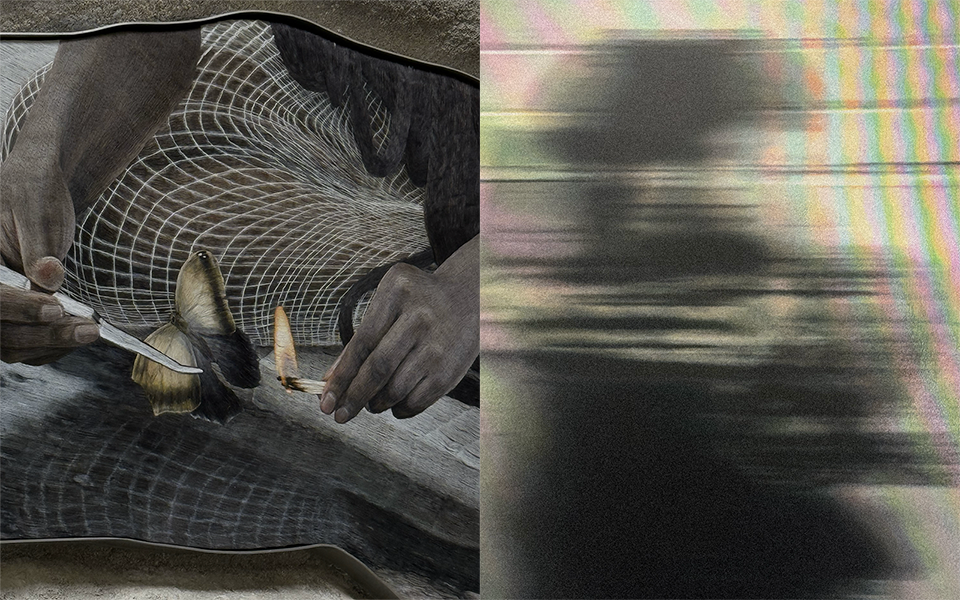

Afterfire, 2025. Installation view at Plicknik Space Initiative. Photography by Sam Hutchinson. © Minor Attractions 2025.

There’s a certain fatigue that often accompanies the mention of an art fair: the rows of booth presentations, the hum of transactional chatter beneath the glare of LED lighting, usually set in a convention centre. An artist’s assistant once described an art fair to me as “a butcher’s shop,” and it’s hard to forget this analogy that conjures up a sense of dismemberment: art priced and portioned for consumption. Yet, inside The Mandrake Hotel in Soho, London, during Minor Attractions 2025, the metaphor no longer fits.

Now in its third edition, the Minor Attractions fair feels highly sensory and immersive, even disorienting. The Mandrake’s corridors are dark, lined with velvet, and filled with drifting sounds of dance music. Moving through the building, one expects to enter a hotel suite, only to find an art installation, in a space where familiar domestic interiors and aesthetic encounters collapse into one another. It’s this slippage that gives Minor Attractions its charge.

Co-founded by Jacob Barnes and Jonny Tanna, Minor Attractions brings together contemporary art, performance, music and cinema into a week-long art fair. With seventy participating galleries – almost double last year’s figure – spread across fifteen hotel rooms, the fair’s expansion speaks to its ambition. Unlike the anonymity of convention halls, the intimate hotel format of contained rooms demands a slower pace and more interactive viewing experience.

The participant list stretches across continents, from London to Mexico City, Tokyo, Sydney, Toronto, Los Angeles, and across Europe. This year’s edition partners with Soho Radio for interviews with figures in the industry, music performances and features a film programme curated by Red Eye, the Southwark-based artist-run collective. Throughout the week, screenings began with Los Hongos (2014), a tender and defiant portrait of two young men navigating art and activism in Colombia, and ended with a screening of Rungano Nyoni’s I Am Not a Witch (2017) which shifts the tone as a Zambian fairy tale that moves between myth and reality, rooted in the oral storytelling traditions of Africa while speaking powerfully to systems of gender, belief, and freedom.

Walking up the Mandrake’s stairwell, visitors encounter works presented by House of Bandits (the Sarabande Foundation’s experimental gallery). Among the standouts is Overflow (2025) by Giulia Grillo, also known as Petite Doll, with a print composed of interwoven stripes of words, including “images”, “love” and “right”. Spliced in its collaged format, the sentences are fragmented to make different meanings. Nearby, Izaak Brandt’s Storm in the Mind (2025), a rotating bronze sculpture of a squatting figure from his “No Place Like Home” series (2024–25), which turns gently on its axis, folding inward in a collapsing gesture. The work is a meditation on the cyclical rhythms of grief and endurance.

Down the corridor, IMPORT/EXPORT presents British photographer Juno Calypso’s series of uncanny portraits: doll-like faces of women warped by water droplets and mirror reflections, their exaggerated features create a sense of unease. In a quieter register, London-based gallery Cedric Bardawil shows a self-portrait by painter Hannah Tilson, rendered in fluid swathes of watercolour pigment. The figure seems to dissolve amongst folds of fabric, blurring the line between figure and ground.

Nearby, Lindsey Bull’s large-scale painting Dance Studio (2024) depicts a lone woman standing in quiet reflection within a mirrored dance studio, the perspectival lines and mirrored walls expanding the sense of space while deepening the work’s meditative stillness.

