One cannot think of the contemporary grotesque without cuteness. Morally vacant, cuteness fuels the slot machines of internet scrolls, firing up synapses and optimizing attention spans for the longest time possible lulled in the comforting state of spectatorship. Agnieszka Polska is an artist who harbors this logic of audiovisual media that hooks us mindless – that is, she sets traps, in the same way that ASMR or TikTok are entrapping. In her trickery, Polska offers some ways out of our spectator stupor –– and perhaps enforces them, even if it is by the bleak means of a bait-and-switch that spiritually pulls the rug from underneath us. Unease is produced in her video works at every level of depth, from the simplest tools of editing, through whatever the characters tell us about their unsettling world to the philosophical trouble of what we’re left with in ours after exiting the loop. And ultimately, the state of our world is her underlying subject. Polska draws from philosophy, neuroscience, social history, cybernetics, and economy to secretly scaffold the structure for her storytelling, fable-like,in a parallel to how, after all, fables were originally vehicles for knowledge. When confronting the existential dread and confusion of today’s reality, her focus inevitably lands on technology and the powers that guide its emotional relationship to us. Her most recently exhibited project, the film The Books of Flowers (2023), presented at the M HKA in Antwerp, uses AI-generated imagery to approach the techno-capitalist world order with a question – what if someone other than us became the most seductive storyteller?

Tosia Leniarska: What brings you to Australia and this particular community you’re staying with right now?

Agnieszka Polska: It is not any project of mine; I’m here for family reasons. I’m in Roebourne (Ieramugadu) in Western Australia, a small Aboriginal community of Yindjibarndi and Ngarluma people, where my partner works for the radio station. One of the most amazing things about this community is that it is the first one in Australia, or maybe even in the world, to win a court case over the native title to their land against an operating mine. They used their traditional songs in the courts, performing them as evidence for their connection to the land. Just imagine: poetry sung in court as evidence!

TL: It’s incredible. Apractice as proof.

AP: In the indigenous context, especially in Australia, the stories in these songs served as instructions for taking care of the land. They were passed through generations, and could contain different information about annual movement of species, landmarks, or weather anomalies. Over thousands of years, these stories led to the natural environment changing due to the repetitive activities of humans. It’s crazy to think about a situation where a cultural artifact can change the ecology of a continent.

TL: These are two contexts where a song became an object, behaved in different ways than a story does. Is this what you want to do with your storytelling?

AP: I’m interested in storytelling as a cultural concept, and as something that I consider one of the first technologies that humanity invented in order to store data and information. So I’m not only working as a storyteller – many of my works are actually about telling stories. I think that we are so blinded by the rapid pace of recent technological changes that we tend to forget that technologies like oral storytelling endure the most, and that they can outcompete any contemporary technology of information storing. It’s well-documented that there are still circulating oral stories containing information about geological events that took place more than 7,000years ago. There is no way of storing information that is safer than dressing it as an exciting story and singing it to your child. Because your child will sing it to their child. It outcompetes handwriting, electronic storage, even carving in stone, as Cixin Liu would like it. The only more durable data storage technology is RNA and DNA.

TL: When you make your stories in your work, are you thinking of the instructions that you are releasing into the world?

AP: Well, unfortunately, I don’t believe in such permanence of my work, mostly due to the medium. I don’t think that film is a particularly lasting medium…

TL: But as lasting as a song sung to a child?

AP: I would have to create a really good story to achieve this. I’m not sure if I’m there yet. I think that what an artist can create is an idiom –– something that enters language and becomes symbolic. Of course, when I say artist, I mean also a writer, a poet, a filmmaker, or a painter. An idiom is something that starts to circulate in society and changes it.

TL: About the longevity of storytelling as a technology, I was thinking about your interest in different durations of time. You often cast your eye really far back into history or into the future, and then bring it to somewhere close to the present.

AP: I am definitely interested in experiments with scale. And experiments in scale include experiments with time. We should mention Fernand Braudel, the French historian who created the concept of thinking about time not as one unified entity, but rather an interlaced mesh of different time scales where various objects and beings and ecosystems and civilizations have their own timelines that are somehow interwoven together, but still have their own pace. When I think about these experiments in scale, what comes to my mind is also the visual aspect of it, so experiments with noise. Visuals that can make sense as an image at a certain scale, but will become noise at a different one. I think that’s somehow connected to the scale of time.

