Eleanor Antin’s Blood of a Poet Box (1965–68) assembles, quite literally, the blood of a hundred poets: samples on glass microscope slides presented in a wooden box, accompanied by a list of donors that includes the artist’s husband, poet David Antin, beat poet Allen Ginsberg, and choreographer Yvonne Rainer. It is the earliest work in a long-overdue retrospective of the artist at Mudam, surprisingly her first in Europe. Blood of a Poet Box takes a historic reference literally: Jean Cocteau’s 1930 surrealist film Le Sang d’un poet, a visually stunning meditation on the calling and curse of being a poet, a storyteller.

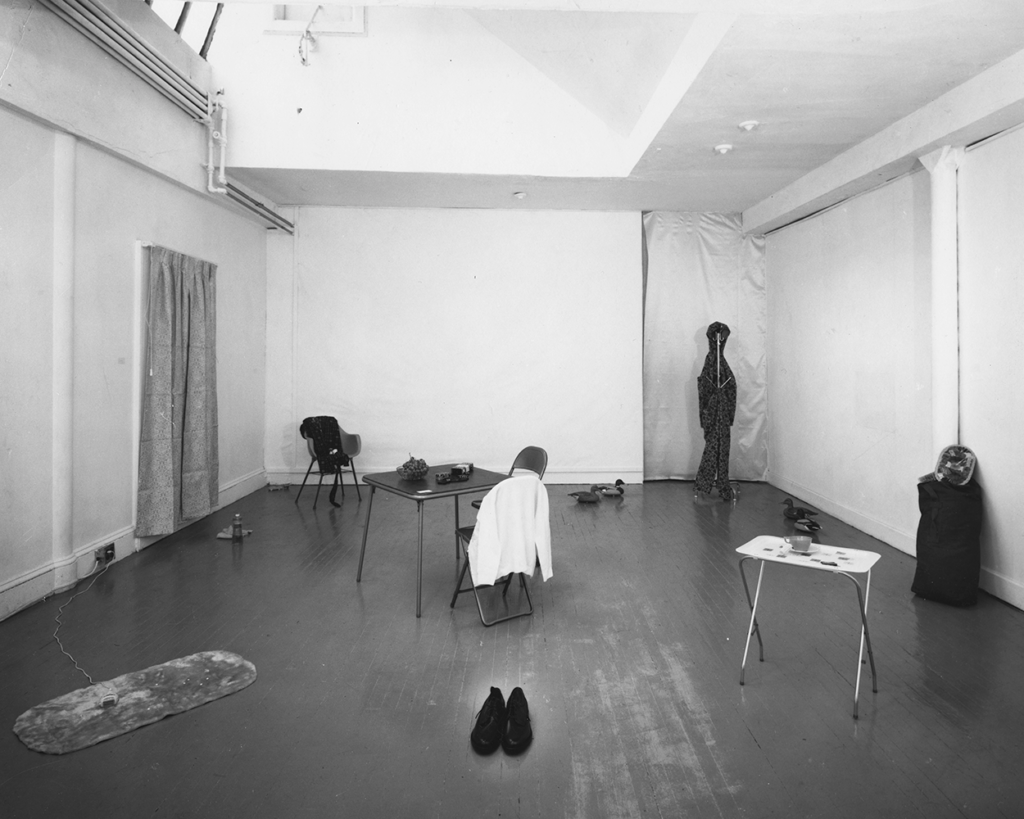

Unlike Cocteau’s cinematic exploration, Antin’s collection offers no poetry, revealing very little of the poets (other than their willingness to make themselves available to the young artist and have their fingers pricked for her art). What it does show, however, is the cunning sense of humor the artist cultivated, and the way it draws widely held conceptions into question, of what art could be and what artists could do. In the 1970s, Antin herself enters the frame, using her body as a site of a feminist critique that pokes fun at conventions of art. In Carving: A Traditional Sculpture (1972), she documents the slow progress of a diet in photographs, while the video Representational Painting (1971) captures the meticulous ritual of applying make-up.

