Upon first encounter, the work of British-American artist Alexandra Metcalf captivates with its unapologetic femininity. Her paintings have a distinctly girlish palette — pastels, pinks, lilacs, yellows — which lend a sickly sweet edge that enthralls as much as it repels. Her subjects are mainly adolescent girls and women — or, more precisely, the process of their making and unmaking. And there is an indescribable emotional residue that seeps out of every work. Rachel Cusk observes that a “woman has special knowledge of process as the unifying characteristic of all that can be made: She understands it because she is subject to it, has experienced it as both curative and destructive, as health and disease, knows that its transformations are sometimes indistinguishable from deformities.”1 This sentence arrests with its profound truthfulness, and its intent reverberates throughout Metcalf’s work.

In her two-person exhibition with Scottish sculptor Karla Black at Capitain Petzel, Berlin, last year, Metcalf’s paintings and sculptures teemed with palpable anxiety. Strange landscapes and claustrophobic interiors were populated with motifs of full lips, ghostly figures, girls’ legs in patterned tights, and screaming floating heads. These paintings are not narrative-driven, but rather psychic spaces or embodiments of interiority. That obsessive sound of screaming (2024) — a creepy lurid pink landscape containing a floating mouth and a large black void — seemed to epitomize a state of female paralysis, trapped between expressing her feelings and being silenced. The overly emotional, dare we say, hysterical, woman is a centuries-old warning. “Compose yourself. Compose yourself. They are supposed to hold it in. To not act out. Dear, one must not create a scene,” writes Kate Zambreno in her book on the “mad-wives” of modernism, parroting the patriarchy. “The discipline and containment of diagnosis.”2

In The Rest Cure (2024), the descent to diagnosis is mythologized by Metcalf. Here, the ghost-like silhouette of a woman’s body lies in the foreground of an eerie, purple-bruised landscape. The body is either obscured or more likely being consumed by what appears to be a skeleton that is slowly decaying at the very forefront of the picture plane. The sky is atmospheric and full of images of the famous opera singer Maria Callas’s head. Replicated both as spectral white stencils and tiny black-and-white photographs decoupaged onto the painting, Callas is mostly shown mid-aria — the very aura of drama, or perhaps more directly, a symbol of a shrieking woman. As with much of Metcalf’s work, this painting is content rich, but its title is perhaps one of her most direct: the “rest cure” was a nineteenth-century treatment, invented by the neurologist Silas Weir Mitchell, for female hysteria and other nervous conditions. It involved prolonged bed rest in isolation from family and friends, being force fed a fat-rich diet (think milk and red meat), the denial of any real mental stimulation, and electrotherapy to activate idle muscles. Charlotte Perkins Gilman was prescribed this remedy, and later wrote the infamous short story “The Yellow Wallpaper” (1892) that sought to challenge the effectiveness of Mitchell’s therapy by recounting a woman’s psychotic breakdown resulting from rest cure. In Metcalf’s telling, if the figure of Callas is taken as emblematic of a woman at the break of psychosis, screaming into the void, then the lying figure shows us her diagnostic fate — a woman who has lost sight of herself, succumbing to the demise of her autonomy.

