Lene Berg’s “Fra Far,” on view at Bergen Kunsthall, is about a murder, and it is not a spoiler to say that the artist’s father, a journalist, playwright, and director, committed the crime. The show, whose title means from father, is literally full of things from her father, reproduced and printed on textile. Additionally, archival footage is punctuated with commentary, and testimonies are played, many spoken by Lene Berg herself in a detached voice without any pretense of authority.

Berg, a filmmaker by training, is now firmly rooted in the art world. “Fra Far” has been commissioned as part of the Bergen Festival, and the Festival Exhibition ranks among the highest awards in Norway (past exhibitors include Bjarne Melgaard, Elmgreen and Dragset, and Torbjørn Rødland).

The 1965-born Berg has directed four feature films and numerous short films. Two of her movies deal with the CIA’s cultural engagement during the Cold War, another with Picasso’s portrait of Stalin. Other subjects include sex workers and the surveillance of political dissidents in Norway. With False Belief (2019), she mined her personal history for the first time. In it, she tells the story of her journey through the US legal system after her partner is arrested and imprisoned for racially motivated reasons.

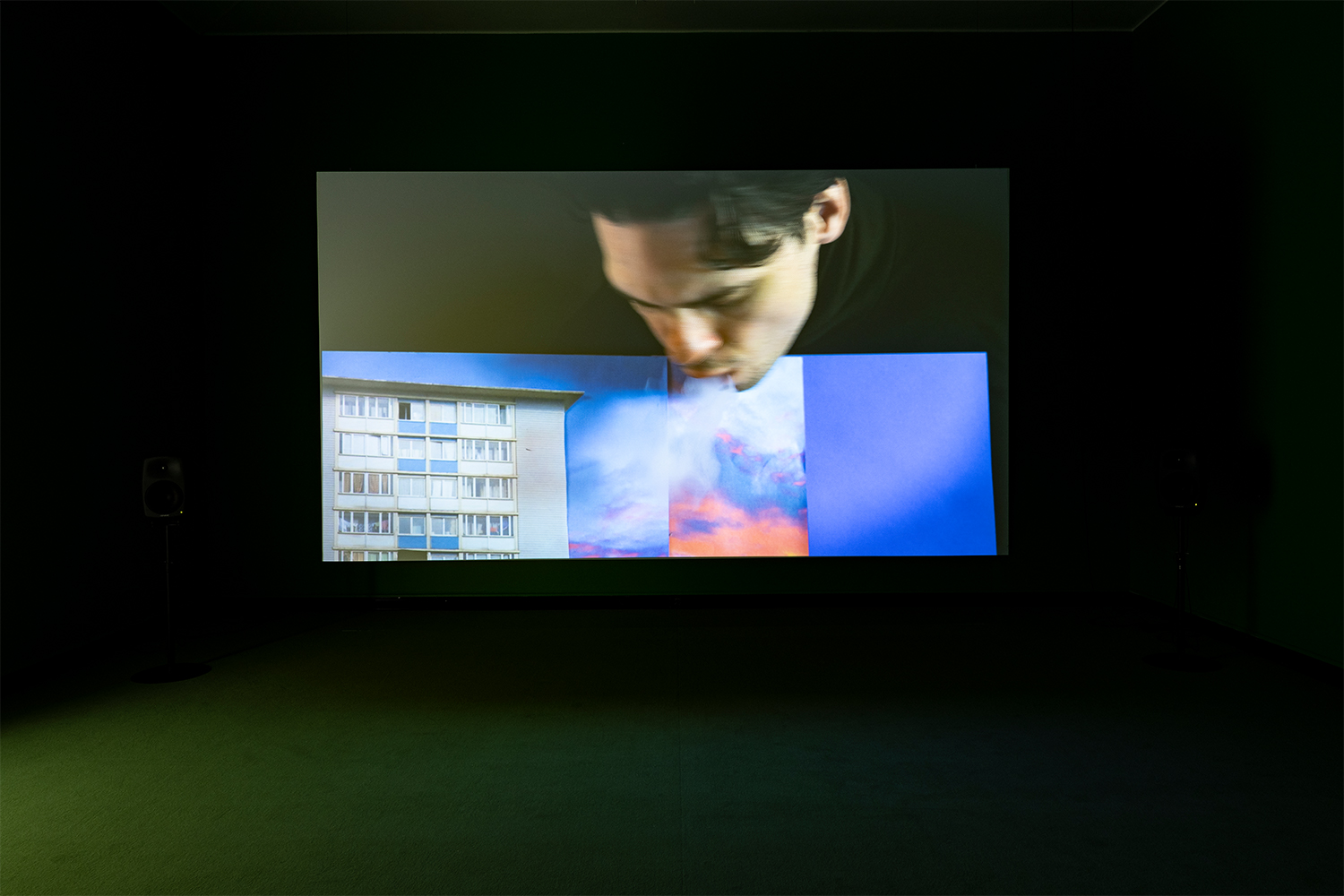

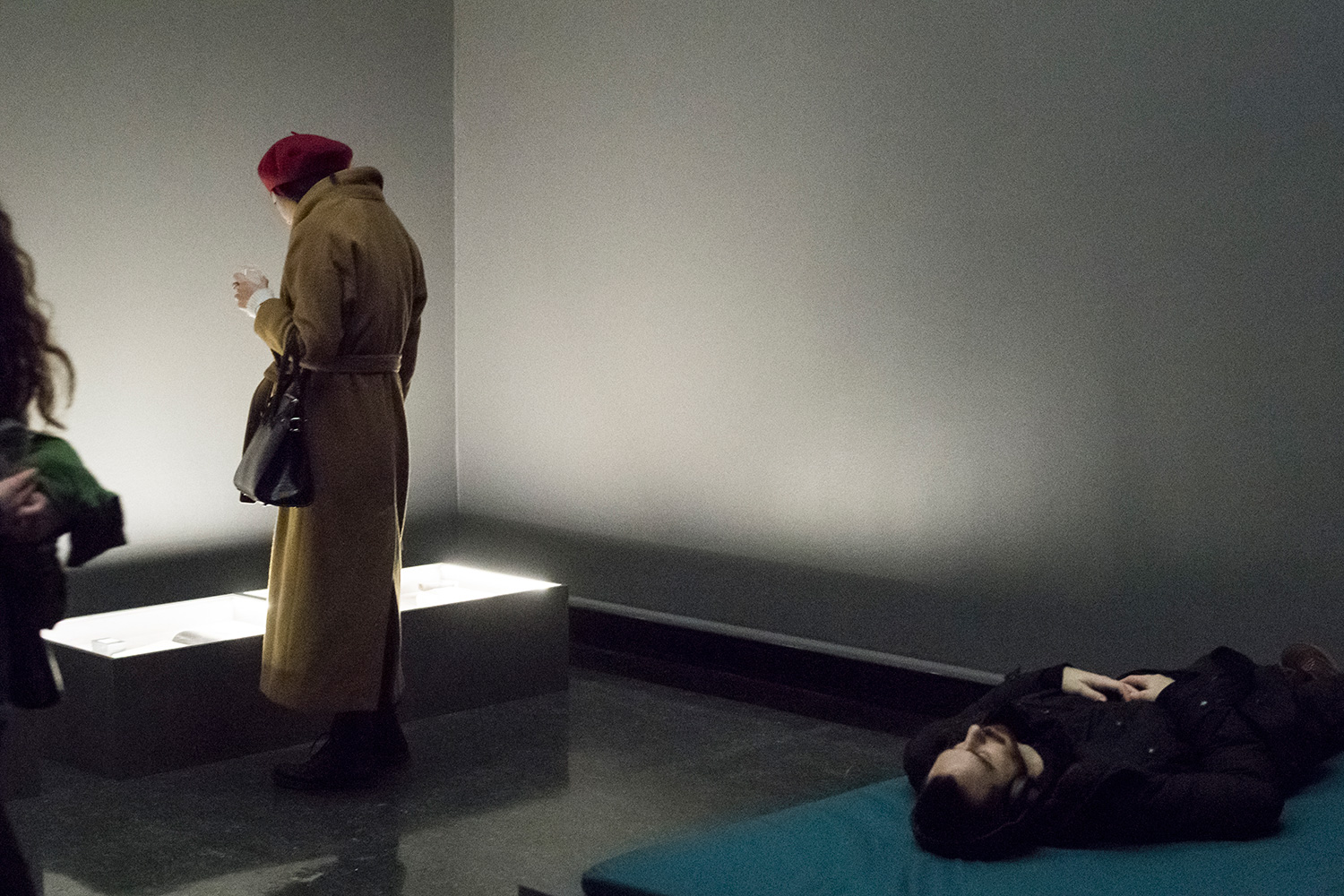

Berg is no stranger to true crime stories, but in the galleries of the Kunsthall, which she had carpeted and blocked from natural light, she unfolds her personal recollections. However, neither the retelling of a crime nor its solution is the point. Walking through the five rooms means following a train of thought. It resembles unpacking a box of old postcards and letters and, at times, sifting through someone else’s memories.

