“Ghost:2568,” the third and final iteration of the Bangkok-based video and performance series “Ghost,” builds on the city as both its site and its subject. While ghosts and spirits have long animated the artistic practice of its initiator, Korakrit Arunanondchai, the series broadens the ghost into a cinematic device and a formal strategy for rethinking storytelling within fragmented realities.

On the flight to Bangkok, I listened to a podcast in which the author and technologist Ken Liu described storytelling as humanity’s most advanced technology, our first tool for encoding knowledge and engineering collective reality. This idea stayed with me throughout the festival, which the curators referred to as a “song,” rather than an exhibition. I understand song as a technology that organizes experience through rhythm and repetition. And it’s true that “Ghost” was an experience that unfolded in layers of time as much as in space. Its story was carried by the rhythm of the many human and nonhuman city dwellers.

Its narrative was not linear but shaped by cycles of performances, weather conditions, and the movements of human and nonhuman city dwellers. The festival’s story emerged less through explanation than through pacing: anticipation, pauses, and an accumulation of gestures that revealed themselves over time.

I have been curious about this collaboratively curated gathering ever since its inception in 2018, and taking part in its farewell was my main reason to travel to Bangkok. Curated by Amal Khalaf with Arunanondchai, Christina Li, and Pongsakorn Yananissorn, “Ghost 2568 – Wish We Were Here” brought together an extended group of international artists, many of them with ties to the region, along with several alumni from previous festivals. Many visitors were friends, and the idea of a shared vision reverberated through the conversations — a sense that the festival’s “song” was not merely metaphorical but enacted through collective presence and mutual attunement.

I began my journey at the headquarters, located at Bangkok CityCity Gallery, which hosted most of the music performances and an arcade installation in which the local fashion label I Wanna Bangkok transformed the brand’s lore into video games. The player would always adopt the role of an alien goddess, haunting a school and fighting “bad boys.” The walls were decorated with Giant Game Cartridge Sculptures (2025), and the blinking lights on all the machines — including a vending machine selling “Ghost” merchandise designed by the brand — created a bustling atmosphere. I died three times before surrendering the controller to my travel companion, who finished all levels within minutes. The gallery’s second space housed Patience (2025), a vegetal installation by Daniel Lie with a hydra-like bouquet of wilted flowers whose warm, dusty smell was intensified by softly pulsating light. It was clearly a time-based work, an animated image, alive, or maybe dying. The tall windows were all draped with curtains. In the absence of explanatory meta-information, my mind wandered off to the geography of Indonesian shadow plays and the notion of windows as screens.

A lot of care was put into the location scouting. Among the very different spaces, from foreclosed corporate buildings and desolate private homes to chic hotels and galleries, the festival felt like a version of a world within a multitude of versions. Some of the narrative elements were stable, like the video installations, some more ephemeral, like the live performances or city tours (which unfortunately I missed). But the unique atmospheres, likely influenced by random factors like traffic and weather conditions, seemed to always be in tune with the artworks. One example was the busy intersection at the entrance to the Bangkok Art and Culture Center, which was the temporary home of Rirkrit Tiravanija’s augmented reality work untitled 2023 (sitcom ghost). The spectral figure remind me of all the potential encounters surrounding us in that moment.

In a desolate backyard next to one of the many canals, I was watching Jeanne Penjan Lassus’s A Jewel in the Mud (2025) when it started to rain heavily. The video’s calm camera lingered on ambient passages, diffuse shapes, and movements in murky water. For a long time I stared into the darkness and listened to the gurgle of water. I really wasn’t sure if it was the nearby river or the sound of the video. Organic and synthetic sounds merged as the rain silently crept through the cracks in the walls. In the video, I watched men in sports attire and improvised gear dive into the Chao Phraya River. The objects they bring to the surface have the aura of archaeological artifacts. There is a whole strand of works which deal with animated material and body memory, as in the project Rubber Dreams of Its Lifetime, a research project initiated by Bart Seng Wen Long and Kaisa Saarinen in 2021, and in Stephanie Comilang’s study of industrialized pearl production in Search for Life II (2025). Although quite different, these works reminded me that survival is a slow process. Like no other form, for me video makes this temporal dimension palpable. Film is itself a mnemonic medium, connecting us with this spiritual realm.

Everyone’s favorite venue was Baan Thewes, a reclaimed riverside house where a group of artists centering around the midwife Tarini Graham built a traditional birthing hut. Fragrant herbs (again) set the sensual backdrop for a deeply researched work that introduces birth not as a clinical process but as a ritual and, importantly, a communal effort. Much like the festival as a “song for human and nonhuman survival,” the work suggests that survival is, at its core, a collective practice.

Particularly interesting in light of this idea was the section Bodies Dispossessed organized by the previous edition’s curator, Christina Li. Here Li revisits conversations from past editions, bringing to life Orawan Arunrak’s Nirat of Parallel Rails (2025), which the artist had started working on after their first collaboration and during her stay at Delfina Studios in London. Inspired by the Thai poetic tradition known as nirat, the artist reframes the travelogue as a four-channel two-part video — at times augmented with live song. Installed over two floors at the Asvin Cultural and Contemporary Art Center, this work captures both the micro-gestures and the macro-conditions of continued migration of the artist’s presence and practice.

