When Katherine Bradford stopped by Anne Buckwalter’s studio in Maine earlier this summer, Buckwalter was in the middle of finishing a new series of paintings. The two artists quickly fell into an easy conversation about bodies and the ways intimacy finds its way into art. They compared notes on growing up around purity culture, painting figures without faces or genitals, and how eroticism can be both radical and ordinary at the same time. Their talk moved the way their paintings do — back and forth between humor and seriousness, with a lot of curiosity in between. At one point Bradford teased Buckwalter about hiding erotic details in plain sight; later Buckwalter asked Bradford is she thought her own figures had secret erotic lives. Both painters have new shows opening in New York this fall — Buckwalter’s “Lover’s Knot” at Uffner & Liu and Bradford’s latest work at CANADA — but here, in the studio, the conversation was less about milestones and more about the shared joys and risks of making art.

Katherine Bradford: I’m sitting in your studio in Maine, surrounded by your new paintings that are going to New York for your September show. I’ve just seen your beautiful exhibition at the Farnsworth Museum in Maine, and what I’m noticing is that you’ve taken some new steps with this work. I was hoping we could talk about that.

Anne Buckwalter: Sure. Some of the dishes and furniture in this new body of work have erotic narratives painted on them, and that’s a new direction for me.

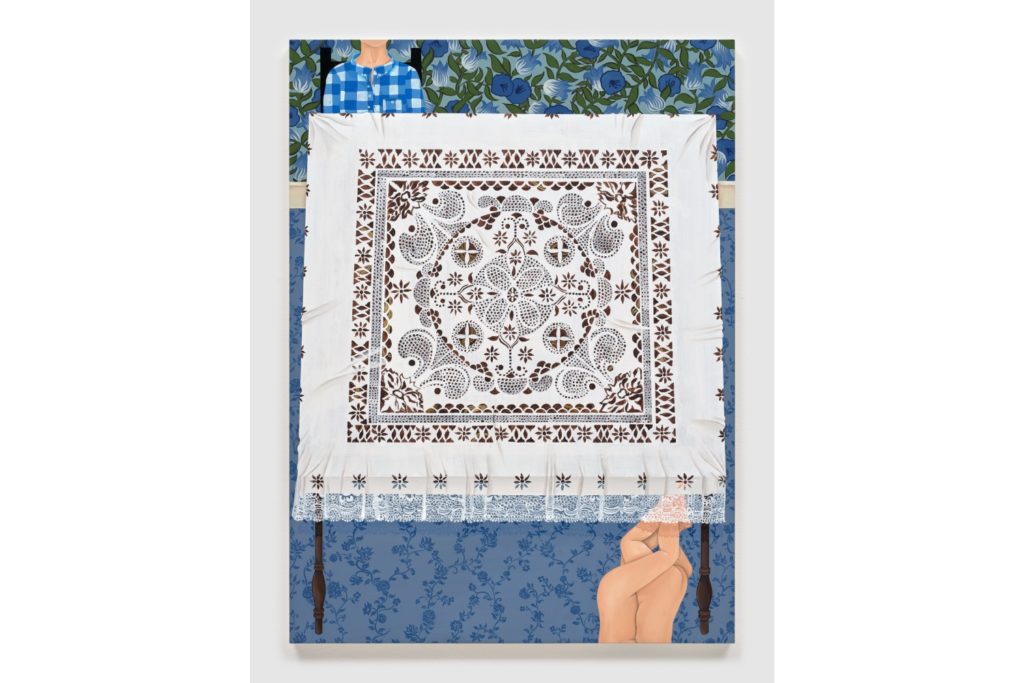

KB: In the past, the erotic components of your paintings were, as you say, hidden in plain sight — you had to look for them, and you were surprised when you found them. But in this new body of work, you foreground them more. Right here, there’s a painting of two young women with no clothes on — that’s very new. I’m looking at a table with a very detailed, meticulously painted tablecloth, and clearly under the table are two females entwined. It’s such a contrast.

AB: I have often painted zoomed-out rooms that showed everything, with small erotic details tucked in — a sex toy, or a figure in a mirror. Lately, I’ve been changing up the scale. These feel more like still lives set in interior spaces, and because I scaled up the size of the objects, it made sense to make the bodies bigger too. They’ve become larger focal points.