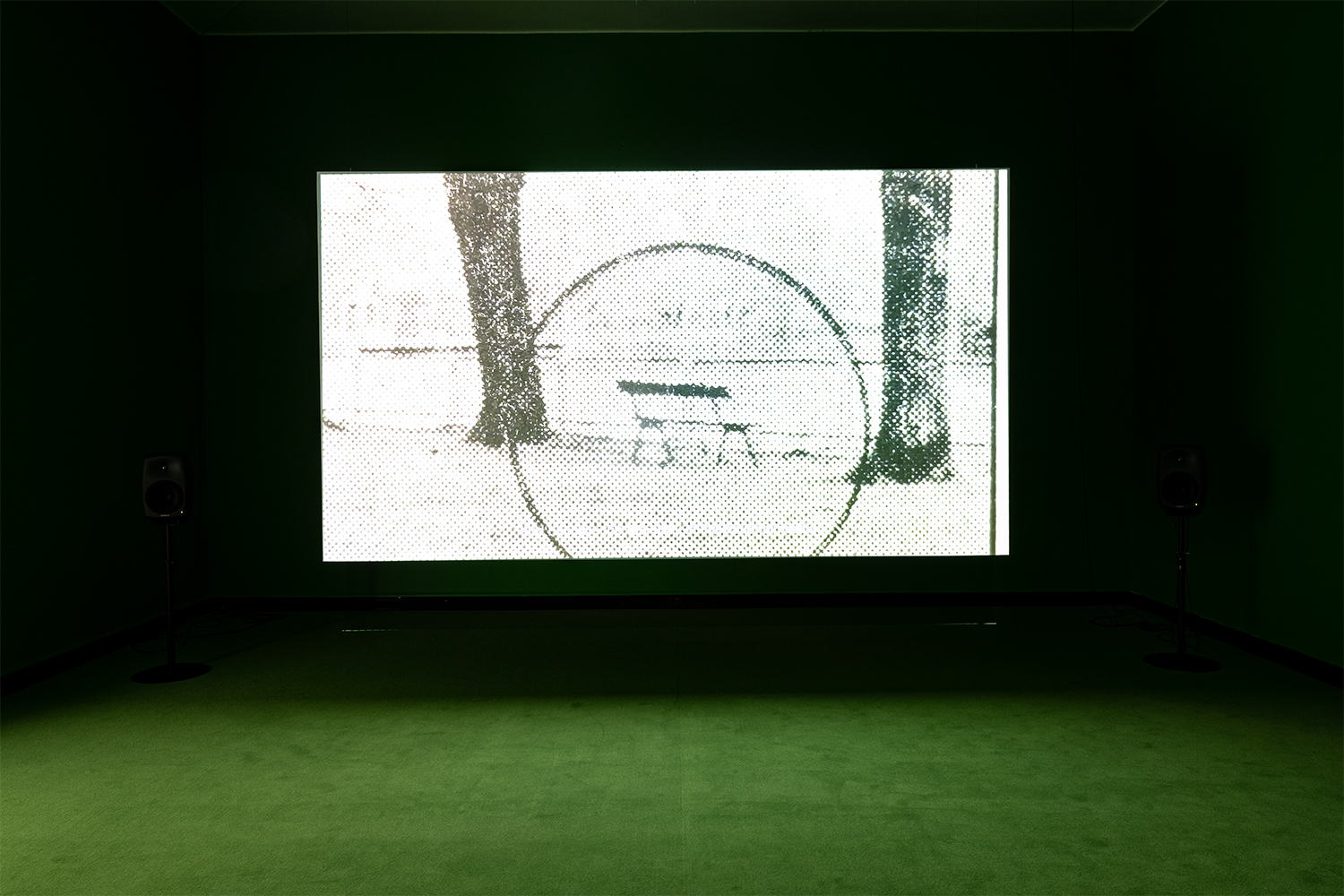

As an entry point to the show, Berg reconstructed the parking lot of an apartment building near the Bois de Vincennes. The diorama she filmed could also be the opening of a feature film. In the lone car on the asphalt, Arnljot Berg is asleep in the driver’s seat, and hunched over his lap is a woman. She is dead, possibly strangled. Berg added a voice-over, full of uncertainty. “Was it in 1974 or 1975?” she asks. This is not a forensic reconstruction, but rather a construction of memory. The dead woman is the actress Evelyne Zammit, age twenty-seven, Arnljot’s second wife. He lived with her in Paris. French tabloids latched onto the story, the father went to prison, and, after returning to Norway, he committed suicide several years later. Despite the danger of falling for sensationalism, Berg tells the story slowly, unraveling and weaving it across the show.