TL: I wanted to ask about your interest in scientific disciplines in general. How do you arrive at them in your research?

AP: There are certain sciences that I’m interested in. I am interested in social history, cybernetics, and economy, but the economy of affect, not really economy, as such. And I try to combine these different disciplines to make a case for why I’m an artist. Like, what does it bring to society that I am an artist?

TL: Economy of affect?

AP: When I talk about economies of affect, I’m thinking about what Sarah Ahmed proposed in her work: the idea that emotions circulate in societies much like capital does, and that we can think about emotions and affect as entities that operate under laws similar to economic ones. Emotions can be quantified and stored. To me, an artwork is a unit of emotions. So when you think about how emotions such as love, fear, empathy, or hate circulate and regulate societies, and when you consider an artwork as a unit of emotions, then suddenly, art becomes crucial to society. In recent years, I’ve been developing this concept – rooted in an understanding of how systems function – as a way to justify my role as an artist.

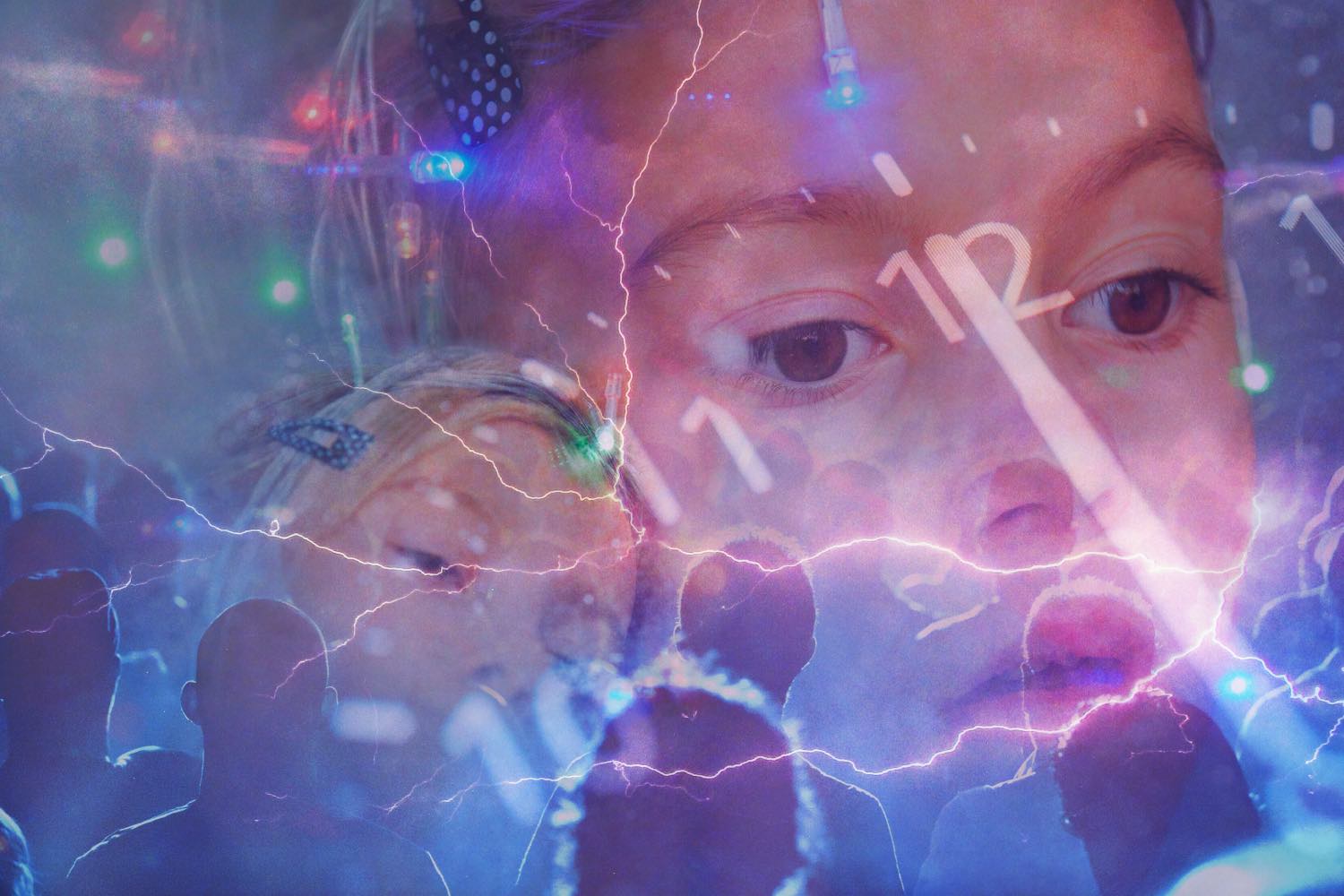

TL: In terms of emotional circulation, I found it interesting that some of the styles of audio effects and voiceovers that you use – like ASMR – are also really common in AI-generated content, reels, and TikTok. It feels like there’s a connection between these methods of storytelling that tap into our desires and the affects that trigger something in our brains. Do you feel like you were foretelling this trend by using these tools?

AP: I don’t think I was foretelling anything. I used these tools simply because I wanted to give the viewer something that they already wanted to hear; contemporary social media works on the same principle. My decision to use this particular material came from a desire to attract viewers. I wanted to create work that felt accessible, even if it’s highly abstract or poetic. It should be abstract, it should be complex in terms of its philosophical meaning, but at the same time, it should captivate – or even trap – the viewer in the room, watching another loop of the video. That’s why I began using popular tunes and stock materials that often reference existing songs, sometimes disguised as something new, or certain vocal styles like whispering. Of course, this involves complex post-production. t’s not as simple as some content you find online. Though I have this observation that much of contemporary social media content is far from simple; it often looks or sounds experimental.

TL: Can you talk more about recent technologies? Which ones have inspired or influenced you?

