I spoke with architect Andrea Faraguna while he was in Milan. Born in Mestre, he earned his PhD at IUAV University in Venice and later worked with Francesco Venezia in Naples. For many years he has been based in Berlin, where in 2017 he co-founded Sub, which contributes to the conception of Balenciaga’s fashion shows and flagship stores, as well as major exhibition design projects, including Fondazione Prada’s “A Kind of Language” (2025). He now leads his own studio, pursuing research-driven projects attentive to architecture’s evolving cultural and environmental roles. Alongside teaching — at the Accademia di Architettura in Mendrisio and at the Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien — Faraguna has long collaborated with contemporary artists such as Anne Imhof, Isa Genzken, and Diego Marcon. His work, as he describes it, “explores architecture as a cultural and environmental practice, focusing on adaptive reuse, scenography, and behavioral design — how space can mediate perception, transform existing structures, and respond to shifting contexts across scales.” In May, he was awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Architecture Biennale for curating and designing the National Pavilion of the Kingdom of Bahrain: “Heatwave,” a climatic prototype for public space. More recently, he curated the unveiling of Versace SS26 by Dario Vitale at the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan. By consistently applying his architectural vision across diverse contexts, he has played a crucial role in shaping the aesthetics of the past decade.

Giorgio Di Domenico: Let’s start with something recent: the Versace show. The Pinacoteca Ambrosiana is a peculiar space. Founded in the seventeenth century by the Bishop of Milan, it was expanded between 1928 and 1931 with an unsettling intervention in ancient Roman style, including a very fitting Room of Medusa. In a city full of fetishized house-museums, you chose to transform this very traditional museum space into a sort of private home. Tell me more.

Andrea Faraguna: The idea behind the set design was to turn the museum into the illusion of a bourgeois residence. This staging began from the very first moment of the evening: all the guests entered through the service door, and many didn’t immediately understand where they were. We added only furniture and carefully selected props, just the right number of elements to suggest a cinematic narrative without transforming the space or making it hyper-realistic. The furniture evoked a multigenerational, familiar taste shaped between the 1980s and the early 2000s.

Each room had its own character, defined by function and evoking a possible fictional inhabitant. We imagined a house that had either been recently reopened or was in the process of being closed: there was an idea of maintenance — silverware laid out, waiting to be cleaned, paintings in the middle of being unpacked. At the same time, there was a sense of presence: someone had slept in the unmade bed. Among the furnishings were scattered some more contemporary clues that contrasted with the looks themselves, which were tied to an idea of lust and sensuality.

GDD: I was very surprised by the solitaire game left open on an abandoned computer screen. It worked as a kind of undefined historical reference, didn’t it? Something we perceive as belonging to the past without anchoring it to a specific moment — and the same time, it could have been a trace from the museum itself, the relic of a bored guard.

AF: Exactly. On the one hand, it was inspired by the museum’s sleepy atmosphere — it’s not one of the most visited places in Milan. On the other hand, solitaire is somewhat emblematic because the introduction of technological elements from different eras gives it a sense of historical indefiniteness: whether it is ten or twenty years ago or today, it could be today, but it is somehow suspended between these periods, without settling into a precise historical footing.

GDD: The idea clearly links back to the central role of domestic spaces in shaping Versace’s imagery. Perhaps more than any other designer, the home was crucial to Versace’s biography and stylistic identity.

AF: Yes, of course. As a child, more than the tragic moment of the murder, I remember the cameras entering the private rooms of the Miami mansion. In my memory, reaching the bedroom meant walking through a long corridor-like walk-in closet, and I remember being very impressed by this sense of ceremonial space, even a little inevitably tacky, but full of intent and personality. In some ways, we were inspired by it, but the idea was not to recreate a philologically correct space.

I looked at Gianni’s domestic world with my eyes half-closed. I tried to imagine it without relying too much on archival photos. Of course, we did look at some of the houses in Milan and Lake Como, but in the end, it was quite irrelevant. It was more a lyrical elaboration, an evocation — a way of finding the right register to let the images resonate. In the living room, two large rugs with a lyre at their center held the tone of the show, almost like the motif around which everything else orbited.

GDD: Earlier, you mentioned the flow of guests entering. I was wondering how these staging interventions affected movement, and if guests had opportunities to interact with the space.

AF: Fashion shows have a structure that is quite difficult to question. Upon entering, guests had a little time to explore the rooms before sitting on chairs and sofas that were also part of the narrative. It felt as if the house were preparing to receive visitors, but the visitors had arrived a little too early or a little too late, interrupting something, the private routine. Once seated, guests were left with the sense that they had not really seen everything — only fragments. It’s like visiting someone’s home: you see snippets and parts, you get an idea of this person through the details, but you don’t feel entitled to see it all.

