surface is evoked, it becomes inextricable from a larger cosmos of surfaces. Within her porcelain works, in which the surface is already highlighted via the medium’s qualities, the threshold between exterior and interior is emphasized by a repeated motif of depicting various structural membranes: facades in the case of Balcony in Zhonghe (2023); windows in the case of Promise’s Room (2023); and other transparent surfaces in Daxue (2025). Shen, herself a tattoo artist, spoke about a tattooed Jōmon-period figure in an interview with Cult Classic, saying, “Clay, the material, has such a memory of its own. That’s why clay bodies look so different, because of where they are extracted from, and the types of minerals and chemicals that are in each clay are so specific to where they’re from. So they interact with form and surface in really specific ways and carry a lot of information, data, and wisdom without the use of language or numbers. I feel like human bodies are similar in that way.”5 This engagement with clay – particularly porcelain — doubles down on the triangulation between types of surfaces, the medium itself bearing witness to a long history of equating porcelain with skin and the body.

What becomes articulated in Shen’s work is the way the surface, or the skin, being the barrier between inner and outer, acts as a carrier for extra-linguistic meaning but an imperfect one, primed for gaps, mistranslation, and projection. Following late Wittgensteinian logic, in which language as a system of communication already fails in cleanly transmitting meaning between subjects, Shen seems to lean into this feeling of ambiguity. By offering fragments of herself in her work while refusing total clarity (or attempting to position the art object as text), Shen highlights (via the surface) the art object as the grounds for an inter-subjective encounter that never attains a full-fledged illumination of either the viewer or the artist. Here is engagement with skin as poetics, as an architecture, as a vector of sensory impression that denies the mythology of depth. To return to Lisa Robertson: “We are aligned with a surface. We exchange mineral components with an historical territory, less like cyborgs than like speaking, ambulatory dirt.”