Attilia Fattori Franchini: The exhibition at Istituto Svizzero in Milan, curated by Gioia Dal Molin, brings your work into a direct dialogue while offering synergic possibilities. I would be happy to start with the exhibition title, “NYX.” How was it formulated, and what does it hint at?

Maude Léonard-Contant: “NYX” somehow came out of nowhere, and I mean this in a good way. I stumbled across a series of books by the poet Anne Carson on my shelf and remembered Nox (2010), a notebook of memories she wrote after the passing of her brother, which had been on my reading list for a long time. The figure of Nox, the redoubtable goddess of the night, struck a chord with us. From Nox, we moved to its Greek counterpart, Nyx, which I like because when I say it out loud I hear “nothing,” the way my children mispronounce nichts in German.

For a less frivolous reason, I relate to Nyx because the works I have been developing focus on death, the possibility of healing, and ominous destinies. Moreover, Nyx is an idea that lives on the edge of the world, and these works also tell of faraway places. They are even haunted by them.

Monia Ben Hamouda: It’s a title that, at first glance, may seem very dry. Nevertheless, I think it’s extremely connected with our — my, Maude’s, and Gioia’s — interest in language and with the idea that the idioms we speak have been given to us by others, by the past — perhaps by a goddess — and how we use these languages and restitute them to others. We had numerous ideas for titles for the exhibition and discussed many possibilities. The final title came from Maude’s suggestion, and it immediately resonated with me and Gioia for disparate reasons. I found it interesting, for example, how we needed to give a proper noun to the project, more than a narrative, conceptual, or explanatory title, because it shapes the idea of giving to the exhibition its own path and a future beside us three. Giving a name is an act of love and faith, like expressing a wish for others. Human names are the hub of our dreams for the future, so naming is a very powerful act. I guess the act of naming this show could be seen as the merging of our wishes and our desires.

Gioia Dal Molin: Maude says that “NYX” came out of nowhere, and Monia writes that finding and giving a name is also an act of love. I can only agree with these thoughts and add that, according to Greek mythology, Nyx was also born out of chaos. This idea attracts me, and I am interested in this personification of the night and the process of creation that revolves around her. I don’t want to draw parallels with artistic work processes, but I like the fact that Nyx combines abysses and creation. This is also related to Maude and Monia’s practice: both artists work with words and language as images and with the depictability of language in the broadest sense. We decided on the Greek version of the name, Nyx, instead of the Latin nox, and wrote it in capital letters in our communication: “NYX.” For me, beyond its mythological and cultural meaning, the word also becomes a written image, an image that language contains within itself.

AFF: I’d like to know how you worked toward the construction of this exhibition, what your inspirations were, and how your dialogue evolved.

MLC: The dialogue began with a question from Monia: What’s your color palette at the moment? Her question was very refreshing and timely, as I was newly infatuated with pink medicinal clay. Later in the process, we exchanged texts, which brought forth themes for the exhibition. In my case, among others: shedding skin, death, tenderness, and the sometimes overwhelming power of more-than-humans.

A sense of fearlessness presided over the development of the project, and as the exchanges unfolded, a space of trust also opened up, for which I am grateful. Even if it is not often acknowledged as such, working atmospheres inform the making of exhibitions, even if subtly. As a result, our works might contaminate themselves. Monia will be coming into the room from time to time, and she has my permission both to contaminate my installation with her spices and, if she wishes, to use the medicinal clay from which my installation is made to sprinkle the floor, which I will leave at her disposal. We feel very free to allow our two practices to coexist independently and together.

MBH: I wanted to talk to Maude and Gioia about the frustration I have been feeling lately with institutions and the current geopolitical context, and the difficulty in articulating this frustration linguistically and formally. I think a lot of my own and the work we are doing together spurs from the urgency of trying to heal ourselves and our practices from the continuously unfolding brutality we are witnessing daily. I am currently working on a new series specifically focused on this overwhelming feeling of frustration and the impossibility of articulating a language around it.