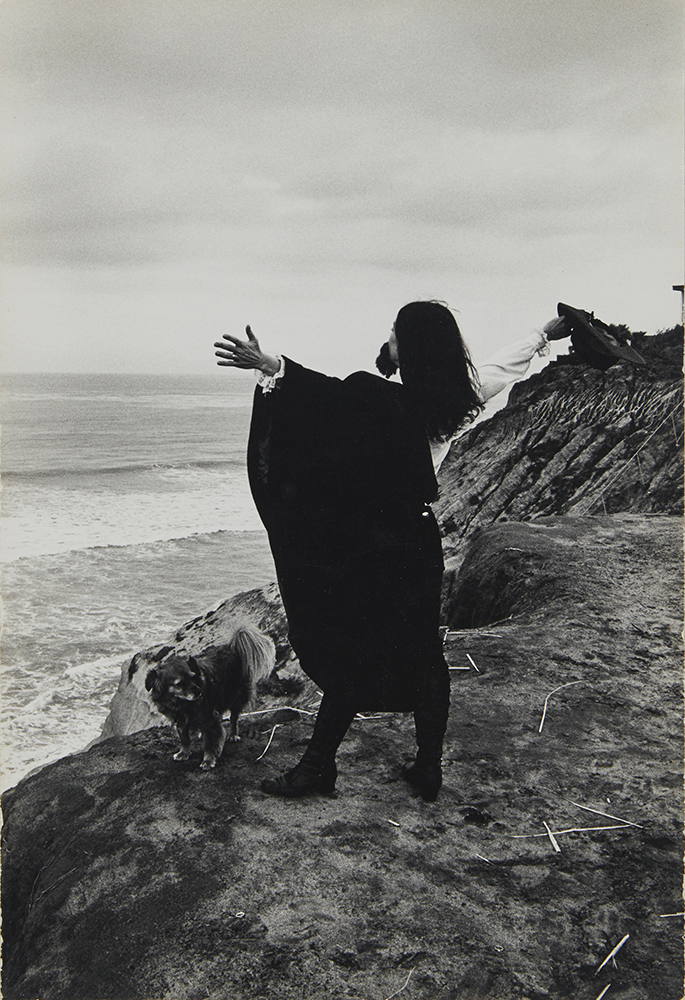

Both works resonate intensely today with the omnipresent imagery of (not only female) bodies in social media, such as in fitness or related posts. “I consider the usual aids to self-definition — sex, age, talent, time, and space — as tyrannical limitations upon my freedom of choice.” The daughter of a theatrical actress, Antin started developing increasingly intricate personas and alter egos across video, film, and photography, spanning genders, professions, and histories. In The King of Solana Beach (1974–75),she dons a beard and a costume to impersonate a benevolent royal, exiled from his own country, spending his time with his subjects in Southern California, casually sharing a beer with a group of youths on a park bench. As the artist put it in accompanying text: “Solana Beach is a small kingdom but a natural kingdom, for no kingdom should extend any further than its king can comfortably walk on any given day. My kingdom is the right size for my short legs.” Another has-been of sorts is the African American ballerina Eleonora Antinova, a former dancer with Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Through drawings and texts, including her memoir Recollections of My Life with Diaghilev 1919–1929 (1975–76), Antinova articulates the frustrations of being typecast in exoticized roles. In the “documentary-fiction” From the Archives of Modern Art (1987), Antinova appears in comedic shorts (and a “semi-blue movie”) that explore her decline into less ambitious artistic work, while Caught in the Act (1973) depicts the labor behind classical ballet poses, highlighting the constructed nature of both the male gaze and the female pose. The interplay of performer and photographer in the video shows the elaborate fabrication going into the creation of the perfect and ultimately fictitious image. Writing this, a thought forms: What in retrospect appears as a clearly constructed piece may not have been so from the get-go. There is also the aspect of retro-fabrication — because stories change as they are told and retold; they’re what turns data into information, like a commentary accompanying the news. Stories are the device that make sense of the world. This is where Antin’s continuing significance is most strongly felt, as her work expanded into feature films (The Last Night of Rasputin, 1989, The Man without a World, 1991), and writing (Conversations with Stalin, 2013).

