Artist Siyi Li prefers to go by only his first name in this text. “Like a pop star,” he muses. Or a unique individual (“There are so many Lis in the world,” he laments). Siyi works between sincerity and self-presentation — what it means to feel online, to live inside an image and somehow find beauty anyway. Post everything; call no one. Romanticize your life. How’s your nervous system doing now? Overshared, performed, real, and utterly ordinary, Siyi’s imagery is characterized by routine daily static, white noise in a world of technicolor spectacle. A bowl of soup, a hungover friend, a shirt that reads “Paris.” “I really loved that last DJ,” a character reflects in 新能缘 New Energy (2025), his recent fifteen-minute fashion-film-cum-travelogue. “Yes, I remember you went so hard on the dubstep,” another replies. Skeptical of the ecstatic show reality has become, something quieter emerges: when the fireworks die out (or never ignite), the spectacle burns off, the dopamine crash hits, and the shutter leaves an afterglow.

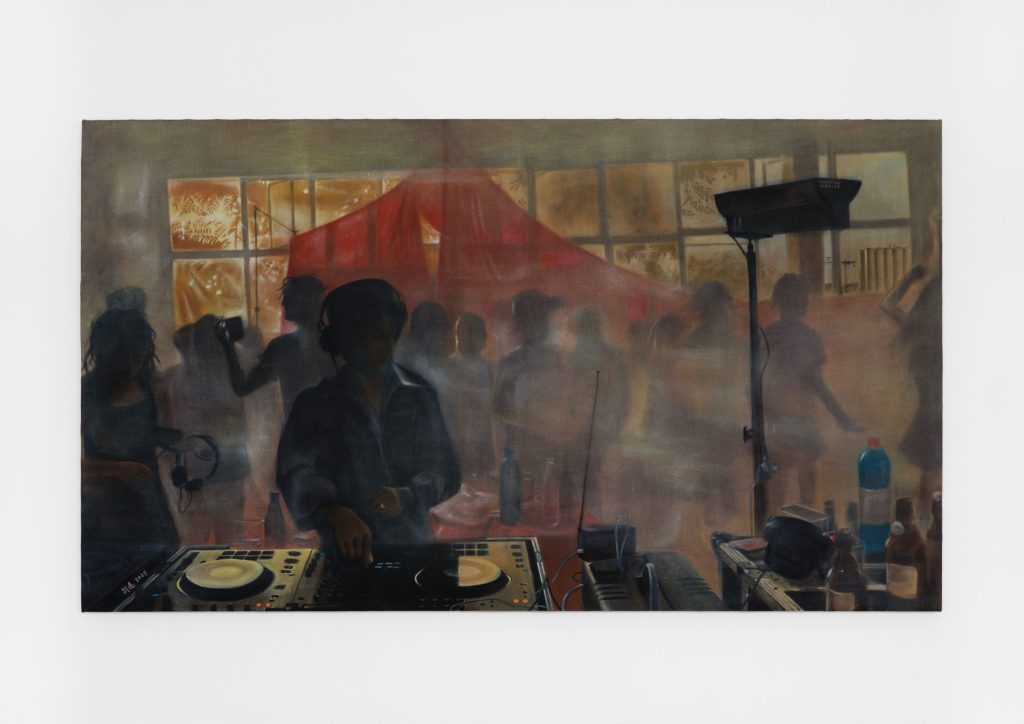

“The only people for me are the mad ones […], the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars.” It’s a magical line but a surefire risk to quote Kerouac’s On the Road (1957). Can a canonical book still be cringe? Think of 2000s teens blasting Death Cab for Cutie, clutching the rite-of-passage novel of American individualism and brooding masculinity. In the “I am cringe, but I am free” brand of existentialism, the normally pejorative term becomes generative for Siyi. He finds beauty in cliché, community in a hyper-stimmed audience of friends, and a semblance of aliveness in the mundane, where you’re the only one watching your own story.

In our present moment of ghosting rather than saying goodbye, his work renders an emotionally stunted, detached generation fluent in the cringe of “self-curation”: desperate, starved for and distrusting of unscripted presence. Articulating the tipping point when everyday aliveness just seems ungraspable, too minor to matter, Siyi’s practice scrambles the grammar of the grid that approximates authenticity. At the same time, his sincere approach suggests that the images we craft aren’t always about performing as someone we’re not. This isn’t nihilism. This isn’t even narcissism. It’s about figuring out how to feel in this global social landscape. Who — and where — are we if we’re not online?