This partiality was quite new compared to other things I’ve done in the past for fashion, which could be communicated with a single shot of the show. It was the first time I had done something so exquisitely theatrical and scenographic: pure set design. My work with interiors is usually less about decoration and more about provoking a different mode of attention — altering the way a space is perceived and navigated. In this case, that sensibility translated into a narrative register: not a plot in the conventional sense, but a sequence of spatial hints that allowed a story to surface indirectly, through what was revealed and what remained withheld.

GDD: You keep using cinematic language. Indeed, the whole operation sounds extremely cinematic.

AF: Absolutely. We managed to turn off all the museum lights. We introduced interior lighting and, most importantly, we installed very strong film spotlights outside. There was this light coming in through the windows, like the light of the city coming in at night — it created a beautiful atmosphere. Next to it, however, there were elements that broke the enchantment, such as the illuminated signs for the emergency exits. These were all elements we simply had to accept, and it was clear that it wasn’t a house, but somehow, at some point, looking at the details, the illusion worked.

We used many cinematic references: one we watched a lot was Todd Haynes’s Safe (1995), but also Eyes Wide Shut (1999), various films by Paul Schrader, and perhaps the way Luca Guadagnino used Villa Necchi Campiglio in I Am Love (2009). But the film that really guided us was Pasolini’s Teorema (1968), precisely with the idea of creating a bourgeois space, a capitalist environment that is interrupted and thrown into crisis by an unexpected guest –– in this case, the clothes from the fashion show. The soundtrack also featured a monologue from the film that Dario [Vitale] decided to include: Pietro, the bourgeois son, talking about the artist’s creativity in a way that is still very relevant today.

GDD Your decision to turn off all the lights reminds me of when we first met, walking through “Glassa,” Diego Marcon’s memorable 2023 exhibition at Centro Pecci in Prato. There, too, you had chosen to turn off the museum lighting, except for the emergency lights, and there, too, you had gone beyond the usual boundaries of exhibition design.

