A commission for Performa 19, Yvonne Rainer resuscitated and wholly reimagined parts of Parts of Some Sextets, which first premiered in March 1965 (and was never performed since), in collaboration with dancer, choreographer, and pedagogue Emily Coates. The reimagining grew, in part, out of a lack of visual documentation, save for partial notations on graph paper, yet the present version retains its grain and pervasive attitude of on-stage investigation. Guided by cues enfolded in Rainer’s thirty-year-old reel-to-reel vocal recording of entries from eighteenth-century minister William Bentley’s diary, dancers move themselves, with alternating fluidity and glitch, through sequences of activities in choral and solo configurations: hoisting twelve mattresses in and out of stacks, animating thick ship ropes, and playing at swooping avian gesture. Though not on stage in this version, fresh recordings of Rainer’s voice today, interwoven around the original soundtrack, speak in substitute — a “radical juxtaposition”¹ that imbues the piece, some fifty-four years later, with radical contiguity.

EMG: Can you unfold the relation between dance and orality in Parts of Some Sextets?

YR: For most of my career I’ve been interested in putting at least two things together that don’t seem to have anything to do each other, in some kind of radical juxtaposition.[1] I can’t remember exactly what came first: the idea for mattresses or reading a review of this minister’s diary from eighteenth-century Salem. Anyway, I’d spent a couple of weeks in the New York Public Library excerpting sections from this diary that ultimately ran about thirty volumes: he had a long tenure there, into the next century. It’s only since the reconstruction that I’ve been able to see more correspondences between what the audience hears and what they see. I see the analogy between the life in this town and this life on the stage. There’s not much presentation for an audience; it’s like people going about their business with objects and daily life. I realized that there were much more specific correspondences as we went along. You can’t take in both at the same time: your attention ebbs and flows, like what you’re seeing and what you’re hearing. That didn’t bother me, because it was to be two separate things that occasionally came together — or you could ignore one or the other depending on what your interest was. The original performance got a very bad review by Jill Johnston in the Village Voice. She couldn’t follow the soundtrack, and she was bored by the repetitions in what she was seeing. It’s been very gratifying to me that the present audiences seem to be ready for it.

EMG: The piece is highly auditory in that dancers have to double as listeners for movement cues. Does your recording of William Bentley’s text drive performers’ movements?

YR: Yes, in a very mechanistic way: not for content, but for reason to change what is going on on the stage. They’re listening for cues; they don’t necessarily follow everything they hear, but they’re listening for their next phrase every thirty seconds, when they have a cue.

EMG: What were your perceptions upon hearing the recording of your thirty-year-old voice, when the reel was rediscovered?

YR: That was very interesting. For one thing, I’d totally forgotten that I sang this ditty in the middle of it. We brought the recording to the rehearsal, and all of a sudden, this sound comes up! There’s a totally different quality; I kept that. I could have integrated them more with the technician, but I decided to keep that difference in sound quality.

EMG: Although you aren’t a performer on stage in the reconstruction, you remain present as a performer via recorded voiceover.

YR: In the reconstruction, I’m outside of it, and I made a lot of tweaks. Since about a third of the score is missing, the end is totally different. I have no memory of how it ended. There’s one essay from that period that sort of gives a general idea, but I had to make it up all over again. But otherwise, two-thirds of it is pretty exact. Some of the descriptions of the activities I had to reconstruct, like “corridor solo” — I remembered the beginning phrase, and that was all. There was no visual documentation of the dance, so I only had this score on graph paper to go by. There are some much more recent bits of choreography that I inserted. It’s quite a different piece, but I can’t say whether it’s better or worse; or whether these changes make it more agreeable to the present-day audience.

EMG: Is there a benefit to having a dearth of documentation?

YR: Sure. I document everything now that I do, but the first decade of my work, we — and I wasn’t the only one — weren’t thinking like that. Saving for posterity. We were engaged in the nowness of what we were doing, and the excitement of all these ideas ricocheting off of [John] Cage, [Merce] Cunningham, Happenings… It was right in the middle of that ferment.

EMG: You were experimenting with alternative modalities of transmission then as well, such as with Trio A (1966), where anybody who performs the solo can teach it to anybody else.

YR: Yes, Trio A was made in the year after Parts. I didn’t document Trio A until the late ’60s, when I was beginning to turn to film. The first ten years of my choreography is missing as far as film or video go.

EMG: You’ve articulated that your interest in “ordinary movement” came from Cage’s engagement with “everyday sounds,” at least in part.

YR: Yes. Robert Dunn, who was a musician and an acolyte of Cage, gave a workshop and opened up all these possibilities. I remember people going to the windows and looking out on the street as though they’d never seen what people in the street do! That was a whole open field waiting to be mined. Steve Paxton and I used to joke — I’m sure you’ve read this — he claimed to have invented walking, and I invented running. We both made dances based on those activities. But I always liked this idea of radical juxtaposition, like my running dance [We Shall Run (1963)] had this over-the-top explosive requiem of Berlioz, in contrast to the somewhat monotonous trodding around of twelve performers.

EMG: You had visual artists in your original cast, as well as in this iteration. How did that inflect the process of composition?

