In the world there is a single yawn that continues by contagion to spread in search of another yawn to fall in love with.¹

A dilated time, totally arbitrary. The breaking of all routines: daily, sentimental, every kind. A bit like what happens during a hotel stay — estrangement, melancholy, excitement, abandonment… “A Goodbye Letter, A Love Call, A Wake-Up Song” sounds like the title of a three-act score, more like an anti-narrative, confusing at first glance but cynically timely. Tremendously alienating but so real that it sucks you into a loop of images and pseudo-narratives that try to restore the complexity and psychosis of these last years lived as if in a bubble.

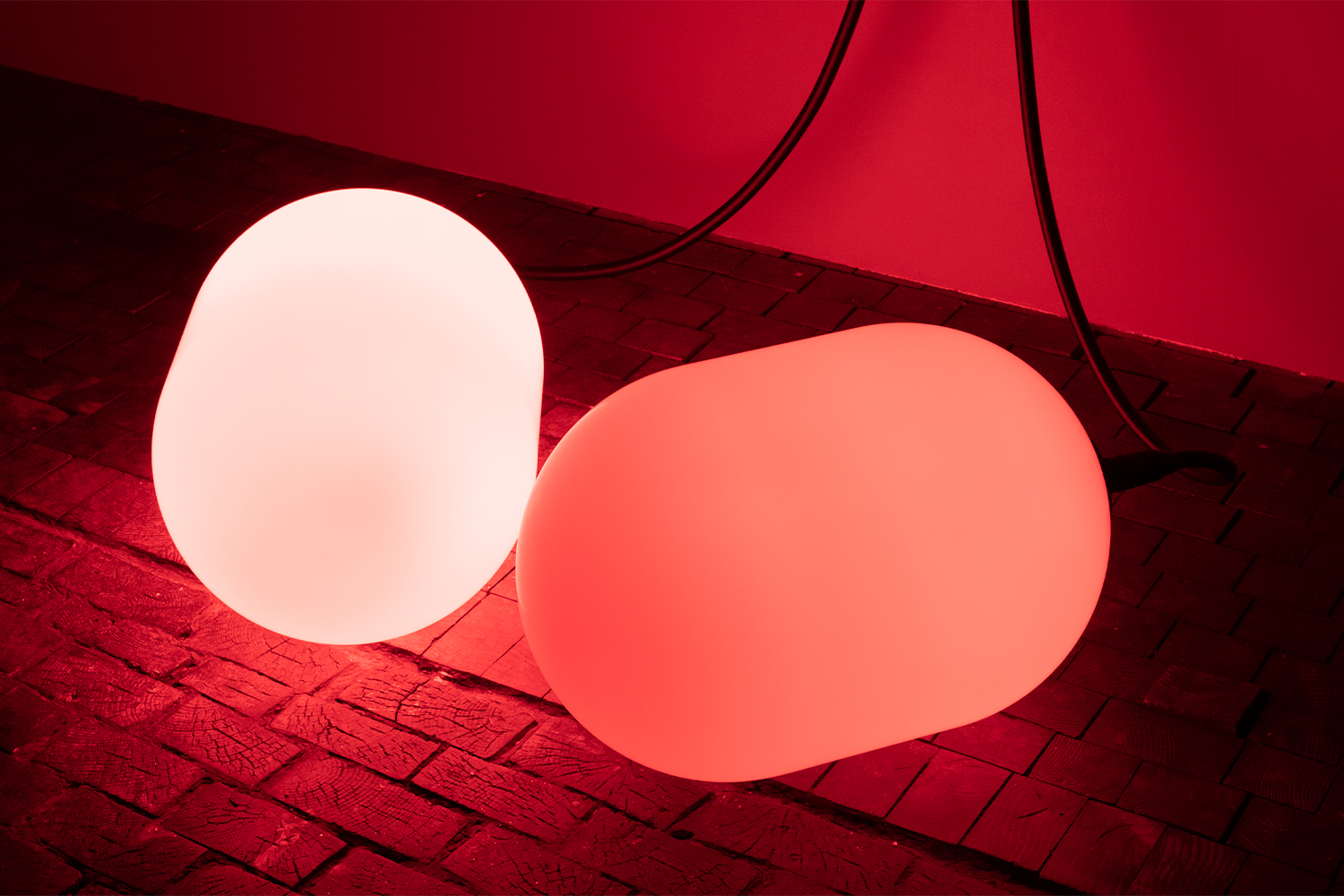

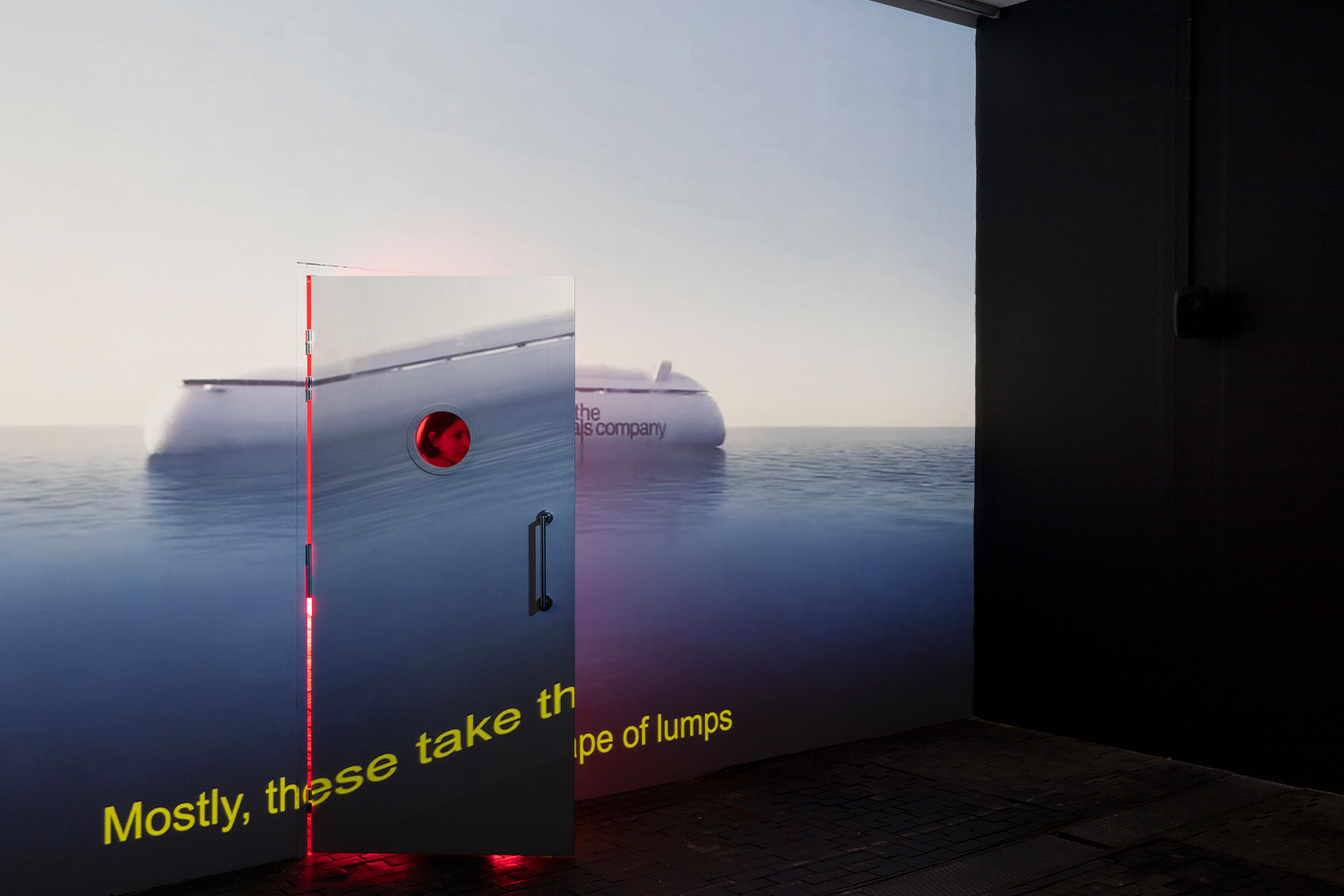

A simulated hotel spreads out over the three floors of the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève. The darkness is illuminated by irregular transmissions of red and blue light via pill-shaped sculptures — Fire (2021) by the designer duo GRAU. These bursts of light expand in a diffuse crescendo throughout the carpeted corridors, altering the viewer’s visual relationship with the space as well as the perceived interval of time spent upon this sometimes-claustrophobic path. Dilation of time is imprinted in this curatorial project, which for this edition springs from two visions, that of Andrea Bellini and the New York–based collective DIS. Here they attempt to sift the rubble, to read the interstitial spaces of our psychological and social environmental. Unlike the previous biennial, generated from another world in which the sounds of screens imploded in images that expanded outward, this time we move almost in the dark amid fourteen suites that host representations of a present-past and a present-future, a realm that speaks about us, that functions as a mirror of a toxic world, hysterical yet somehow still standing.