GDM: The double exhibition held once a year at the Istituto Svizzero in Milan, with an artist from Italy and an artist from Switzerland, is centrally based on the idea of dialogue and exchange. Two artists share the exhibition space, and this alone allows them and their works to dialogue. As a curator, I try to invite artists who I suspect have common interests or themes — and sometimes I know this for a fact. I am less interested in formal similarities than in shared themes or research. In the case of the exhibition “NYX,” I knew that I wanted to work with Monia. Although she lives in Milan, I got to know her work in Zurich in the project space jevouspropose (wonderfully run by Sabina Kohler). I remember how happy that exhibition made me — the smell of the different spices in my nose! — and how happy I was to discover that Monia lives and works in Milan. After a studio visit with her about a year ago, I knew that we were a good “match” in terms of energy and working methods. Monia and I then did some joint research for an artist from Switzerland, an approach that made sense to me and corresponded to the exchange I had created between Monia and myself. I seem to remember that she suggested Maude, and I think she saw the similarities more quickly than I did. I worked with Maude a few years ago in Zurich, and I admire her sensitivity for language and words and how she translates them into wonderful sculptures.

The exhibition grew out of one personal meeting, a few Zoom calls, and many, many emails. We all have a great affinity for written language — I think while writing — so this approach was ideal for all of us. In the last few days, we had another intensive exchange about the fact that the thinking space that the show has created for us is also a “safe space” that is nourished by trust in each other and the courage to want to think and work together. This is such an important experience for me. And now I’m really looking forward to installing the exhibition and the opening.

AFF: Your practices share a strong interest in materials: you use everyday substances that belong to the culinary context, such as spices and salt, but also more natural elements such as sand, ceramics, or wood. How does your material vocabulary form? What narratives does it unlock?

MLC: For some time now, the materials I work with have been charged with symbolic meaning and consciously linked to childhood memories; they are part of my pedigree. There’s often a lot of tenderness involved in assembling and manipulating them; it is not unlike writing love letters or being a proud parent eager to show the world the worth of their offspring: “Look at what this one can do, how robust, how prompt to metamorphosis.” Sometimes the choice of the materials is determined by the texts I write. For example, in 2020 — a year’s worth of writing fiction, like proper foundations — texts led to the use of nine tons of foundry sand to press their fragments into.

On other occasions, a precise desire for a material emerges at the start of a project, around which I articulate a visual syntax through a back-and-forth between materials and texts/language, the latter also becoming a material. Through writing, I can clarify sensations and textures, which allows me to refine my plastic choices: for example, having silk cut by laser rather than by hand following the description of the bark of a specific birch tree; or planning an installation differently after a river in flood has imposed itself as the protagonist of a story, leading me to strand the sculptures rather than displaying them on the floor.

At the end of the process, I often feel like I’m presenting a family, each member of which has an equally valid story to tell — even the smallest porcupine quill or poppy petal. For “NYX,” lots of materials were involved and the process felt like stirring a big soup; a regenerative mixture, but one not devoid of toxins.

MBH: We have some common points regarding materiality, but we also have some divergent ways of thinking about them through our sculptural work. My relationship with materials has always been allegorical and symbolic, in the most possible religious sense. I began my career working with materials that carry a denotative strength, a characteristic I was trying to deepen or manipulate — such as pork meat, which for my Muslim context has a specific valence. I’m interested in how certain materials hold a strong power, and what mechanism transforms them from matter to symbol. Building on this, I also tried to work a lot on the ceremonial and healing aspect of certain spices, and how in my work there is often an olfactory palette, sometimes very sweet, sometimes extremely violent. So, the work wasn’t just a visual phenomenon, but a physical one, which could enter, change, and disrupt the visitor’s body: from the power of tears that came from a strong smell of chili peppers to the sneezing of paprika to the sweetness of turmeric. My work generates a physical reaction in the viewer that is impossible to suppress; it’s very intense, and prolonged, and therefore it has the power to change whoever encounters it directly. It’s interesting to me that the work has the power to heal or curse someone: through this aspect, I see a religious and ceremonial appeal in my work.

Every exhibition is like a ceremony for me. In recent years, however, my practice has changed from this religious connotation; many of the elements and materials that I use are veering towards a strong political direction. I often wonder how my gestures can recall certain activist gestures and support collective struggles. How often these acts turn violent towards the artworks, and how a particular gesturality already inherent in my work evokes the gestures of activists, strikingly akin to the stereotypical portrayal of people of the Muslim faith as intrinsically violent and evil, and constantly associated with destruction.

AFF: I’d be curious to learn what materials were involved in this show and if Maude’s work is this time connected to specific texts she wrote on the occasion of the exhibition, and how these texts are articulated through the work.