KB: You make it sound so innocent.

AB: [Laughs] Maybe — but I’m also just increasingly interested in sex as an intellectual subject.

KB: I think you’re more confident as an artist.

AB: Part of my decision to foreground sex comes from the political climate too. Experiencing joy in the body feels radical right now, give how much repression that we’re seeing.

KB: In art history, women’s bodies have always been present, but I think it means something very different when women paint themselves.

AB: It means something else for a woman to paint her own naked body than for a man to paint the female nude.

KB: And in your case, those bodies are often with another body.

AB: I think of them all as me – self-portraits. I like showing interaction between versions of myself.

KB: I’ve read that, because you grew up in an Amish-adjacent community, you were drawn to the design and style of those Amish Pennsylvania Dutch rooms. At one point you imagined, “What if my belongings were in these spaces?” Is that how the sex toys got on the floor?

AB: Yes. My upbringing was very conservative, especially around sex. I grew up in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, in the 1990s. I was raised in the church. Sex was to be saved for marriage, between a man and a woman. It was purity culture, and I got the abstinence-only education that was so popular at the time.

KB: I think it’s still popular.

AB: For sure. When I moved away from my hometown and started thinking about sex more expansively, I wanted to reconcile my adult self with my childhood self, to bring these two worlds together. For a long time, I struggled with how I was raised, but eventually I realized it’s possible to feel struggle and affection for it at once.

KB: So your work is an homage to the visual world that you were surrounded by and that you admired, but you think there was more to life than this.

AB: That’s a beautiful way to put it. I’m curious whether you think about your own figures as having erotic lives. And I ask that question because, to me, many of your paintings feel quite ecstatic.

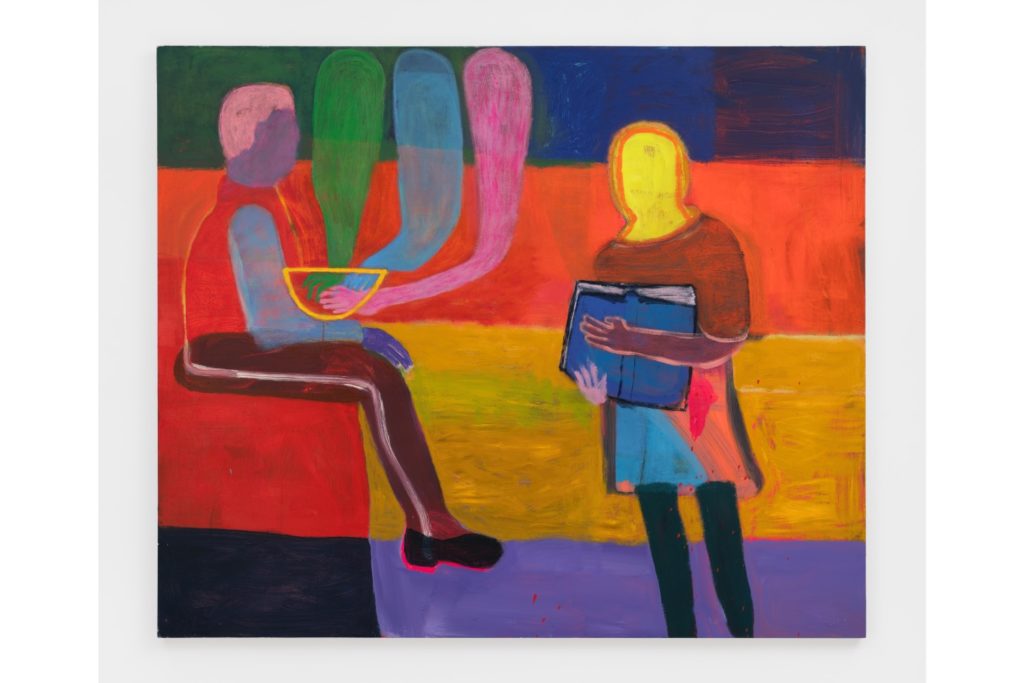

KB: I love hearing that. Often when I’m painting a figure, I stop before I get to the genitals. I might put them in a bathing suit. And I usually avoid painting eyes, noses, and mouths – then faces dominate too much. I come out of abstraction, so I’m interested in shapes. That sounds kind of nerdy, but it’s true. What I do is to make my figures appear vulnerable and awkward. That “in-between” emotional state is what I find compelling. Marsden Hartley did that – his figure are so awkward you want to hug them.