It’s fitting that the artist, who lives between Shanghai, Frankfurt, San Sebastián, London, and Paris, encounters this condition of twenty- first-century existentialism on a road trip of his own. 新能缘 New Energy (2025) unfolds across five vignettes in which two characters in the backseat of an Uber change identities and storylines via stylized wigs and outfits (a Brat-green patterned shirt, a collegiate sweatshirt that says “Best Friends”). The work’s Chinese title has the double meaning of “electric powered vehicles” or new “destiny.” Perhaps it suggests we’re no longer the ones driving our own fate. Big tech and the algorithm are.

In Siyi’s work, online performativity is no longer the frenetic mania or cinematic campy horror of the Ryan Trecartin-to-Amalia Ulman-to-Jordan Strafer lineage. While those artists undeniably capture the unreality of our moment, Siyi’s self-conscious theatricality takes place upon an exceedingly, intentionally banal stage where his characters dialogue through a rehearsed empathy that can’t hide our loss of true connection. “Do not pretend to be ashamed,” one warns.

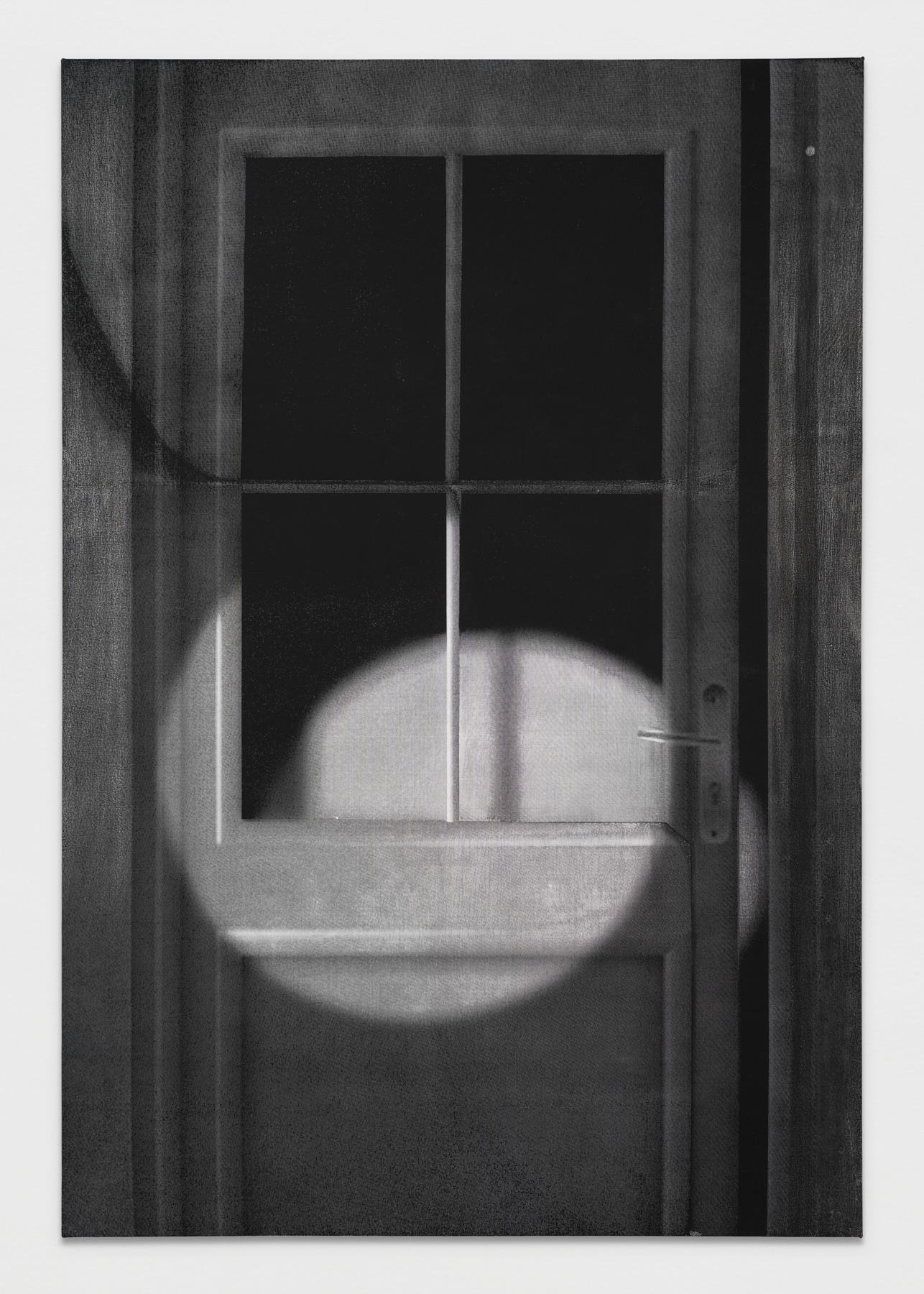

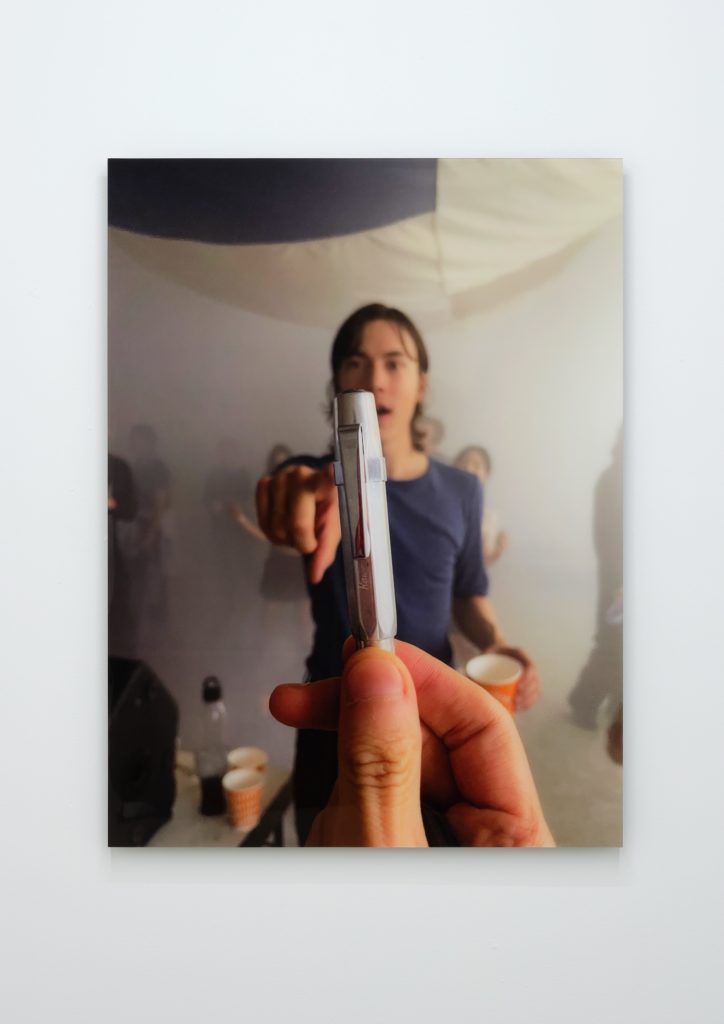

For the artist, images aren’t inherently evil. The danger comes when lived experience becomes an image detached from perceptual reality, cosplaying as material truth. The artist’s quaint motifs are often so earnest we would assume them to be ironic, but his sensitive hand carries a different psychological register of the lo-fi mundane. Unlike the adjacent “normcore,” his works wear a patina of ennui and trite joy or a nostalgia for an intimacy that existed before the internet literally took over our lives. Flower arrangements are laser-printed at home on wrapping paper, exactingly cut. Snapshots of friends translate into fashion editorial and intimate iPhone- size portait or still life. Cardboard canisters for fireworks and cement dynamite batteries wear stickers