For me, the experience was like learning to look through images all over again. A sense of alienation is transferred by the exhibition container as a whole, which is closed in on upon itself. Independent rooms, each hosting a different production, are accessible through a labyrinth of entrances that almost disappear in the darkness — an invitation, perhaps, to abandon the sort of claustrophobia that we have been carrying around for a while, but also an attempt to rethink the moving-image exhibition format with one that emphasizes interactions in a physical environment.

The dyscrasia of the room that houses DIS’s latest production, Everything but the World (2021), touches on the absurd. A fluffy white carpet invites us to watch a film, narrated by Leilah Weinraub, in a maximally cozy condition. The room’s set design is seemingly playful, yet viewers are inevitably made uncomfortable by cold air blown from ceiling fans. And while it’s true that one can choose to warm up with one of the electric blankets provided, the film’s dysfunctional narrative — which begins with a depiction of a “typical” man trying to reinhabit a postapocalyptic setting he essentially no longer recognizes — keeps you in a perpetually disturbed in-between state, epically flavored by the manic sketches of Lizzie Fitch and Ryan Trecartin, who try to question linguistic hierarchies now in need of rethinking. Everything but the World could easily be the subtitle of this biennial, which does not lack for ways of communicating the contemporary discomforts and failures of language, politics, and identity.

