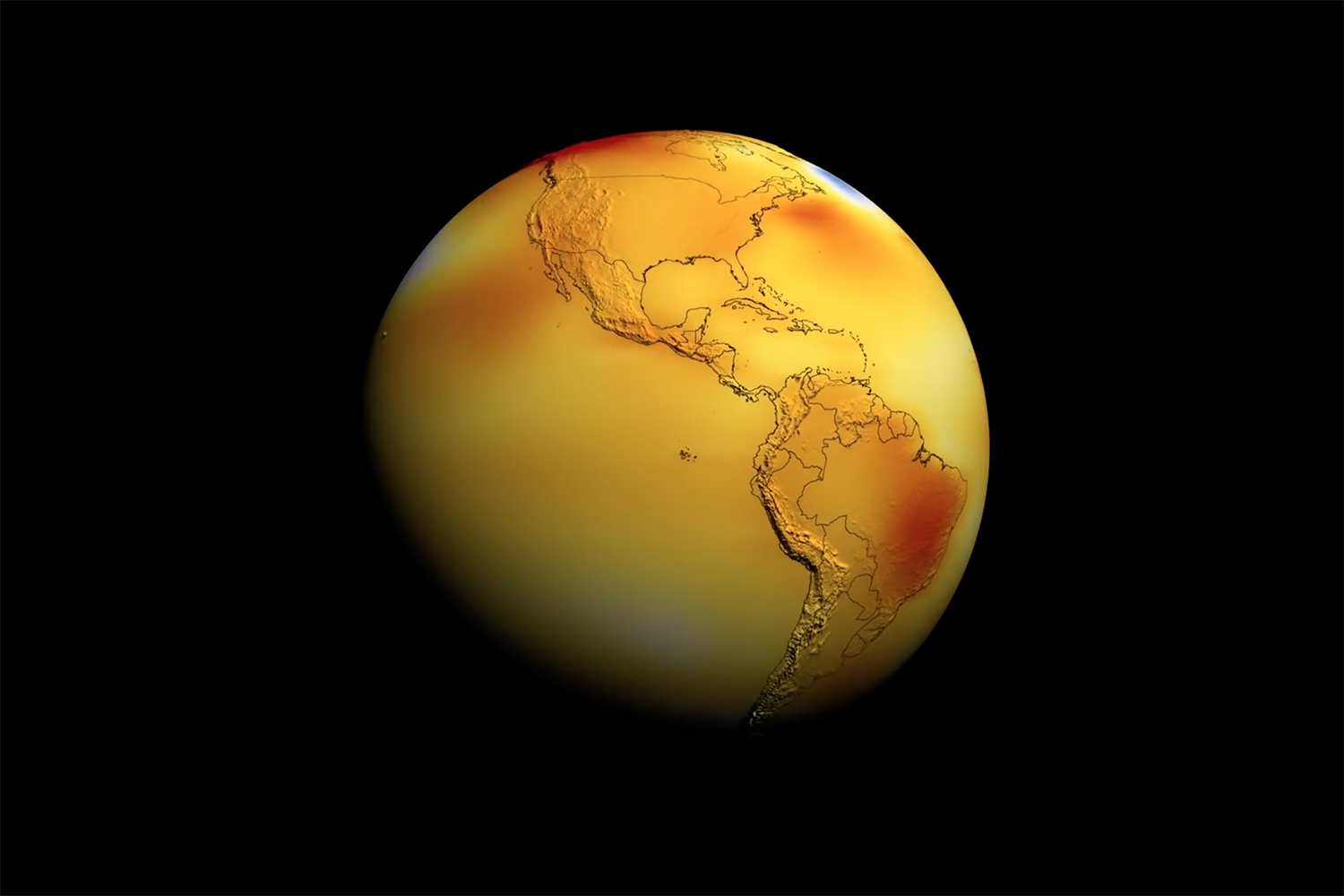

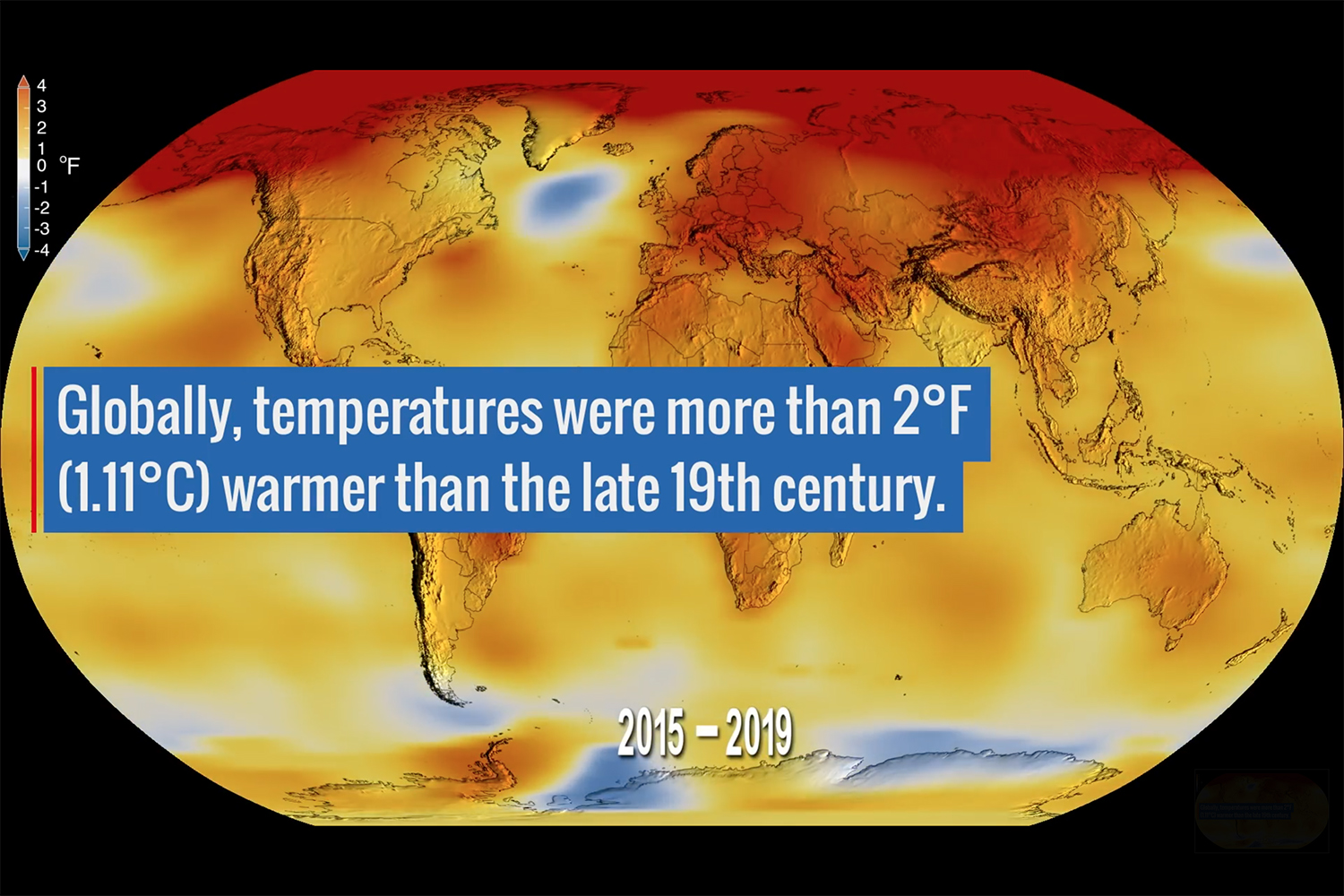

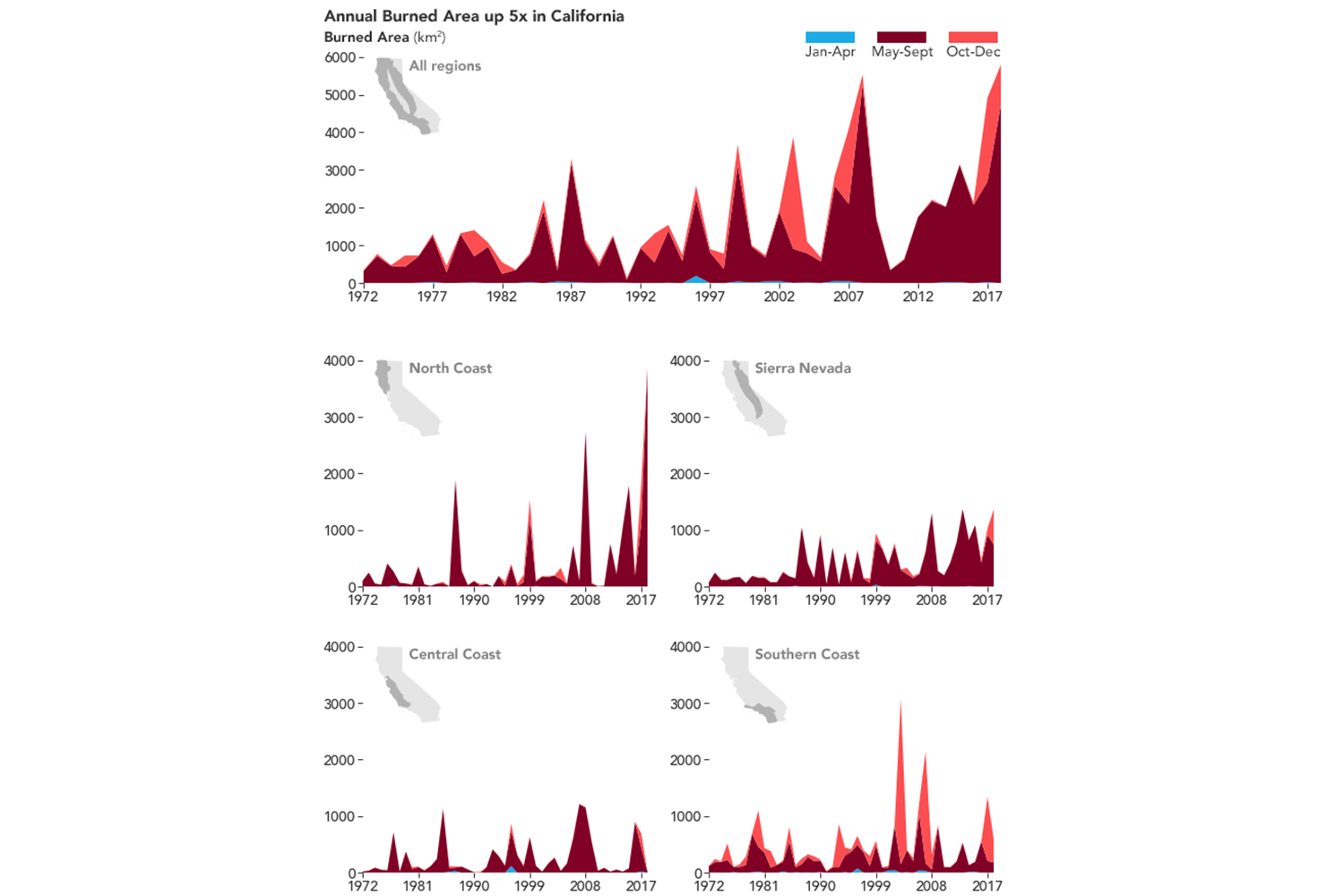

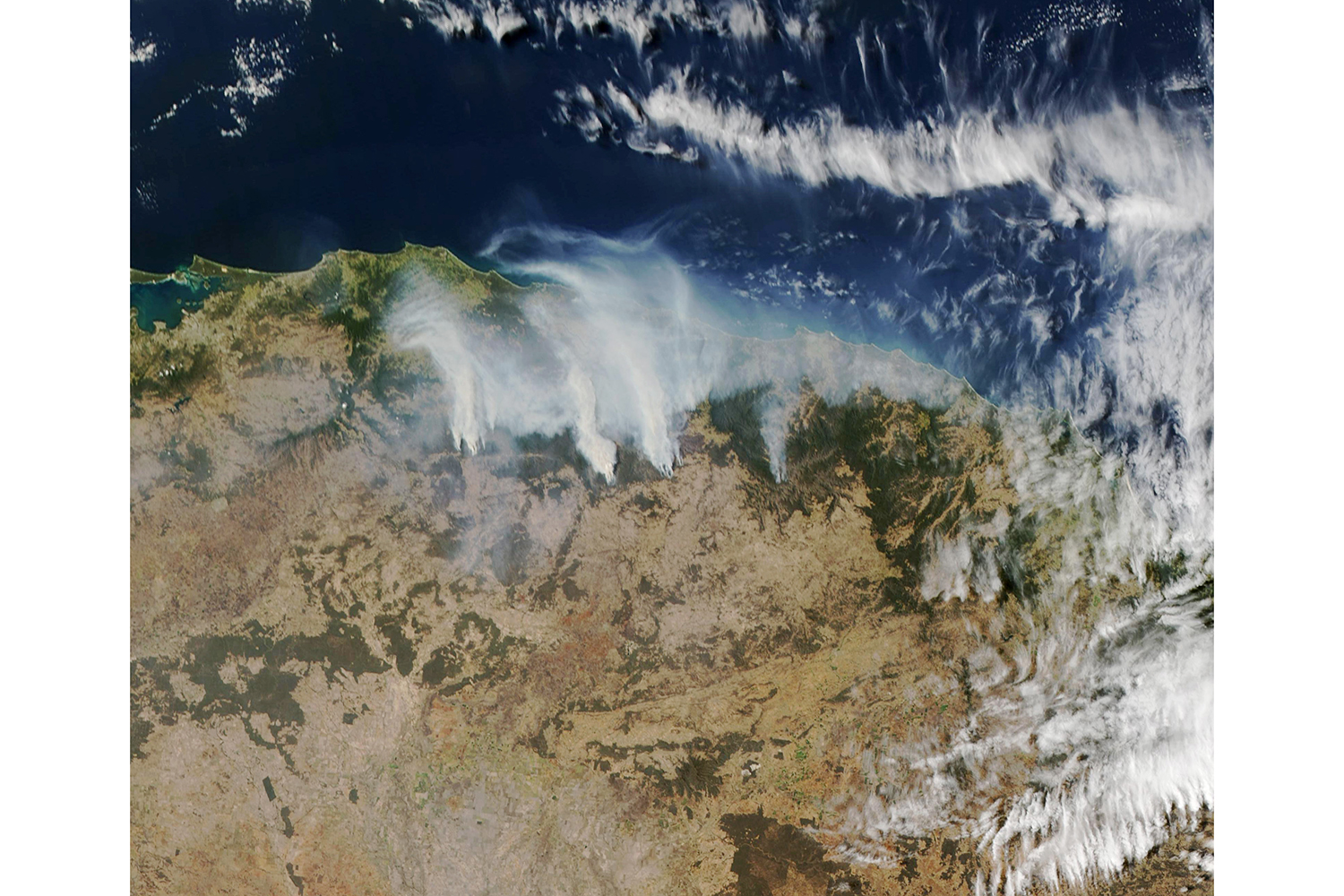

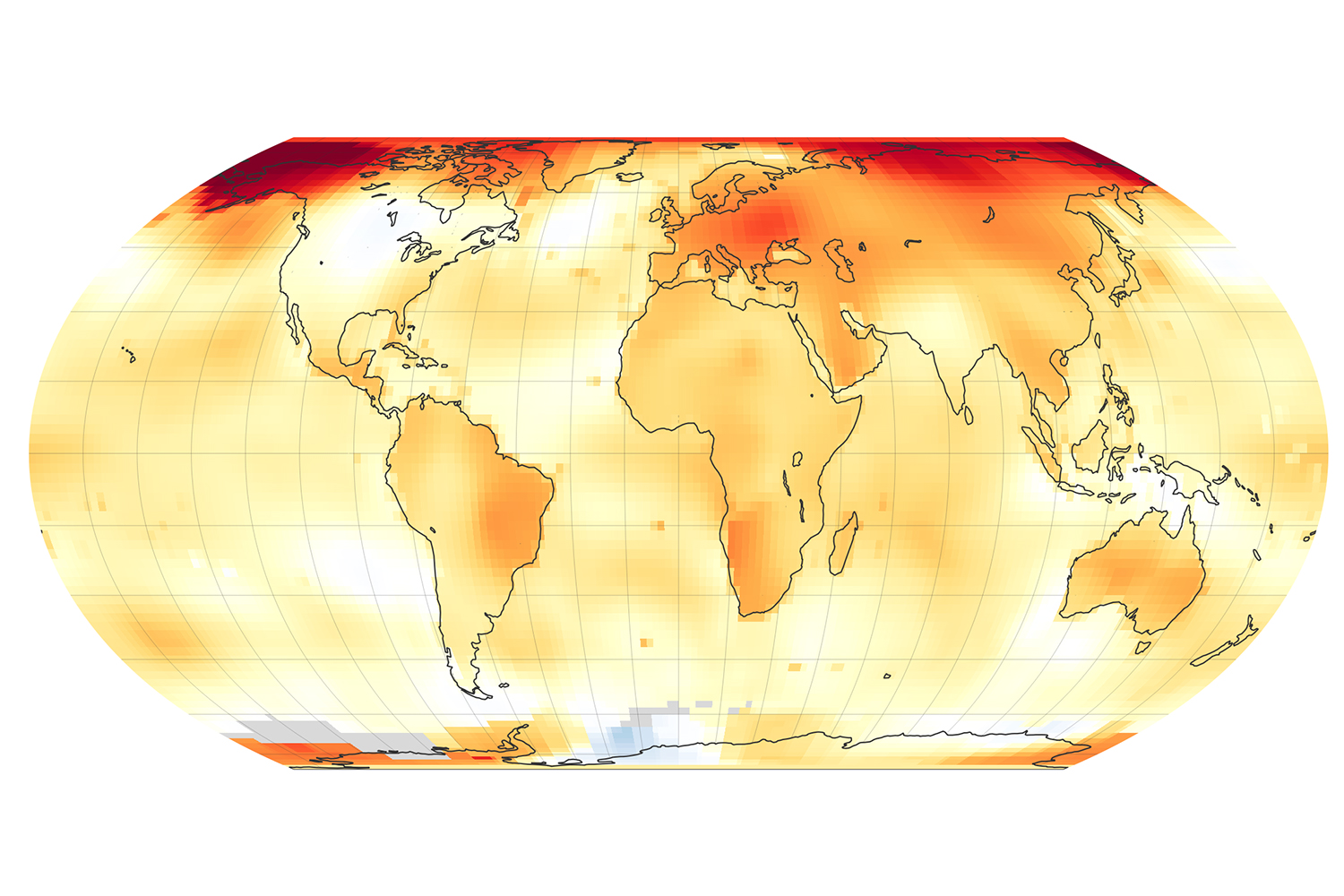

By the end of last year, ecosystems around the world were on fire, and so were many of the old-growth arts institutions that have dominated cultural discourse for years. Recently the wind shifted, and the world was engulfed in a pandemic that has altered life for millions of people. As crisis becomes the mode through which we face the coming months, questions of governance, specifically how money is earned and spent, and ethics, recently framed in terms of ecologies by administrators of nonprofit arts institutions, seem more pressing than ever within an industry that has until now thrived on social closeness, a constant cross-pollination of ideas, and the rapid transaction of currencies.

