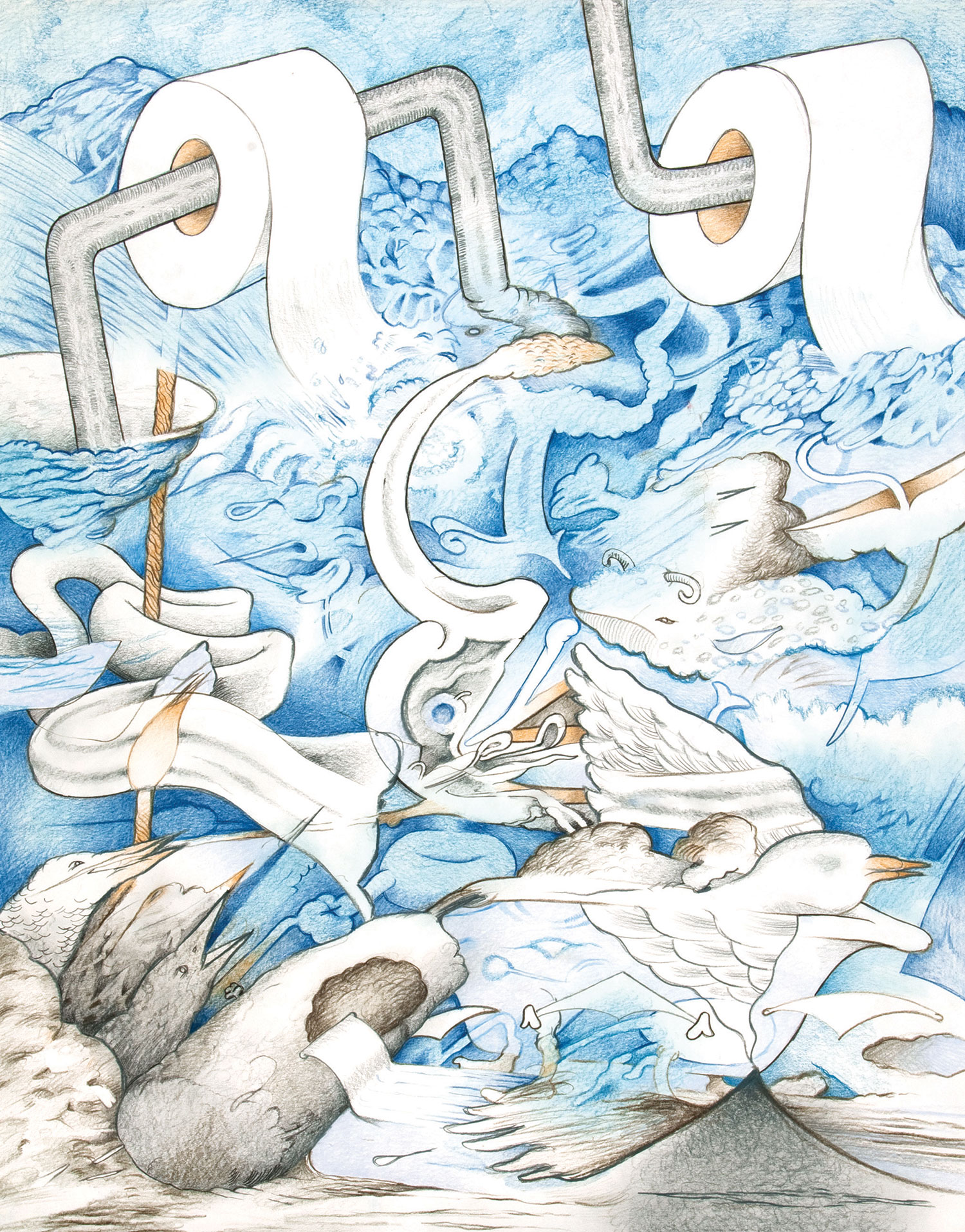

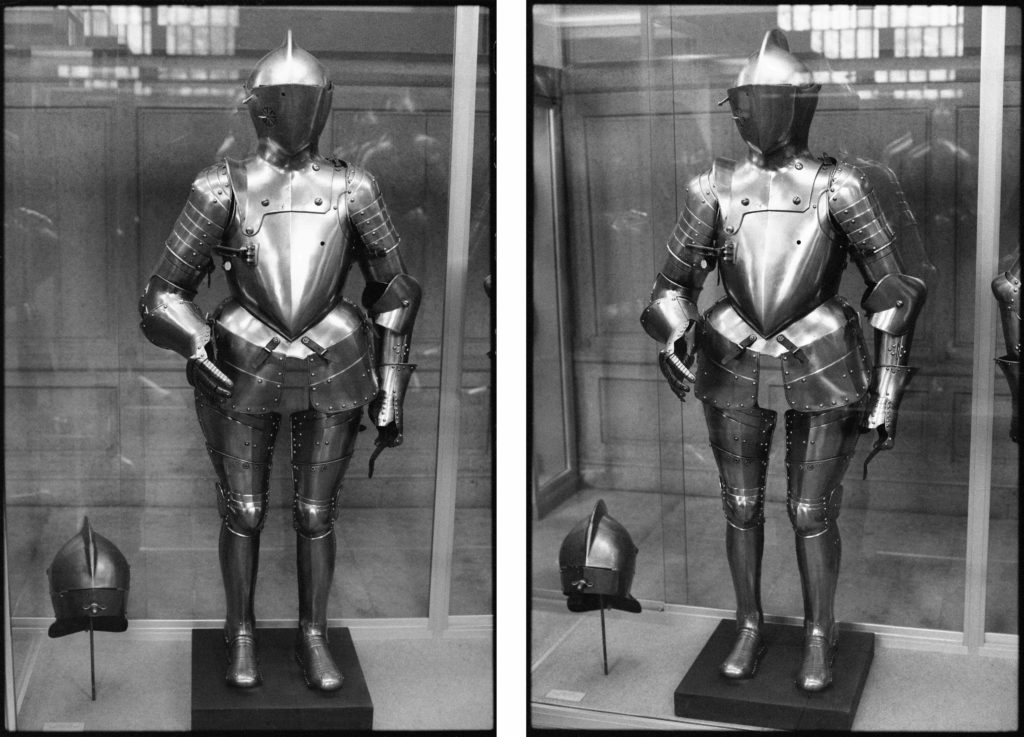

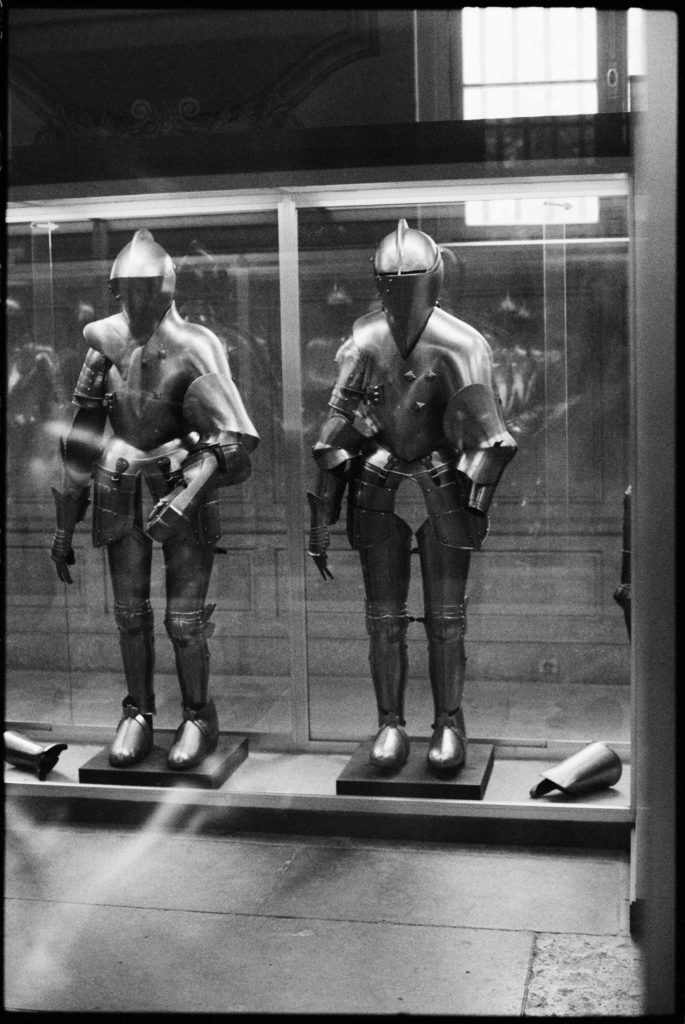

The five works in Zoe Leonard’s exhibition “Display,” at Maxwell Graham, showcase suits of armor installed at the Musée de l’Armée in Paris and the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts. Each work is double dated, its original negative from the 1990s conflated with its fresh print in 2025. While one suit of armor, rather modest in design, presents an ancient cuirass adorned with abs and studded nipples — more of a second skin than anything — the other photographs feature bulbous, metal-plated carapaces that decorated (and abstracted) the bodies of medieval knights.