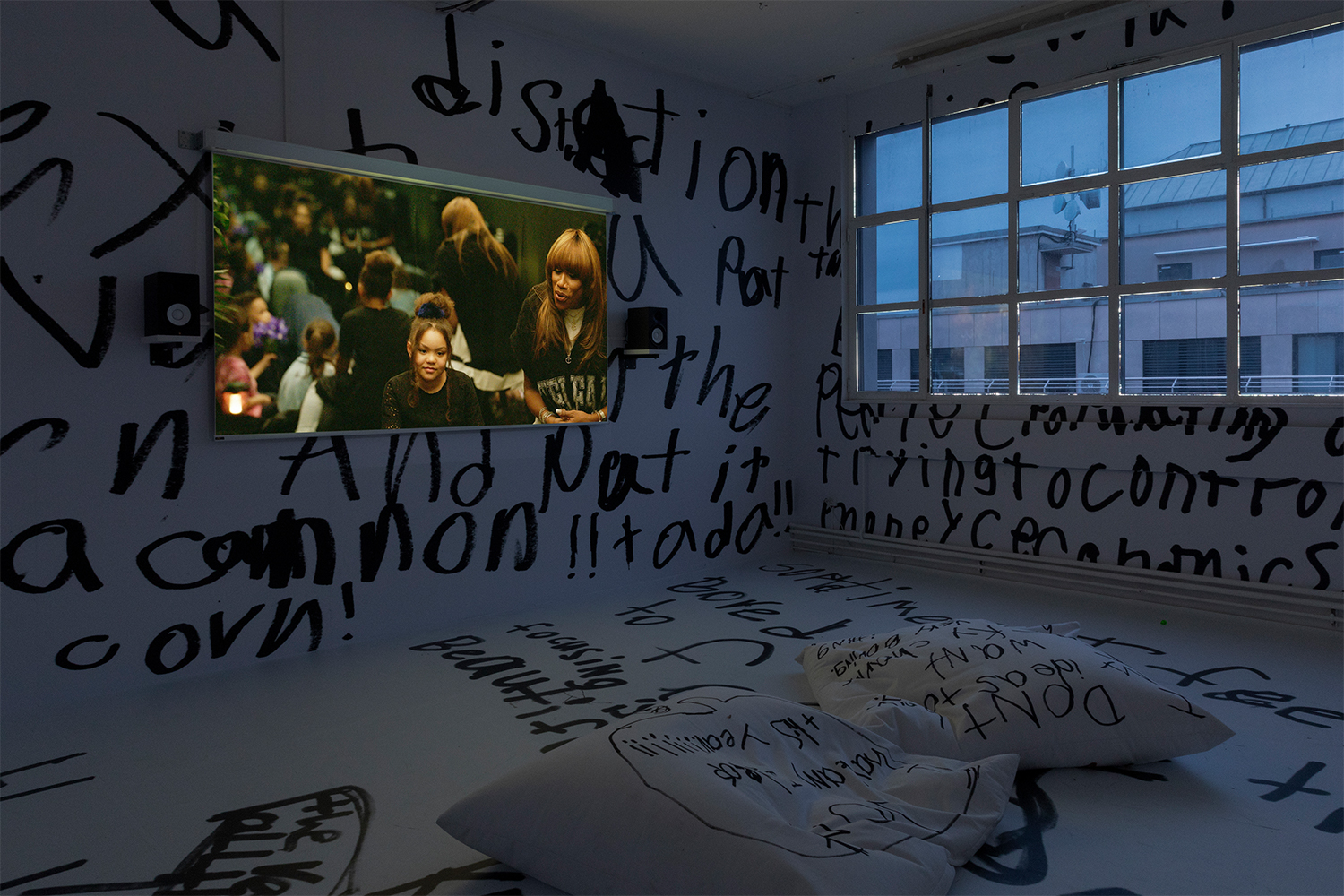

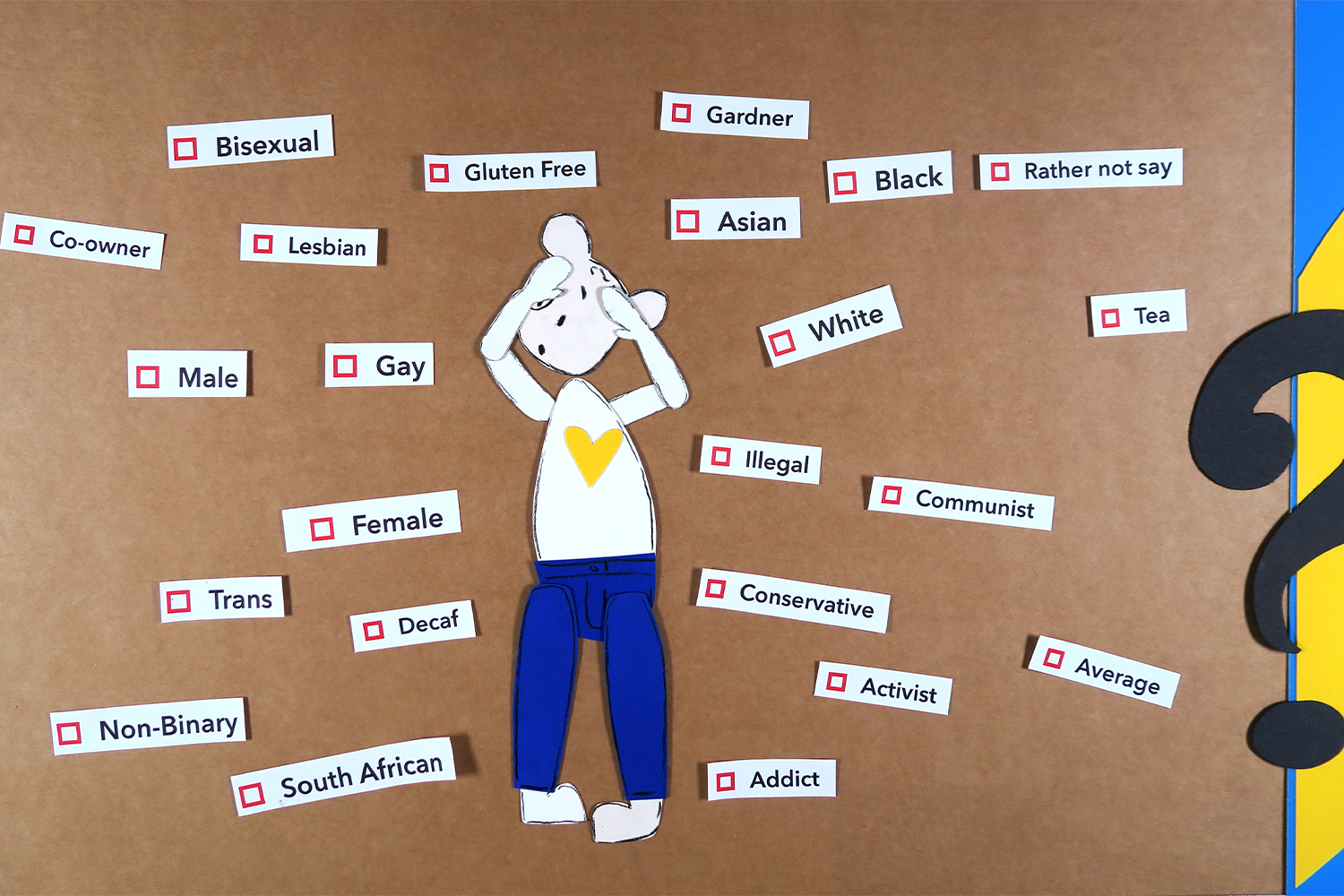

A rush to reeducate, shamelessly suggested by the exaggerated aesthetics of the show can be seen in Couture Critiques (2021) by Mandy Harris Williams. Using the visual and editing framework of “House of Style” — an MTV program (1989–2000) about the lives of supermodels — Williams tests the aesthetics of information by repurposing Edward Said’s legacy of “speaking truth to power” and his Representations of the Intellectual (1996). Or in DIS’s Circle Time (2021), an educational program made in collaboration with TELFAR, edited by Trecartin, that was developed with NYC children’s communities during the closing of public schools in New York City in 2020: “How can you be strong?” is one of the questions that invites young children to think about the importance of building the self. A self that in the stop-motion, digitally animated film Once Upon a Who? (2021) by Simon Fujiwara remains poised between the inability to self-define and annihilation. Meanwhile, in Sabrina Röthlisberger Belkacem’s Santa Sangre (2021), the self is a portrait of a woman lost in a landscape of ruins, engaged in a hard process of acceptance somewhere between decadence and reconstruction.

Is it superb or far-fetched to claim that a biennial, with fifteen time-based productions, manages to mark the present so aptly? Perhaps we just have to accept that an exhibition project without conceptually well-defined thematic pretensions can still manage to say something, leaving the field “open.”

There’s also plenty of fiction evident in the creation of parallel scenarios, such as the rainforest with a huge skyscraper filled with restaurants in Will Benedict and Steffen Jørgensen’s The Restaurant, Season 2 (2021), in which multispecies chefs experiment with new cooking show formats. Fans of film noir will take note of Emily Allan and Leah Hennessey’s Illuminati Detectives (2021), based on a screenplay they wrote during a residency at CERN, which reimagines poets Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley as X-Files-style agents.

