Ever since 2003, Loop Barcelona has unfolded within the city as both a constant presence and an ever-expanding inquiry into the mutable practice of video: a medium suspended between the architectures of cinema and the ever-shifting terrains of contemporary art, still wrestling for its own durable place. What began as a local initiative has, over time, unfurled outward, drawing an increasingly international constellation of artists, curators, and followers of the moving image, even as it remains threaded to Barcelona’s fabric of museums, foundations, and cinemas. Today, Loop articulates its approach thought three distinct yet interdependent branches: the fair, which occupies two floors of the Almanac Hotel in the Eixample district; a symposium that gathers thinkers, practitioners, and historians around the urgencies of the moving image; and a city-wide festival across the city.

This year’s edition—titled “Miratges Mirages” and conceived by Filipa Ramos in her capacity as Artistic Director of the Festival and curator of the Symposium—offered a doubling that gestures at once toward rootedness and outward drift, toward the intimate and the elsewhere. In her introduction, Ramos writes that “a mirage is a vision of hope and regeneration when it’s most needed,” emphasizing the importance of cinema and video and their singular capacity to reflect the present in its fullness — its histories, its frictions, its instabilities — and to enter into dialogue with it. A mirage is always a fleeting site of need: an apparition that hovers between illusion and revelation, between desire and the speculative labor of imagination. It is, after all, an image itself — brief or insistent — in which an “other” world momentarily appears. And what is cinema, what is video, if not precisely this threshold? The moving image is a realm where visions slip between the real and the fictive, the personal and the collective, the visible and the dreamlike — works that surface like fragments of the unconscious, shimmering but unstable, yet urgently present.

If mirages mark those fleeting thresholds where another world shimmers into view, the fair offered a kind of material counterpart to that idea: three floors of the Almanac Hotel whose rooms, darkened and reoriented, became small apertures through which such visions could surface. What might have seemed an unlikely setting — the hushed architecture of a hotel, its corridors of transience — revealed itself as unexpectedly suited to video’s shifting demands, creating pockets of concentrated attention in which each work felt momentarily suspended. Thirty-eight galleries, local and international, lined these passages, and moving from one room to the next became its own slow drift through atmospheres and sensibilities. In one, Saodat Ismailova’s Her Five Lives (2020), presented by ángels barcelona, mapped the evolving figure of the Uzbek heroine across a century of political upheavals, its essayistic form reading cinema as repository of shifting national imaginaries. Anne Barrault presented Rayane Mcirdi’s Après le soleil (2024), which follows a family’s late-’80s journey toward a homeland half-remembered, its pastel wistfulness hovering between fiction and documentary. At Galerie Alain Gutharc, Nelson Bourrec Carter’s Teen Spirits (2025) cast adolescence as a tender, collective rite, its choral structure amplifying the fragile emotions of that in-between age; while Mirna Bamieh’s A Brief Commentary on Almost Everything (2012), shown at Nika Project Space, slowed a single yawn into near-stillness, revealing how even the most ordinary gesture can acquire unexpected resonance.

From this wide field of visions and their mirages, the path drifted — almost unexpectedly — toward the Museu Tàpies, where a major retrospective of Germaine Dulac unfolded in parallel to the festival. Though the show itself stood outside Loop, its newly published catalogue entered the programme through the fair’s series of book presentations, creating a quiet bridge between the week’s contemporary reflections and Dulac’s early, uncompromising experiments. The retrospective, the first of its scale in Europe, deliberately bypassed La coquille et le clergyman (1928), allowing other films to surface with renewed clarity. What emerged was an artist who sought a cinema freed from narrative obligation, attuned instead to pure movement and the intensities that shape perception. Seen now, these works feel startlingly present—films that breathe at the threshold between abstraction and lived experience.

At the Centre Excursionista de Catalunya, Karrabing Film Collective’s Night Fishing with Ancestors (2023) unfolded in a dim assembly hall whose old portraits seemed to hover at the edges of the screen — an apt setting for a film attuned to submerged histories. “Karrabing,” meaning “low tide,” names the moment when what is hidden becomes visible, and the film follows this rhythm: six chapters tracing a line from pre-colonial Indigenous-Macassan exchange to the rupture of European arrival and the ecological urgencies of the present. Made according to the Collective’s motto, “NO STORYBOARD NO SCRIPT,” it layers fiction and documentary into what they call the “ancestral present,” where past, present, and imagined futures briefly surface in the same tide.

