Clothing has long been a signifier of sorts. On a global scale, the ecosystem of fast fashion is often conflated with exploitative systems of labor, production, mass consumption, and commodification. Whereas on a quotidian level, clothing signifies identity, class, and niches. For Yin Xiuzhen, a garment is both a perfect signifier for and embodiment of memory; it is an opportunity to tell a story. “Sky Patch” presents an intimately personal story, yet one in which the perspective constantly changes. The volatility and delicacy of storytelling is at once questioned and fulfilled, and failures are acknowledged.

More often than not, when artistic practices touch upon the fashion and textile industry, there is an accompanying critique of the fashion ecosystem in relation to the current extremities of our late-stage capitalist society. The discourse of long-needed “change” or sustainability has lingered far longer than any concrete action that has been taken. In “Sky Patch,” sweeping critiques of the industry’s excesses are set aside for a subtle and personal rumination on China’s rapid industrial and social development over the tumultuous period of the 1960s until the 1990s.

Yin imbues the exhibition with emotion, drawing from her own memories as well as a collective generational history. In My Clothes (1995), a photographic series archiving a project she embarked on titled Dress Box of the same year, Yin collected garments from the previous three decades and folded and sewed them in such a way that they could never be unfolded again. Archiving them in a box, she then poured concrete over them to encapsulate them forever. Such thorough documentation recalls the notion of hoarding, but is here grounded in the artist’s deep psycho-emotional identification with and personification of these objects. They also invoke the simple reality of clothing’s scarcity in China at the time. Hand-me-downs could last from one generation to another, at once fulfilling a utilitarian purpose and providing a conduit for memories.

Factory Floor (2020) replicates Yin’s childhood memory of visiting the factory where her mother worked. Two parallel lines of sewing machines face one another. Clothing heaps, industrial textile supplies, and daily necessities sit in the middle of the room. The scale model suggests a strong sense of communal work — one of the crucial aspects of Chinese society that propelled the country out of collective poverty. The disarray of the piled clothing brings to mind the squalid sweatshop-like conditions that factory workers must endure. Still, such criticisms feel far from the forefront in this work. The mounds of clothes permeate the room with a sense of tenderness and longing: a personification of what these items mean to Yin.

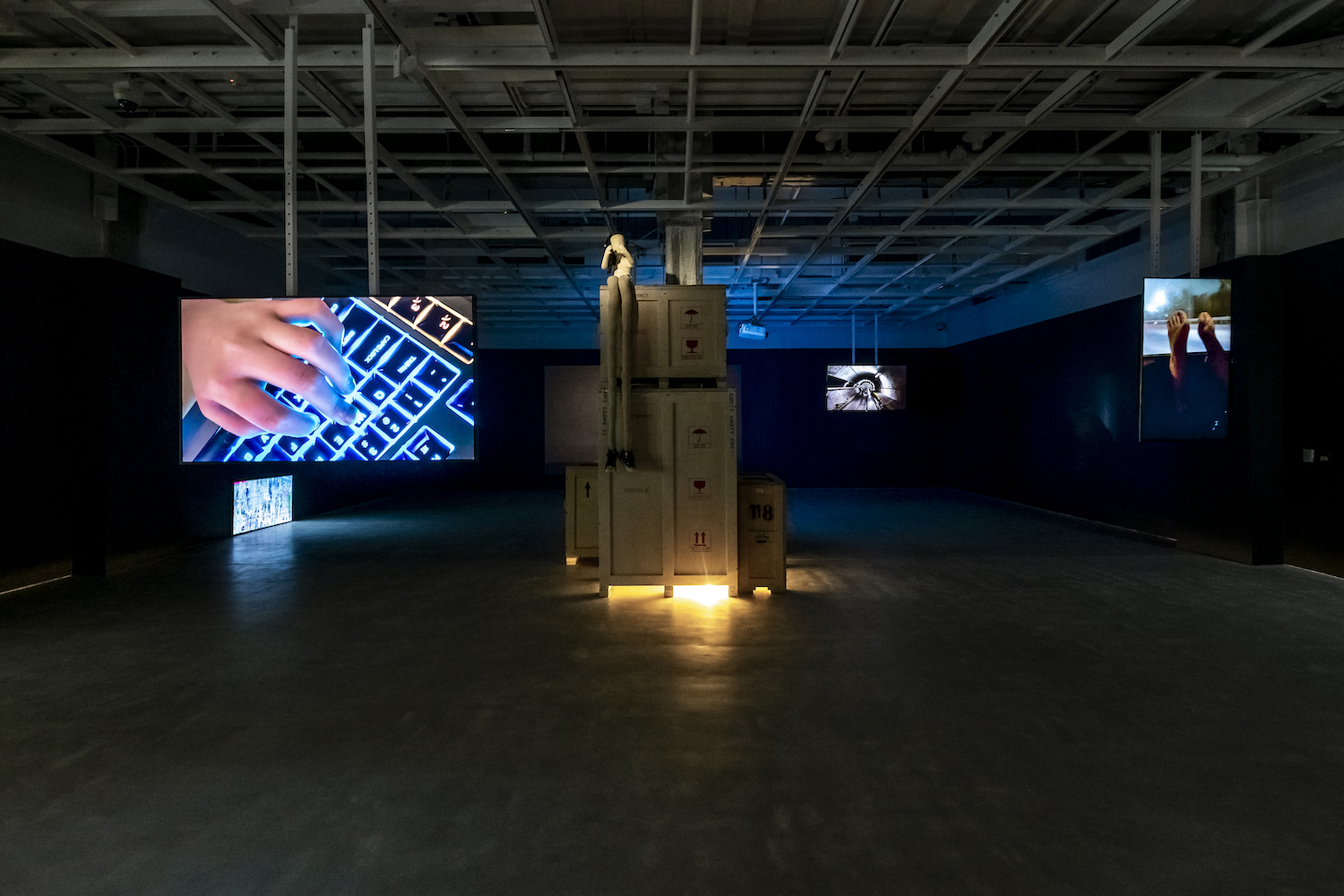

Initially the curation felt choppy and disjointed, jumping back and forth between seemingly disparate subjects — from video works of Yin’s daughters to knitted cotton sculptural pieces. Only upon reflection did I recognize the similarity to how we conceive our own lives via patched together generational memories. Our lives and sense of self are just as fragmented as the world appears — yet within our own worlds and narratives, the common thread holding the “sky” together still is compassion, warmth, and love. Perhaps we’ve just lost sight of this.