If suits of armor spark archetypal, even storybook visions of patriarchal power, in Leonard’s photographs their display reveals a betrayed machismo. Stripped from soldiers’ bodies, the armor now stands hollow — once instruments of masculine subjectivation, they are transformed by their respective institution into stuffy objects of historical intrigue and aesthetic delectation. In Display I (1991/2025), parts of the suits even seem to have fallen off, the warring knight suddenly closer to a Bellmeresque doll. Holes dotting the crotch of each ensemble — suggesting for the viewer a pattern of unmissable castrations — push the gendered dimension of Leonard’s cutting, critical gaze still further. Nevertheless, her feminist regard of these suits of armor does not suggest that our phallocentric order has withered away altogether, but instead foregrounds how its maintenance depends on carefully staged visual spectacles. Focused as they are on a particular epoch in the fashioning of masculine virility — but reminiscent, for instance, of the sleek, mechanomorphic bodies splayed across fascist posters from Mussolini-era Italy — Leonard’s photographs remind us that items like armor and the museums that show them produce gender and its hierarchies as part of a carefully choreographed aesthetic regime, one that might be, and so often has been, differently configured by others.

As with the other museological works made by Leonard in the early 1990s, however, in this series the artist’s focus does not strictly rest on the collected objects themselves. Rather, through oblique perspectival shifts onto the environment containing and contextualizing the armor, Leonard’s work accounts for the practice of collection itself (suits of armor in fact lend themselves to this sort of self-reflexive inquiry, their gleaming surfaces already performing the work of reflecting, incorporating, or implicating the surrounding environment). In the four works taken in Paris, Display I, III, IV (all 1991/2025) and IX (1994/2025), for instance, the hardened metal edges of the ribbing running up and down the glass vitrines echo the sharp contours lining the perimeter and internal paneling of the armor within. Leonard’s visual rhyming here suggests a structural relation between work and frame in which the museum is not only a neutral repository of military history but a mechanism of state violence all its own. Her emphasis on the armor’s array of externalities is most poetically captured through the panoply of reflections bouncing off the various sides of the vitrine in each image, which place the suits in proximity with the room at large through a relay of parallax views. In Display I in particular, the two suits of armor on display become refracted into a veritable army of blurry clones, with one string of phantom reflections extending back into space and disappearing into, or invading, the back wall.

This fastidious consideration of the aesthetic container is a familiar tactic of postmodern practice and has positioned Leonard within the historicization of conceptual art’s more politicized idioms, namely institutional critique. What gives this exhibition its urgency, however, is not its exhumation of a critical vocabulary from the 1990s (and before) but rather its acute relationship to the present. In addition to Leonard’s strategy of double dating the photographs, our sense of the works’ stretched temporality is aided by the internal black borders in each image that mimic the litany of horizontal containers defining the vitrines, the black rubber lining its hardware, the molding on the walls, and the pedestals; this play with parallel structuration of scene and image bringing Leonard’s encounter with these suits of armor into tight proximity with her audience’s experience thirty years on.

And of course, the questions that immediately arise during the viewing experience, concerning museums, militarism, and gender, remain terrifyingly relevant. More so than medieval knights, it is the cartographies of violence that activists have furnished in regard to arts and culture organizations’ ties to Israel’s genocidal campaign in Gaza, or the rapid acceleration of ICE’s Gestapo-style abductions, or the securitization of college campuses that more immediately come to mind when walking through Leonard’s show of armored combatants. Pivotally, then, the suits of armor do not merely function as readymade vessels for the artist’s critical position, ciphers for her various thematic through lines that become condensed through some ecstatic centripetal force. These photographs instead operate centrifugally, their pulsating warnings about the culture industry’s barbaric contingencies extending outward, landing here, there, and everywhere.