“And Your Flesh Is My Greatest Poem” takes its title from a poem itself. Brought together by curator Mohamed Almusibli, artists Sitara Abuzar Ghaznawi, Isabelle Cornaro, Shahryar Nashat, Dala Nasser, Hana Miletić, and Ser Serpas explore poetic abstraction in ways relevant to their mutual subject of the body and respective mediums. Risen from the materials of these artists’ fevered process, the painted and sculptural exquisite corpse still bears the inevitable scars of ordinary life. To regard the abstracted, artificialised poetics of the body is complicated, so far from ordinary somatic philosophies. Ripe folds, cartilage, fluid discharge, bloating – all assessed by the artists as they test the extent to which the remains of the body are functional, and how corporeality may be legitimised on a conceptual level. In uniting these positions under poetry, Almusibli invites reflections on the deconstructed sensorium.

Isabelle Cornaro’s larger-than-life-size resin pillars show reliefs of bodily and artificial litter (Streams II, 2019), however it is Nasser’s naturally-dyed bed sheet compositions which bear closer resemblance to Heidi Bucher’s seminal latex “skins”, despite not sharing the deep cavities of their object-scars – the largest of her works measuring over three-by-two-and-a-half metres, Al Mina (The Port) (2021) slouches to the ground and is gently frottaged with charcoal, ash, salt, and other natural pigments, a subtler archive of the experience of the body of the family among ruins.