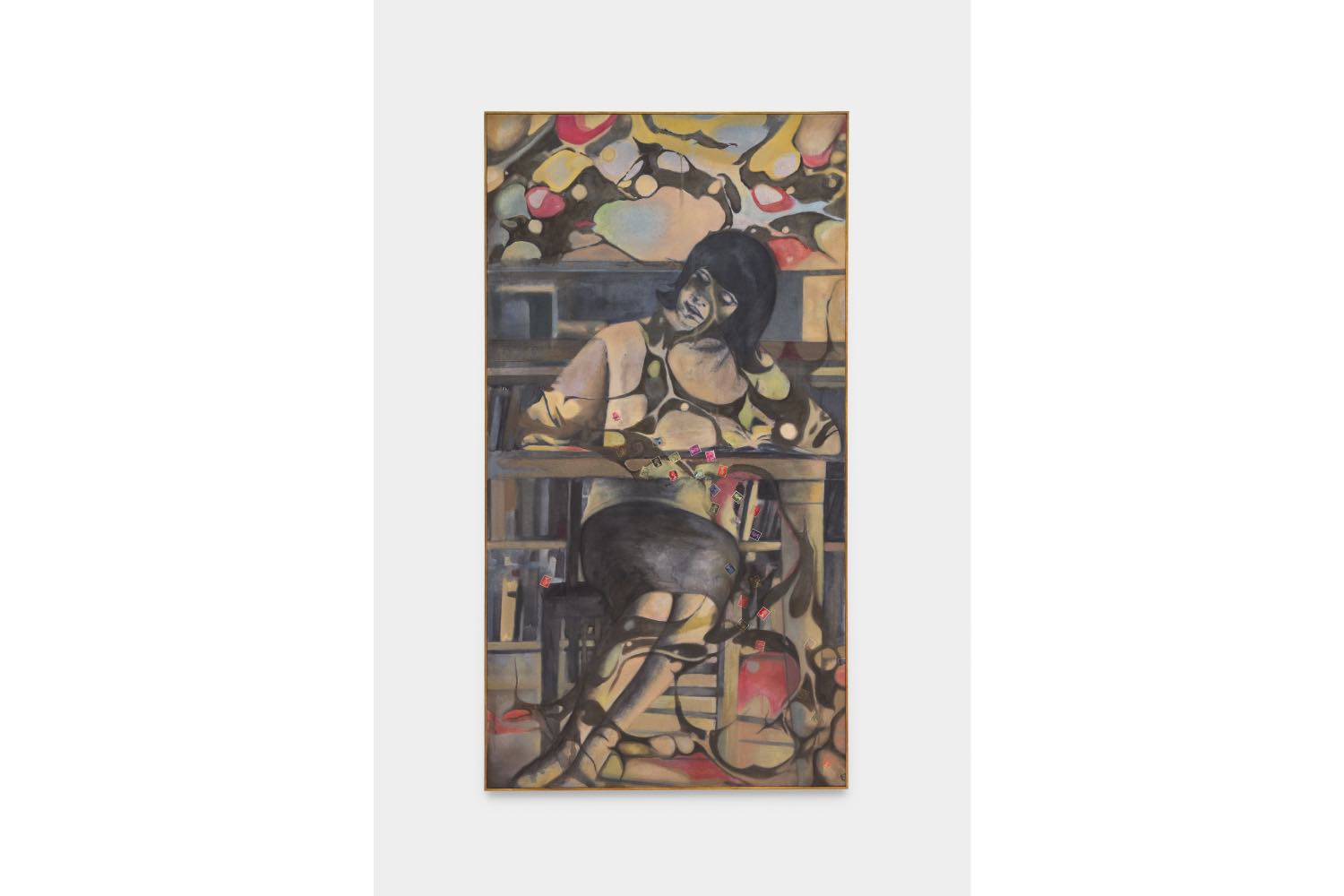

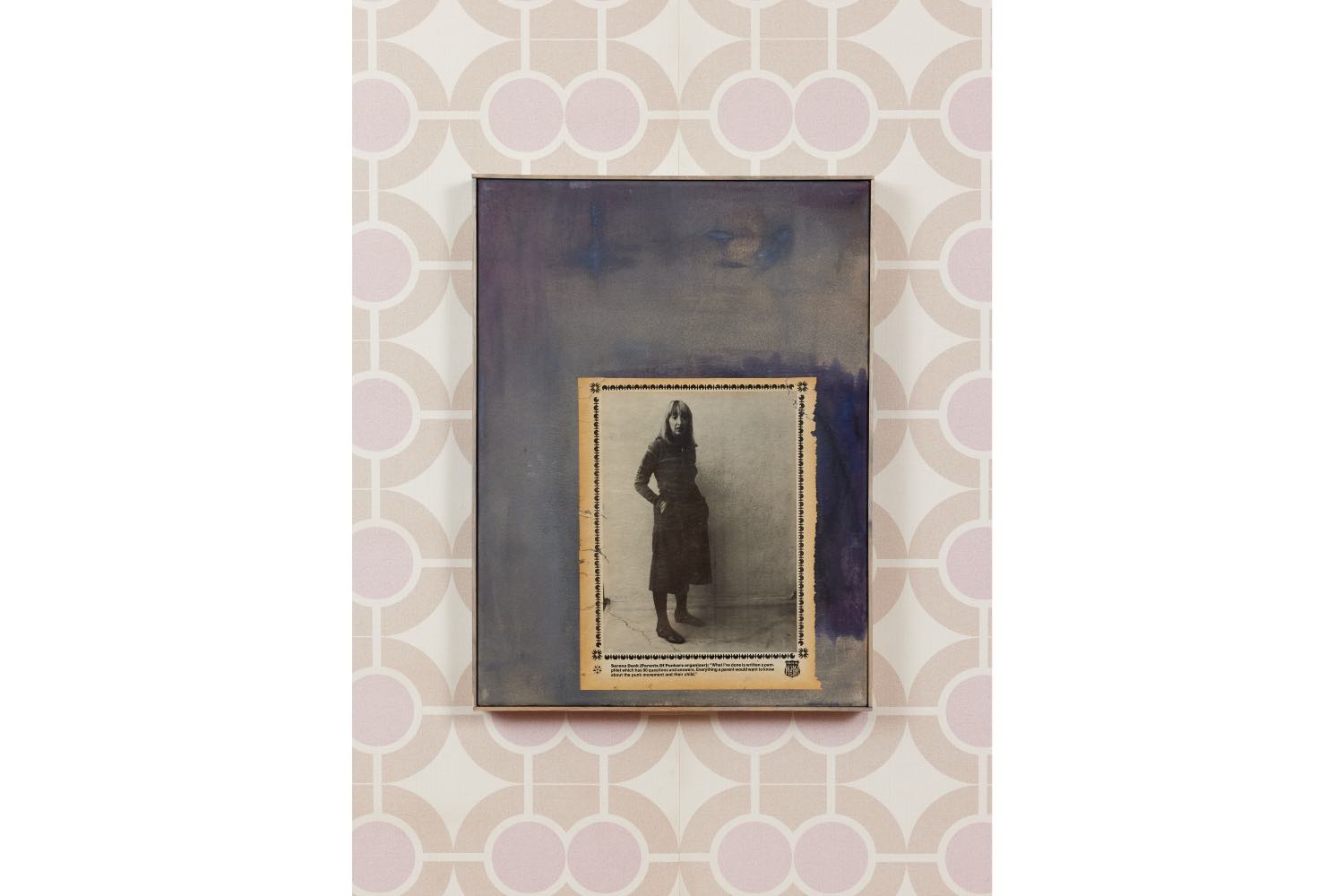

In “1st Edition,” her exhibition at Ginny on Frederick, London, in 2024, Metcalf folded in her previous explorations of madness with all the angst of a rebellious teenage girl coming of age and seeking her independence. Staged across time-periods — the Victorian Gothic, 1960s to ’70s counterculture, and today’s maladjusted teen crisis — the effect was a meditation on the notion of cyclical time, where progress is nonlinear and moral panic continually resurfaces. Densely patterned 1960s wallpaper covered the gallery, which spilled over into the paintings in different iterations. There, the figure of the adolescent girl is evoked through her clothing: from her striped socks to Harry Gordon’s popular “poster dresses” from the 1960s, she is trying to form a sense of self through layers upon layers of suffocating domesticity. The wallpaper in the paintings is torn and weeping, mining the same psychic terror of “The Yellow Wallpaper.”

In Silent Forms of Interspecies Panic (2024), Maria Callas’s disembodied head appears once more among the layers of clothing. As Metcalf’s recurrent personal trope for drama, Callas is both the anxious, emotional teenager and the despairing, panicked mother steeped in her patriarchal moral conditioning and containment. The theatrical centerpiece of the exhibition was The Mind is Maya (2024), an imposing wooden spiral staircase that ascended toward a dark hole in the ceiling. As with many of Metcalf’s sculptures, the staircase is anthropomorphic, transformed into the archetypal Gothic madwoman in the attic, spiraling out of control. It stood like a satirical klaxon — a loud, ironic signal of how the artist’s work straddles horror and humor. If everything seems a little over the top or unhinged, I think this was the point.