MLC: The best way to start answering your question is to list the materials chosen, which, now that the work is finished and they’ve all found their place, feels like reciting a Thanksgiving address or a eulogy:

broad-leaf cattail cob

glazed and unglazed stoneware

pleated silk

wild silk

silkworm cocoons

healing clay

galvanized sheet metal

fluorite

selenite (or moonstone)

peacock feathers

petroleum jelly

pink quartz

poppy petals

rooster tail feathers

white horsehair

black horsehair

aluminum mesh

Most of these materials are directly linked to three texts that were written when I started working on these pieces and that gave shape to the exhibition. The only material chosen at the outset was medicinal clay, or healing clay according to DeepL; I use this somewhat literal translation on purpose since I find it more accurate. The other materials emerged while writing; they refer to places where the action of the texts takes place. For example, the galvanized sheet metal that makes the letter-sculptures scattered on the floor recalls the tin roof of the sheepfold where my sister unwittingly murdered a chicken; the healing clay summons the clay found in patches at the bottom of the bed and on the banks of the river that helped my neighbor Laval commit suicide, as well as the fluorite and moonstone of a sculpture that echo the crystals he used to ingest to increase his energy field.

Some fragments of these texts are found in the titles of the works. This is the case with giving her utmost at dressing the dead chicken (2024), whose translation from French into English incidentally dictated the choice of delicate silk, and a work of plumasserie, because the French parer (trim) became “dressing” and made me want to play on the multiple meanings of the word, as in “adorn” or “wear” or “dressing up” – in putting on one’s best or putting on one last suit of finery.

Other text fragments can also be found in the exhibition: on the floor, made up of healing clay sprinkled through stencils, forming small piles like earthworm droppings – these are all words to be deciphered. Further out, small, plump, pearly, ceramic letters resembling worms or crustaceans are thrown like dice to utter the sentence “unfathomable volumes of water.”

AFF: I would like to reflect on the specific works and installations that you have prepared for the show, their inspirations, and, if any, their challenges.

MLC: All the works were created for the exhibition, continuing a cycle fueled by grief, the loss of more-than-humans, and my tenderness towards them. Specifically, for Istituto Svizzero, alongside my recent crush for pink healing clay, I aimed to evoke beneficial deaths, those that could bring healing or a promise of renewal. I fear this intention might have gotten a bit lost in the process.

An emblematic absence in the show reflects this possibly missed rendezvous with hope and healing. In connection to the third text I wrote, I had intended to include candied Buddha’s hands — Citrus medica — in the show due to their resemblance to chicken feet and the alchemical quality of the confectionery process: through the sugar, the preserved fruits gain transparency and quasi-immortality. I suppose this work also stems from my childhood craving for candied fruit, which, due to my upbringing by granola parents who were opposed to sugar, turned into forbidden fruit. Eating them was like eating jewels or precious stones. Including these Buddha hands in the show also felt like fulfilling a fantasy, particularly since they were almost impossible to find at that time of year. Eventually, I found some at an exorbitant price, along with a confectioner willing to attempt the process. Unfortunately, at the end of the week-long process, the hands were burnt in the syrup, resulting in a total loss. Despite their macabre appearance — they transition from a translucent bright yellow to an ominous black — I decided to include the charred fruits in the show. But fate struck again: the fruits were carelessly thrown away! As I write these lines, I realize that I will never have the sensory experience of these annihilated fruits, as everything occurred through photos, online orders, and email exchanges.

I tell this story because even though my relief at their disappearance now matches my initial desire to display them, they still linger over the exhibition. The Buddha hands greatly trouble me; they operate on a symbolic level, their absence summoning other nightmarish visions. They are the phantom limbs of the works I exhibit at Istituto Svizzero.