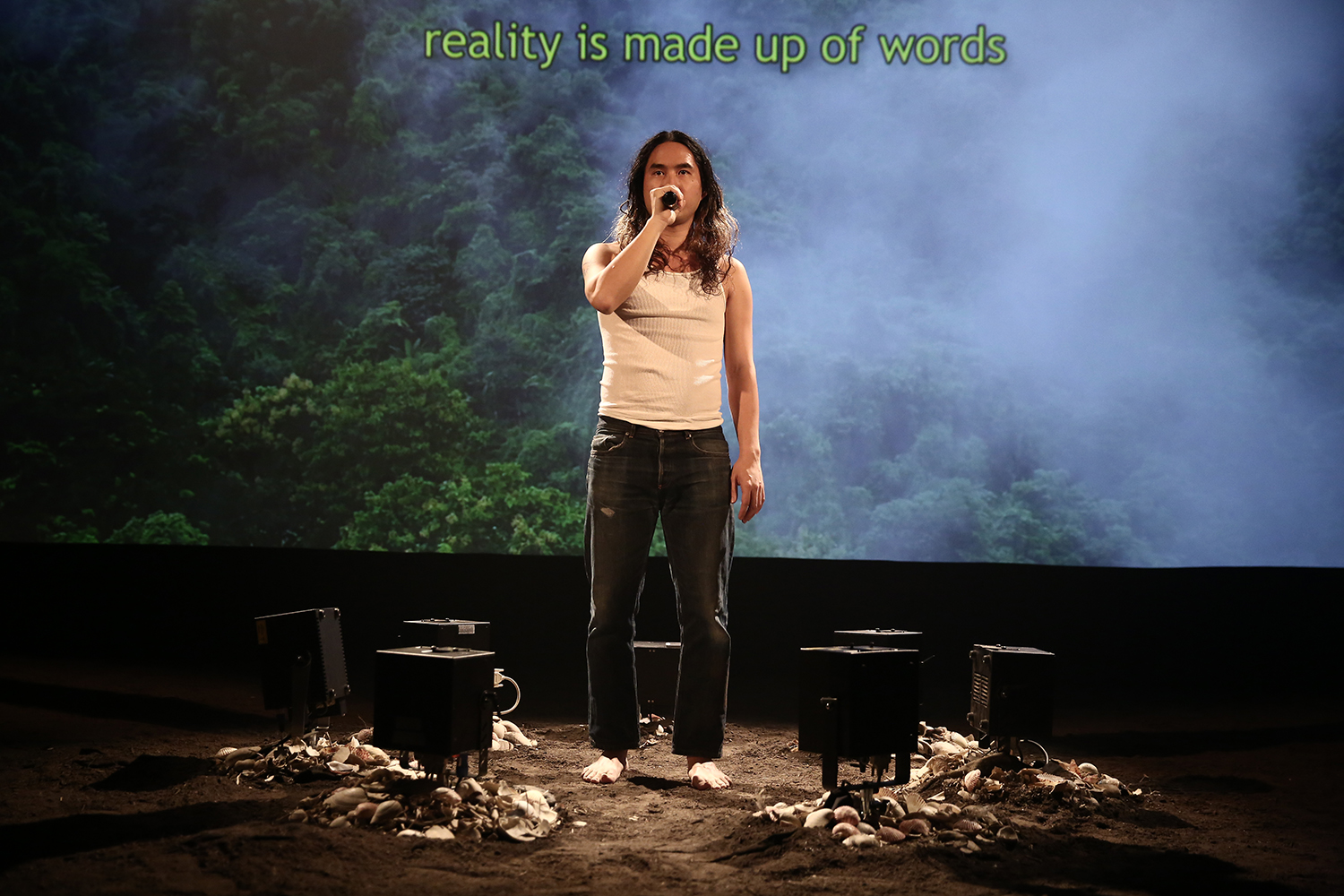

Back at the headquarters, a crowd had gathered to see Berlin-based dancer and choreographer Adam Linder perform Mothering the Tongue (2023), a movement meditation on repertoire and the survival of and within dance. Linder’s precise attention to gesture — its transmission, erosion, and renewal — echoed the festival’s broader interest in how forms persist and return. He was followed by Ashland Mines, who opened with a poem that plunged into a noisy sound field. His abrupt ending landed as a deliberate rupture, a sharp cut that left the audience momentarily suspended.

What stands out in this iteration of “Ghost” is the casual intimacy with which artists such as Linder and Mines present their work. Neither fully improvised, nor fully theatrical, the spirit of “Ghost” emerges from friendship networks. Mines’s long-term collaborator Ryan Trecartin is represented here as well with two video works located in the lobby of a multinational agricultural machinery company that faces a real-estate development on the other side of the street. Linder’s partner, Shahryar Nashat, presents his works Hustler_00.JPG (2025), Boyfriend_00.JPG (2022), and Lover_00.JPG (2023) as a trilogy adapted for “Ghost” at Dib Bangkok, reportedly the country’s first museum devoted to contemporary art. Although the museum has not yet officially opened, “Ghost” visitors were granted a preview of the future museum.

The festival’s greatest strength lies in the way its artworks are woven into the city’s lived flows, attuned to rhythm and embodied experience. Here, storytelling is not decorative; it is infrastructural. Like a song carried by breath and passed on through time immemorial, “Ghost” might end but it will surely persist. It might travel and merge with other narrative technologies, but we shouldn’t let it fall silent.