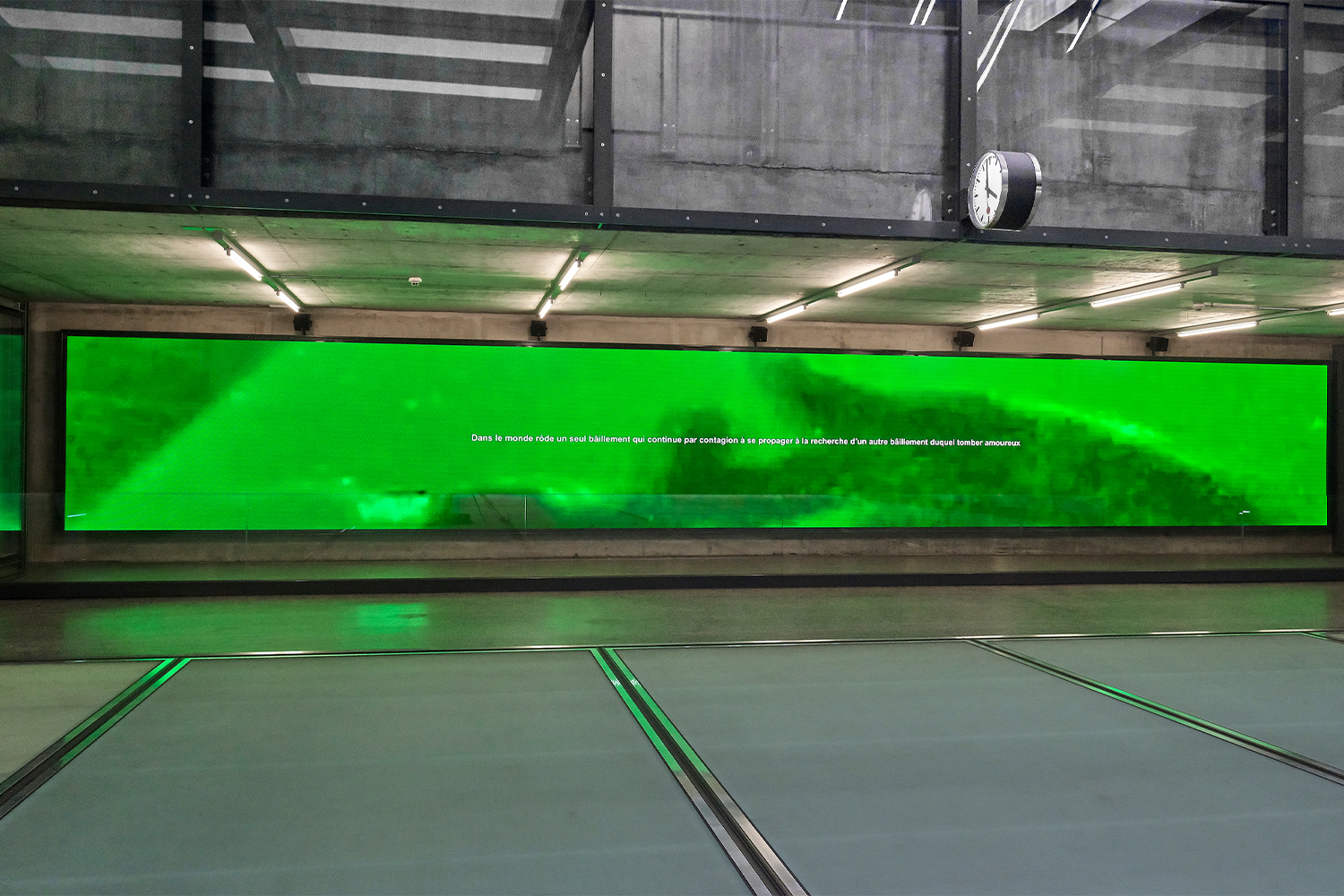

And then there are other phases of “awakening,” as in Giulia Essyad’s BLUEBOT: Awakening (2021) — shown in both the dystopian hotel and the Chêne-Bourg station — in which blue mini-dolls (a nod to colonial alien fiction) awaken from a long “hibernation” in a posthuman reality and must reckon with the possibility of rewriting their own story. Or the timid awakening implied by the reimagined dance floor of Riccardo Benassi’s site-defining work Daily Dense Dance Desire (DDD) (2021), a three-minute loop spread over the seventeen meters of the Champel Léman station corridor where sounds and green lights softly reverberate, the grain of the image made visible and dirty due to human footprints, dust, and other effluvia. The “real” manipulation of the opaque images we are able to grasp derives from the error and failure of technology, in this case the result of using GPT-3, the most advanced predictive language AI software. Benassi’s attempt to simulate himself in the machine retains an existential dimension, suggesting a desire for self-preservation of the ego or a desperate last act, like writing a lipstick dedication on a bathroom mirror. (Anyone entering the bathroom of the CAC will find this bittersweet message: In the evening I tried different smiles for you and repeated each smile several times over, but then threw them away as soon as they withered.)

A cynical solipsism reverberates in Penumbra (2021), a CGI rendering, developed by studio And or Forever, of the performance of the same name conceived by Hannah Black and Juliana Huxtable for PERFORMA (2019). It is a staging of a mock trial of animals for alleged crimes against humankind, attended by nonhuman witnesses, in which Hannah Black’s avatar prosecutor debates Juliana Huxtable’s pangolin defense attorney. The solemnity with which they both approach the trial ridicules the debate over anthropocentrism and stages a subtle but obvious critique of the impossibility of truly considering ourselves as “ecological beings” — to echo Morton, whose phrase “genders are shelled animals”² ironically comes to mind.

We will be forced, always and in any case, to face the world through the lens and body of a human species inevitably marked by the many superstructures that have legitimized our image of the world. Everything but perfection, I would say.

Will it be our fictional beings or a new empathy that will completely reset us? For now the hotel has closed to the public — until the next time.