Sheepish admission: despite living in an adjacent country, I’d never attended the Biennale di Venezia before, even though it’s a fulcrum of the global art world — I know, I know. In the lead-up to the trip, I was already feeling intimidated by the scope of the event and reeling based on the sheer number of press emails I was receiving. This year there are eighty-eight participating countries, four of which are present for the first time: the Republic of Benin, Ethiopia, the United Republic of Tanzania, and the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste. I was determined to absorb as much as I could, although by the end of each day I wished to have a new pair of feet the way you would otherwise put on a new pair of socks.

For this sixtieth edition, the Biennale’s title draws from a series of works made by the Paris- and Palermo-based collective Claire Fontaine: “Foreigners Everywhere.” (This in turn comes from a Turin collective with an anti-racism and anti-xenophobia agenda from about twenty years ago: Stranieri Ovunque.) The namesake work — suspended in the Gaggiandre shipyards — consists of multihued neon words for “Foreigners Everywhere” in fifty-three languages, flaring against the glimmering waters below. As someone whose accent is remarked upon daily thanks to living in her non-native country, I relate to the feeling of being relegated to a kind of unrelenting foreignness.

Roberto Cicutto, president of La Biennale di Venezia, wrote in a statement: “La Biennale’s international nature makes it a privileged vantage point from which to observe the state of the world through the transformation and evolution of the arts.” Indeed, that state of the world is seething with malaise, restlessness, and alarm — but also an urgency to reinstate parity for those who have been overlooked, and that restitution feels unfeigned and meaningful. An ambitious project like the Biennale refuses to let us tamp down our anxiety around what is churning in the world, in the way we usually do simply to function day to day. The pavilions help us conceptualize, concretize, illustrate, and metabolize global realities using a striking and exhaustive scope.

While making my way to my hotel and attempting to determine whether the blue dot on Google Maps was pranking me or not (half the time it seemed to be indicating I was in a canal), I happened upon the Nigerian Pavilion, designated with neon-green signage in front of the sixteenth-century Palazzo Canal. “Nigeria Imaginary” proposes a Mbari-style club (center for cultural activity) as its setting, with eight artists making site-specific works. There is more of an optimism here than I would find elsewhere: legacies of the colonial past are transformed into a hopeful sense of the future.

On the ground floor, a radio tower designed by Precious Okoyomon, Pre – Sky / Emit Light: Yes Like That (2024), registers changes in the atmosphere and converts those into refreshed audio feeds (bells and electronic synthesizers), alternatively broadcasting words by Nigerian poets, artists, and writers. Upstairs, in a nod to the tradition of Venetian ceiling painting, a vibrantly colored work by Tunji Adeniyi-Jones unspools overhead, while in another room, elegant works by Toyin Ojih Odutola recreate an imagined story for her grandmother and an elusive, perhaps impossible, collective cultural history. In an accompanying essay, curator Aindrea Emelife writes: “In Lacanian theory, The Imaginary is not just fanciful or fictional, it is essential to our ordinary life and functions. Lacan identifies the imaginary as necessary fiction and key to allowing for someone to engage with their surroundings. The absence of these fictions frames the ‘Real’ as unbearable, unstructured, and inharmonious. The Imaginary is made up of illusions that combine to form vision and structure, and to bolster harmony and unity between peoples and places.” Amen, Lacan. We need our illusions to make it through.

Post-hotel, I made my way to the Giardini and entered the unfathomably sprawling “Foreigners Everywhere” group exhibition overseen by this year’s Biennale curator, Adriano Pedrosa. The theme is consequential, as the number of forcibly displaced people is ever-increasing in record numbers. In his statement, Pedrosa emphasizes: “The Biennale Arte 2024’s primary focus is thus artists who are themselves foreigners, immigrants, expatriates, diasporic, émigrés, exiled, or refugees — particularly those who have moved between the Global South and the Global North.” Foreigners everywhere in Venice, on a pragmatic level, may feel like gluts of hapless tourists walking too slowly while you’re desperately trying to cross a bridge, but Pedrosa speaks to the universality of human movement — wanted or not — of different lineages, expressed as either a burden and a privilege (or a mix) depending on how that trajectory unfolds.

