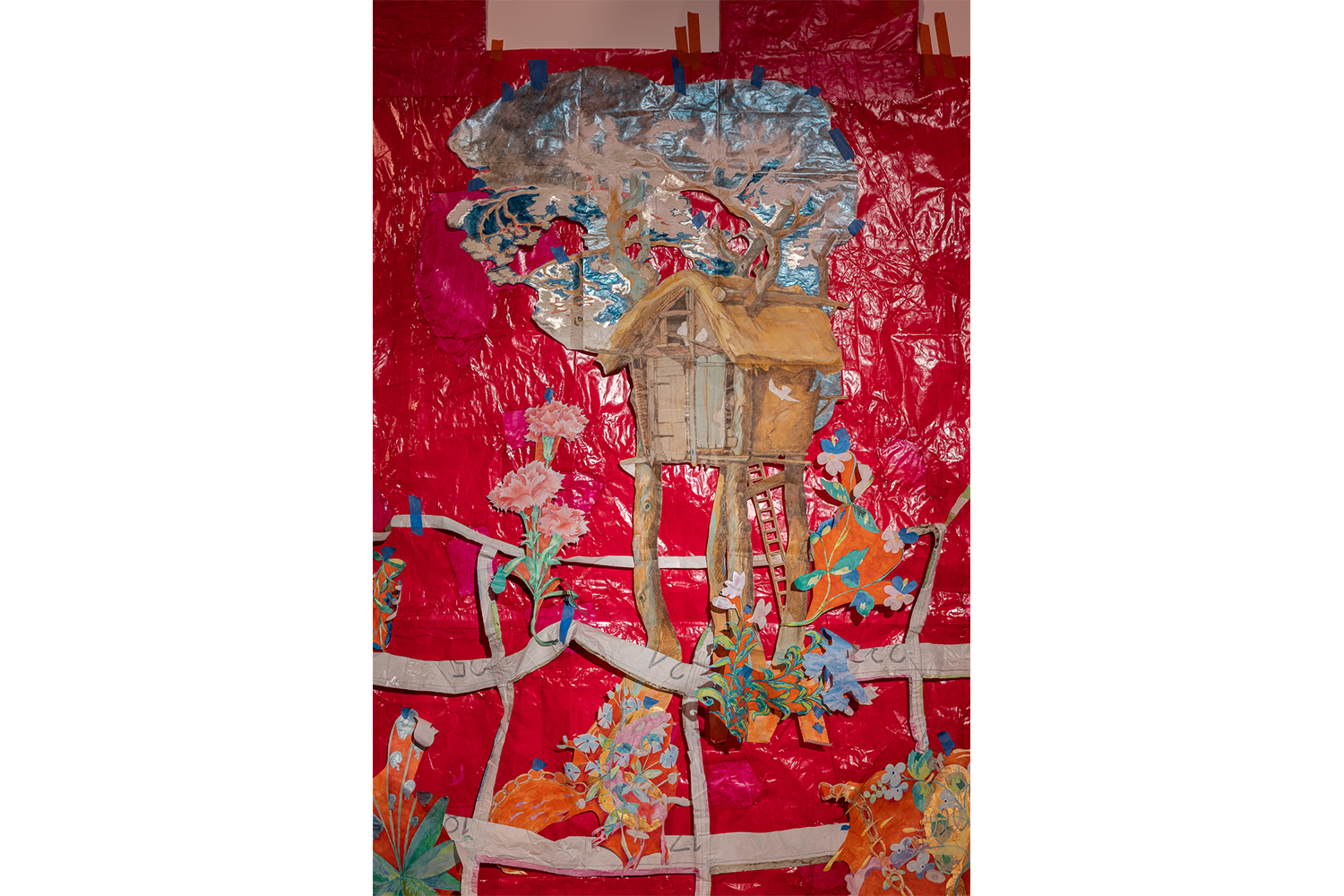

Creased, flattened-out drawings, loose cuttings, intricately labored paintings, slimy melted plastic, industrial-size tunneling machines, the flaccid limbs of figurative characters, scribbled text, seductive surfaces of marbled Jesmonite, a ceramic figure disembodied, detailed renderings of Fortnite characters, a story of a man who attempts to eradicate time, rubbish, a multitude of performed accents and voices, notes on the backs of painted sheets, other things and non-things: Sam Keogh confronts the viewer with an entanglement of materials, semantics, and conflated narratives. The Irish artist utilizes a wide array of mediums and methodologies to realize his exhibitions and interdependent performances. Keogh often acts as a mediator or gatekeeper to the surreal and hyper-saturated worlds that he constructs.

Keogh is currently based in London, where he has just opened a new exhibition at Goldsmiths CCA, London, titled “Sated Soldier, Sated Peasant, Sated Scribe.” I followed the artist through the basements of Goldsmiths CCA as he gathered and salvaged his static, albeit precariously installed (paintings taped to the wall), artworks from the exhibition for his performance at the front entrance of the gallery. The walls bulge with dimly lit drawings and paintings that seem as if they could fall down at any moment. Keogh snatches a fabricated alicorn (unicorn horn) from the gaze of a mesmerized viewer; it will now be used as a prop in his performance. The viewer follows. Outside, a crowd gathers and Keogh lures his audience in by silently constructing an image, a world, a story before their eyes. The exhibitions Keogh amalgamates become platforms for a host of characters and associations.