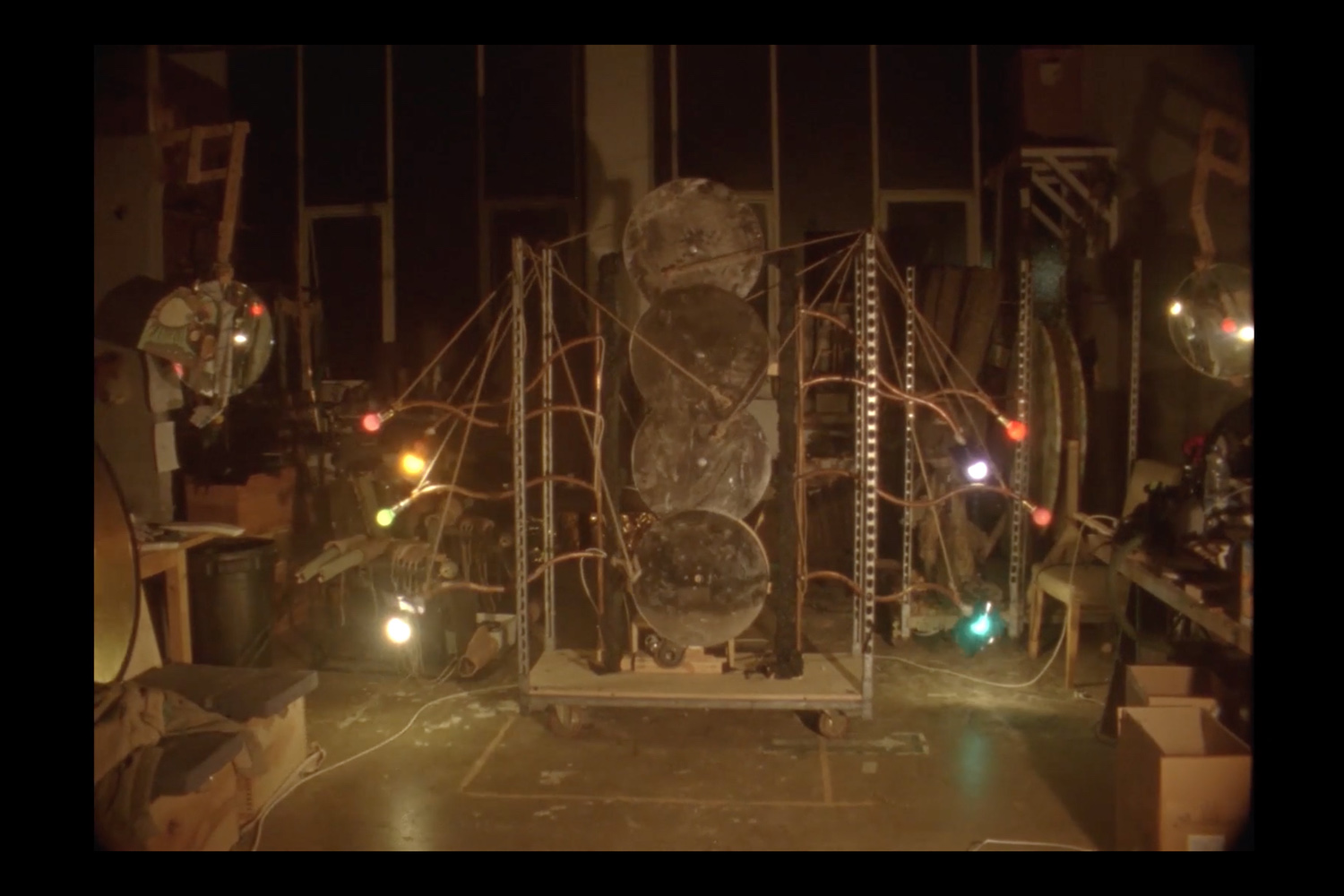

MBH: I’m working on a prototype of what I hope I’ll be able to transform into a new long series of sculptures. The impetus to work on this piece comes from my desire to formalize a piece that could contain but also destroy my own practice, like an implosion, a kind of theorization of the collapse of my work. I see this sculpture as a radicalization of what have always been my practice’s central themes and junctures, as if to invalidate and reinforce them simultaneously.

It’s a very dry piece, working on the idea of fragmentation, collapse, anger, sterilization of meanings, and the concept of ruins as a politicized space. Eventually, it attempts to resonate with notions of flattening consciousness and moral apathy as vivid, alive structures of human society.

Writer Khadija Muhaisen Dajani has been an important inspiration for me –– her words describe my work Burial of all meanings (2024) perfectly, which is now on display in the show: “There is no English equivalent to the Arabic word qaher قهر. The dictionary says ‘anger’ but it’s not. It is when you take anger, place it on a low fire, add injustice, oppression, racism, dehumanization to it, and leave it to cook slowly for a century. And then you try to say it but no one hears you. So it sits in your heart. And settles in your cells. And it becomes your genetic imprint. And then moves through generations. And one day, you find yourself unable to breathe. It washes over you and demands to break out of you. You weep. And the cycle repeats1.”

GDM: I always think of the exhibition projects — especially in Milan, where we have an audience that is usually very well-informed about contemporary art — as a place where artists can try things out. My aim is to create a real and imaginary space in which works can be shown that are perhaps still in a fragile state of growth, works whose energy and aura only become clear during the exhibition, works that can take on a variety of possible forms in dialogue with the public. Especially in the context of the double exhibition, where I only really see how the works enter a dialogue with each other in the exhibition space itself, and how something new emerges in this exchange.