There are a great number of queer artists and queer-centered works on view in the exhibition, which was invigorating to see. A sample of these, across the Giardini and Arsenale, included paintings by New York-based Louis Fratino, depicting “the male body and domestic spaces [that] capture the intimacy and tenderness found within everyday queer life”; a huge multi-panel canvas embroidered with lesbian orgies by Mexico City-based Frieda Toranzo Jaeger titled Rage Is a Machine in Times of Senselessness (2024); Beirut-based Omar Mismar’s mythologically inspired mosaics in which one depicts two men kissing (Two Unidentified Lovers in a Mirror, 2023); Johannesburg-based ’s photographic series spotlighting queer figures exuding pride and sporting fantastic style despite being in safe houses in Lagos; Buenos Aires-based artist La Chola Poblete’s paintings in which there are hybrid male/female bodies and silhouettes holding up signs with slogans like BASTA DE VIOLENCIA CISEXISTA; and Bangalore-based Aravani Art Project’s gigantic vivid mural of trans bodies, Diaspore (2024), within a bright panorama of green leaves and blue and red flowers.

When I exited “Foreigners Everywhere,” there was an obvious brouhaha of chanting and I thought, “Oh, there must be an early performance nearby.” But it was actually a protest in front of the Israeli Pavilion, with red fliers distributed and scattered afoot (“DEATH IN VENICE: NO TO THE GENOCIDE PAVILION”). The pavilion was left locked and closed to the public by artist Ruth Patir, as a way to criticize the Israeli government and its refusal of a ceasefire; on her website, Patir writes: “The decision by the artist and curators is not to cancel themselves nor the exhibition; rather, they choose to take a stance in solidarity with the families of the hostages and the large community in Israel who is calling for change.” Passersby pressed up against the glass windows to glimpse the film, Motherland (2024), centered on fertility statues, playing inside, as two camouflage-outfitted Italian soldiers sternly stood watch. However, the artist was seen giving private tours of the show, seemingly in contradiction of her statement.