Frank Wesser: Sam, your work is often populated with characters, for example Oscar the Grouch, a depressed space traveler, an animated worried clock, a pig who is a pig, that is to say, a border control cop. These characters regularly transcend from flatness, or images, into performed gestures where you animate your own body and voice. How does this happen?

Sam Keogh: The first performance in this vein was Taken Out of/Put into Oscar’s Bin (2013), a kind of partially memorized text which attempts to describe Oscar the Grouch through a constellation of fragments, or a chorus of countercultural histories and materials. I thought of it as a way to take Oscar out of his trash can, where he was quarantined in the universe of Sesame Street, and make him more than his function (if his function is to teach kids about liberal notions of tolerance of non-normative behaviors). In that sense, I was treating him as a manqué, or as a figure who failed to live up to his own promises, and to kind of reanimate him and give him what he originally promised his audience. So he’s the first time I tried this thing of pulling a recognizable character out of the flatness of their recognizability, maybe. A similar operation happens with some of the other characters you mention, where they are plucked from a fictional or folkloric universe and manipulated into life through performance.

FW: Flatness persists throughout your work and to a large extent in this exhibition. But it’s a flatness unfurling: we can often see behind or even through a drawing, or a tease of something beneath an object, and this reinforces the impossibility of seeing the whole thing. Can you speak a bit about this aspect of your work?

