How to jump on the information superhighway bandwagon? The past couple of years have seen dozens of exhibitions dealing with networked technology and its effects. A list would be boring and is sure to expire within six months, but such “networked exhibitions” have been held in institutions ranging from Tate Modern in London to the Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, from the Serralves Foundation in Portugal to the Kunstpalais Erlangen in Germany. At the time of writing, London is at a high moment of digitally minded projects. There’s “Big Bang Data” at Somerset House, solo shows for tech-obsessed artist Simon Denny and digital painter Michael Craig-Martin at Serpentine Galleries, and Whitechapel Gallery’s massive “Electronic Superhighway,” a survey of the impact of computer and internet technologies on art from the mid-1960s, which opens on January 29 and is on view through May.

If it feels like a zeitgeist, it might be anxiety. Museums have engaged with networked technology for a long time — they have websites and maintain presence on different social-media platforms, they collect and display digital and net art, they introduce digital experiences into their galleries, they collaborate with Google Art Project. This surge of exhibitions, however, goes beyond the complicated relationship between museums and technology, and complicates it further by making technology into the subject on display. These are not net art exhibitions, nor are they interrogations into the effect technology has had on art. Rather, the goal of these shows is to examine the role of the digital in our society. It begs the question, Why now? And another: Why an exhibition?

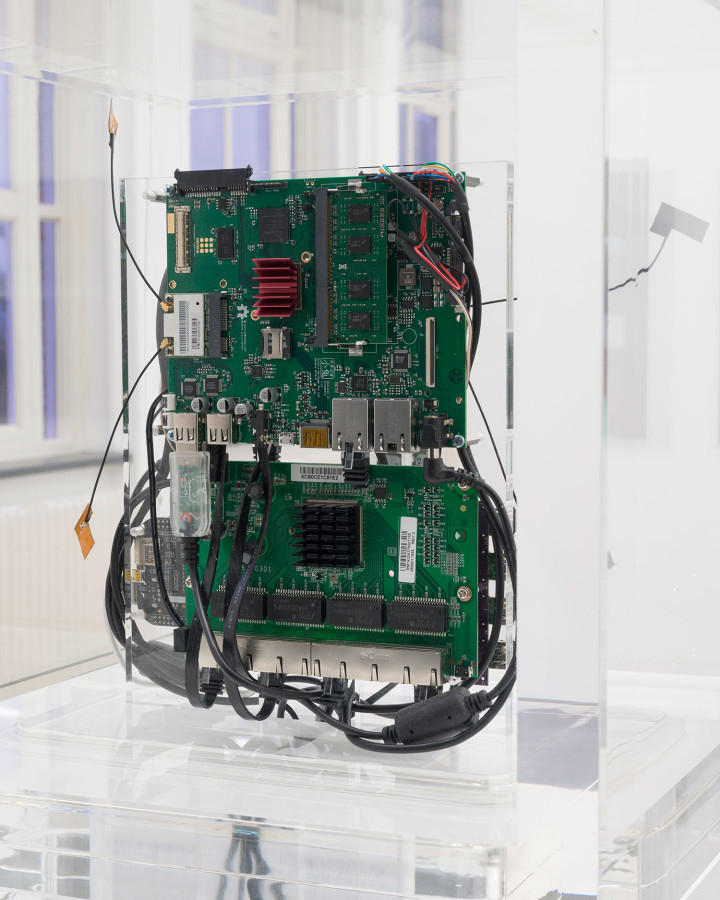

Beyond the déjà vu effect created by the fact that the artists (as well as the checklists) overlap in many occasions, the curatorial methodologies on view represent a catchall attempt to respond to the current intellectual climate while also appropriating it by emphasizing visibility as a technique to counter preconceived notions about technology and its role in our lives. At the Serralves Museum, in Porto, in June 2015, the exhibition “Under the Clouds: From Paranoia to the Digital Sublime” attempted to draw a direct line from the cloud of the atomic mushroom to cloud computing, calling attention to the way artists confront the changing interfaces that affect the way we live today. But the “cloud” in cloud computing is, as we now recognize, an abstraction. The cloud is just another computer (actually many other computers, high-capacity block storage, databases that monitor demand, and a huge amount of server space). Calling this mesh a “cloud” is, as the wall text in “Big Bang Data” reads, “one of the most deceptive metaphors ever coined,” since it’s a complex network requiring hefty amounts of hardware, space, and energy.

