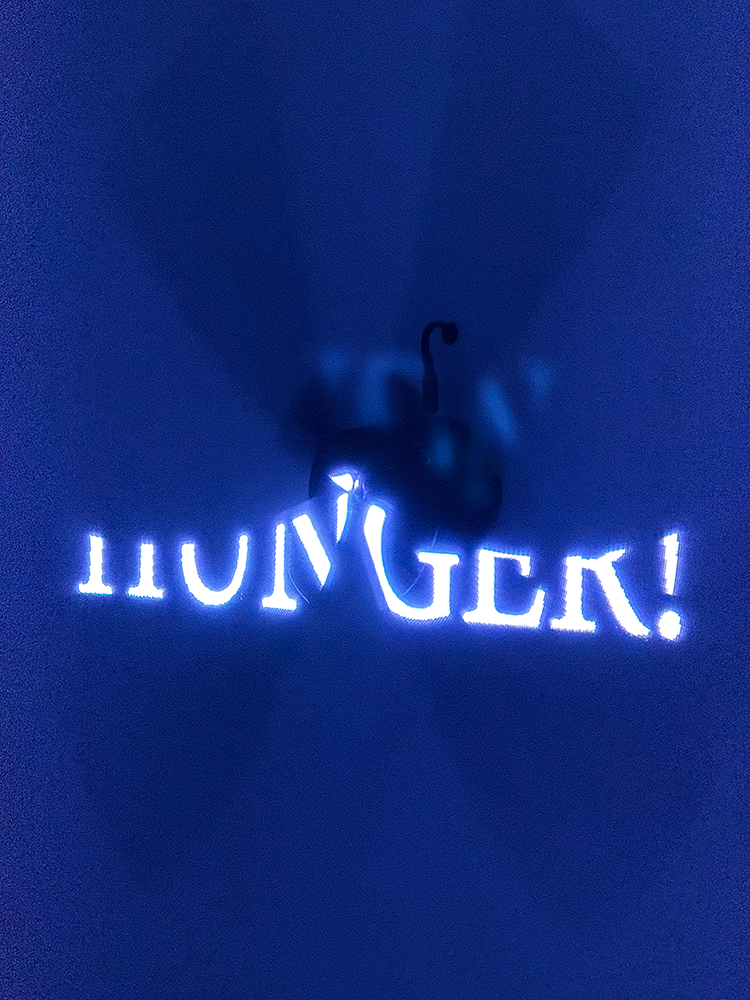

I arrived at “Grammars of Light” with the sense that I had chosen carefully. After skipping Art Basel Miami Beach last December in order to spend time with Lutz Bacher’s work, coming north for this exhibition felt like a continuation of that decision: to slow down, to see differently, to follow a quieter intensity. At the Astrup Fearnley Museet, Grammars of Light, curated by Martin Owen, brings together Cerith Wyn Evans, Ann Lislegaard, and P. Staff—three artists from different generations who all treat light not simply as a medium, but as a language in itself. Moving through the exhibition, light is never just something to look at. It becomes atmospheric, physical, and even intrusive.