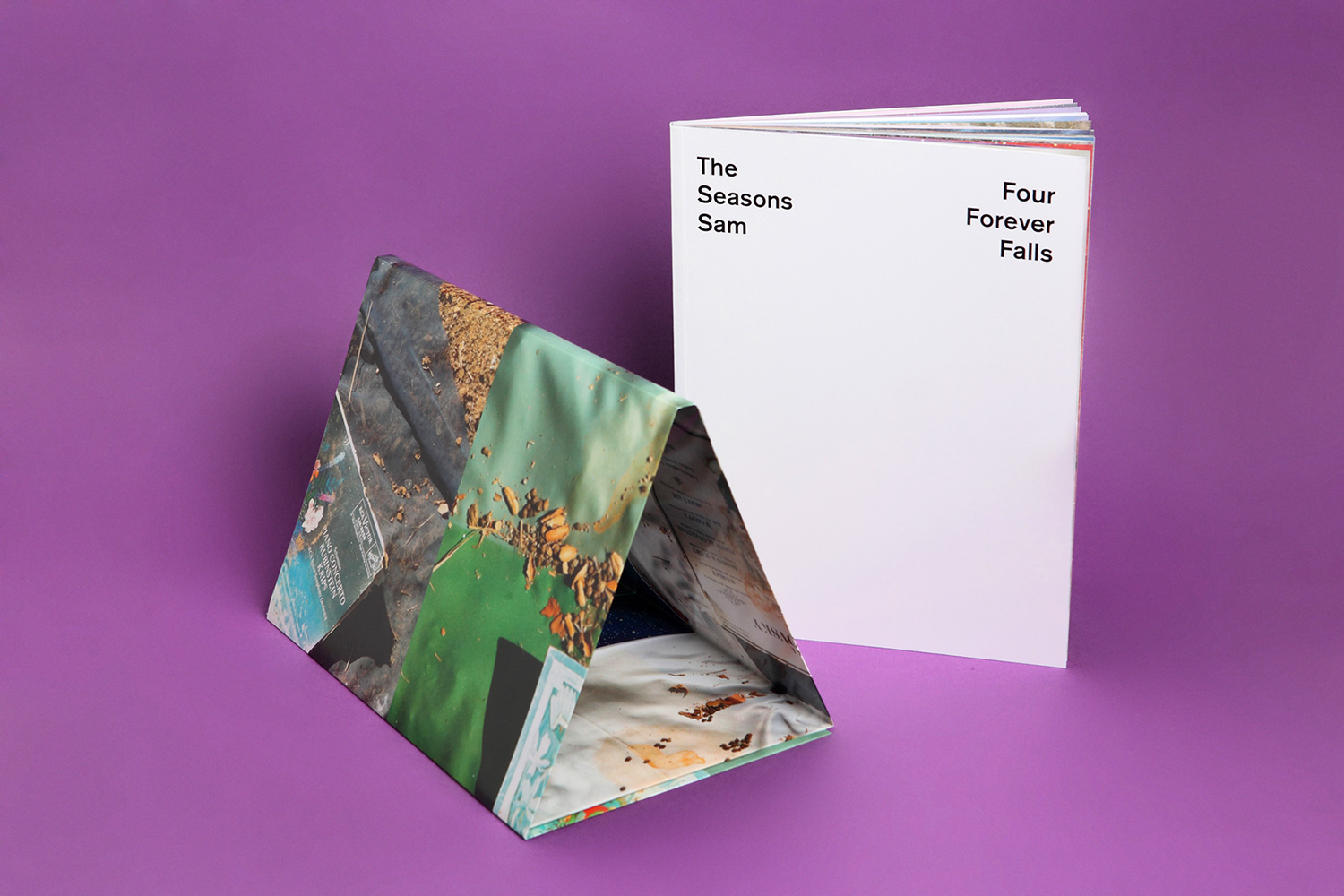

SK: With this current show in CCA Goldsmiths, this flatness is quite literal. Everything is made on layout paper, a kind of paper used by designers or illustrators. I like how the thinness of this paper holds the labor of drawing. It can support a lot of detail, but crumples with moisture and bears the marks of pencils in a particular way. The drawings that make up the colleges are also folded. Everything is folded actually, including the very large sections. This was in part a reaction to the pandemic and Brexit, which made shipping big cumbersome art objects tricky and also fucked up the post at the start of 2020. So I decided to make these things portable. Most of the paper elements were folded up and pressed into a suitcase which I flew back to London with. The border guards in Stansted Airport saw the cheap new suitcase and thought I might be smuggling tobacco, so they searched it. They were confused to find all these drawings of flowers and unicorns, but as the work’s first audience I folded them into the story I tell in the performance.

FW: Where do these images come from?

SK: To briefly describe where these images are drawn from, they’re from a combination of paintings and tapestries which have some relationship to pre-modern myths of abundance, laziness, or anti-work. In particular, The Land of Cockaigne (1567) by Bruegel and The Lady and the Unicorn “millefleur” tapestries made around 1500 in Flanders. Flowers, food, sleeping figures, and mythical beasts from these works are collaged together with a Microsoft Teams calendar, Fortnite avatars, inhalers, and other icons and ephemera from contemporary life to form anachronistic combinations of variously rendered signs and symbols.

And yes, a lot of these works are worked on both sides. I like how it frustrates a quick frontal reading. It’s also an easy way to make an image into an object, and to make people have to move around it, find a spatial rather than just scopic position in relation to it, and to hold people’s attention for a bit longer. It also makes you as the viewer do some of this unfolding, I suppose.

FW: Can you tell me a little bit about the script or story that seems to bind together each of the separate elements in this latest work at Goldsmiths CCA?

SK: This story is basically the story I mentioned, of my bag being searched in Stansted, but “dressed up” in the contents of the bag. The drawings of flowers, sab cats, Situationist posters, and Fortnite avatars are all either invoked or used to trigger other side stories about sabotage, millefleur, Jean Genet, or the origin story of the red flag of socialism, etc. So, it’s a story about the opening of a bag and the unfolding of its contents, which in turn nests other stories and references.

The border guards are figured as a unicorn, a roasted pig, and a worried cartoon clock (again, drawings which were in the bag and which were made before the script was written). Transforming the border guards into these fantastical entities made them malleable. I could move them around, tear them, or even kill them and eat them (as I do with the pig). They are kind of inflated into life through text and speech, so they can be killed or flattened again, or re-contained as images. It also echoes the rest of the work’s treatment of signifiers of “the political” — they are played with and profaned, used to collage a world where everything is for everyone, where the police can be eaten and where calendars can be repurposed as a rose trellis.

FW: Hold on, it’s interesting to hear you speak about flatness, but there is often a distinct feeling of something being unfurled, and that isn’t to say straightened out.

Your politics seem undeniable in the work, but they might be at risk of contamination by the institutional framework they sit within. How do you position yourself in relation to the inherently contradictory institutions of the art world (universities, museums, galleries, etc.)? Do you think your work is an act of solidarity?

SK: I don’t think I can call my work an act of solidarity, because this word for me describes a process of deindividuation. What I’m doing is pretty authorial in a traditional sense — I do everything and then I show everyone what I’ve done. And I kind of agree with Moten and Harney when they call for the abolition of the category “artist” as a kind of uber-sovereign individual, the one exception to the rule of alienated labor under capitalism who gets to live out the ideal of “free expression.” So, I don’t think I can claim the work is an act of solidarity. It’s just an installation and a performance.

But solidarity might happen if I withdraw my labor or acknowledge a picket line and not cross it, which is likely to happen over the run of the show. Goldsmiths UCU has just voted for strike action to defend fifty-two jobs. The reason these jobs are at risk is now typical across the board in UK higher education — the whole edifice has been hollowed out by years of Tory cuts and privatization, and what’s left is being eaten alive by a chimera of upper management, consultants, and VCs on massive salaries.

FW: Do you work in any of these types of institutions as an educator?

SK: I teach in another less-well-known art school in London, and despite being on a permanent contract, I too was put through a redundancy consultation mid-pandemic. The experience completely changed my attitude towards the institution. I now see it as almost hopelessly venal, and the art school in particular as doomed. For some time, I had fantasies of resigning on principle. But after interrogating myself a bit, I decided that would be an act of totally ineffectual martyrdom. So now I just teach what I want, support my students, go to union meetings and wait for them to try and sack me again, LOL.