and charm bags; some “shoot blanks” in the silhouettes of tiny sparklers; others are taped with bouquets mimicking fake flowers clipped from magazine pages. Installed on the floor of his show “Adonis” at Antenna Space in Shanghai, the firework containers resemble small memorials, like sentimental ruin. What’s being mourned, perhaps, is the dream that the images we chase can hold the moment, can stop time’s progression while living for the JPEG attenuates the feeling of being real.

With an eye to historical Pop (e.g., Claes Oldenburg’s soft sculptures of quotidian objects or Jasper Johns’s “ordinary” symbols, like the American flag), Siyi’s sculptures launch a critique of images as vehicles of consumerism, qualifiers of masculinity, depictions of what our lives as human beings should look like and how global power moves. For instance, before fireworks, for instance, became a Western emblem of victory in sporting events and the 4th of July, they originated in ancient China, when Taoist alchemists mixed gunpowder in bamboo, hoping to create an elixir of eternal life. By the thirteenth century, Europe adapted the technology for war and military victories. Related to the firework sculptures, the artist’s solo show “Crybaby,” at Cibrián in San Sebastián, considered the snowflake as a multilayered cultural symbol. Embracing the snide euphemism for an overly sensitive Millennial and Gen Z “snowflake generation,” the work’s centerpiece, Teardrop (2022), is a giant snowflake suspended from the ceiling of the gallery. Drifting between fine art object, theater prop, and children’s craft project, the work’s lumpy surface of hammered aluminum and rivets suggests that fragility and vulnerability might be the strongest way through. The implied individuality of form — no snowflake takes the same shape — also seems to acknowledge how the microscopic, ephemeral beauty of the physical world can sometimes only be captured in an image — or an artwork.