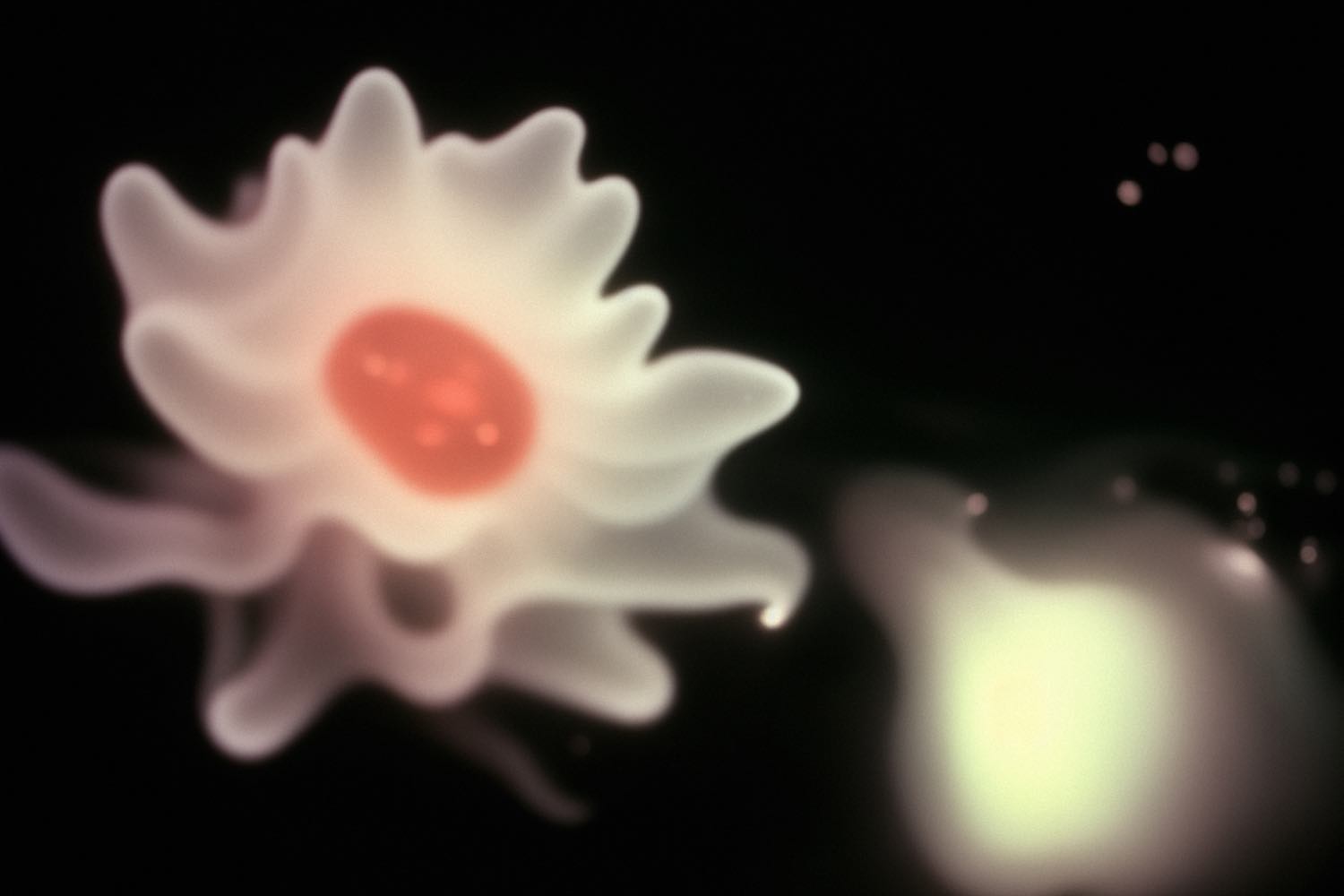

AP: Like many others, I used AI tools in film production and post-production over the past few years. For example, my recent film The Book of Flowers (2023) is based on found 16mm takes of blossoming flowers from the 1940s and 50s, but I replaced all of the original frames with AI-generated images. So it’s kind of an unusual found footage film. There’s no actual original material used, yet the movement structure is still taken from the original films.

TL: Are you saying something about the tool itself?

AP: This particular film is about storytelling understood as a technological tool. It presents a fictional history of reproductive symbiosis between plants and humans, evolving through technological progress. The narrator suggests that in the future, our stories might be better told by technological tools than by humans. I’m exploring the poetic idea of humans becoming secondary as storytellers.

TL: What do you think would make a technological tool better at storytelling than us?

AP: Story structures vary across cultures, but there are some universally effective, affective storytelling patterns. Human emotions haven’t evolved much over millennia, so it would be relatively easy for a non-human storyteller to master these rules and captivate us. In that way, we could be trapped in a fictional world that we’d prefer over reality. Even if the imagined world is dark and cruel, it can still feel pleasurable, because we don’t feel responsible for what we see. In the real world, we’re constantly confronted by very disturbing images for which we are somehow responsible, and that can create a reactionary desire to escape.

TL: Are you interested in making work that, through being entrancing and captivating, takes responsibility away from the viewer?