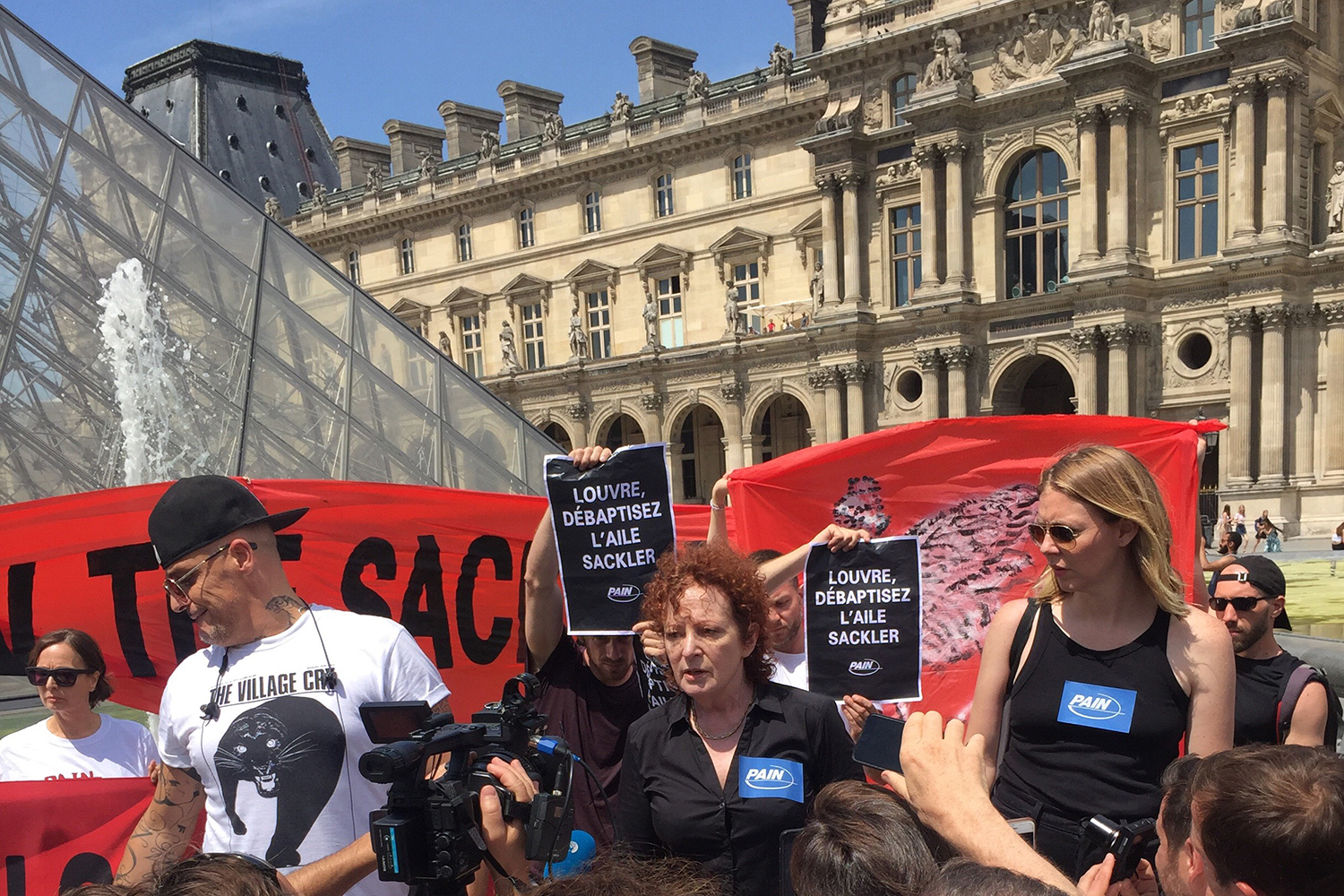

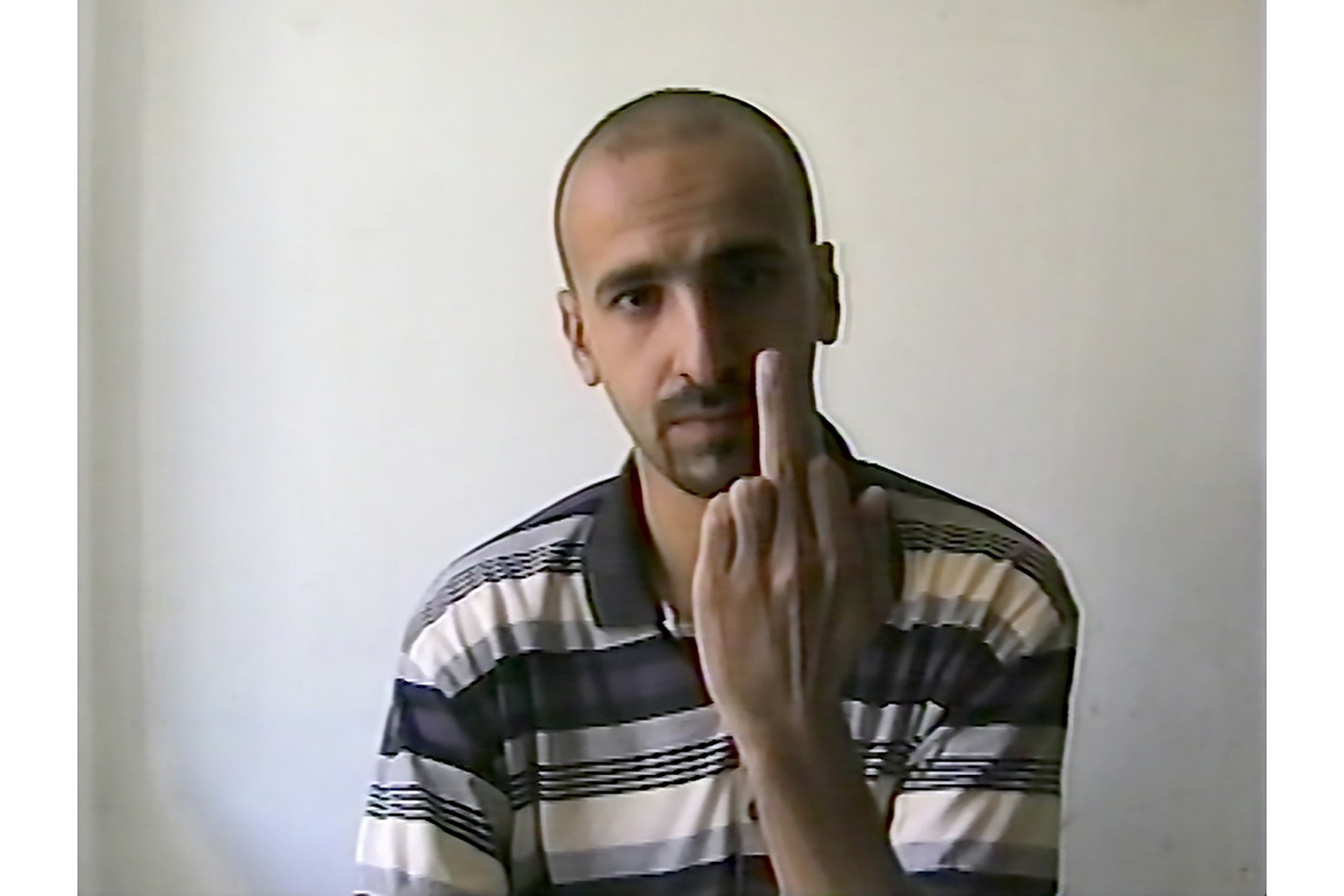

The tipping point was March 2019, when London’s National Gallery and Tate announced they would no longer accept funds from the Sackler dynasty’s opioid wealth. The Metropolitan Museum of Art followed in May and, by June, the CEO of the Serpentine, Yana Peel, had resigned following the disclosure of evidence that her money profits from human rights violations. One month later, Warren Kanders — co-chair of the Whitney Museum’s board and CEO of Safariland, a network of defense equipment manufacturers whose products include body armor and tear gas — did the same. Photographer Nan Goldin led protests against the Sacklers; Kanders made his decision after multiple artists withdrew their work from the Whitney Biennial. In October, British video artist Phil Collins removed his video baghdad screentests (2002) shortly before it was to be exhibited at MoMA PS1 out of solidarity with a prison divestment campaign aimed at Larry Fink, a Museum of Modern Art trustee and CEO of prison-profiteering investor BlackRock. Nearly forty other exhibiting artists signed Collins’s open letter. First as individuals, then in groups, artists ended the 2010s and started the 2020s by challenging big money and the boards that front it for cultural headquarters in New York and London. The effects continue to be felt amidst lockdown, as administrators who had begun to consider how to strengthen the flow of resources to artists must now ensure the future of their institutions.