Through all of Metcalf’s fondness for theatricality and exaggerated malaise, there lies a more exacting exploration of the notions of care and containment. The uneasy, tormented territory she depicts illuminates how care exists on ambivalent ground upheld by uneven power dynamics and phallocentric ideas on linear progress.

Beyond the work’s content, there is a material seriousness found in the precision used in its making. The sculptures are meticulously handcrafted by the artist using materials and objects authentic to the time period she references, recalling the uncanny handmade sculptures of Robert Gober. The traditionally masculine skills of stained glass, handcrafted woodwork, or cast bronze that she has mastered are combined with the marks of feminine craft and decorative arts: small buttons that hint at the act of sewing (historically keeping women’s idle hands busy) are often inlaid into wood, for example. In Metcalf’s paintings, her predilection for decoupage is similarly pointed. These forms of gendered labor are deliberately elicited and undermined. In this sense, process and subject become enmeshed, or as Metcalf explains, “the process of making is part of the narrative.”

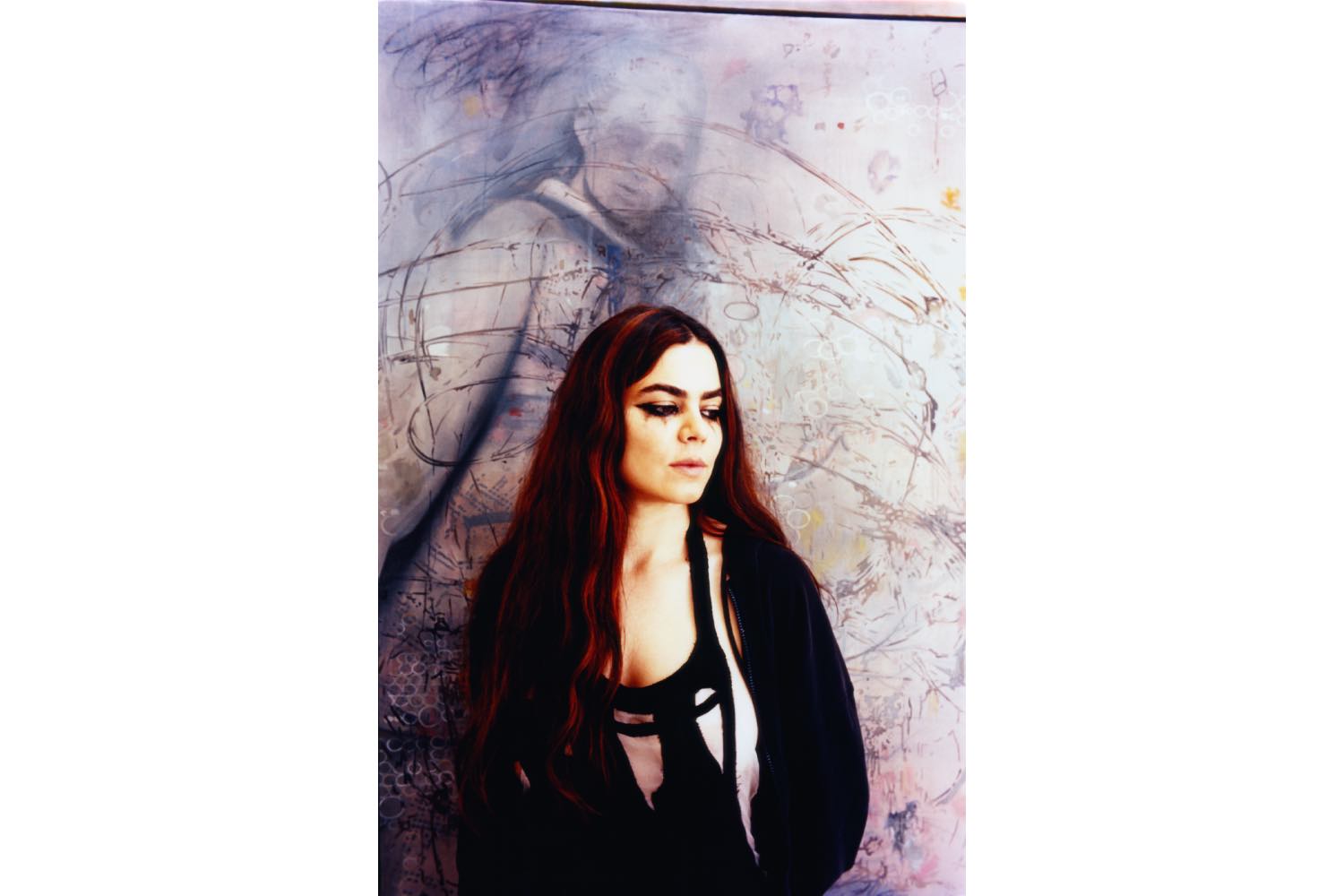

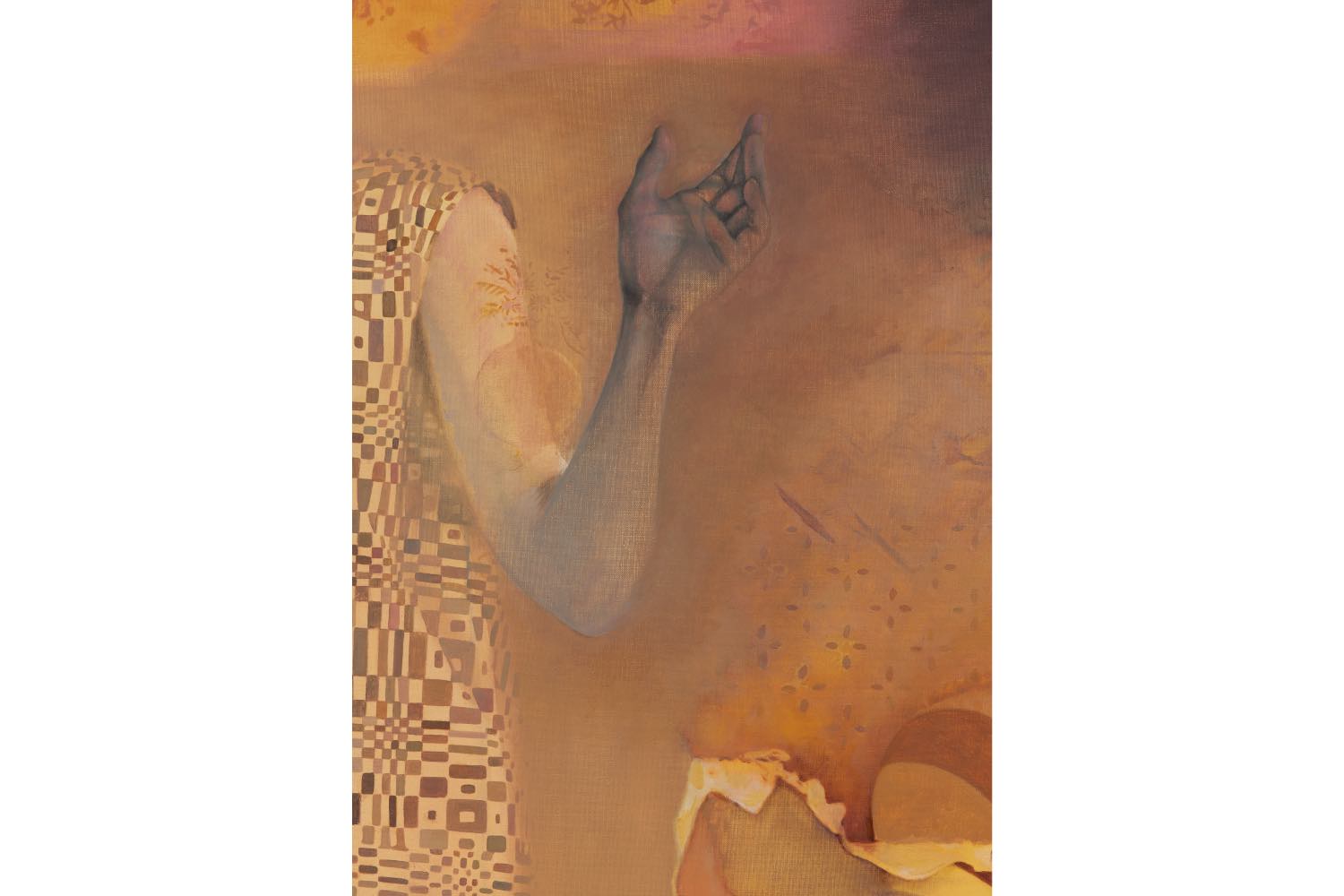