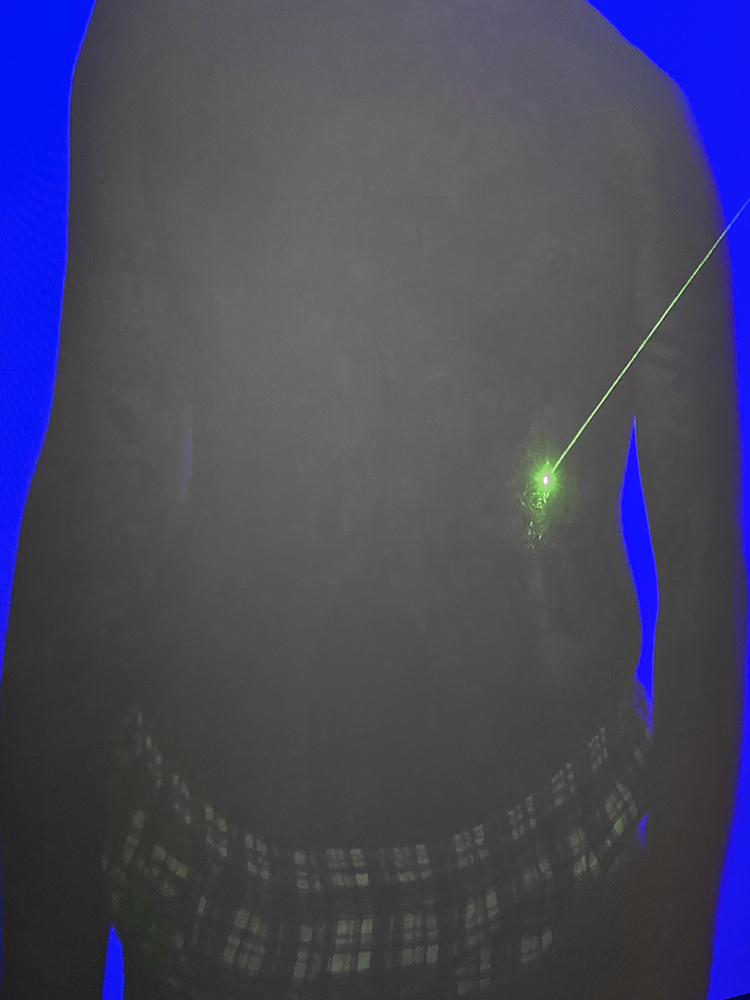

The exhibition opens with P. Staff’s Penetration (2025), a video installation that immediately unsettles. A medical laser is directed toward the abdomen of a monumental human figure, but the body resists easy identification. It doesn’t read as portrait, symbol, or allegory. What holds my gaze instead is the laser itself — its slow movement across the skin, and its entry into the body. The moment of contact becomes the subject. Watching it, I felt an uncomfortable intimacy, as if the boundary between exterior and interior had quietly dissolved. The body here is porous, open to forces that remain beyond full control.

Throughout the exhibition, the works respond closely to the museum’s architecture. Light columns echo the glass ceiling; projections stretch and adjust to the proportions of the galleries; holographic fans form a corridor of dense luminosity, carrying fragments of poetic text. Nothing explains itself. There is no didactic gesture. Instead, the works create situations — spaces that ask for slowness and a willingness not to immediately understand.

Cerith Wyn Evans’ StarStarStar/Steer (Transphoton) (2019), spread across two floors, felt almost architectural in its presence. The suspended pillars of light recall fluted Doric columns, evoking an ancient language of support and order, even as they remain untethered to the ground. At the same time, their material reality is unmistakably contemporary. LED lights pulse according to an algorithm based on chance operations, a quiet echo of John Cage’s compositional methods. Standing among them, I felt a rhythm without pattern and a structure without hierarchy register itself in my body.