AP: In my work, I never allow that state to play out till the end. There’s an element of entrancement or captivation, but I use certain tools to disrupt it and alienate the viewer again. These can be simple – like humor, specific editing techniques, or a sudden shift in music – something that breaks that meditative state. What I’m specifically trying to achieve is dissociation. Through dissociation, the viewer might recognize they’re being manipulated. And that’s a crucial aspect of my work: I’m not trying to manipulate the viewer; I’m trying to expose the extent of manipulation that exists in contemporary media.

TL: You’ve mentioned storytelling in the form of singing to children. There’s also something childlike in how you hold a viewer’s attention, keeping them captivated like a child is by a story. And then there are the visuals. Are you specifically interested in media made for children?

AP: No. What you’re referencing is cuteness. It’s something I include in many of my works deliberately, and it’s definitely designed to attract the viewer,not just children. I think cuteness is a dominant cultural trait right now.

TL: Interesting. What do you mean?

AP: Cuteness has become a defining quality not just in culture but in all public spheres, including politics. Charming faces with big eyes, possibly covered in fur, have become an aesthetic canon. It ensures a sense of connectivity –– but also opens the door to manipulation. I think it’s connected to a deeper fear of the mind, something I believe is professionally called psychophobia.

TL: Psychophobia?

AP: Psychophobia is a fear of thinking. While some anti-intellectual tendencies are deliberate –– for instance, populist politicians pushing anti-intellectual agendas –– psychophobia is more subconscious. It’s a trend present in society that leads to a decline in the ability of abstract thinking. This is quite scary, because abstract thinking is essentially what distinguishes us from entities that prioritize only efficiency.

TL: Do you want to tell me about your next project?