In January of this year, in a letter cosigned with the choreographer Sarah Michelson, executive artistic director Jenny Schlenzka announced that Performance Space New York was revising its mission statement and handing over its $500,000 production budget and keys to a cohort of artists. Michelson’s new role was described as “ecologist in service” to the group and organization’s staff. Their program, titled 02020, is being determined without creative oversight from Schlenzka, who in her position normally both directs the institution and curates its program. Just over a week later, Hans Ulrich Obrist, artistic director of the Serpentine, which opened its own Sackler Gallery in 2013, authored a text for The Art Newspaper that foregrounded the institution’s commitment to artists as part of a pledge to be environmentally sustainable. Obrist cited lessons already learned from artist friends: recycling clothes thanks to Rose Wylie and flying less with Gustav Metzger in mind. He reminded readers that the institution was the first to appoint a curator dedicated to ecology, Lucia Pietroiusti, and promised that “ecology will be at the heart of everything that we do.” Months earlier, Pietroiusti — who in 2019 curated an opera about climate change for the Lithuanian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale and who in her previous role at the organization had realized live programs around themes of transformation and extinction — expressed her own doubts about reducing ecological work to sound bites, commenting:

I think there is something very dangerous in continuing to say that we all should consume less, because we exist in paradigms that are made for consumption. There is a lot that the individual cannot do at this moment. And there is a tendency…to be product-driven and to present a prototype as a solution. There is usually an object or a building at the end of it.1

Pietroiusti’s cool realism brings Obrist’s pronouncement back to planet Earth and elucidates how semantic invocations like “curator of ecology” or “ecologist in service” can imply so much that they end up meaning nothing. If, as Obrist writes, “[The Serpentine’s] commitment takes in every aspect of the life of the galleries” and will rely on “artists, thinkers, designers, and architects from across the world” to create a new program, then what are the specific models that allow that work to take place rigorously and fairly, and who is responsible for implementing them?

Addressing the root causes of issues as far-reaching as climate change and capitalist inequity, or of slowing the spread of COVID-19, requires power, wielded with explicit goals in mind. But power must move from the top down and bottom up in order to cultivate the coexistence of all organisms, and in the present era of ecological collapse and technological acceleration, up and down no longer feel like reliable directives. If a person with a YouTube channel can be more important — better paid and boasting a larger audience — than the brand they represent, then an artist can be more important than their institutional host. Reintroducing Performance Space New York or the Serpentine as ecosystems in which the most fundamental and endangered organism is the artist has allowed Obrist, Pietroiusti, and Schlenzka to differentiate their institutions to board members, artists, and audiences alike in a crowded cultural landscape. Popularizing the term “ecology” also stresses the weight the institutions seek to place on their relationships to their own and the broader environment. As Pietroiusti has said,

For me, an institution that works in a very embedded way, that thinks about the land it is sitting on, is an ecological institution. I hope that institutions become less hierarchical, more collaborative, and inter-organizational — those are forms of environmental thinking.2

By emphasizing a reliance on artists alongside a redistribution of power, these curators are employing ecology to reintroduce plurality into a system that makes institutions into brands and artists into spokespeople. By turning to artists not just for ideas but for structures and strategies, they are attempting to deviate from the narrow role of art as product and institution as platform that canonical venues like MoMA, where Schlenzka previously worked, have historically upheld.

The risks of using ecology as a metaphor include that it perpetuates these institutions’ ability to profit from more free or freelance creative labor, burdening artists with the task of not only making art, but producing and packaging it to the highest ethical standard. One way to mitigate this risk, outlined in a recent announcement from Performance Space New York, is to remunerate artists for their expanded responsibilities. This proposal is more tested now than when their letter was first published, as arts institutions have closed indefinitely, sending freelance, part-, and full-time employees scrambling for pay. The question that presently emerges is whether institutions can maintain high-minded environmental thinking as their budgets are slashed by cancelled galas and their endowments shrink as markets drop. Amid constant flux, ecosystems around the world are continually rebalancing themselves in order to not destroy the very things that sustain them. So what are the vital things that sustain the arts ecology as we know it, and which of them will survive the present reckoning?