The paintings have a similar procedural proficiency. The figure-ground relationship in Metcalf’s paintings is frequently muddled as she creates layers of paint that appear transient. This allows her objects and figures to appear ghostlike — like memories that fade in and out of the mind’s eye — providing them with their particular etherealness. The use of sponges to rub and pull at the paint and the scratching into the surface with clay tools or a palette knife, alongside other techniques – frottage, decoupage, stenciling – all help her achieve this. Her command of color is particularly skilled, and she frequently uses the various tonalities of a single color across a picture in order to evoke a greater cosmic quality. In this sense, many of Metcalf’s paintings can be read as studies on the tones of her chosen palette. In The Etiquette of ….. (2025), for example, the color yellow is applied in hues from gold to a smudged green. The effect is that all details are caught between the surface and the background. The two girls (who form the work’s subject) are depicted as half-formed impressions — both there and not — suspended between emotional release and its suppression.

In her current exhibition, “Gaaaaaaasp,” at The Perimeter in London, Metcalf has created her own imagined version of London’s infamous asylum, Bedlam (Bethlam Hospital). There, the constant muffled threat of being pathologized is taken to the next level as care becomes fully institutionalized. There is a surgical theater (think procedures like lobotomies, craniectomies, and electroconvulsive therapy); a wallpapered waiting room where a television plays Cam 2017/2018 (2025), a silent black-and-white video diary of Metcalf’s own therapy sessions; and through the examination window, we see a field of canes with protruding pregnant bellies. The patients found in the theater are symbolized as mobile surgical lamps consistent with 1960s design, but here are replicated by the artist in vacuum-formed plastic, hand-dyed a copper color. The hospital beds are composed of found 1960s sun loungers that are attached to antique trunks used by the military in the 1880s to transport camp-beds. The decision to construct these “figures” in plastic emerged from Metcalf’s research into Lee Bontecou’s lesser-known, but nonetheless exceptional, 1960s plastic flower sculptures. The material is an apt choice, rendering them as ghosts — perhaps left behind after the mass deinstitutionalization that occurred in the 1960s, following the growth of the antipsychiatry movement. As with all of Metcalf’s work that disrupts temporal logics, histories of care collapse in on one another here. Her aesthetics may reflect the past, but they hold a mirror to the crisis in care and mental health that is currently unfolding: the post-COVID fallout for teenagers and young people, the damaging effects of social media and cyberbullying and the failing healthcare systems following years of austerity.