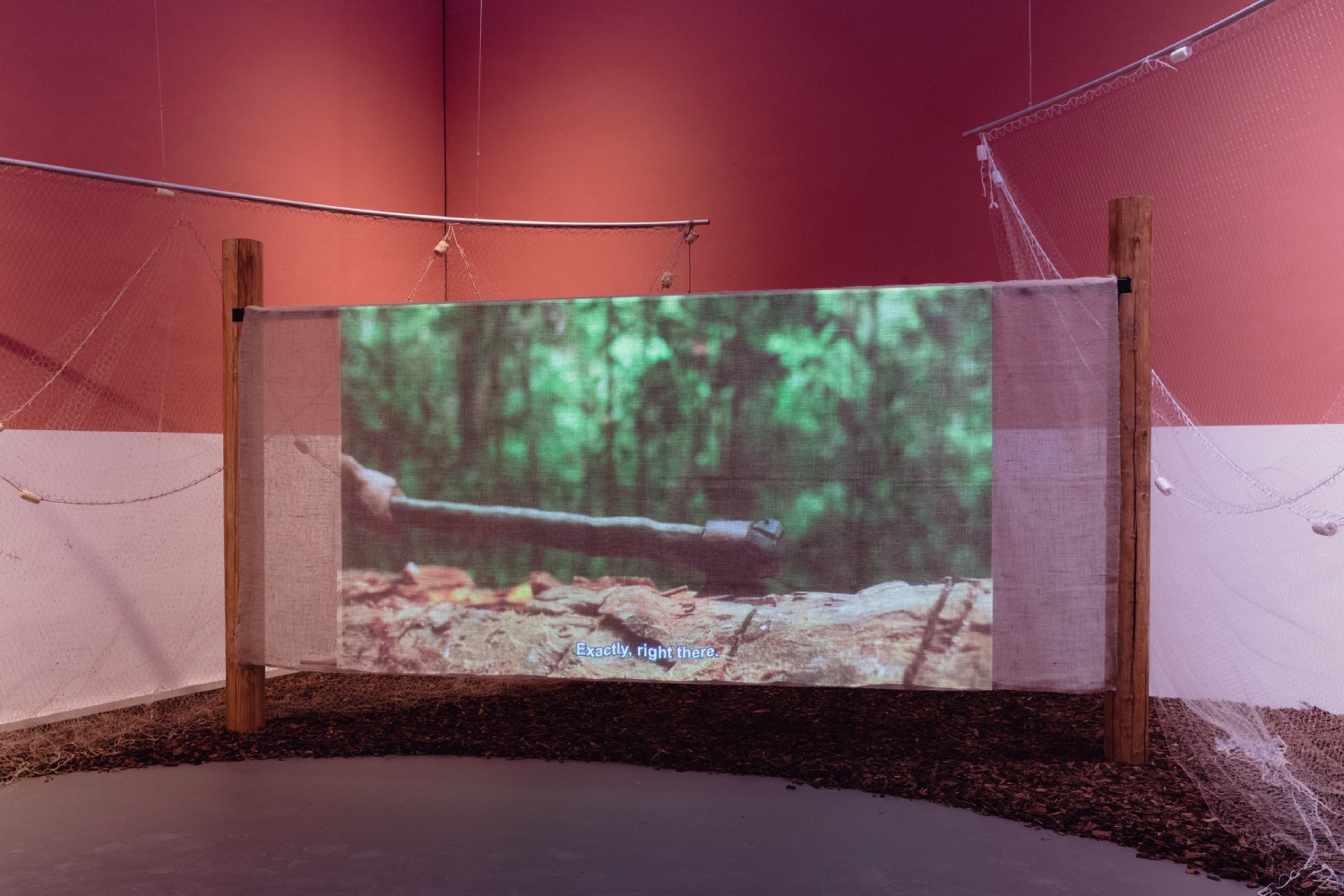

More tranquilly, Brazil’s Pavilion (rechristened the Hãhãwpuá Pavilion this year, reappointing it to its original indigenous roots) featured feather mantles and tarrafa netting in a conception spearheaded by Glicéria Tupinambá (with the Tupinambá Community of Serra do Padeiro and Olivença, in Bahia, Olinda Tupinambá, and Ziel Karapotó). The exhibition highlights the artistic production of Brazil’s buoyant native peoples, while spotlighting the ugliness of colonization and marginalization. Indigenous identity was celebrated at the Australia Pavilion too in Archie Moore’s exhibition “kith and kin”; he was awarded the Golden Lion for Best National Participation in honor of an all-embracing 65,000-year First Nations family tree, hand-drawn in chalk.

Elsewhere, the unremitting weight of diaspora was expressed at the French Pavilion, which was conceived by Franco-Caribbean Julien Creuzet. Here, “stories of the Atlantic intertwine with those of the Mediterranean and link a multitude of mythologies,” as inspired by the artist’s roots—he chose to unveil his project to the press while in Martinique, addressing the reality of being “an ‘overseas’ citizen” as an islander. The colorful installation of large textile mobiles, suspended from the ceiling, showcased the allure of hanging fibers, while six fluid videos populated with hybrid creatures, aqueous plants, and Parisian lapidaries gently floated through teal waters like ethereal wreckage. Creuzet stated: “Beauty is born of a kind of displacement or of distance, rather than withdrawal into the self.”