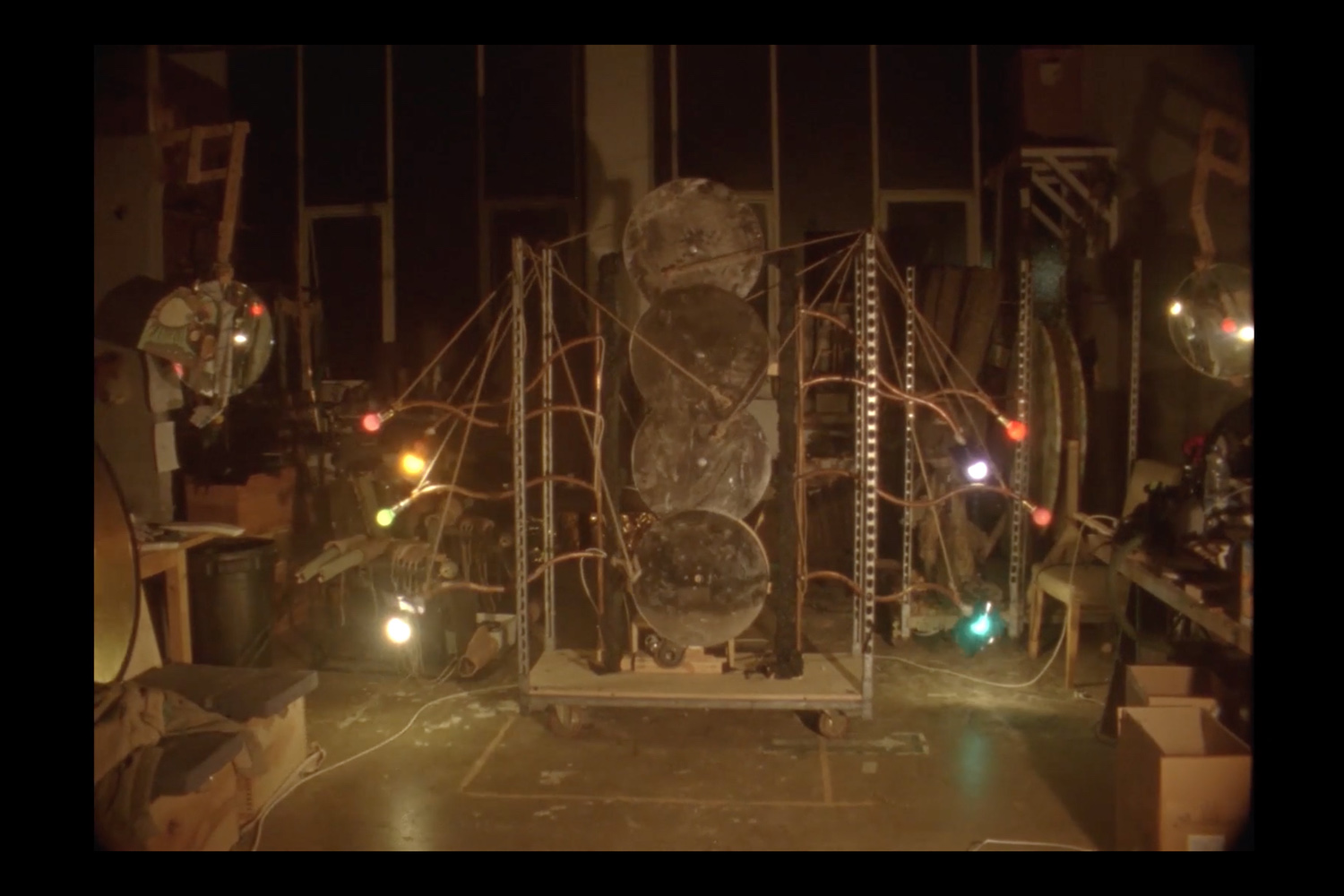

AF True! We even wanted to turn off the heating, but then it didn’t seem right –– we just lowered the temperature. The initial idea was to bring guests into an almost abandoned wing of the museum, so we did the bare minimum to create an atmosphere of intrusion. There were so few elements on display, and this is something I love about Marcon: he’s very good at not putting too much in. We also decided to open the huge window that allows artworks to be brought in on the first floor and replace it with a glass pane that opened vertiginously onto the courtyard. An image that came to mind when we were working on it was La Chambre, the 1952 painting by Balthus with someone theatrically opening a large curtain. That window was so large that it almost looked like the beginning of a theater performance.

GDD: How has working with artists influenced your practice? How do you approach them?

AF: As with fashion, working with artists happened by chance, quite naturally, living in Berlin. With Diego, and in a very different way with Anne Imhof, the starting point was always a conversation about the existing space. Each time the question was not only how the space could accommodate a “strange” presence — an unfamiliar discourse, a different temperament — but also how to expose the frictions that presence would create.

I’m interested in putting the hosting space slightly in crisis, disrupting the automatic idea of the museum as a neutral, welcoming container. If you invite someone, you also accept what their presence brings — the unexpected, the uncomfortable, the things you might not entirely want to hear. I don’t mean this provocatively; it’s simply the operative stance. Think of Imhof’s “Natures Mortes” (2021) at the Palais de Tokyo, or even the smaller exhibitions: the space is never a backdrop but an interlocutor.

GDD: For example, “AVATAR,” Imhof’s 2022 exhibition at Buchholz in New York, which really amazed me. You had to enter a very posh and intimidating building, and then you found yourself in a disturbing room with a low ceiling, surrounded by ugly lockers — a pure narrative glitch.

AF: Yes, the narrative glitch allows you to relax for a moment and take back some control over the space. Because when something works strangely — differently from what you expected — you activate yourself to understand what it is. It’s a way of bypassing the formality that every space imposes. Whatever the space, there is already a prescribed way you’re supposed to feel. Even if it’s not well designed or well anticipated, that prescription exists. So, offering an escape route and a shortcut to take control of a space in your own personal way is what interests me most. I think it’s really linked to the way I live, the way everyone lives in architectural spaces differently.

GDD: Ways of living in architectural spaces — this brings us to “Heatwave,” Bahrain’s pavilion at the last Architecture Biennale, for which you received the Golden Lion. I was surprised to read that you called it a mock-up, an architectural model transported into a different context. Another glitch. Can you tell me more?

AF: There was a whole series of fictional elements. What was on display was a mock-up designed for the exterior but placed inside, and that’s how it worked for the Biennale. There is too much to see at biennials, so I decided to focus on an architectural model, as large as the real thing, and stage a simulation of the exterior. But if you think about it, the project itself is the opposite: an interior space, but designed for the exterior.

It was the first time I approached sustainability, ecology, and climate change not as themes to illustrate but as conditions that shape spatial experience. What interested me was finding a way to transpose outside our idea of a comfortable place: a controlled, introverted environment, enclosed in an interior. After all, that is also a bourgeois approach. I wanted to take this and transfer it to the outside, to rethink a little what comfort is when we are not talking about private property, but public space.

So, in this case, it was about moving a room outside, removing its walls, and opening it up to any public scene. It was a very simple idea, but it raised many questions and thoughts about what can happen when, pursuing an idea of comfort, you open up a private space to unexpected guests.

GDD: I like this idea that returns in the various things we’ve touched on: comfort and discomfort, and how it affects the experience of guests. When you’re someone’s guest, you always feel somehow uncomfortable, and that was also an element of the Versace show: the museum, the visitors, even the clothes were all made uncomfortable by an architecture that was only narrated in fragments. In Marcon’s exhibition, the heating was turned down, the lights were off, and, also through the artworks, the guest/viewer was always meant to feel uncomfortable. And then there’s the idea of the pavilion creating a sense of comfort that is linked to social and climatic justice, by undermining (making uncomfortable, in a way) the usual bourgeois distinctions between interiors and exteriors.

AF: Yes, exactly that.