The didactic tone is included in the price of admission: even though the networked exhibition’s text routinely includes verbs like “reveal,” “hidden,” and many mentions of “online/offline,” “data,” and “network,” it is careful not to seem too conspiratorial, too techno-skeptic, too pessimistic. What amount of information do you presume a viewer has about current discourses around networked technology? What degree of wariness? Following Edward Snowden’s revelation of the NSA’s spying on both US and foreign citizens, it is no longer fashion-forward to be optimistic about the internet. Nor is it possible to ignore it. The exhibition communicates that, while also celebrating it, since a growing number of artists refer to these technologies in their work.

Not to dwell too much on sameness, the networked exhibitions provide us with a fascinating case study of changing attitudes toward the display of technology. At “Big Bang Data,” for example, there was one odd section in which a timeline of electronic storage devices from the past sixty years was on view, the objects shown on plinths, covered by semicircular plastic spheres (Did you ever look at a floppy disk and say, “this belongs in a museum”? Well, that day has officially arrived). Beyond showing the actual object of technology, there’s also the question of how to show its content in the gallery space. These exhibitions are full of iPads, computers, screens and simulations. Though most contemporary art exhibitions include digital aspects, from projections to touchscreens, certain tropes have emerged from the networked exhibition, including maps, data visualizations using live data from the web, and clocks. The richness of screen-based work marks a turn in approaches to new media art, from viewers complaining that they work in front of a computer all day, and do not want to see art on it in their free time, to a growing habit of consuming media — Netflix, YouTube — onscreen. What was always at stake in the presentation of new media was differing levels of familiarity with technology among the audience members. That is no longer the issue, but now approaches diverge in relation to the values and effect of these media. Especially when it comes to the internet. The didactic tension in these exhibitions between joining the conversation about technology and not wanting to seem too pessimistic is very evident in the relation to the audience: these exhibitions may display the video Laura Poitras and Glenn Greenwald shot of Edward Snowden in a Hong Kong hotel, included on the Guardian’s website alongside Greenwald’s first summation of the Snowden leaks. They include the voices of thinkers about civil liberties online and the work of artists who have voiced their concerns about the growingly corporate, growingly controlled space of the internet. All of which is almost ironic when you consider that the museums also encourage the viewers to post about (I mean, “discuss,” which equals “disseminate”) the exhibition on social networks using specific hashtags created for the show.

This is disconcerting because the networked exhibition charts conflicting tendencies toward the subject of networked technology and data. When tying art and technology, visibility emerges as a strategy to counter power structures that have emerged online. Language is a huge part of that — terms like “the cloud,” or even worse, “openness.” Open is good: it’s Google, Wikipedia, decentralization. It’s the shared resources of open-source technology (though open source is also a way of keeping free software business-friendly, constantly improved by way of the work of the multitude). Though “open” may stand for much good, it’s also a way of evading discussion of ownership and equity, highlighting the agency of the user but also disguising the responsibility of the corporation and the power imbalance between the single user and Google. And “open” is an easy example. It’s not the discussion of the internet as a “democratizing” tool, which has grown exponentially since the so called social-media revolutions of the Arab Spring, a discourse promoted by the same social-media platforms that benefit from their users’ free labor and eschewing of copyright, the same platforms that share information with governments from the US to China. This is the conceptual framework that underpins the way we think about technology: language is a tool meant to conceal, to abstract what is already vague. And the networks are purposefully vague. Though we’ve all seen images of server farms and know fiber optic cables run alongside most infrastructure, from highways to gas pipes, we think of the internet as intangible and omnipresent.