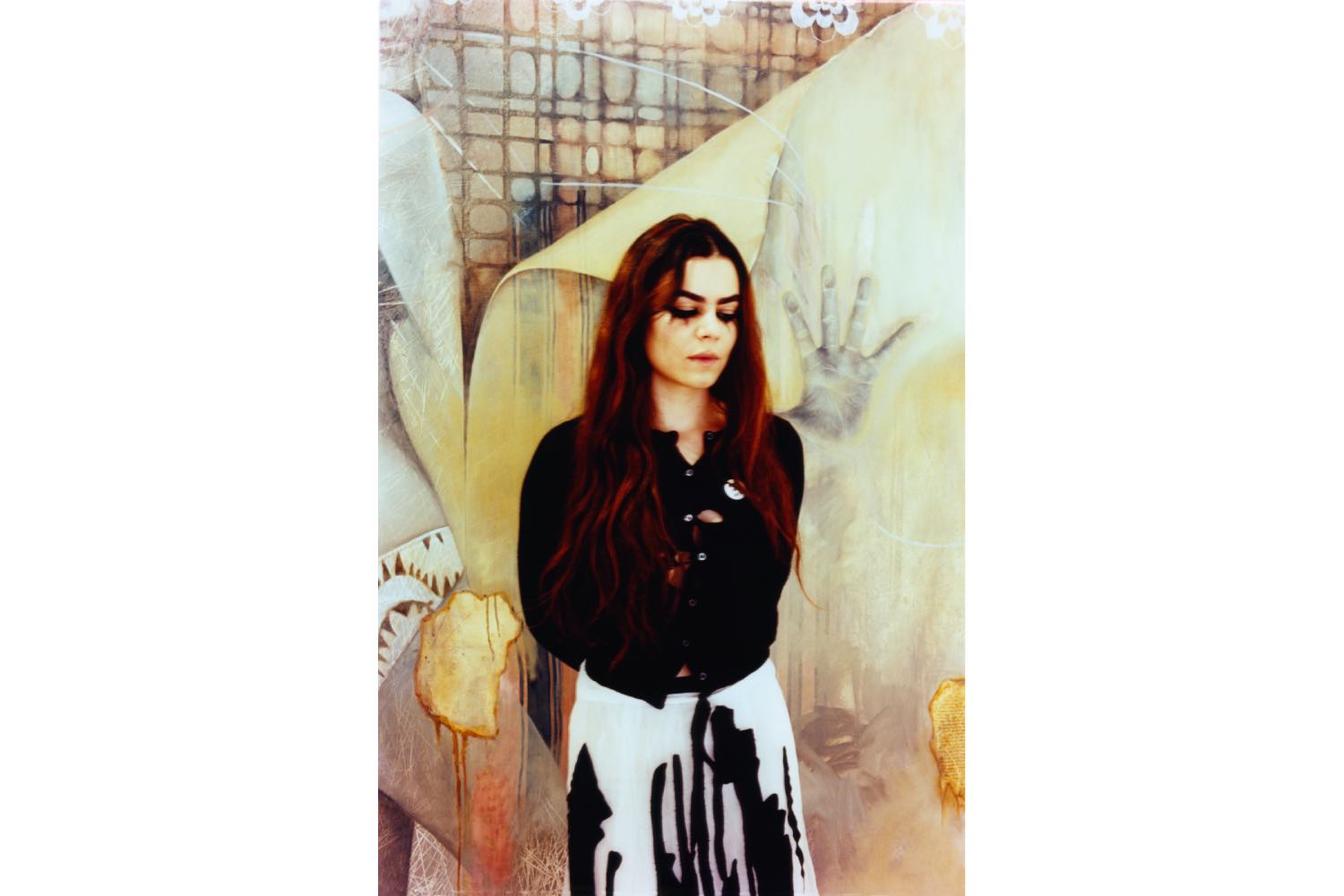

This exhibition also continues Metcalf’s exploration of confinement. If the domestic space was previously represented as stifling — clawing at one’s autonomy — the asylum is the epitome of subjugation. In both places, the only escape is in the mind that has been diagnosed as “sick.” The paintings across The Perimeter show — as if made by one of the patients — express the feeling of interior conflict. The imagery pushes and pulls –– girls smiling or whispering secrets contrast with scratches into the surface or a hand reaching outward in distress. “Compose yourself. Compose yourself. They are supposed to hold it in. To control themselves. Perhaps the fury is one’s own containment. If one wasn’t so contained, one wouldn’t be so furious,”3 Zambreno writes.

Throughout Metcalf’s universe, containment is rendered as a recurring ill — it is a horror story that will not go away. While nothing about her work is intended to appear as prescriptive, she poses a space where lessons from the past haunt the present. Through her repertoire of endless surfaces, excessive patterning, disquieting immersive installations, ghostly figures, and psychic spaces, she demonstrates how emotional spillage is inescapable and vulnerability is necessary.

The curator and art historian Catherine de Zegher, who has long championed an aesthetics of femininity, wrote in 2020: “We need more inclusive and empathic models of coexistence in a twenty-first-century society — a society that is tending to be increasingly manipulative, deceptive, intolerant, and violent.”4 In a time when everything seems to be spiraling backward — Trump’s America has reclaimed women’s bodily agency, the United Kingdom is reducing transwomen’s rights, and the manosphere is taking hold of a generation, teaching them that masculinity and all its inherent emotional restraint is the answer to reclaiming supposed lost dominance — what Metcalf’s work appears to show us is that persisting in a politics based on “the discipline and containment of diagnosis” seems to be the exact opposite of what is needed.