At the Swiss Pavilion, the mythology of a place versus the reality of a place becomes something necessary to untangle. Geneva-born, Rio-based Guerreiro do Divino Amor presents the sixth and seventh chapters of the artist’s ongoing Superfictional World Atlas (2005–) saga, a passion project for nearly two decades. In a previous interview, he said the work encompasses “the ideas of empire and galaxy, the war between civilizations with their different social, religious, economic, symbolic, and aesthetic aspects, the different strategies of racial whitening.” As informed by his studies in architecture, classical elements like columns, fountains, and fake marble articulate totems of power. The video Miracle of Helvetia (2022) stages a grand allegory of Switzerland, represented as a “super-fictional” paradise. A corridor leads to the bright kitschy installation Roma Talismano (2024), proposed as a phantasmagorical twin of Roman civilization featuring Brazilian singer Ventura Profana.

Although I hadn’t seen everything in the Giardini — and felt guilty about not being a completist — the next day I trudged over to the Arsenale, where I heard there were no lines. At the Luxembourg Pavilion, curator Joel Valabrega oversaw work by Andrea Mancini and the collective Every Island (Alessandro Cugola, Martina Genovesi, Caterina Malavolti, and Juliane Seehawer); throughout the duration of the Biennale, the pavilion is hosting four guest artists who will present sound performances for an immersive experience. The four are Spanish musician and performer Bella Báguena (self-described as a “trans nonbi lesbian animal”); French transdisciplinary artist Célin Jiang (with a signature decolonial cyberfeminist approach); Ankara-born performance artist Selin Davasse (operating according to research-based performances); and Swedish artist Stina Fors (implementing choreography, performance, drums, and vocals). At the time I visited, Selin Davasse was hopping around the pavilion in a neon-tinged leopard-print skirt, her torso at a 45-degree angle.

Shifting to another corner of the Arsenale/another corner of the world, I checked out one of this year’s newbies: Benin. Its pavilion brings together “nuanced gestures and artistry”: graphical paintings of women in beautiful patterned dresses and headscarves, in various shades of intensely bright blue, by Moufouli Bello, behind which are custom blue-encased books by the likes of historian Adrienne Mayor and Gabonese writer Angèle Rawiri. Across the room, a bay window in steel and verre colonial hangs adjacent to blown-glass musical instruments (the latter were once stored in the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris) by Chloé Quenum, while Romuald Hazoumè’s rounded structure of recycled jerrycans is filled inside with sound and the fragrances of plants. A solid introductory debut that, like the Nigerian Pavilion, proposes an expectant view of African identity.

It seemed like you couldn’t go to the Venice Biennale and not pay homage to the host country, though I was thinking about ignoring that logic because the Italian Pavilion had a very long line. Forty minutes later, it turned out it was one of my least favorite experiences (and not just because, once I was inside, I realized how much space there was despite the queue). As organ music played, curator Luca Cerizza’s opening text about Massimo Bartolini’s proposal to “listen to the other” sounded like a grade school imperative and not at the level of the “Foreigners Everywhere” approach that made identity an indispensable, compelling expression. The text’s concluding note, that the installation is “listening to a multitude… for a multitude of listeners,” felt glib. Symbolically enough, given the heavy scaffolding that invaded the pavilion, there was more work to excavate in terms of concept.

Not liking this pavilion was a confirmation that, by contrast, this was an edition that mostly had lots to say (minus Hungary’s shallow rumination on techno subcultures and Korea’s baffling meditation on scent that was without a notable olfactory presence). The overwhelm I felt after I engaged with many pavilions, like Poland’s onomatopoeia about the sounds of war or Spain’s postcolonial revisit of the pinacotheca, was because there were resonant, critical, pressing things to reckon with as offered by politically engaged artists in their pavilions. Roberto Cicutto’s statement about the Biennale as a “privileged vantage point” was confirmed by my experience: I felt informed in a way that was more fruitful than reading the news, and empowered by the deconstructive ways artists criticize the status quo in order to make it better.