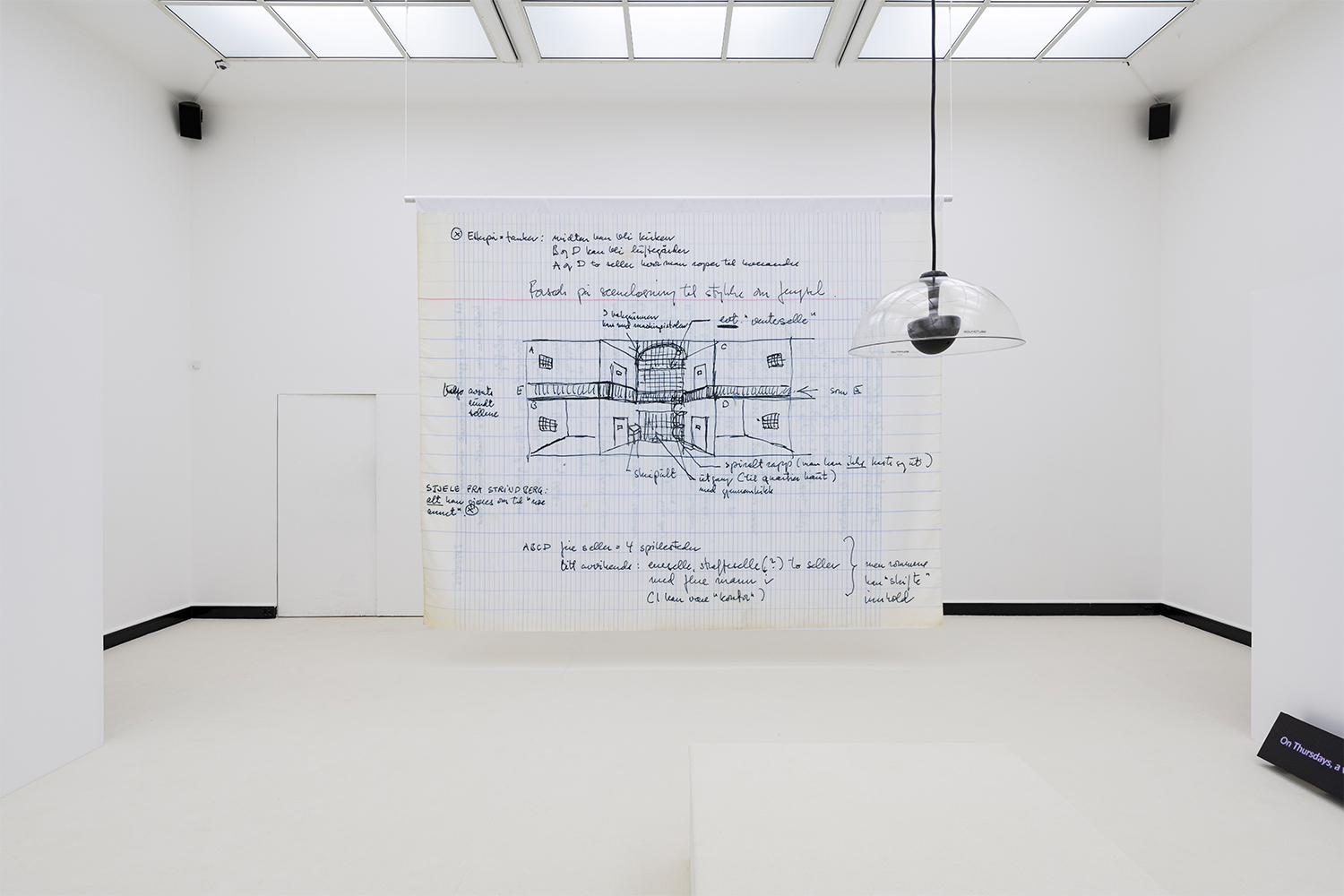

In the mid-1970s, Norway was on the brink of prosperity, fueled by oil extraction in the North Sea. The book and record covers that are reproduced in the show belong to the inventory of a new creative class of educated, probably left-leaning people in the decade after 1968. Arnljot read Godard’s Histoire(s) du cinéma in French, listened to Sergio Reggiani, smoked copious amounts of filterless Gauloises. He was an autodidact from a modest background, who couldn’t afford to go to university yet became one of the country’s leading cultural figures.

Contexts have shifted: the male artist whose mental health issues are a mark of genius has fallen out of fashion, and his crime would now be called femicide. As Berg tries out different media and genres, repeats and reenacts, she avoids a facile use of trauma as a device to add depth. Instead, she dissects her personal archive and allows the story to fray at the edges.