AB: Even without faces or genitals, your figures have incredible vulnerability. I feel the same way about faces: a single expression can set the whole emotional tone, and if it’s not right, the whole painting can feel off.

KB: But someone like Alice Neel was able to capture a face so distinctly that it could be the center of the painting.

AB: Yeah. The question I asked you about whether or not your figures have erotic lives – I am thinking specifically about the erotic in terms of how Audre Lorde defined it, which is as a resource that comes from deep feeling or intuition, and it’s very tied to emotion. I see that in your work because I feel like your paintings are quite emotional, and they often make me emotional. Oftentimes the way you paint skin is not the pinks and blues and browns of flesh tones. Your figures glow and have a neon kind of quality to them. Is there a part of that ambiguity where you want people to see themselves in your work?

KB: One reason I avoid naturalistic skin tones is because that would force me to choose a race, which is another huge topic in itself. Having my figures red, yellow, blue, or purple is my way of saying everyone’s welcome.

AB: Another artist whose sense of color I love is Sarah McEneaney.

KB: Yes, I do too. She also painted realistically her domestic spaces – and herself.

AB: I’ve seen her nude in her paintings.

KB: I have one where she’s in a bathtub. But in your work, a naked body with another naked body — that’s far out.

AB: Do you think it’s shocking?

KB: Yes. But contemporary art is full of shocks.

AB: To me, two bodies touching doesn’t feel shocking — it’s simply part of being human. But I understand why you’d use that word, because culturally we’ve sensationalized sex and stripped it from its ordinary context.

KB: You’re inviting us into the rooms, and the naked bodies caressing each other are private stories within them. That’s wonderful because we want our art to move the viewer very strongly — shocking in the sense of being surprising. Discovering and being thrown off little, which is all good. I think you’ll be rewarded for it.

AB: I think it’s rewarding for me to make these paintings. It feels cathartic in a lot of ways, and that’s a reward in its own form.

KB: When I look at your work, I also sense a coded nature – you insert certain things that don’t always reveal their meaning. When I took history of art classes there was always a discussion around the iconography. It reminds me how in Vermeer everything has a significance.

AB: I don’t think everything means something, but I think there is a sort of mythology building. I relate to the word iconography for sure; there are certain symbols that I’ll repeat.

KB: Vaginal pears, definitely. And in this beautiful big tabletop painting, there are plates of Wedgewood china — and on them, you’ve painted a naked couple having sex.

AB: [Laughs] I spent time at the Victoria and Albert Museum during a recent residency in London. On the fourth floor, they have an amazing collection of ceramics, glass, and furniture. They had a lot of these Wedgwood-style plates and dishes that had narrative motifs happening in the center of the plate, related to English royalty, or sometimes little cherubs, figures prancing around in the forest. You see similar motifs in Pennsylvania Dutch furniture. I thought: If these kinds of narratives can be elevated onto objects we live with every day, why not erotic ones? So I started embedding them into the paintings.

KB: And you’ve succeeded without losing the look of Wedgwood.

AB: Working with that blue helps.

KB: Wedgwood blue! What’s the title of this painting?

AB: It’s called Lazy Susan, because that circle in the middle is a Lazy Susan, which has nothing on it. I just like the wood, the two different ways of painting wood. The table was painted with a transparent wash of acrylic gouache, and then the Lazy Susan on top was painted more opaquely. I liked those two textures together.

KB: You’re also very good with your puns. You named your show at the Farnsworth Museum “Manors,” spelled like the house manor. But we soon learned that what you’re also interested in is good and bad “manners.” I thought that was very witty.

AB: I do like wordplay.

KB: And this show is called “Lover’s Knot.”

AB: Yes, after a quilt pattern, but also how lovers become knotted together.