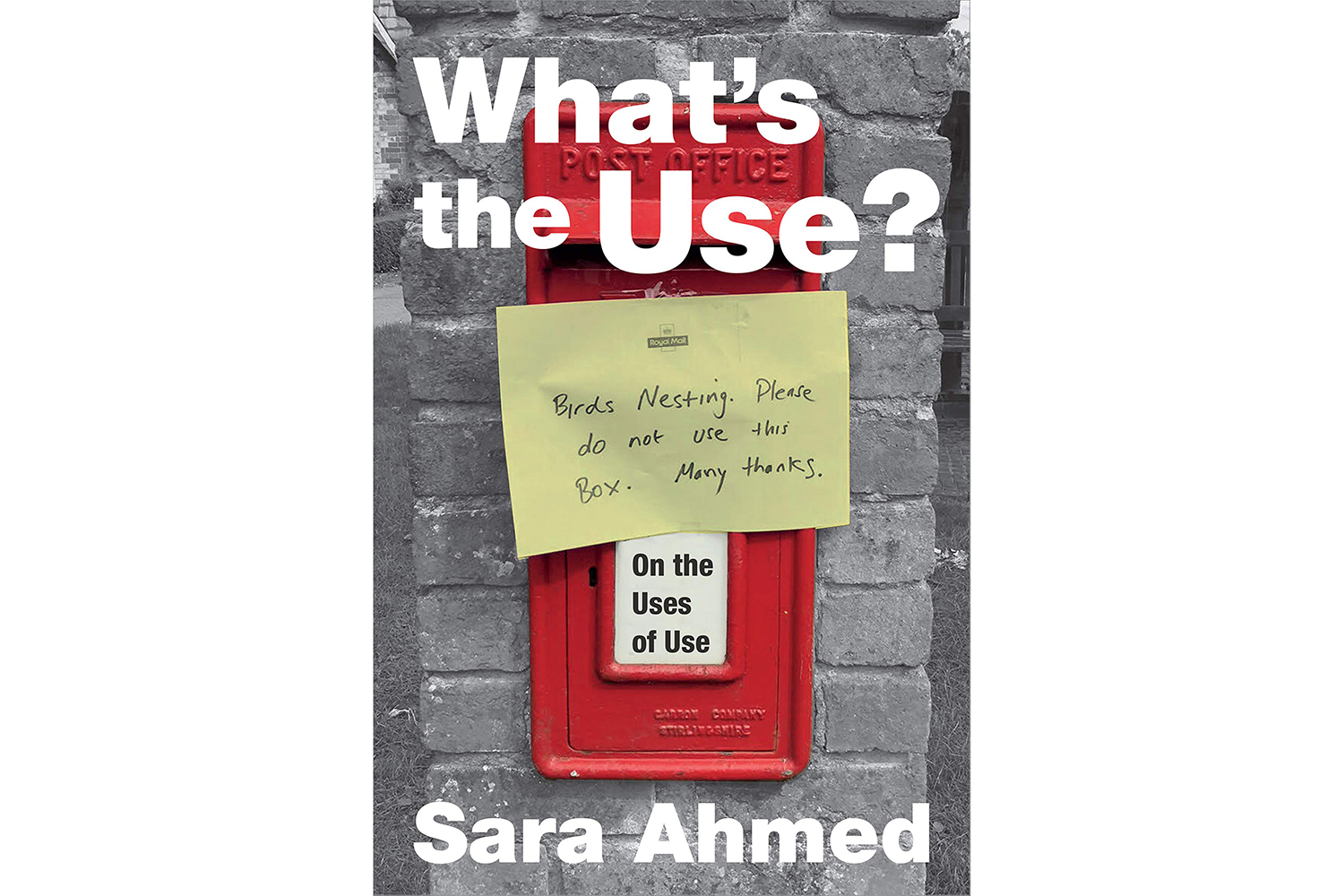

Writing about her work to diversify institutions, Sara Ahmed notes that if one witnesses the movement, they might miss the mechanism. Ahmed’s call to queer the ways through which institutional change takes place reveals how the ease with which ecology as a term circulates might be why ecological action — working collaboratively and inter-organizationally, thinking systemically rather than in terms of spectacle, even becoming carbon neutral — is so challenging. It’s because it’s easy to imagine what Obrist, Pietroiusti, and Schlenzka mean that we need to closely observe the people they engage in their galleries and boardrooms, as well as those they exclude. If these and other leaders are currently forced to cancel programs and furlough portions of their staff, are they still earning what they did in 2019?

Ahmed also observes that creating evidence of doing something is not the same as doing it. The growing prevalence of ecological frameworks has intersected with an equally overdue push to diversify arts institutions. In the Venn diagram of inclusion and ecology, visitors to places like the Serpentine or Performance Space New York emerge as key contributors to shared, biospheric goals of justice and sustainability that can begin to manifest in simple changes. Both institutions have begun to encourage members of the public to get in touch if they are interested in attending programs that they are unable to afford. Although this is a minor change in light of the divestment called for by protestors of Yana Peel last year, this actionable step toward lowering barriers to entry reveals stronger channels for resources and ideas that support institutional adaptation. At present, life in a world shaped by COVID-19 presents unprecedented questions about how individuals participate in society. As arts institutions race to bring their programs online and reach audiences digitally, the precarity of all environments — natural, lived, and built — has rarely been more palpable.

One optimistic next step is that the people chosen to embody ecologies at arts institutions might transcend the conditions — their being situated in an institution — that originally brought them together. As venues remain closed, the artists and audiences who animate them face new pressures and new opportunities to rethink how institutions serve them. If behavioral change leads, structural and formal change can occur. As Ahmed points out, once form is acquired, less effort is needed for an organism to survive within a given environment. In this way, the trend of giving keys, budgets, and power to artists rather than to millionaires could become the new norm that changes institutions as forms. Perhaps one might then consider the ecological turn towards environmental thinking as a controlled burn: the intentional setting fire to a system already in danger of combusting. Perhaps the smoke we see is not a sign of danger as much as evidence of renewal.