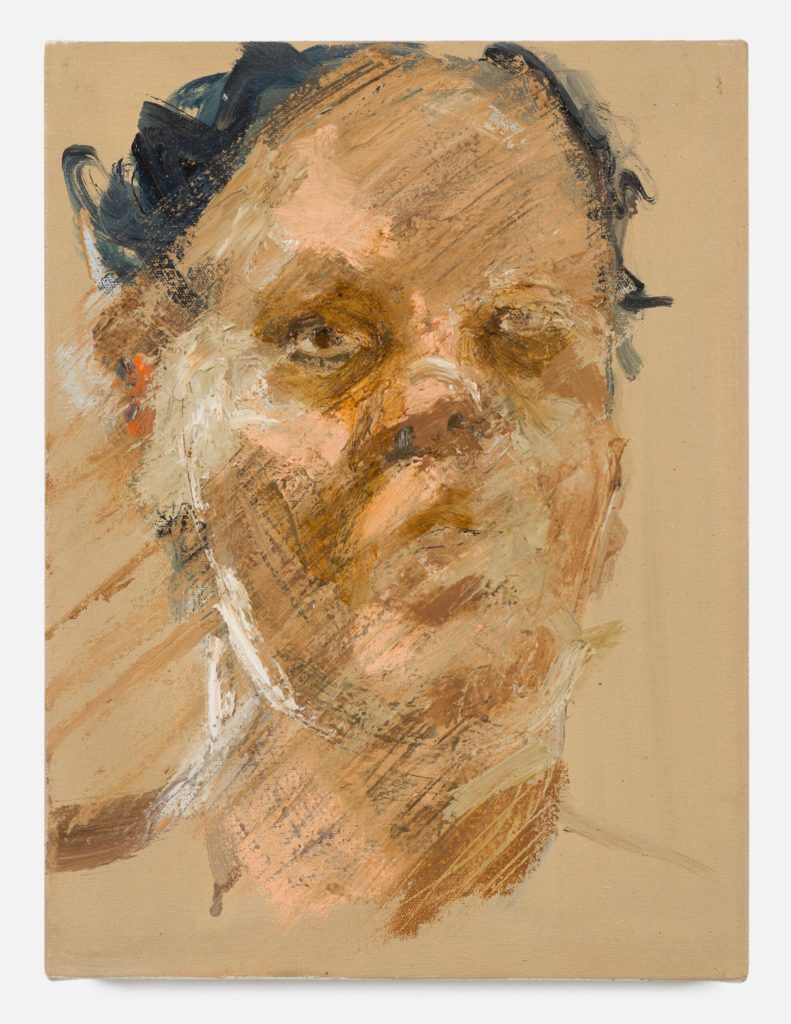

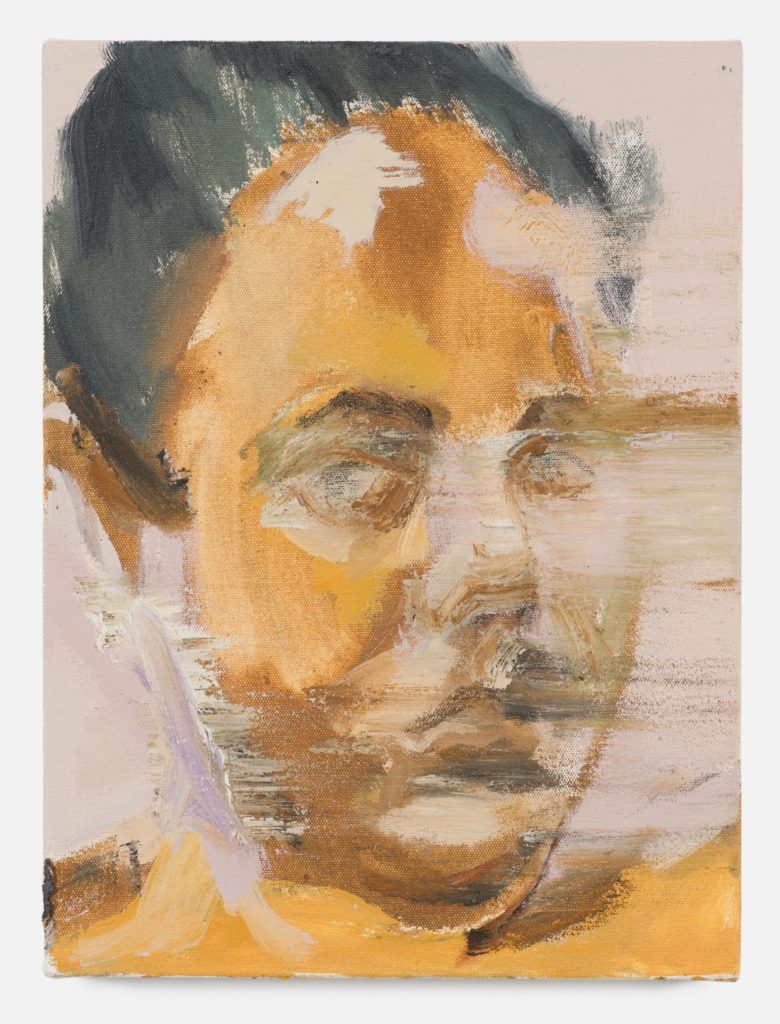

Márcia Falcão’s solo show “Corpo de Cor” (Body of Color) at Contemporary Fine Arts in Berlin is unexpectedly somber. Though it often depicts scenes of leisure — yoga, dancing, capoeira — these moments of recreation are shadowed by tension and unease. She paints mostly solitary Black female figures, some in discomfortingly contorted poses or in disjunctive fragments. As a whole, the show, comprising eight large paintings and a series of twelve small portraits, all made in 2025, conveys the sense of a Black female body struggling to assert its sensuous vigor.

In the two oil paintings that open the show, Position 25 (2025) and Position 24 (2025) from the “Psychological Yoga” series (2025), the female nude gives the impression of being cramped into the frame, its curvaceous shapes filling the canvas, pushing against the edges as if to burst from it. Crouching low or leaning back, the figures strain and hunch rather than repose. Falcão’s heaped volumes and streamlined geometry faintly echo cubism. Yet her canvases also fracture and reassemble perspective in ways that feel more sensuous than analytic. As a result, compared to her lush, tensed, performatic nudes, classic cubist renderings are relatively static. Falcão infuses her nudes with warmth, pairing ochre shades of the body with vivid purple and smoky-blue. The series title also points to something deeper: yoga as a metaphor for the psychological labor of women — for how effort, endurance, and self-discipline shape their sense of embodiment.

In this sense, yoga, as an immersive practice heightening awareness, serves as a metaphor for a broader experience of womanhood. In Position 23 (2025), two bodies share a bed or mat. One woman arches backward, head inverted, a leg bent as if in bridge pose; beside her, a muscular figure holds a downward dog. The warm yellow light, contrasted with the bodies’ dark contours, lends the scene a quasi-voyeuristic air. Though not necessarily erotic, the work captures an air of exhilaration in the vaulted poses, while also hinting at unease in the distorted female torso and mask-like face. There’s a tad of Francis Bacon in the work’s mixture of carnality and contortionism, its claustrophobic enclosure recalling the British artist’s expressionistic caged-in portraits.