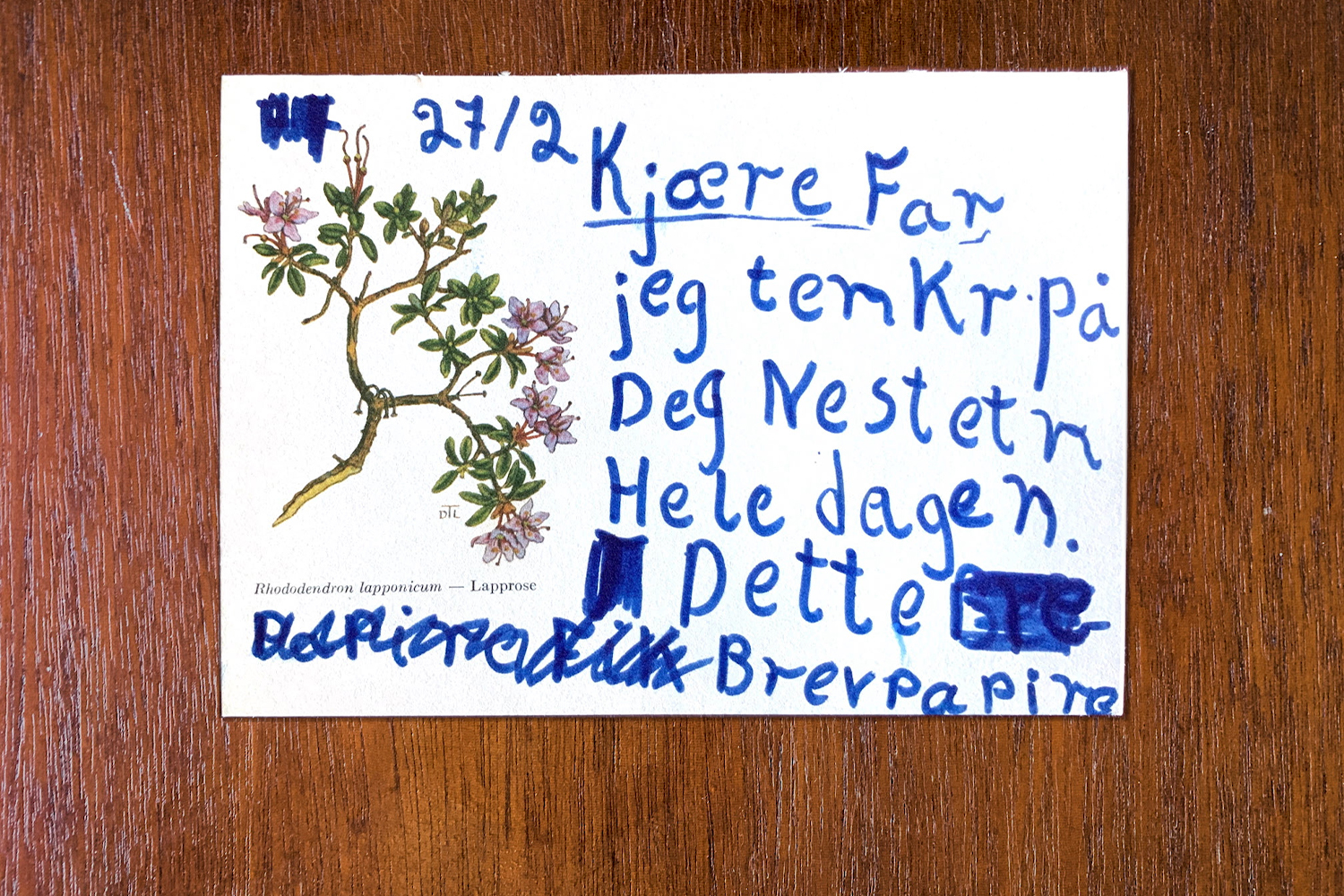

The father’s image as a charismatic, troubled man arises from the show, but his actual picture is absent. The portrait remains splintered and oblique. At least his handwriting is present in the whimsically funny letters he wrote to his young children from prison. Their touching replies are included, and some of them are blown up to curtain-size screen prints that sway gently when visitors walk past.

The concept of exhibiting becomes unstable here. All pieces serve the plot, each one a part of the narrative. None of them can be isolated in a “white cube” way. “Is dad evil, I asked again and again in different ways,” relates Berg, who is turning into the unreliable narrator of her nine-year-old self. Maybe the greatest trick of the show is to make the larger-than-life father disappear behind his belongings and the stories about him.

One of the more inconspicuous elements in the show is an old rotary phone, a prop that runs the risk of tacky nostalgia. But when you listen to the piece played through the Bakelite receiver, you hear Lene Berg telling stories of how her father would vanish for days, just to be found without money, possibly drunk, on the outskirts of some town. No explanation given. At the end of the piece, the daughter says: “Often, I don’t think about you at all.”