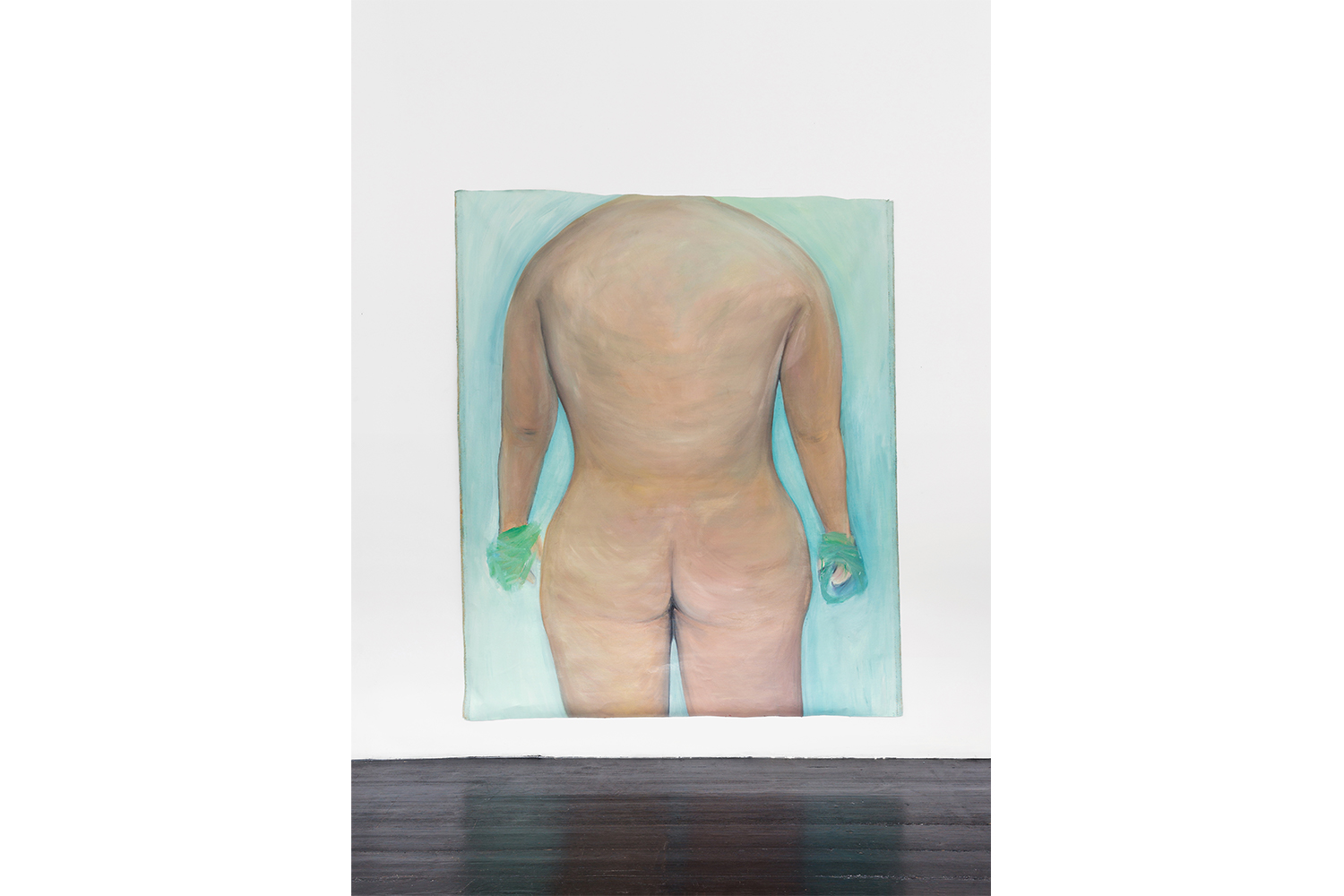

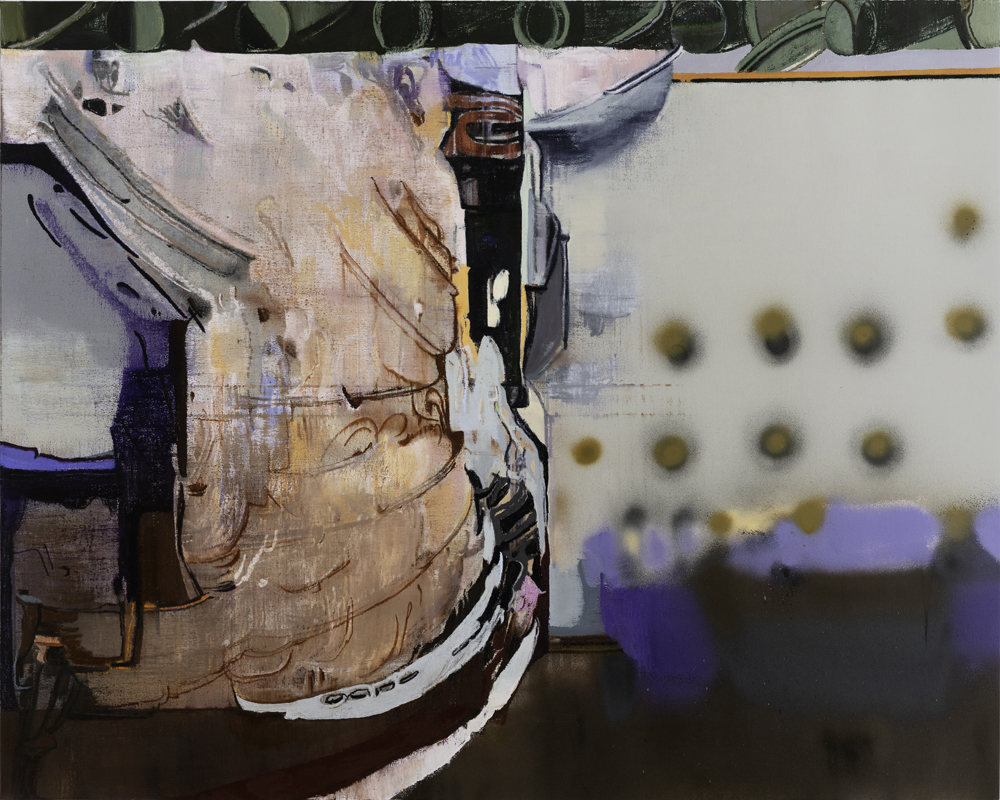

Less elegiac, Ser Serpas’ differently sized portraits on unstretched canvas reveal large swathes of skin belonging to anonymized plastic surgery patients (but not their faces) as she tracks the progress of various surgeries via before and after photos from the website RealSelf. In one untitled work from 2022, the patient looks to be wearing nothing but green latex medical gloves, in another, smaller, work from the same year, the skin around the patient’s abdomen appears red and sickly yellow, tender perhaps, but this is about our greatest clue regarding the opening up of their body.