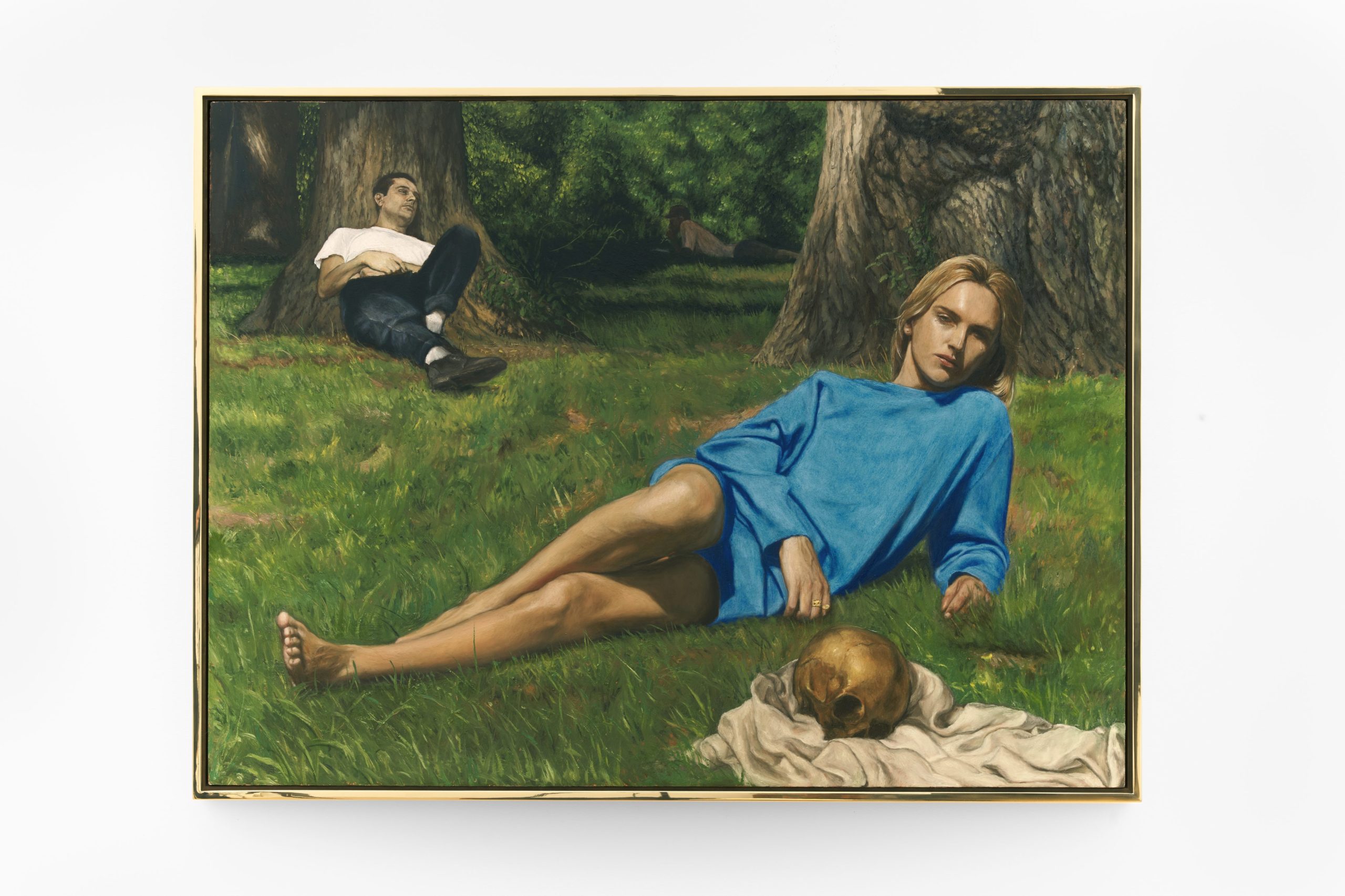

In the 2000s, her Historical Takes marked a return to photography and to San Diego. Unlike the modest urban landscapes of The King of Solana Beach, Antin stages opulent tableaux amid the sunlit hills of La Jolla, reimagining scenes from antiquity and mythological motifs with friends as models and elaborate costumes and props. In The Death of Petronius (2001), she renders the last moments of the author of The Satyricon, who, rather than give himself over to King Nero’s court, opened his veins, leaving behind his story of Rome succumbing to debauchery and decadence, a classic trope with an uncanny resemblance to present times.