Joan Jonas’s early films offered a different kind of elemental encounter at Museu Picasso. Wind (1968), silent and shot in 16mm, unfolds on a snow-blanched beach in Long Island, where Jonas and a small group of performers advance against a force that cannot be seen but is felt everywhere. Their gestures are choreographed by the gusts themselves. The wind becomes the invisible director, turning the scene into a theater of resistance and surrender. Songdelay (1972), shown in the second room, opens the frame outward into the urban landscape of Manhattan. Here, performers move through the city’s edges, striking wood, tracing arcs on the ground, producing sounds that drift out of sync with the image. Delay becomes a method of estrangement: space and time slip from alignment, and the city emerges as a stage where perception fractures, expands, and recomposes itself.

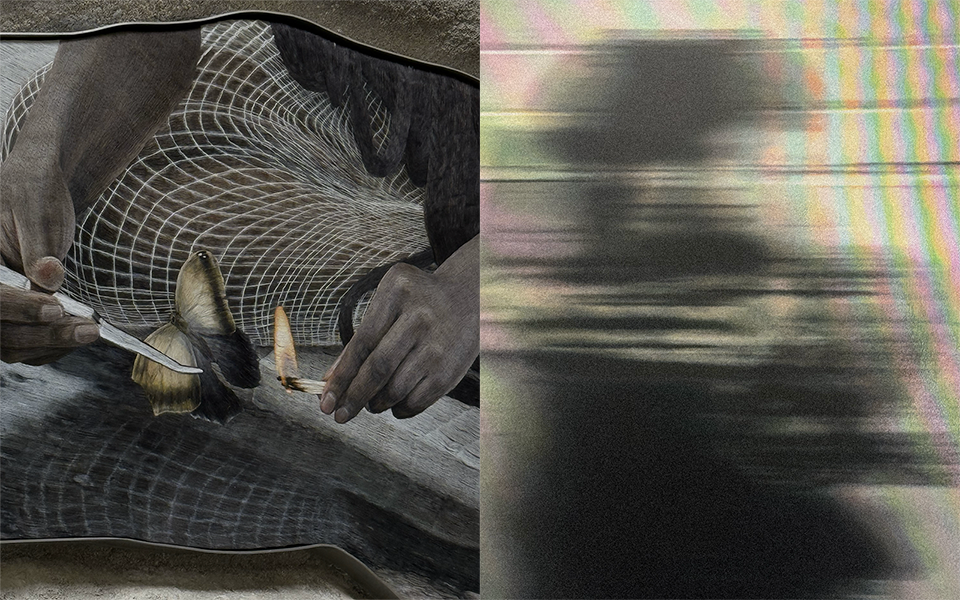

Natália Trejbalová’s Never Ground, 2025. Installation view at Hospital de Sant Sever, Barcelona, 2025. Photography by Nereis Ferre. Courtesy and © Loop Barcelona, 2025.

The festival’s final gesture — or at least its quiet afterimage — materialized in the fifteenth-century Hospital de Sant Sever, now home to the Casacuberta Marsans Collection. Here, Natália Trejbalová’s Never Ground (2025) probed what lies beneath the surfaces we traverse without thought. Filmed between the volcanic terrain of Vulcano, a cavern in Veneto, and a studio where sculptural props are assembled into speculative architectures, the work imagines the Earth not as a stable plane but as a porous, breathing sphere riddled with cavities and connective channels. The film builds like an underground epic, rising toward an efflorescent, almost otherworldly eruption — a creation event that is both alien and intimately terrestrial — before circling back to the exterior landscapes from which it began. Using science fiction as a tool for inquiry, Never Ground is a reminder that what we call “the ground” is neither fixed nor singular; that the surface is only a threshold; and that the unseen strata beneath us may shape our world far more insistently than what appears in plain sight.

In its many rooms, halls, and subterranean chambers, Loop unfolded less as a sequence of screening than as a taxonomy of thresholds: between past and present, surface and depth, visibility and what flickers just beyond it. In its own register, each work pressed the limits of what the moving image can hold — its capacity to remember, to unsettle, to reimagine. It’s as if the festival traced a constellation of mirages to show that such apparitions are not illusions but invitations, brief openings through which other way of seeing and living might come into view.