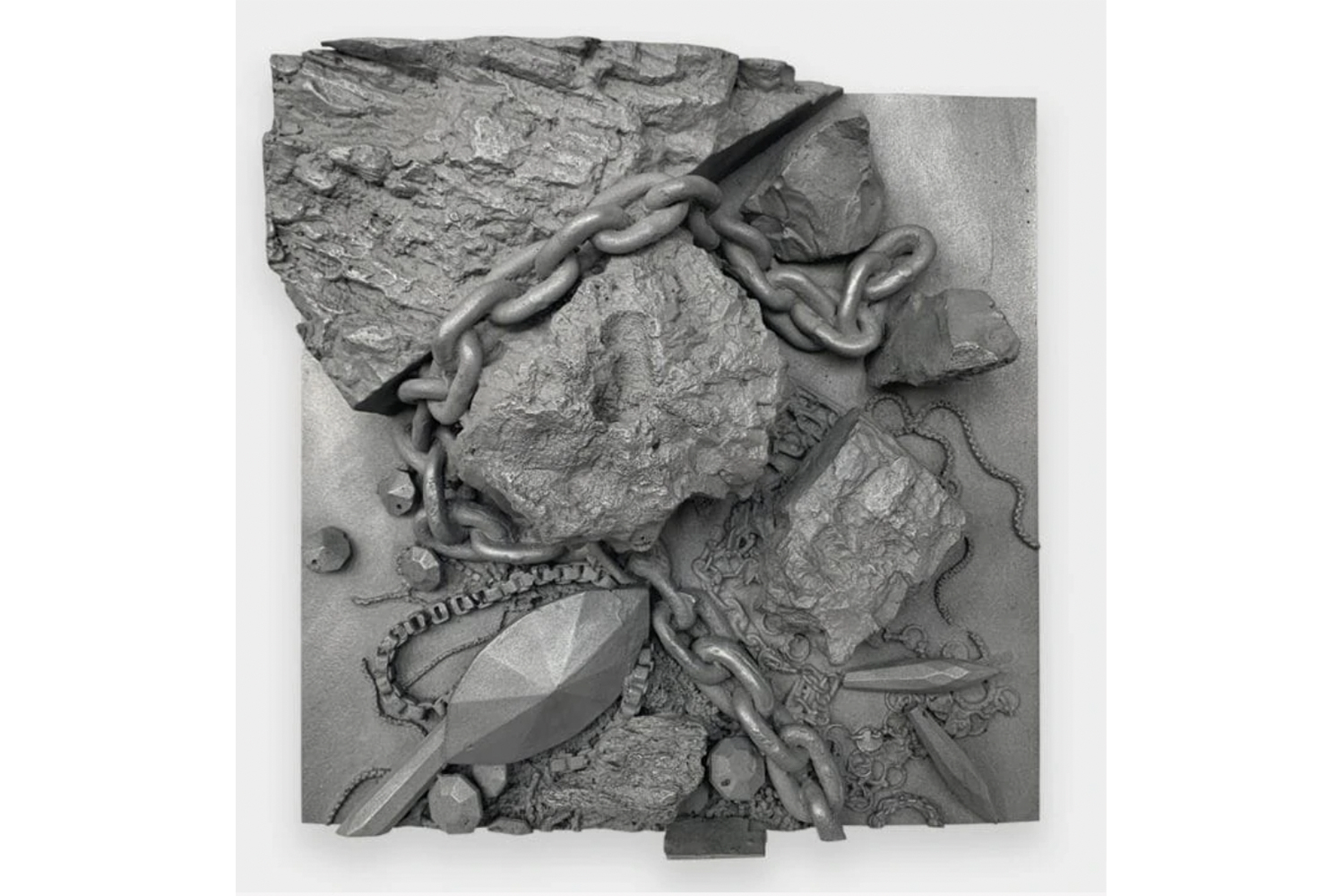

Shahryar Nashat is most explicit in this regard, showing hunks of meat made from resin (Bone-In, 2022), a painting of a landscape of flesh and bones (Boyfriend_10.JPEG, 2022), and an assemblage of see-through vinyl bags filled with his lover’s yellow urine laid out on a foam mattress (Lover_25.JPEG, 2022). Likewise, peeking between the chrome legs of Abuzar Ghaznawi’s bar-stool-bodies (Saint, 2021), we see their guts of roses, mesh, foil, empty cigarette packets and other items endemic to her readymade sculptures.

Par Serpas, only Hana Miletić seems to err on the side of healing its pragmatics, the forms of her hand-woven and automated Materials and Softwares textile sculptures (2019-2021) coming directly from the shape of repairs to damaged and transformed inanimate objects in public space.

The sublime aspect of existing within our own bodies is, of course, the myth of their function and how this myth remains mostly sealed within a hermetic unit, the great instinctive adventure of our lives being to keep this unit intact, or at least avoid damage to it at all costs. To consider any body as a sum of its remains causes a crisis of the real. “Nothing is familiar, not even the shadow of a memory,” writes theorist Julia Kristeva in her seminal psychoanalytic text Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (1980) – the idol of the body feigns romanticism in its attempt to be sincere.