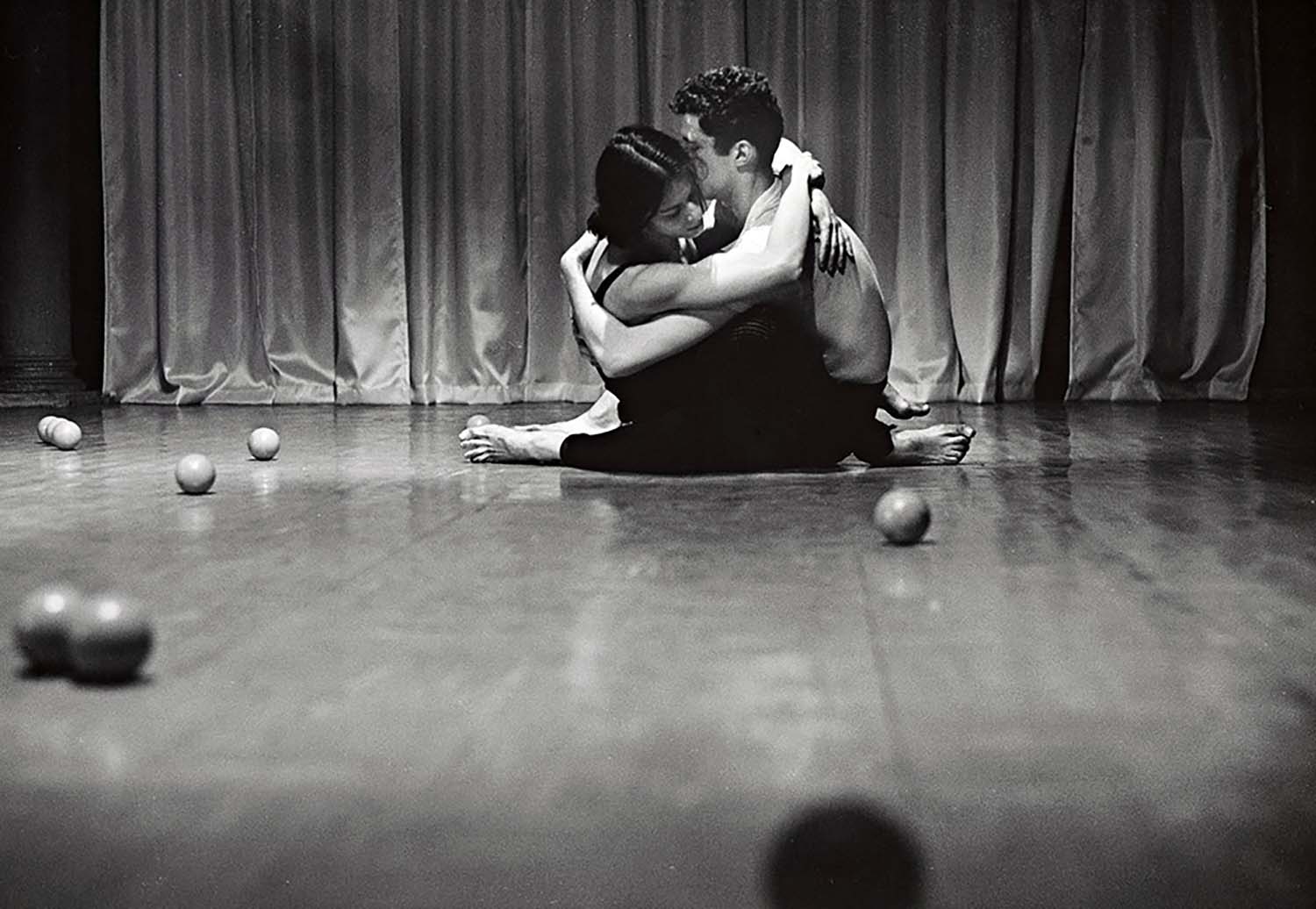

YR: Yes, Liz Magic Laser, Nick Mauss, and David Thomson were in this one, and Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Morris in the original. Morris did some dancerly things. Rauschenberg mainly moved mattresses, and he had a duet with Sally Gross, which required lifting. I gave Rauschenberg to David Thomson! David’s a trained dancer, and I began to see that there was a lot of sitting around and moving mattresses, so I told him, come on, learn this so-called “corridor solo.” I gave him some dancerly things to do according to his talents. I mixed it up. I like the ebb and flow of it. Sometimes hardly anything is happening, or toward the end, people sit and watch tableaux downstage left. Even before the tableaux, people do a thirty-second lift, and they talk to each other. You see constant interactions of pedestrian activity and technically demanding activity.

EMG: Why is it harder to do nothing?

YR: First of all, doing nothing is a misnomer, even when two people are watching you. If you give that assignment to someone, what will they do? They’ll stand around; they’ll twitch. If you’re a choreographer, you set the limits of what that activity is. I was working on three different dances for three different groups of people in the last six months, and one of them was with a group of nine women at Barnard College. I raid my icebox constantly, so they do Chair-Pillow (1969) at the end. I noticed that one of the performers in the back yawned. I caught her at it, and I said, ok, that’s great, just do it a little further along in the second chorus. There are all kinds of pedestrian activity: the context tells you what is permissible and what is beyond the limits. It’s a choreographic process and challenge.

EMG: Your movement cues for Parts — sitting, running, race walk, etc. — made me wonder whether, in the 1960s, you were interested in the space walk.

YR: Not as choreography. I get my ideas from all over, but that hasn’t been one area of investigation. From the very beginning, one critic had said of me, she walks as though she’s in the street, and I haven’t really explored other gravitational contexts.

EMG: You once wrote, “Dance is hard to see.”

YR: Yes. You turn it around, and you don’t always face the same configuration in the same perspective. There was an early solo, called The Bells (1961), in which I did the same movements but kept changing my facing. It’s like walking around a piece of sculpture, and that was an influence.