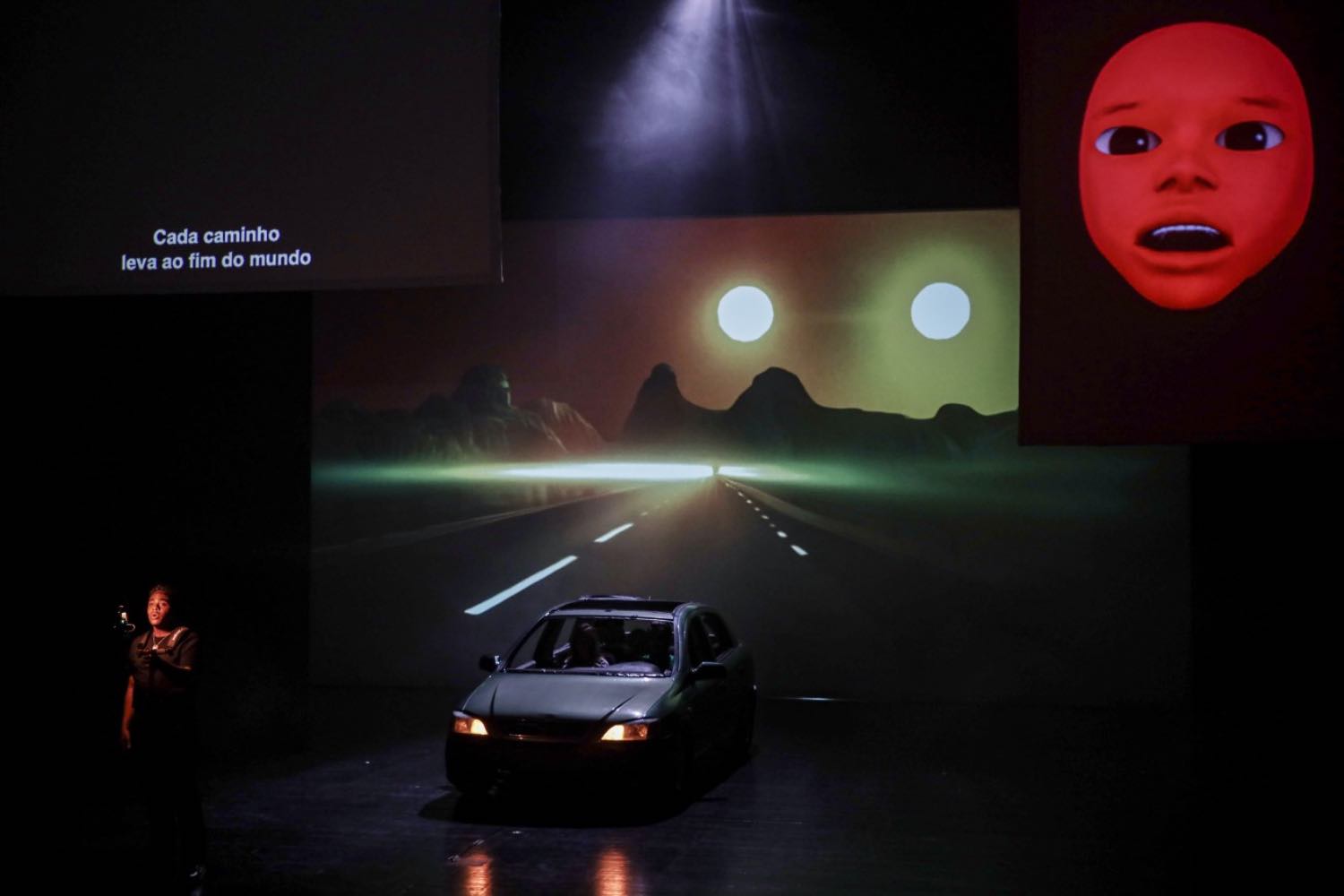

AP: I’m working on a cinematic adaptation of my theatre production The Talking Car (2023). Aside from that, my next project is a film I was commissioned to make for the Thessaloniki Biennale, on Nadja Argyropoulou’s invitation. I’m shooting it in Thessaloniki and in Indonesia. It’s my first live-action film and features very sparse dialogue. My work is usually very text-driven. I typically start with an emotional state and build text around it. But this time, it will be purely emotional, without the interference of language.

TL: What is the emotional state?

AP: As you can imagine, it’s hard to conjure anything positive in the face of the current, atrocious state of affairs. If I had to put this emotion in a sentence: Letting go of the collapsing world, and fearing the arrival of the new world order.