While Siyi’s work uses multiple strategies of making, I’d argue the image itself is his medium. The snowflake obliquely references David Hammons’s 1983 Bliz-aard Ball Sale, a performance known mainly through its photographs of the artist selling snowballs arranged like common market goods on the street — a seemingly benign but racially charged stereotype embodied in modes of display. Like Hammons, Siyi asks where the work’s meaning resides: in the image, the action, or the relation between them? Translating his archive of unstaged smartphone snapshots into iterative formats, his work straddles the momentous and insignificant alike: the UN building and postage stamps rendered in pastel; the Twin Towers in a deep wash of cyanotype-blue paint; a large canvas resembling dorm room décor memorializes photos of partying friends. The latter is scaled to “history painting” suitable for Greek mythology, yet softly executed by hand. Here, one character wears a hat that reads “Bon Voyage.” What might this journey be? In Siyi’s practice, if the Odyssey of the past was the search for the miraculous, the present search is simply for connection that makes us feels something, anything remotely real. In contrast to photography or painting, the search for “truth” in the image- as-medium isn’t the physical trace of light or the artist’s gesture, but the psychic and physical trace of a fleeting memory. Siyi admits: “In all the photos, I think about my feeling when I was taking them — the loneliness, the excitement, the longing. That emotional truth is part of the work itself.” In a time when sincerity feels risky and at risk of becoming a trope, emotional truth couldn’t sound more radical.

As he interlaces cliché with subtext, a meta reflection appears: how images become readymades, how they move through the world, and how we move as images through the world as a result. Perhaps we continue to live through images not because of screen addiction but because it’s the only reality we know. If that’s the case, perhaps images can travel differently — not as commodities or tools of control, but as relics of living and cherishing the ephemeral that makes us human.

In this way, the artist retreats from the pageantry of grandiose mass individualism in favor of a more intimate, and sometimes wry, understanding of what emotional authenticity might look like when patriarchy doesn’t determine feeling. A wandering hero Siyi does cite and pushes against is Bas Jan Ader, whose In Search of the Miraculous (1975) mythologized the artist’s disappearance at sea while making a conceptual endurance work of “miraculous” proportions. Primary Time (after Jan Ader) (2025) is a cheery, living flowerbed bursting with color meant to decay over the course of the exhibition at Antenna Space that holds this reflection. Genuine or cringe? It’s ambiguous and that seems to be the point.

Siyi’s project is diaristic to an extent, but it’s also diagnostic, as he describes his work as context- specific rather than site-specific: a distinction significant for a world in which images shift meaning with every meme, repost, or advertisement. In one of his glossy fashion magazine diptychs, Untitled (2025), a selfie of the artist suggests an earnest moment of self-reflection in a dressing room mirror. The second image suggests a possible caption in two advertisements that read in German: “What do I wear to my ex’s wedding?” and “What kind of times are these?” The first belongs to a European fashion retailer; the second promotes an exhibition at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin. I guess “the emotionally aware museum” is still a thing these days. So, apparently, is the “performative male” who reads Sally Rooney and wears wired headphones (like those pictured in the work). Lightly critiquing the art world’s adoption of sorrow as a theme and sentimentality as a persona, Siyi isn’t saying we need to feel sad for museums or sad boys who claim integrity. But if we can’t cry for them, maybe we can cry for what got us here.

A final road trip closes this search. I started working on this text the night a friend drove through town for a visit. I went to share zucchini bread with him at a picnic table out back under a full harvest supermoon. He was using a child’s tiny watercolor kit to render a lawn chair with faded hunter greens. Said he’d recently deleted Instagram, probably would redownload it later. Said he was out of practice at watercolor. I said I wanted to photograph the moon but knew I couldn’t; I’d tried before many times. So his provisional painting would be a record of a reality that couldn’t be pictured. For Siyi, there’s no iconic claim to authenticity, only the faint sense of truth in the periphery of image culture. In that afterglow, maybe there’s a more honest place to start from — that acknowledges the small miraculous that exists outside the image, which the picture points to but can’t pin down. Sharing sweetness rather than nonchalant travel dumps might feel like breaking social rules. But if we dare to try, to exist beyond images and how things appear, we can perhaps find an antidote to collective emotional avoidance. But we can also admit: images are precious. Just imagine losing yours.