What is the role of art in countering this? Visualization is crucial. For example, submarine cable maps — one of which is shown at the entrance to “Big Bang Data” — expose the structures that lie at the heart of global trade and exchange and who has access to these (easy to guess which continent has the fewest connections). Another example: noting that all articles about the NSA were illustrated with the same image released by the NSA, artist Trevor Paglen took aerial photographs of the NSA headquarters in Maryland (a project assisted by Creative Time) and released them on public domain. One of these is art, the other isn’t. The networked exhibitions bring them together in a museum. This flattening of the but-is-it-art hierarchy is not what’s important here; it’s the idea — the belief — that the way to counter the invisible is by rendering it visible, and that this method should be put on display.

The creation of images is only one strategy, and as such it is a step, not a solution. Emphasizing it as more than that is at fault, not for assuming art can do more than it can, because calling attention is crucial, but for the reliance on image-making as an only, or central, strategy. Artists in the networked exhibitions suggest abstract solutions, as in Zach Blass’s masks that disguise you from face recognition software (Facial Weaponization Suite, 2011–ongoing); draw attention to the problems of the technologies we all use: Owen Mundy’s project I Know Where Your Cat Lives (2014) turns metadata into awareness by taking images of cats circulating on the internet and juxtaposing them with Google Maps by way of the latitude and longitude coordinates embedded in the image, exposing just how much privacy we concede when using services like Flickr; they bring up policy issues in both their visual work and their writing (Trevor Paglen, James Bridle). Part of the answer to the “why now?” question is that after the Snowden leaks, our disenchantment with the net optimism of the ’90s is evident. This larger socio-political discourse is referred to in the works of artists, which is why art institutions follow. The answer to “why now?” is thus evident in museums’ mission to historicize, present and conserve the art of the past and present, which means that the critical visual culture of the present moment belongs in the exhibition space.

What feels like a hot take may actually belong in the museum galleries. The temporary nature of exhibitions makes them suitable to discuss a constantly changing topic. And their nonpermanent state also separates them from the institution’s digital strategy. Museums have had a complex and interesting relationship with the data they generate. They use it to fundraise (as they always did from visitor surveys, only now they include information gathered on their websites and social-media profiles), but also for the creation of crowdsourced knowledge and content (consider the Brooklyn Museum’s tagging game, which was emulated widely, where visitors to the website were invited to tag the online collection; the same museum also had a crowd-curated exhibition, aptly titled “click” for its online selection process, back in 2008) and decisions about installation (by tracking visitors’ movement through the space and the online collection). All of this has been widely criticized as a preference for Silicon Valley logic over lessons learned over centuries of museum history, but it provides a small-scale reflection of the side effects of networked technology, namely the creation of data, and a lot of it. Data is the currency of the network; museums recognize that.

Still, we don’t need a way out of the internet (though some works, like Philipp Adrian’s #oneSecond, 2012, on view at “Big Bang Data,” imply that we do; #oneSecond is a set of four books recording the 5,522 tweets posted by people on November 9, 2012, at 14:47:36 GMT; Adrian tries to save these moments from disappearing in the timeline, as if we need to be saved from the pace of the network and the networked exhibition doesn’t advocate for one. The exhibition space is a place where a lot of cultural production beyond the showing of artworks takes place. And it may be a better location for these conversations to happen than the institution’s website or the conferences and panels it organizes. For that to be true, the curating of such exhibitions needs to be less timid and cautious, to include less art (and information) that tells, rather than shows, and to discuss other subjects that result from networked technology, namely policy issues, access, digital labor, and the financial structures that sustain these problems. Maybe that’ll be the second wave of networked exhibitions. (There may not be a second wave, though they say fashion recycles itself every twenty years. Labor, access and policy are sure to remain a problem.)

In a piece for the Guardian, Charlie Brooker, the creator of the popular Channel 4 television series about technology Black Mirror, defines the show’s setting as “the area between delight and discomfort” — the fascination with and admiration of technology, the reliance on it, and the fear of it as a system of a control. Arguably, that area is where we all reside. Arguably, this is also where contemporary art resides. We don’t want art that reaffirms our beliefs, that exemplifies what we already knew, that makes us feel comfortable and complicit. Beyond visualizing, beyond discourse, the discomfort might be the most important aspect these exhibitions press.