Festive performativity is a leitmotif throughout the show, for instance in the paintings Chapa (2025) and A Negativa (The Negative, 2025) from the series “Capoeira em Paleta Alta” (Capoeira in High Palette, 2024–), which refers to the dance-like Afro-Brazilian martial art, and in Passinho Real (2025), the title referencing passinho, an improvisational street dance performed to funk music, developed in the poor communities of Rio de Janeiro. In all these works, Falcão captures the force of bodies meshing together, while also often hewing to murky, even muddy tones, bringing out an uncanny gravitas in quotidian scenes.

In other paintings, Falcão radically plays with scale. Pêndulo (Pendulous, 2025), from the series “Monumentals” (2025–), at first appears as a milky, uniform expanse of billowing cloud-like shapes. Yet, viewed from further away, there emerge contours of pendulous breasts and an expansive stomach. As elsewhere in the show, Falcão distorts the female body so that it becomes more like a landscape in its horizontality. On the right side of the painting, the body-landscape contains within it a smaller cluster of ochre shapes, which, once seen up close, turn out to be a grouping of brown bodies.

A similarly quixotic insertion appears in another large canvas, painted in smudgy charcoal-blacks: the murky and foreboding Cuidado (2025), also from the “Monumentals” series (2025–ongoing), which depicts a woman’s body from a sharp angle, as if looking up. A child, its mouth agape, clings to the mother’s side; a trickle or cluster of bodies blooms on her chest. “Cuidado” can be translated as “care,” or as an imperative, “be careful” — an aptly ambiguous title for a work in which the female body appears to have lost all the warm vitality present in the yoga and dance works, here replaced by a faceless, steel- or marble-like monumentality. By engulfing the individual body in color, Falcão transforms form into critique. Her monumental figures expose how Black women’s bodies have been used as vessels of care yet denied self-determination and pleasure.