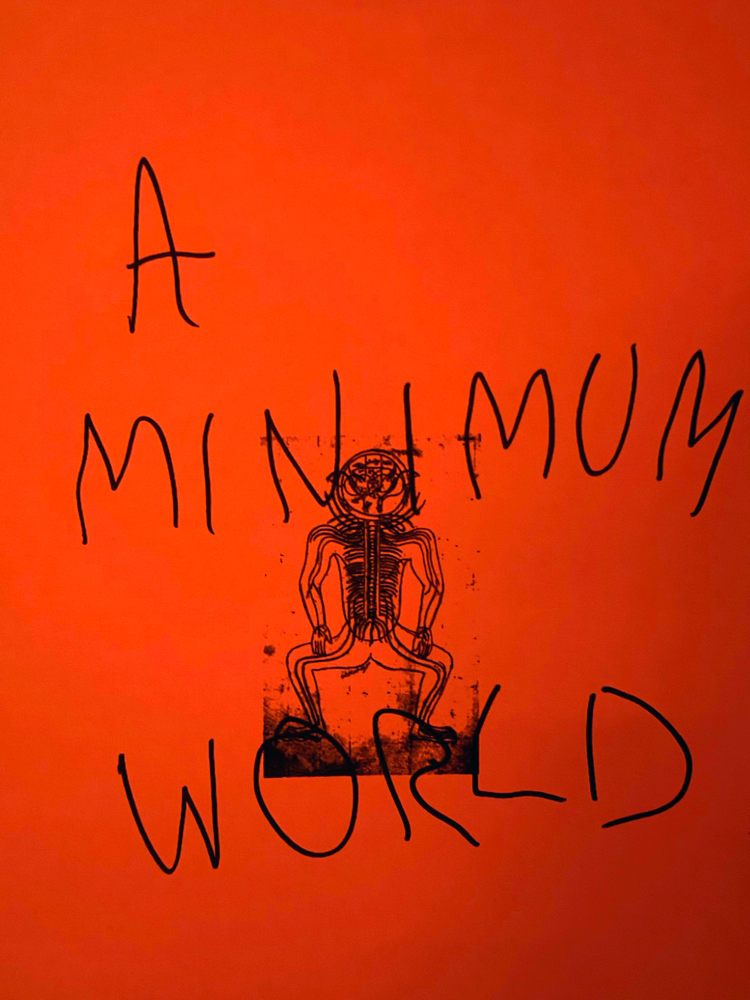

P. Staff’s Hormonal Fog (Astrup Fearnley) (2026) shifted the experience inward again — this time quite literally. The space is bathed in an artificial orange light, almost too sweet, verging on toxic. Organic compounds are released into the air, substances used in non-Western medicinal practices that suppress testosterone by intervening in the endocrine system. The idea that my body might be subtly altered simply by breathing fundamentally changed my awareness of the room. This is not a metaphorical intervention but a physiological one. The work gestures toward forms of bodily agency that exist outside institutional medicine — a charged proposition, particularly for transgender and queer bodies, whose relationship to medical systems has long been marked by control and violence.

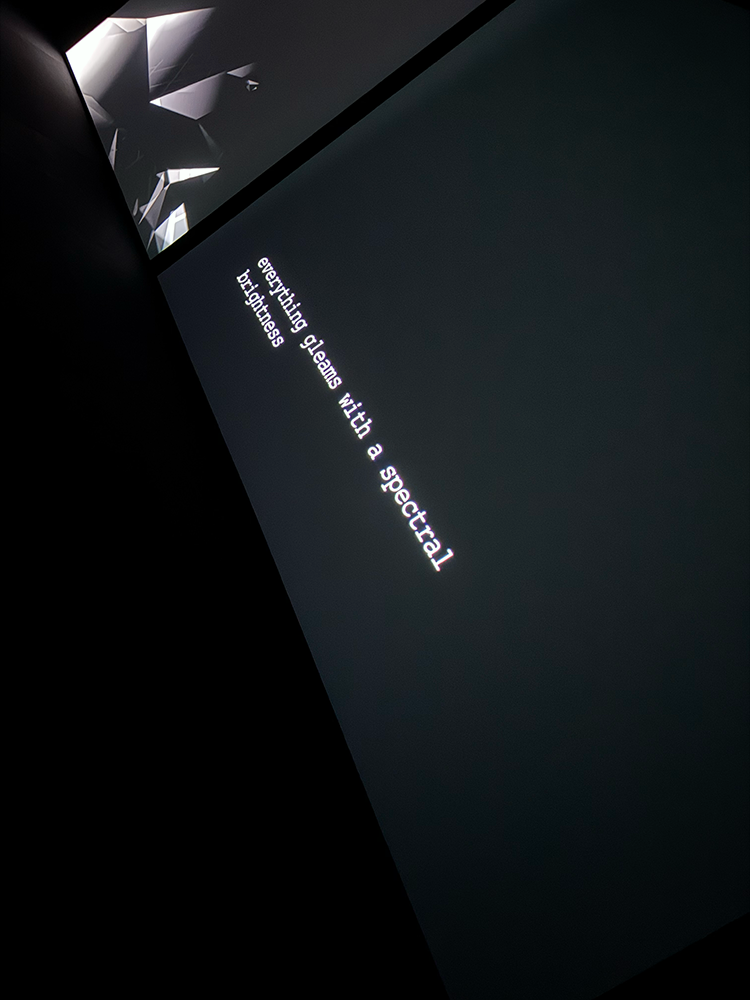

The exhibition closes with Ann Lislegaard’s Crystal World (after J.G. Ballard) (2006), and the shift in tone is palpable. Based on Ballard’s novel, in which the world crystallizes into luminous, faceted forms, the work resists spectacle. Instead of dazzling transformation, Lislegaard offers restraint: monochrome imagery, measured pacing, and shadowy spaces. After the intensity of the earlier works, this felt like a place to rest, to let attention settle on surfaces, edges, and absences.

What stayed with me after leaving “Grammars of Light” was not a single image or object, but a sequence of bodily sensations—brightness, warmth, disorientation, stillness. Choreographed in dialogue with Renzo Piano’s architecture, the exhibition allows the works to overlap and interrupt one another. Light echoes across rooms, bodies cross paths, and ideas momentarily converge before drifting apart. It is not an exhibition to be grasped all at once, but one that unfolds through movement, hesitation, and return.