Elsewhere, Isabelle Young’s intimate photographs of Italian interiors – some taken in Venice, others at Casa Mollino in Turin – trace the atmospheres of different domestic spaces. In another suite, Swiss gallery Fabian Lang presents paintings by Johnny Izatt-Lowry alongside small-scale 3D-printed sculptures by Victor Seaward. The latter’s works verge on the surreal: in the hotel suite’s bathroom, a hyperreal peach appears where a mirror should be above the sink, framed in an ultramarine reliquary-like box.

In the courtyard, Palmer Gallery showcases Madeline Ruggi’s looping sculpture, its rollercoaster-like composition is cast from tyre tracks. The work’s spiralling form carries a sense of momentum and abrasion, a choreography of material that feels both playful and tactile.

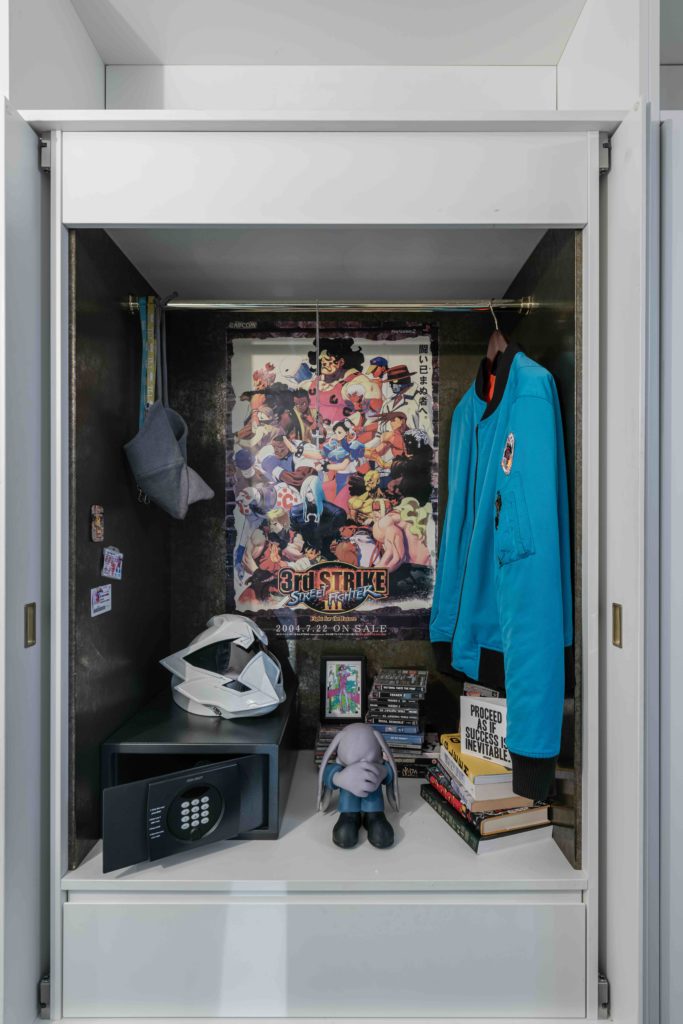

Meanwhile, Bolanle Contemporary presents Ramone K Anderson’s Moving On Swiftly, a deeply personal body of work meditating on loss, release, and the difficulty of letting go. The show is urated as a wake, with a shrine-like installation of a stereo, hanging clothing and CDs, and inspired by Jamaican Nine Nighttraditions. All of the subject matters in Anderson’s do not have any facial features, yet their clothing and surrounding interior spaces are defined. Each canvas has an almost devotional quietness.

In another hotel room, General Assembly shows a pair of paintings by Ranny Macdonald titled Let It Be on Earth and As It Is in Heaven (both 2025), which turn the gaze of the everyday inside out: the viewpoint in one painting peers downward, beneath the paw of a dog in stride, while the other draws the viewer upward, into the effortless drift of a pigeon gliding over a landscape.

In the Mandrake’s Ginkgo Suite, Tache Gallery presents new paintings by Lily Hargreaves, who depicts organic forms including tomatoes and celery, rendered in a way that stylistically gestures towards Futurism and the engineered forms of Precisionism. Her works sit alongside a monumental fantastical dollhouse installation by Amélie McKee and Melle Nieling of Plicnik Space Initiative. The sky blue house expands across the suite, its toy-like nature and uncanny details create a surreal environment that feels equally playful as it does disquieting.

What makes Minor Attractions remarkable is the way these presentations speak to one another. Across rooms, an engaging thread of connection forms between artists, geographies, and subject matters. The fair remains experimental without being obscure or inaccessible, reimagining the art market as a collaborative ecosystem, and open to inventive modes of presentation.

By inhabiting the very intimate, atmospheric architecture of The Mandrake, Minor Attractions insists that art should not merely be consumed but entered, inhabited, and felt. In that sense, it succeeds where some fairs might falter. At times, it can be difficult to distinguish between the fair’s installations and the hotel’s own elaborate decor. But the fair excels in its curatorial programming and immersive setting, and its charm lies in its playfulness. It revels in experimentation, with surprises at every corner, and it doesn’t take itself too seriously, making the experience both stimulating and delightfully unpredictable.